323-Keywords

advertisement

Introduction to Word Structure (continued)

1.

grammatical conditioning, lexical conditioning, and suppletion

A.

grammatical conditioning is when the selection of a particular allomorph is

determined by a certain grammatical class--irregular verbs in English.

i.

see, saw, seen determined by the present, tense, past tense, and

the non-progressive participle (these are grammatical features).

B.

lexical conditioning is when an irregular morph is used with a specific

lexical item or a small group of lexical items:

i.

e.g. the noun plural “-en”; it is determined by child, ox, brother (in

the religious sense) (these are lexical items).

B.

There is so little differentiation between grammatal and lexical

conditioning that I won’t hold the class responsible for this. However, I will

hold the class responsible for phonological contioning and lexical

condition redefined.

C.

Lexical condioning: if the form of a grammatical affix is determined by a

special property of a lexical item (irregular form), then the conditioning is

called lexical conditing.

D.

Phonological conditioning. If the conditioning factor is determined by

phonological contexts, then the allomorphic conidition is phonological.

i.

ii.

iii.

B.

ditch, ditches (/ˆz/ is inserted between two sibilants (see 2 below)

cat, cats /s/, /s/ assimilates the a preceding voiceless consonant.

bird, birds /z/, this is the default form (see 2 below).

Suppletion is when two or more allomorphs are not phonologically related.

i.

go, went, gone

2.

Underlying Representations

A.

This topic is very controversial!

B.

Given a set of allomorphs, is there one such allomorph such that all other

can be derived from it?

i.

ii.

B.

“z” -> “s” / [-Voice] ____.

No one really knows.

i.

B.

“z” -> “ˆz” / [+Sibilant] ____.

Some just think they do.

An alternative solution

i.

set theory

(a).

a morpheme is a set of allophones which share a common

set of grammatical features.

(b).

One of these allomorphs is selected by

(i).

(ii).

B.

lexical selection

phonological selection

The prefix {INn e g } is a case-in-point.

i.

ii.

speakers are not normally aware of allophonic variants.

some evidence that the phoneme might be an underlying form which

the subparts are derived.

iii.

But how do speakers of English process this information?

iv.

Really uncertain.

v.

The variations of {IN-} — the rules for these differ from the normal

rules of English.

(a).

in+operative, in+ability, in+controllable, in+grate, in+justice,

in+civility, in+destructible, in+violable, in+tolerable, in+fertile,

in+visible.

(b).

im+material, im+pure,

(c).

il+logical

(d).

ir+regular

(i).

The assimilation pattern is not from English but

borrowed from Latin.

ii.

There may be a default form, but are the allomorphs derived direct

from this form? No!

iii.

These forms may be learned as is, but with an invisible logic that

keeps this stuff straight.

iv.

2.

Initial observation here is to determine the pattern of {IN-}

The Nature of Morphemes.

A.

portmanteau (I): bundle of grammatical features: [+Voice, -Cons].

B.

portmanteau (ii): two or more syntagmatic grammatical morphs pushed

into one morph. Fr: “au” <- “a le”. /ø/ <- /a/ /l´/.

C.

empty or formative morph

i.

B.

must have a function.

zero morph (depending on the theory), perhaps a false notion, perhaps

not.

i.

best dispense with trashing zero morphs and leave the problem for

advanced morphology.

ii.

In set theory, zero morphs are allowable; they are called an

empty set, written {}.(or º).

iii.

This may be the way to go.

_

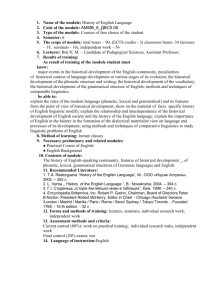

Course Outline 323

Keywords - L323.1

Keywords - L323.3

This page last updated 2 FE 2004