Clinical Evaluation - University of Alberta

advertisement

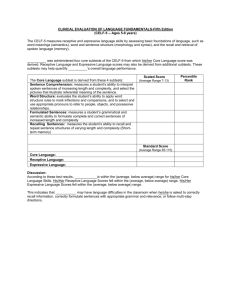

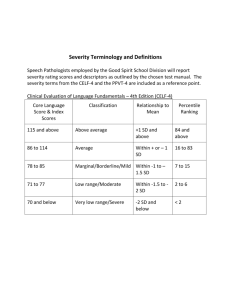

Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Test Review: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-4 (CELF-4) Name of Test: Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-4 (CELF-4) Author(s): Semel, E., Wiig, E., and Secord, W. Publisher/Year (Please provide original copyright as well as dates of revisions): PsychCorp 1980, 1987, 1995, 2003 Forms: Form 1 ages 5-8 years and Form 2 ages 9-21 years Age Range: 5 years, 0 months, to 21 years, 11 months Norming Sample: Preceded by pilot studies examining new and revised subtests as well as bias review, tryout research on testing (including scoring studies) involving 338 SLPs and psychologists and 2, 259 students ages 5 to 21 across the US was conducted. A clinical study focused on 513 students with language-learning disorders. Students in these studies spoke English as their primary language. Bias and content review was conducted by an independent panel of SLPs and education specialists who were “…experienced in test construction and use” (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003, p. 205). The review focused on gender, racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and regional biases. Group performance differences were examined statistically. The Standardization phase engaged 600 examiners in 47 states from four US regions: Northeast, North Central, South, and West in the Spring and Summer of 2002. Students had to be able to take the test in the standard manner and had to use English as their primary language. Percentages of students for whom languages other than English were spoken were identified. Tables and Figures were provided for all combinations of sample characteristics. Total Number: 2 650 Number and Age: 200 students at each age level from 5 years to 17 years, 50 students in each age years from 17 to 21 Location: 47 states in four regions Demographics: age, gender, race/ethnicity, geographic region. Rural/Urban: not specified SES: stratified by four parent education levels: < Grade 11, Grade 12 completion, college, and university Other (Please Specify): “Children receiving special services” constituted 9% of sample with 7% of the sample diagnosed with language disorders; numbers consistent with data from National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities (2003) and US Office of Education Program. The authors note that previously CELF-3 did not include these children in the standardization sample. Summary Prepared By (Name and Date): Eleanor Stewart 12 Jul 07, additions 16 Jul 1 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Test Description/Overview: The test kit consists of the examiner’s manual, two test item booklets, two different record forms, observational rating scale form, and test booklets, and a CD-ROM scoring assistant. The manual is 395 pages long. Theory: The theory upon which this test was developed presents a developmental stages model using milestones identified from extensive research. Comment: Pretty impressive given the age range covered. Four subtests together creating a Core Language Score constitute the first level in which the presence of a language disorder is identified. The four subtests chosen are different for each age group. At subsequent levels the examiner can choose to explore the nature of the disorder, the underlying clinical behaviours, and their impact on the student’s classroom performance. The model is depicted in Figures 1.1 (The CELF-4 Assessment Process Model) and Figure 1.2 (An Alternate Approach To Using The CELF-4 Assessment Process Model). Chapters 2 and 3 are dedicated to extensive description of the first two levels while the remaining levels are presented in Chapter 4. The cluster of subtests appropriate to each level for each of the three age ranges is outlined in Figure 1.3 (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 5). Comment: The test is organized on a four level assessment model of clinical decision-making that would be familiar to clinicians in speech and language. The authors state that important changes to CELF include: Phonological awareness subtest, Memory subtest, and New versions of subtests. Revisions to existing test formats as well as the new additions are described in Chapter 6, “Development and Standardization” (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 199) which details the pilot, tryout, and standardization research phases. Fine print on inside cover acknowledges that “Some material in this work previously appeared in the Children’s Memory Scale …and Wechsler Memory Scale”. 2 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Appendix B (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 305) discusses bias review as well as guidelines in table form from research addressing how culture affects assessment, and dialectal variations in syntax and morphology that are found in the U.S. (e.g., African American, Southern White, Appalachian). Spanish influences on English Phonology and Syntax are also outlined. Particularly interesting is a table on “Alternate Responses to the Word Structure Subtest Items for Speakers of African American English. Comment: Buros reviewer, Vincent Samer, notes: “The CELF-4 manual is careful to point out in Chapter 2 that accommodations for cultural and language diversity will invalidate the norm-referenced scores” (Langlois & Samar, 2005, pp. 222-223). Comment: This poses an important question about children for whom English is a second language and larger numbers of children identified as ESL and more attention to this issue is required. Also further attention to cultural influences (as we are aware of Aboriginal children being over-identified), and low-print, low-talk homes is needed. Purpose of Test: The purpose is to identify, diagnose and monitor language and