it looks good on paper - Social Assessment, LLC

advertisement

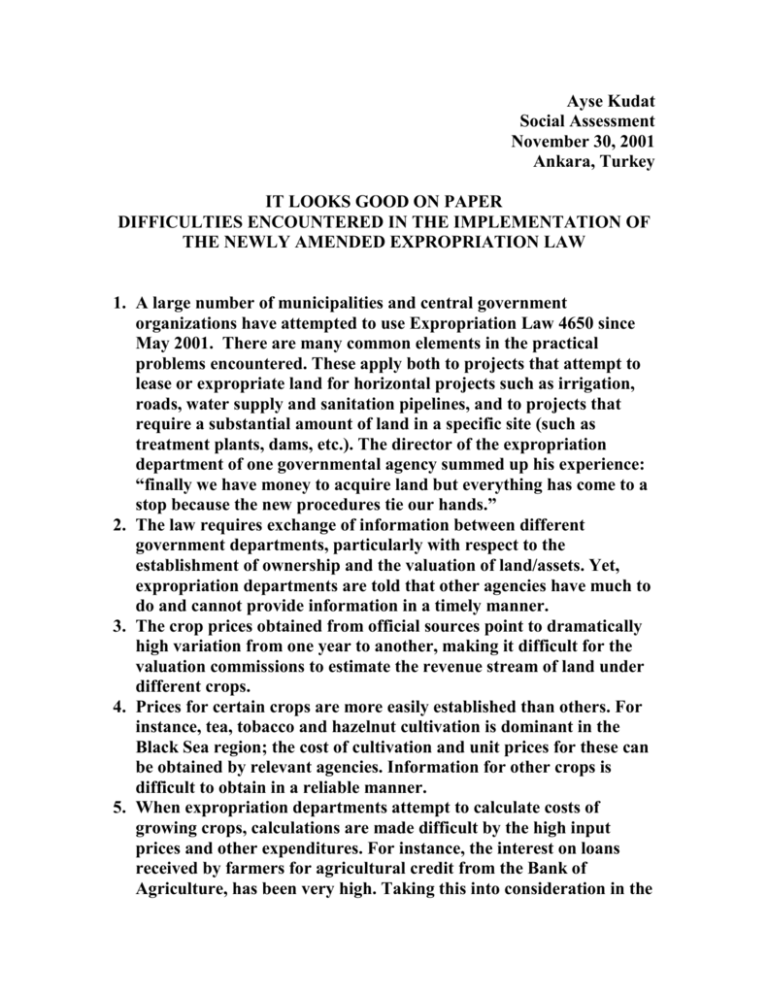

Ayse Kudat Social Assessment November 30, 2001 Ankara, Turkey IT LOOKS GOOD ON PAPER DIFFICULTIES ENCOUNTERED IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NEWLY AMENDED EXPROPRIATION LAW 1. A large number of municipalities and central government organizations have attempted to use Expropriation Law 4650 since May 2001. There are many common elements in the practical problems encountered. These apply both to projects that attempt to lease or expropriate land for horizontal projects such as irrigation, roads, water supply and sanitation pipelines, and to projects that require a substantial amount of land in a specific site (such as treatment plants, dams, etc.). The director of the expropriation department of one governmental agency summed up his experience: “finally we have money to acquire land but everything has come to a stop because the new procedures tie our hands.” 2. The law requires exchange of information between different government departments, particularly with respect to the establishment of ownership and the valuation of land/assets. Yet, expropriation departments are told that other agencies have much to do and cannot provide information in a timely manner. 3. The crop prices obtained from official sources point to dramatically high variation from one year to another, making it difficult for the valuation commissions to estimate the revenue stream of land under different crops. 4. Prices for certain crops are more easily established than others. For instance, tea, tobacco and hazelnut cultivation is dominant in the Black Sea region; the cost of cultivation and unit prices for these can be obtained by relevant agencies. Information for other crops is difficult to obtain in a reliable manner. 5. When expropriation departments attempt to calculate costs of growing crops, calculations are made difficult by the high input prices and other expenditures. For instance, the interest on loans received by farmers for agricultural credit from the Bank of Agriculture, has been very high. Taking this into consideration in the 2 estimation on the net income from land produces high values and pushes the expropriation or lease prices unrealistically high. 6. The valuation commissions established by the expropriation agencies are not subject to the same pressure as the local valuation commissions that operated in the past. Under the new Law, the agency commissions are required to devote more attention to reaching a “scientific” valuation figure. These figures are often far below the figures established by the local level commissions in the past. Therefore, owners/users are reluctant to agree on the new prices offered by the expropriation departments. 7. The valuation of tress also presents a major problem. In some regions (e.g., Black Sea), trees are planted among crops and orchards are rare. In the southern regions, on the other hand, orange or lemon tree orchards are dominant. Expropriation department face major problems and are challenged by the owners in the valuation of individual trees. Moreover, large sub-regional differences in this respect further complicate issues. 8. The law requires that individual plots are visited and the valuation records are created in the presence of owners whose signatures are on these records. However, meeting owners during plot visits is difficult. When owners are invited for negotiations, they often challenge the accuracy of these records and refuse to sign them. The members of negotiation commissions report losing excessive time in trying to convince owners to review and sign these records. There are many instances where they fail to do so. 9. Because there is no requirement to send a “registered letter with confirmation” (iadeli taahhutlu), the expropriation agencies cannot establish whether the owners have indeed received the registered letters of “invitation to negotiation”. Expropriation departments recommend that the letters be sent with a request for confirmation of receipt. They also recommend that for resident owners the field officers of the agency personally deliver the letters. Needless to say, this increases the cost of land acquisition especially for linear projects acquiring small plots of land from large numbers of owners/users. 