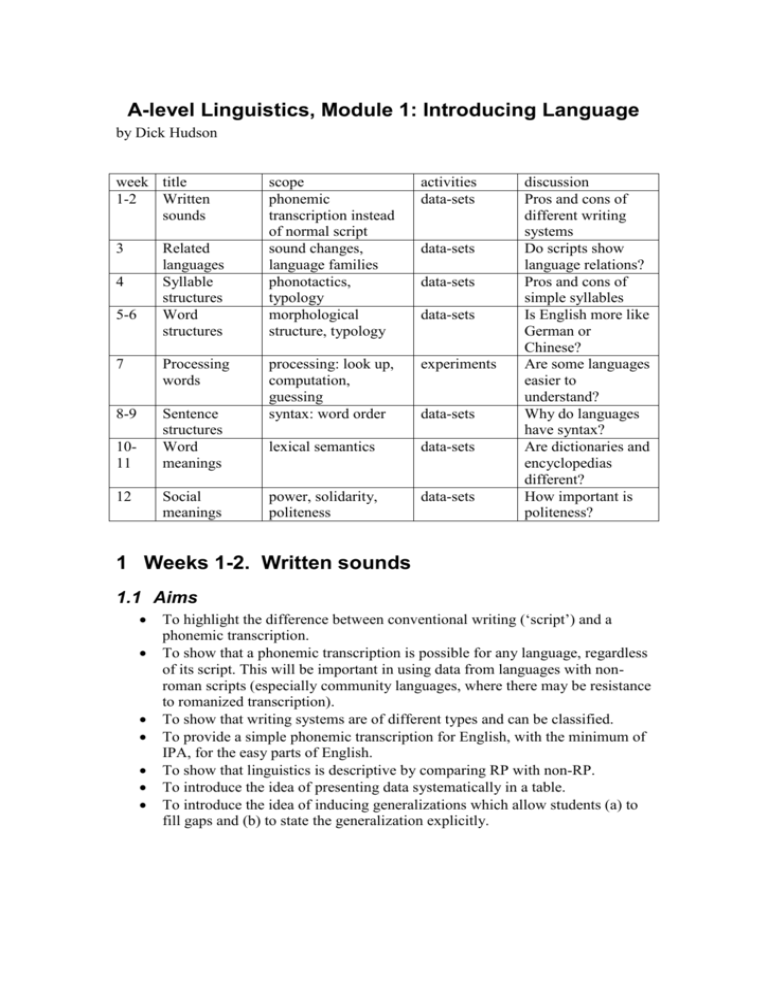

A-level Linguistics, Module 1: Introducing Language

advertisement

A-level Linguistics, Module 1: Introducing Language by Dick Hudson week title 1-2 Written sounds 3 Related languages Syllable structures Word structures 4 5-6 7 Processing words 8-9 Sentence structures Word meanings 1011 12 Social meanings scope phonemic transcription instead of normal script sound changes, language families phonotactics, typology morphological structure, typology activities data-sets processing: look up, computation, guessing syntax: word order experiments lexical semantics data-sets power, solidarity, politeness data-sets data-sets data-sets data-sets data-sets discussion Pros and cons of different writing systems Do scripts show language relations? Pros and cons of simple syllables Is English more like German or Chinese? Are some languages easier to understand? Why do languages have syntax? Are dictionaries and encyclopedias different? How important is politeness? 1 Weeks 1-2. Written sounds 1.1 Aims To highlight the difference between conventional writing (‘script’) and a phonemic transcription. To show that a phonemic transcription is possible for any language, regardless of its script. This will be important in using data from languages with nonroman scripts (especially community languages, where there may be resistance to romanized transcription). To show that writing systems are of different types and can be classified. To provide a simple phonemic transcription for English, with the minimum of IPA, for the easy parts of English. To show that linguistics is descriptive by comparing RP with non-RP. To introduce the idea of presenting data systematically in a table. To introduce the idea of inducing generalizations which allow students (a) to fill gaps and (b) to state the generalization explicitly. 1.2 Activities Data-sets, each consisting of a table with filled cells to show the pattern, and gaps to test understanding. The student’s task is: to fill the gaps then write up the ‘results’ by completing the partial generalizations that emerge from the table. See below for an example. Languages used: N/S English (below), Egyptian hieroglyphs (pictograms > syllabic) French (irregular foreign) Spanish (regular foreign) Gujerati (syllabic) Chinese (idiographic) Invite students to provide data-sets from other languages for presentation to this class and for you to use with future classes. script phonemic south kat gra:s pa:s ? cat grass ? path north kat gras ? paθ 1.3 Discussion What are the pros and cons of different writing systems, including phonemic transcription? 2 Week 3. Related languages 2.1 Aims This unit, exceptionally, takes a historical rather than typological approach to language comparison. It is needed because: o historical and typological comparisons are easily confused o historical comparison is inherently interesting o it provides a useful link to other languages that students know or are studying o there’s a great deal of accessible material on language history. To build on the idea of presenting data from languages with different scripts in phonemic form. To introduce the idea of language families and let students explore the history of languages they know about. To introduce the idea of phonemic change, with more practice in inducing generalizations. 2.2 Activities Data-sets with the number-words ‘one’ through ‘ten’ for a dozen languages, some Indo-European and others not, all presented in phonemic (and script where this is roman). Include Modern and Old English, and Latin and a couple of Romance languages, but (at first) don’t name the languages. The students pick out the ones that look similar (e.g. with /n/ in the word for 1), and note apparently anomalous words (e.g. /faiv/ in Eng and /sãk/ in French). Name the languages. Invite students to contribute further languages. Data-sets from English and French showing regular historical loss of consonants in words like knee, farm and petit. Each set pairs script and phonemic, and includes gaps and a generalization about each sound change to be completed. Maybe include other languages whose scripts reveal recent changes. Back to the number-words: induce some sound changes between Latin and the Romance languages and between Old and Modern English. More data-sets for these languages showing other words affected by the same sound changes, with gaps for students to fill. 2.3 discussion Show a family tree for the Indo-European languages and find the I-E languages in the numbers data-set. Does the tree reflect their relative similarity in number-words? How well does the family tree relate to (1) geography? (2) script? Why might the relations be complicated? 