communication disorders in students age 5 to 21 (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 1). Areas Tested: Subtests are described briefly in Table 1.1. The subtests are: 1. concepts and following directions 2. word structure 3. recalling sentences 4. formulated sentences 5. word classes (1 and 2) 6. sentence structure 7. expressive vocabulary 8. word definitions 9. understanding spoken paragraphs 10. semantic relationships 11. sentence assembly 12. phonological awareness: 17 tasks criterion referenced (meets age or not) 13. rapid automatic naming (RAN): criterion referenced (normal, slower, non-normal for speed and normal, more than normal, and non-normal for number of errors) 3 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 14. word associations: criterion referenced 15. number repetition (1 and 2) 16. familiar sequences (1 and 2) 17. pragmatics profile 18. observational rating scale: in accordance with US education legislation. Phonological awareness includes: detection, identification, blending, segmenting across word, syllables and phonemes. Comment: This is the best description and examples I have seen of phonological awareness. I learned from this. Authors state that results should be interpreted in relation to student characteristics, eg. students with articulation disorders will have problems with specific phonemes or students may have no experience with these types of tasks. A section titled “Clinician’s Notes” assists with additional information about the implications of student performance in relation to reading and spelling. As well, the authors cite the Wolf, Bowers, and Biddle (2000) study on the relationship between Rapid Automatic Naming (RAN) and phonological awareness in which deficits in these constitute “a double deficit” (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 129). In recognition that certain cognitive skills are involved in understanding spoken language, subtests were developed to assess aspects of working memory and executive functioning. The RAN addresses working memory and aspects of sentence assembly. Formulating sentences and word association are cited by the authors as related to executive functioning though executive functioning itself is not tested (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 243). Areas Tested: see also above list Oral Language Vocabulary Grammar Narratives Other (Please Specify) Phonological Awareness Segmenting Blending Elision Rhyming Other (Please Specify) Listening Lexical Syntactic Supralinguistic Who can Administer: Speech-language pathologists, special educators, school psychologists, and “diagnosticians who have been trained and are experienced in administration and interpretation of individually administered, standardized tests” (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 1) may administer this test. Administration Time: The time varies with the number of subtests administered as well as the age of student and other student characteristics. 4 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Test Administration (General and Subtests): There are a total of 18 subtests but not all subtests are administered. This is where the assessment model is useful for selecting from among the subtests. Start points are marked by age and are easy to find. The discontinue rules are clear and allow the test to stop before the student becomes too discouraged. The record form has well identified start points (by age) marked with arrows, times, and discontinue rules with colourful icons. Examiners will need to be careful to read each discontinue rule as they are different for each subtest. Some tests allow repetitions but others do not. Some subtests have up to three trial items; some have no trials. The record form includes the specific instructions for each subtest. Comment: I think that examiners should be familiar with the instructions and not rely solely on the record form. A feature of the CELF-4 is Extension Testing. The authors define extension testing as a systematic procedure for varying the “content, directions, and responses required” (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 16) in order to locate the point at which the student’s ability “begins to break down”. Or conversely, the examiner can find the level of instruction/cueing that the student needs to be successful. The authors suggest that this information can then be compared to classroom and other situations. Extension testing instructions are included in most of the subtest administration instructions within the manual. Each subtest is individually outlined with administration directions, item scoring, subtest scoring, extension testing, as well as specific instructions. At the introduction of each subtest, a table presents the relevant score ages across the composite areas, materials needed, the start point, whether or not repetitions are permitted, the discontinue rule, the objective, and the relationship to curriculum and classroom activities. Very specific information is provided for each subtest. For example, the Understanding Spoken Paragraphs subtest includes information about Priming the Student, a procedure that “provides an auditory map for the student” (p. 83). Subtests are scored objectively with the exception of: the Word Structure, Expressive Vocabulary, Formulated Sentences, Word Definitions, Word Classes 1 and 2, and Word Associations which require “clinical judgment, and qualitative and quantitative judgments about student responses” (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 232). 