10.Regardless of the extent of effort, the difficulties encountered in establishing the addresses of absentee owners are many. Often, the friends and relatives of absentee owners provide telephone numbers. Many of these also turn out to be incorrect; in other cases, contacting an owner by telephone during working hours is difficult. 3 11. Many owners who are said to be dead by members of a community still appear as the only owner on the deeds. 12. Application to the local Birth Registration Offices to establish the names and addresses of the heirs of a deceased owner also produces additional deceased names. The determination of living heirs also creates problems. The share of each heir cannot easily be determined. The participation of all the heirs in negotiations cannot always be secured. Also, the heirs fail to bring along a certification of the inheritance to negotiation, thus further complicating and delaying the acquisition process. To underestimate the time and effort required to resolve the acquisition of plots with incomplete inheritance status would be a major mistake. 13. The heirs of a small plot of land to be acquired rarely have much motivation to complete the inheritance procedures. They are also reluctant to pay the taxes and registration fees involved in assuming ownership of their land. In linear projects, the expected compensation to be received by each heir falls short of the time and expenses required for inheritance registration. For this reason, the heirs also refuse to attend negotiations. For the BTC project, this could be a major concern. Failure to register inheritance usually occurs in economically poorer but socially better integrated communities/regions. 14.The land registry system contains large errors. This situation surfaces at the time of the acquisition of the land and the transfer of the title deed. To make the required deed corrections thereafter also causes loss of time. 15.For owners whose addresses cannot be identified, the support of local administration should be sought as per law of communication (#7201, Tebligat Kanunu). Often, it is difficult to obtain their cooperation and even when they cooperate, they cannot always produce the desired results. 16.The negotiation commission does not have sufficient latitude to operate and cannot always match the prices determined by the local commissions during previous years. 17. For linear projects, there is every reason for the expropriation agency to reach a negotiated solution. The cost of legal procedures to be followed for non-negotiated situations is high and the time requirements far exceed those specified by the Law. 18.When the expropriation agencies are forced to seek non-negotiated solutions through the courts, they are faced with overcrowded local 4 courts managed by a single judge. This delays decisions for large numbers of small plots. 19.Because the capacity of local law institutions far exceed the lengthy legal requirements to be met in establishing ownership and acceptable valuation, in some regions special courts are being established. This may be secured in anticipation of emerging problems in some of the project affected areas. 20.The agency’s valuation commission is not invited to the courts. Thus, they cannot present their justification and influence the Court’s decision. 21.There is little knowledge of the changes in the Expropriation Law. This is true even for the specialists. There is an urgent need to disseminate the knowledge of the Law, especially among the people so that negotiated agreements can be reached more easily.