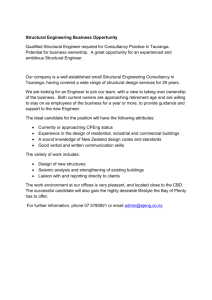

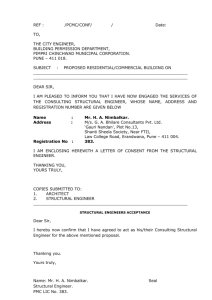

Structural Engineering

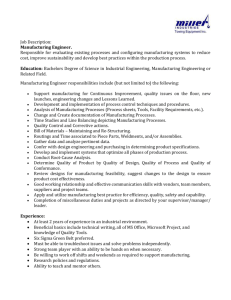

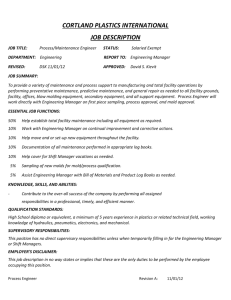

advertisement