5 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 6 Appendix A provides detailed examples of responses and corresponding scoring for the Formulated Sentences and Word Association subtests from the standardization sample. Authors acknowledge that examiners will encounter idiosyncratic responses that can be compared to responses provided. Appendices C and D provide scoring conversions to standardized scores. Comment: This is a remarkable test in terms of the detailed instructions. In order to administer accurately and reliably, to make best use, I strongly recommend that examiners practice, practice, practice before using the test in a clinical situation. Some of these tests are totally unfamiliar to me but I understand their intent and want to preserve the integrity of the tasks. Perhaps this is why Wayne Secord’s presentation at Alberta College of Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists (ACSLPA) 2007 Conference was titled, “Know thy CELF”. Test Interpretation: Chapter 3 provides a detailed interpretation of results for assessment levels 1 and 2 (pp. 97-117). The authors state how to derive scaled scores from raw scores as well as how to calculate index scores, standard scores, percentile ranks, and test-age equivalents. Additionally, the authors guide the reader through determining and describing the examinee’s strengths and needs based on test results. Chapter 4 continues with a description of levels 3 and 4 which includes “when to administer subtests to evaluate related clinical behaviors”, “criterion-referenced subtest scores”(phonological awareness, word associations, etc.), authentic and descriptive assessment measures (pragmatic profile and ORS). At the end of Chapter 4, there are 7 case study examples outlined in detail using CELF-4 results. Comment: These two chapters are essential reading for clinicians preparing to convey results of the child’s performance. The chapters are well written and easy to follow. Standardization: Age equivalent scores (by subtest scores) Grade equivalent scores Percentiles Standard scores (and subtest scaled scores) Stanines Normal Curve Equivalents Other (Please Specify) Core Language and Index Scores which are standard scores in Appendix D. Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Criterion-referenced subtest scores (Appendix G) association (age 5-21 yrs.), phonological awareness (age 5-12:11 yrs.), rapid automatic naming in time per second and error (5-21:11 yrs.), and pragmatic profile (5-21:11 yrs.) Reliability: Internal consistency of items: Composite scores yielded high alpha coefficients in the range from .89 to .95. Subtest coefficients were lower, in the range from .70 to .91. Test-retest: 320 students were retested with high correlations on composite scores demonstrated (with .90+ reported for all age groups). Subtest scores were less robust with ranges from .60 to .90. The average interval in days was 16. Inter-rater: Two raters were chosen randomly from a pool of 30 raters who had trained under the supervision of the test developers. Agreement for subtests that required scoring judgments were reported. High agreement was evidenced (.90 to .98). Other (Please Specify): Reliability for clinical groups (405 students in four groups: language disorder, mental retardation, autism, and hearing impairment) was reported. Authors include inclusion criteria and demographic information. SEMs and confidence intervals were provided for 68%, 90%, and 95% levels. Comment: Buros reviewer, Aimee Langlois, makes this statement: “The authors cogently explain possible reasons for these results and provide standard errors of measurement for all subtest and composite scores for each age level. This mitigates the impact of low reliability correlations by helping test users determine how much of a child's score on any subtest varies from his or her potential score. Examiners should therefore interpret results from subtests with low internal consistency by first consulting the standard error of measurement table in the manual and after having read sections of the manual that pertain both to possible reasons for low internal consistency and to score differences” (Langlois & Samar, 2005, p. 219). The information on reliability is very important but I am concerned that it will be missed as most clinicians do not read the information in the manual; except perhaps when we are students and are assigned this as a learning task. The low reliability for particular subtests is a concern. Clinicians should think about how to fairly interpret performance on these subtests and whether or not to simply use the results as “information only”. Validity: Content: Based on the literature review, expert panel review of content, and clinician feedback, the authors provide rationale for the addition of new subtests, added items, and changes to existing subtests. Well-documented language skills and developmental 7 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 8 progression were presented. Criterion Prediction Validity: Authors were able to demonstrate in studies that there are high correlations with CELF-3. Construct Identification Validity: “Response process”, which means that the task is shown to elicit the desired response in a desired way (a direct path), “refers to language and cognitive skills used or behaviors engaged in by examinees to accomplish the tasks presented. These language skills may be directly related to the construct being measured or may be language skills that contribute to the performance of a specific task” (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 242). In this section, the authors explain and review the evidence of skills known to be engaged in during task performance. Among these skills, they identify working memory and executive functioning. While the RAN subtest directly assesses aspects of working memory, executive functioning is not directly assessed. Also, beginning on page 246, there is a very complicated section on Factor Analysis research that was initially completed on CELF-3 and extended in this edition. Structural Equation Confirmatory Models for age groups: 5-7, 8, 9, 10-12, and 13-21 years are provided. Authors state that previous evidence from factor analysis demonstrated a “general language ability” consisting of receptive