Language & Culture: Context, Meaning, and Sapir-Whorf

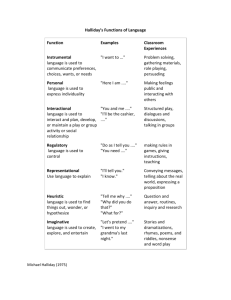

advertisement

Language and culture Context of situation, context of culture Anthropology in the 20th century began to study how culture moulded language or how language was rooted in culture. The terms context of situation and context of culture were coined by Bronislaw Malinowski: language can only be fully understood when these two aspects are understood implicitly or explicitly by the interlocutors. In trying to 'translate' the language used by the Trobriand Islanders, Malinowski felt he add to add a commentary making explicit what was implicit to them, including traditions and beliefs. Malinowski (1949: 207): "Language has a setting… language does not exist apart from culture." If you think of language in terms of meaning then the context of situation is important because the meaning is the response you get, which depends on what surrounds the speech event but also on the experience of the interlocutors. One way of looking at meaning is to say that it is culture bound. Another, from semiotics, is that the meaning of a sign is arbitrarily assigned according to context. Malinowski's ideas were developed in Britain by Firth and later by Halliday. Firth introduced the notion of sociological linguistics as early as 1935: its goal was to describe and classify “typical contexts of situation within the context of culture ...[and]... types of linguistic function in such contexts of situation” (Firth 1935, quoted in Halliday 1973: 27). The framework later developed by Firth included the participants in the situation, their action (both verbal and non-verbal), the effects of the verbal action, and other relevant features. Firth's (1957) key contribution was to assert that all linguistics is the study of meaning and that meaning cannot be divorced from the social context or context of situation. Halliday, like Malinowski, looks at language as behaviour potential, an open-ended set of possibilities: “The context of culture is the environment for the total set of these options, while the context of situation is the environment of any particular selection that is made from within them” (Halliday 1973: 49). The translator, as a mediator between cultures, has to select, from among all the potential meanings available, the one that is appropriate to the actual situation he or she is dealing with at that particular juncture. The focus of Halliday's approach is on what people actually say: language is a network of options that are assigned functions when the language is used in a context and the main evaluative criterion is not grammaticality but markedness Markedness: the more obligatory an element is, the weaker is its meaning, while the more unexpected a choice, the more marked it is and the more meaning it carries. However, the more marked a choice is, the greater is the need for it to be contextually motivated in some way. Of course, all languages can convey anything in one way or another – some require more words than others and may have to resort to paraphrase. Jakobson (1959): "Languages differ in what they must convey and not in what they can convey." Sapir-Whorf hypothesis "That the world is my world, shows itself in the fact that the limits of that language (the language I understand) means the limits of my world." (Wittgenstein 1921) Strong version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis: that language determines what we think. Largely rejected today – language and thought are not the same thing. Weak version: that language influences thought, it is one factor that influences how we understand reality, but it does not determine it. Halliday (1992: 65): "grammar creates the potential within which we act and enact our being. This potential is at once both enabling and constraining: that is, grammar makes meaning possible and also sets limits on what can be meant." Our perceptions are always mediated by our assumptions and beliefs, and by the language we speak. Colours: the spectrum divided differently by different languages. Several language have no separate words for ‘blue’ and ‘green’, some don’t distinguish between green and yellow. All languages seem to have black, white, red, but green/blue/brown/yellow varies. e.g. Sioux Indians same word for green and blue. e.g. Nias, Sumatra: black, white, red, yellow, while green/blue/violet all called ‘black’ Languages have different notions of relationships, e.g. brother, cousin, uncle, aunt etc. Guugu Yimithirr (Australia) no words for left and right, but everything related to points of the compass (N, S, E, W). Gender in language: Look at the two translations of this poem by Heinrich Heine (Jewish German poet, 1797 1856): Ein Fichtenbaum steht einsam Im Norden auf kahler Höh. Ihn schläfert; mit weißer Decke Umhüllen ihn Eis und Schnee. Er träumt von einer Palme, Die, fern im Morgenland, Einsam und schweigend trauert Auf brennender Felsenwand. A pine tree standeth lonely In the North on an upland bare; It standeth whitely shrouded With snow, and sleepeth there. It dreameth of a Palm tree Which far in the East alone, In the mournful silence standeth On its ridge of burning stone. Trans. James Thomson There stands