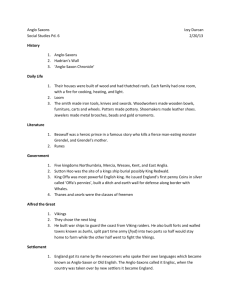

Anglo-Saxons - imaginative

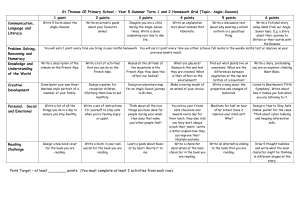

advertisement