Firth

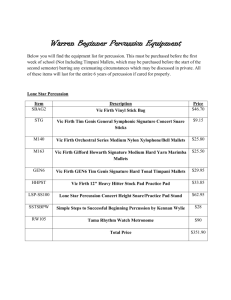

advertisement

Firth: On language and context John Rupert Firth (1890, Keighley, Yorkshire – 1960), commonly known as J. R. Firth, was an English linguist. He was Professor of English at the University of the Punjab from 1919–1928. He then worked in the phonetics department of University College London before moving to the School of Oriental and African Studies, where he became Professor of General Linguistics, a position he held until his retirement in 1956 Contributions to linguistics is work on prosody, which he emphasised at the expense of the phonemic principle, prefigured later work in autosegmental phonology. Firth is noted for drawing attention to the context-dependent nature of meaning with his notion of 'context of situation'. In particular, he is known for the famous quotation: You shall know a word by the company it keeps (Firth, J. R. 1957:11) Firth developed a particular view of linguistics that has given rise to the adjective 'Firthian'. Central to this view is the idea of polysystematism. David Crystal describes this as: an approach to linguistic analysis based on the view that language patterns cannot be accounted for in terms of a single system of analytic principles and categories ... but that different systems may need to be set up at different places within a given level of description. Context of situation Firth is noted for drawing attention to the context-dependent nature of meaning with his notion of "context of situation." The theory of the “context of the situation” became central to his approach to linguistics. For Firth, language was not to be studied as a mental system. Rather, in the spirit of positivism and behaviorism, he argued that language represents a set of events which speakers uttered—an action one learned in doing things. He believed that whatever anyone said must be understood in the context of the situation. Thus, beside linguistic factors, factors like the status and personal history of the speaker, as well as the social character of the situation, must also be taken into account. Firth described the "typical" context of situation as the occasions where we use ready-made, socially-prescribed phrases such as “How do you do?” Prosodic Analysis Firth also greatly contributed to prosody, the study of rhythm, intonation, and related attributes in speech. He first set out his phonological ideas on prosody in his Sounds and Prosodies (1948). Firth rejected purely phonemic analysis, as practiced by leading phonologists at the time (such as Nikolai S. Trubetzkoy and Leonard Bloomfield). Firth argued that there was a clear separation between phonetics and phonology. Furthermore, phonematic units and prosodies are not assumed to have obvious phonetic content, and must be accompanied by "exponency" statements explaining how a particular piece of phonological structure maps onto the phonetics. With such assumptions, Firthians were able to combine an abstract phonology with detailed phonetic description. Firth’s work on which he emphasized at the expense of the phonemic principle prefigured later work in autosegmental phonology. Phonestheme The term "phonestheme" (or "phonaestheme" in British English) was coined in 1930 by Firth (from the Greek phone = "sound," and aisthanomai = "perceive") to label the systematic pairing of form and meaning in a language. In the case of phonesthemes, the internal structure of the word is non-compositional; a word with a phonestheme in it has other material in it that is not itself a morpheme. For example, the English phonaestheme "gl-" can be found in words relating to light or vision, such as glow, glitter, glare, glisten, gleam, and so forth. The remainder of each word (-ow, -itter, -are, -isten, -eam) however is not itself a morpheme and does not make meaningful contribution to the words. Other examples of phonesthemes include "sn-," (related to the mouth or nose, as in snarl, snout, snicker, snack, and so on), and "sl-" (appears in words denoting frictionless motion, like slide, slick, sled, and so on.) Firth also studied phonological features of speech such as intonation, stress, and nasalization. He noticed that they differ considerably across languages. Legacy Among Firth's students, the so-called neo-Firthians were exemplified by Michael Halliday, who was professor of general linguistics in the University of London from 1965 until 1970. Firth encouraged a number of his students, who later became well known linguists, to carry out research on a number of African and Oriental languages. T. F. Mitchell worked on Arabic and Berber, F. Palmer on Ethiopean languages, including Tigre, and Michael Halliday on Chinese. Some other students whose native tongues were not English also worked with him and that enriched Firth's theory on Prosodic Analysis. Among his influential students were the Arab linguists Ibrahim Anis and Tammam Hassan. As a teacher in the University of London for more than 20 years, Firth influenced a generation of British linguists. The popularity of his ideas among contemporaries gave rise to what was known as the London School of Linguistics. Among Firth's students, the so-called neo-Firthians were exemplified by Michael Halliday, who was professor of general linguistics in the University of London from 1965 until 1970. At the time of his death, Firth was recognized as the utmost leader of British linguistics. Outside of Great Britain however, Firth’s influence was limited. Although he lectured abroad, especially in the United States, he never gained any significant support for his views. In the U.S. it was Kenneth L. Pike who acknowledged Firth’s ideas. In the 1960s and 1970s, many of Firthian ideas were challenged by general generative linguistics and overtaken by the work of Morris Halle and Noam Chomsky. Some basic ideas of Firth, however, survived and were taken up by his student Michael Halliday, who founded Systemic Functional Linguistics. Also, the theory that the autonomous phoneme is an untenable object can be traced to Firthian linguistics.