a lonely pine-tree In the north, on a barren height; He sleeps while the ice and snow flakes Swathe him in folds of white. He dreameth of a palm-tree Far in the sunrise-land, Lonely and silent longing On her burning bank of sand. Trans. Emma Lazarus From Mark Twain’s essay The Awful German Language (1880): Every noun has a gender, and there is no sense or system in distribution; so the gender of each must be learned separately and by heart. There is no other way. To do this one has to have a memory like a memorandum-book. In German, a young lady has no sex, while a turnip has. Think what overwrought reverence that shows for the turnip, and what callous disrespect for the girl. (“Where is the turnip?” “She has gone to the kitchen.” “Where is the accomplished and beautiful maiden?” “It has gone to the opera.”) “It is a bleak Day. Hear the Rain, how he pours, and the Hail, how he rattles; and see the Snow, how he drifts along, and oh the Mud, how deep he is! Ah the poor Fishwife, it is stuck fast in the Mire; it has dropped its Basket of Fishes; and its Hands have been cut by the Scales as it seized some of the falling Creatures; and one Scale has even got into its Eye. And it cannot get her out. It opens its Mouth to cry for Help; but if any Sound comes out of him, alas he is drowned by the raging of the Storm.” Number: how can ‘door’ be plural and ‘potatoes’ singular? How can a place be plural? Lexical maps seem to be culturally specific. e.g. research among Mexican and US college students: what do 'Estados Unidos' and 'United States' mean: 'Estados Unidos' – money, power, exploitation, wealth, development, progress 'United States' – love, patriotism, government, politics, freedom, justice, union Political correctness Aim: to make language less wounding or demeaning to those whose sex, race, physical condition or circumstances leave them vulnerable. Proponents of PC believe that language perpetuates prejudice. Idea that language should not insult or demean widely accepted in English-speaking countries. e.g. early Microsoft thesaurus contained 'savage' and 'man-eater' as synonyms of 'Indian' – amended after complaints e.g. Open University writing guide covers areas such as: age avoid: old fogey, old codger, old dear, old folk, the elderly, dirty old man, mutton dressed as lamb cultural diversity avoid: Blacks, non-white, coloured, Red Indian, Eskimo use: Afro-American, Black British, Native American, Inuit disability avoid: polio victim, the disabled, mental handicap use: X has polio, disabled people, people with learning difficulties gender avoid: 'he' as a general term, generic 'man', modifiers such as 'woman doctor' use: s/he, he or she, they, people/humanity, doctor PC seen by some as limiting intellectual and artistic freedom, or as censorship Enid Blyton's Noddy books from 1949 were changed in the 1980s for BBC TV series. Female character Dinah Doll introduced. Big Ears becomes White Beard. Golliwogs replaced by goblins. The PC debate different in different cultures. Which countries have legislation on sexism in advertising? USA, Canada, UK, Scandinavia, Netherlands, India. Categorisation We seem to organise what we perceive into categories. But not the same as cultural labelling. Example is the common misconception that the Inuit have more words for snow. What they do have is more technical expressions connected with snow (just as skiers or mountaineers do). Lexical and conceptual gaps If a concept is lacking in a language we can borrow, do without or invent its own label. L'Académie francaise has the task of coming up with French terms. Law in 1977 made the use of loan words in official texts illegal. What is the situation in Slovene? Borrowing is often used by bilinguals when there seems to be a gap in the target language culture: He's very simpatico. Bon appétit! We can pay him through študentski servis. English has borrowed foreign terms when conceptual equivalents are lacking: French: aide memoire, agent provocateur, avant garde, bon vivant, cachet, carte blanche, cordon bleu, crème de la crème, cul-de-sac, déjà vu, double entendre, éminence grise, en route, en suite, fait accompli, femme fatale, haute cuisine, joie de vivre, sang-froid, savoir faire, sommelier; see http://www.phrases.org.uk/meanings/french-phrases.html German: Angst, Doppleganger, Schadenfreude, Umwelt, Weltanschauung, Wunderkind, Zeitgeist Italian: al dente, (al) fresco, cupola, graffiti, Mafioso, paparazzi, prima donna More common in English is inventing new words, especially through compounding. Examples from American English (Br Eng in brackets): eggplant (aubergine), doghouse (kennel), sidewalk (pavement), boardwalk, bullfrog, catfish, bluejay, bobcat, rattlesnake, timberland, underbrush Both Sapir and Whorf later became interested in grammar as a self-contained symbolic system that reflects cultural priorities. Difficulty of translating product names and advertising slogans between languages: e.g. the brief dynamic feel of Nike's Just Do It! not really achievable in many languages. The slogan reflects the Can do US culture also seen in Obama's slogan Yes we can! Japanese attempts led to slogans with a different kind of message, e.g. Hesitation makes waste (back-translation).