3 Week 4. Syllable structures 3.1 Aims To continue the exploration of sound structure. To introduce the idea of function – that languages have evolved to facilitate communication, which constrains their structures. To introduce the idea of structure – an abstract pattern that holds together smaller parts. To introduce the idea that particular areas of language can be graded for complexity and that simplicity in one area may be balanced by complexity in another. To introduce the method of extrapolating from representative data. To introduce the bracket notation for optionality. 3.2 Activities Data-sets of monosyllables illustrating extremes (shortest and longest) of syllable structure in different languages; o each word shown with phonemes and syllable structure (C,V) as well as script and meaning; o words presented in random order, so students may want to reorder them from simplest to most complex; o languages to include e.g. English (e.g. London), Samoan (or some other very regular (C)V language), German, Russian (or some other complex C...V language) o students complete gaps in syllable structure. o students complete a statement of possible syllable structure. o students use phonemes in known words to invent possible words for each language (and try to pronounce them). o assuming (say) 5 vowels and 10 consonants, students calculate the number of possible syllables per language. Invite students to provide data-sets from other languages for presentation to this class and for you to use with future classes. 3.3 Discussion What are the pros and cons of simple syllables in terms of expressive power (how many words can be distinguished)? Are complex syllables harder to say (or hear) than simple ones? How complex are English syllables compared with other languages? Is a language that has simple syllables a simple language? 4 Weeks 5-6. Word structure 4.1 Aims To introduce morphological structure and morphs. To introduce morphological typology. To continue exploring the interactions between structure and function. To introduce the standard format for inflectional paradigms. To introduce the method of extracting generalizations across rows and columns of a table. To raise the question of how to reconcile generalizations with exceptions. 4.2 Activities Data-sets 1: tables showing 2 inflections for each of 2 lexemes from English: o include a gap in each table to be filled by students. o ask students to divide the words into morphs. o let student complete a generalization in terms of roots and suffixes. Data-sets 2: regular person/number verb paradigms: o for various languages: Spanish/French Arabic Turkish English Chinese o Use phonemes, not script. o Give meaning for each row and column, not for each form. o Add a blank at the end of each row and column, which students fill with any shared morph (ignoring minor allomorphy). o Students complete generalizations about roots and affixes for: each row and column possible words (e.g. ‘word = root (suffix) (suffix)) Invite students to provide data-sets from other languages for presentation to this class and for you to use with future classes. 4.3 Discussion Does simple morphology mean simple grammar (or simple language)? What are the functional pros and cons of complex morphology? Do these generalizations have exceptions? If so, do they matter? 5 Week 7. Processing words 5.1 Aims This is another departure from the typological approach of other units. It is needed because: o ease of processing is an important component in any functional approach to explaining typological trends o it provides a bridge to psychology (for students studying this) and to psycholinguistics, which is an important part of linguistics o it is inherently interesting o it introduces a different set of methods. To continue to think about morphological structure. To encourage students to think of language as a tool for communication and the implications of this for language structure. To introduce the idea that ‘rules’ are generalizations in the mind of a native speaker. To show that we understand in a global way, so we can tolerate considerable local ambiguity. To introduce simple experimental procedures applied to language. 5.2 Activities Students understand and explain plurals for non-words such as fligs (i.e. the WUGs experiment in reverse). How do they know the answer? Students provide the past tense for a range of verbs including difficult ones such as text, wring, wreak, beware, thrive, and rank them for difficulty; they try to explain the difficulties. Students consider the morphological structure of ambiguous words such as undone and try to relate structures to meanings; then they consider how context removes the ambiguity. Students hear word strings and classify them as grammatical or not; the strings include some garden-path sentences (e.g. The horse raced past the barn fell) which are in fact grammatical. Discuss how these examples show the limits of ambiguity resolution and the strength of first guess. etc. (See John Fields, Language and the Mind, for further ideas.) 