TELECOM ITALIA: - Fondazione Rosselli

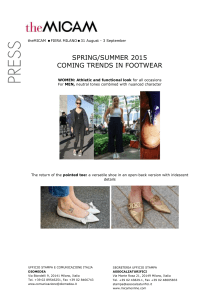

advertisement