and expressive dimensions that “cannot be separated from one another in an attempt to conduct independent or unrelated analyses” (Semel, et al., 2003, p. 246). Further, with the CELF-4, the authors wanted to “create and test a theoretical model of language ability that includes both receptive and expressive components (indexes) nested hierarchically within the framework of a Core Language ability composite measure” (p. 246). Comment: The Buros reviewer states, “Comprehensive intercorrelational and factor analytic analyses confirmed the basic construct validity of the instrument. A series of structural equation modeling studies on different age groups, reported in the manual , add new insight into the way different components of language function determine subtest performance at different developmental stages” (Langlois & Samar, 2005, p. 222). Differential Item Functioning: See Buros statement above. Other (Please Specify):Clinical validity studies reported in the manual confirm CELF-4 differentiates clinical populations of children with language disorders, autism, mental retardation, and hearing impairment. However, (see comment below…) Comment from the Buros reviewer: “Performance differentiates language and working memory weaknesses in specific clinical populations. Comparative studies indicate that the CELF-4 is substantially more sensitive to these weaknesses than the CELF-3” (Langlois & Samar, 2005, p. 222). Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell Comment from the Buros reviewer: “A caution is in order regarding the application of the CELF-4 to special populations such as children with hearing losses. The CELF-4 manual is careful to point out in Chapter 2 that accommodations for cultural and language diversity will invalidate the norm-referenced scores. …In any case, the CELF-4 has never been comprehensively validated on children with hearing losses and no norms for that population are available. Great caution should be exercised in attempting to administer and interpret the results of the CELF-4 with children who have hearing losses, especially when the goal of the evaluation is to separate the intricate influences of deafness and other causes of underlying language disabilities, respectively, on language development” (Langlois & Samar, 2005, pp. 222-223). Summary/Conclusions/Observations: *The authors were attentive to the U.S. legislative changes that required testers to address “curricular goals and academic benchmarks” (p.198) thus specifically creating the rationale for the Observational Rating Scale (ORS). *There is less of an appeal for Canadian clinicians who must deal with provincial variations. I wonder how much variation there is given the differences in resources and, perhaps, in working definitions of clinical categories? Is there such information? Clinical/Diagnostic Usefulness: The CELF-4 is intended as a diagnostic tool and it is used by clinicians for exactly that purpose. That the sensitivity has been proven is one of the strengths of this test as clinicians are most concerned about accurately identifying children with language problems particularly when funds are limited as they most often are. I would feel confident making a recommendation for intervention on the basis of CELF-4 results along with my other clinical tools in a battery for diagnostic purposes. The test authors and developers have provided us with a strong tool that can be linked to classroom language performance. The authors actively sought input from clinicians both formally with focus groups and informally through communication received from users. I believe this strategy accounts for its user-friendly appeal. Like most other test manuals, clinicians are likely only to read the pertinent sections to prepare for test administration. At 395 pages, the sheer size of the manual is probably a deterrent for some who might be interested in reviewing aspects of the test beyond what is necessary for administration and interpretation. Not to worry though, since just about every aspect of test development and standardization is provided for the keen reader of test manuals. Like the other well-researched and standardized tests reviewed so far, the CELF manual provides a wealth of information about test psychometrics. 9 Hayward, Stewart, Phillips, Norris, & Lovell 10 I found the figures and tables useful and easy to decipher. The manual was well organized despite its size. I like the outline in each subtest that identifies the relevance of the skill tested to curriculum and classroom activities. I have used this information in communicating to others and in program planning. I appreciate the tutorial on diagnostic accuracy on page 271. This brief explanation is useful in discussing screening expectations especially when there is a “coding for cash” imperative. References Langlois, A., & Samar, V. J. (2005). Review of the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-4. In R.A. Spies, and B.S. Plake, (Eds.), The sixteenth mental measurements yearbook (pp. 217-223). Lincoln, NE: Buros Institute of Mental Measurements. Secord, W. (2007). Know thy CELF. Alberta College of Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists Annual Conference, Edmonton, Alberta, 15 October 2007. Semel, E., Wiig, E. & Secord, W. (2003). Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals -4 (CELF-4). San Antonio, TX: PyschCorp. Wolf, M.Bowers, P. G., & Biddle K. (2000). Naming-speed processes, timing, and reading: A conceptual review. Journal of Learning Disability, 33, 387-407. To cite this document: Hayward, D. V., Stewart, G. E., Phillips, L. M., Norris, S. P., & Lovell, M. A. (2008). Test review: Clinical evaluation of language fundamentals-4 (CELF-4). Language, Phonological Awareness, and Reading Test Directory (pp. 1-10). Edmonton, AB: Canadian Centre for Research on Literacy. Retrieved [insert date] from http://www.uofaweb.ualberta.ca/elementaryed/ccrl.cfm