5.3 Discussion How efficient is language? Is it a perfect tool? How efficient are we? Are we perfect users? Are there any practical implications for ordinary language users? Why are regularity and generalization important? Why do we tolerate irregularity? 6 Weeks 8-9. Sentence structures 6.1 Aims To continue the typological approach to language structure. To extend it to syntax, and in particular to word order. To explain simple syntactic relations (subject, object) and o provide a simple notation for showing them o apply them to a variety of languages o show the need in some languages to recognize other relations. To encourage students to distinguish syntax from meaning by including cases where they don’t match. To explore the limits of diversity in this area. To introduce two-line translations (‘literal’ i.e. for each morpheme, and ‘free’, i.e. for the whole sentence). To show how to sort data according to abstract structure. 6.2 Activities Data-sets which: illustrate languages of different word-order types, e.g.: o Modern English (SVO) o Old English (SOV?) o German (XV) o Turkish (SOV) o Welsh (VSO) o Greek (free) each consist of an unordered series of short simple sentences each occupying four lines: o the sentence in phonemic or roman o a literal translation o a free translation o a structure showing S, V and O. include some gaps in the four lines for students to fill. include a partial generalization about the language’s word order, to be completed by the students. include sentences with meanings such as ‘have’ or ‘like’ which allow different syntactic linkage in different languages, so students must work out for themselves how to recognize S and O in each language on the basis of more straightforward sentences. Invite students to provide data-sets from other languages for presentation to this class and for you to use with future classes. 6.3 Discussion What is the function of syntax? Are some orders easier than others for the speaker or listener? Are there any orders which aren’t illustrated by the sample languages? How does modern English compare with other languages? 7 Weeks 10-11. Word meanings 7.1 Aims To develop the functional focus of typology by considering what ‘meaning’ is. To focus on lexical semantics because this is easier to compare across languages than compositional semantics is. To explore some of the diversity of languages in this area. To introduce ways of thinking and talking about word meaning in terms of conditions of use and perspective. To think about some of the limitations of bilingual dictionaries. 7.2 Activities Data-sets which: are mainly from English but which include some other languages, especially MFL or community languages where some students already have some expertise. focus on particular semantic fields, e.g. o kinship o colour o body-parts (e.g. arm, wrist, hand, finger, thumb) o partying (e.g. party, fun, cool) pair words in one column with ‘definitions’ in another, but leave gaps in both columns for students to fill. Students who speak other languages can construct their own data-sets for comparison with English, and present the results to the class. 7.3 Discussion Do different languages reflect different cultures? Is it possible to think ‘outside’ your language and its meanings? Can languages adapt to different cultures? 8 Week 12. Social meanings 8.1 Aims To introduce sociolinguistics. To extend the discussion of function and meaning to include social functions and meanings. To provide a way of thinking and talking about social functions in terms of power, solidarity, face and politeness. To provide a bridge both to other A-level subjects: foreign languages and English language. To provide an opportunity for students to learn usable greetings etc from local community languages. 8.2 Activities Data-sets which: are from different languages, including English, MFLs and community languages. consist of lists of words (or other expressions, such as inflections) which show power and/or solidarity, or which are used for politeness (to protect face), from areas such as: o greetings and farewells o significant-activity markers (e.g. bon appétit! bless you! cheers!) o request formulae (e.g. please, thank you) o names (e.g. Mr Smith, Jonnie) o personal pronouns. allow students to compare the ‘meanings’ expressed in different languages and find differences or gaps. Students could provide small situated corpora (speech, drama) from different languages which they can search for relevant words in order to compare usage in detail. 8.3 Discussion How important is linguistic politeness? Why? How do bilinguals cope with differences between their languages? How important are differences between languages in cross-cultural communication?