In 1974, Eleanor Maccoby & Carol Jacklin

advertisement

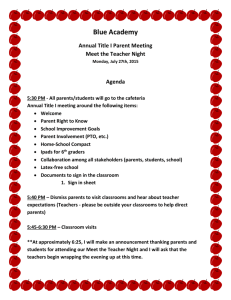

Meg Shoemaker April 27th, 2010 Gendering in Early Education: Where has the discussion led us? In the late twentieth century the debate about sex stereotypes, sex differences, and gendering took the forefront in a number of realms: theology, psychology and most importantly, education. One of the most integral parts of an American child’s life is his or her formative years in school. For seven hours a day, five days a week children are being socialized by the institution of the school, the adults who teach them, and their peers. Information learned at school will remain a foundation for the individual, and the school setting will continue to be a socializing mechanism for society at large. So what are children learning about gender at school? In 1974, Eleanor Maccoby, a trail-blazer in the field of psychology and sex differences, teamed up with Carol Jacklin to publish their research in The Psychology of Sex Differences. Move forward twenty-six years, and Anna Coffey, a social science researcher, and Sara Delamont, a sociologist, analyze the ways in which teachers can minimize gendering in their classrooms. The discussion and research surrounding teachers’ effect on gender in early education has increased dramatically since Maccoby and Jacklin’s first exploration into sex differences. The viable approaches recommended are single-sex classrooms and educating teachers about non-gendering practices, but they still need some critiquing; few address race, class, and culture in relation to gendering in the classroom. And through the discussion, research, and approaches about teachers effect on gender comes the answers of whether or not children benefit from the gender attention. 1 Eleanor Maccoby and Carol Jacklin were two of the first researchers to study how boys’ learning is different than girls’ learning. Instead of focusing on the variations of learning processes, they focused on the children’s “achievements [as a] result of past learning, inherent capacity, motivation and interests, or some interweaving of these factors” (Maccoby 15). In the mid-1970s, of the three theories of how children learned gender (imitation, praise or discouragement, and self-socialization), the prevailing discourses said that socializing agents were directly shaping the gendering of children. Maccoby & Jacklin got right to the heart of the matter and researched the social shaping of sex-typical behavior. They disclaimed some ‘assumptions’ of the time: “That girls are better at rote learning and simple repetitive tasks, boys at tasks that require higher-level cognitive processing and the inhibition of previously learned responses” and “that girls lack achievement motivation” (350-351). Girls were therefore not less smart than boys or less motivated, but there was something different regarding the ways that they learned the material. Psychologist Carol Gilligan picked up the sex differences debate in her book, In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development, published in 1982. Gilligan wrote the book when second wave feminists were taking over the fight to end sexism but at the same time they were beginning to find it was prevalent in most aspects of life – what were presented as objective scientist reports and histories of America were in fact men’s observations of science and history. Critiquing such ‘objective’ parts of life left Gilligan realizing how researchers had fallen into the trap that Simone de Beauvoir wrote about: Man vs. Other. Man’s perspective, also known as The One’s perspective, is taken as universal, and it is this essentialism that negates women’s perspectives as 2 important and necessary. Gilligan theorizes that “instead, the failure of women to fit existing models of human growth may point to a problem in the representation, a limitation in the conception of human condition, an omission of certain truths about life” (2). Gilligan is disappointed with the research done in the psychology area so she postulates the ‘different voice:’ Woman’s voice and experience which is not less good and true than Man’s voice, but simply different. Gilligan goes so far as to say that even knowledge is a construct. So if Man constructs knowledge, then in the context of gender in education, one must look at the affect of the adult teachers, in charge of transferring the constructed knowledge, as to how they construct the knowledge of gender in the children. Gilligan and Maccoby & Jacklin agree that gender is socialized, but they do not really hypothesize what the socializing of gender looks like. Educational institutions want to shape the mind. One way they do so is by shaping the body. Maccoby & Jacklin claim that physical differences of gender are obvious but the psychological differences are not, but Delamont and sociologist Karin Martin find problems with that claim because they believe that the obvious body itself is gendered by social forces. Delamont works with Maccoby & Jacklin’s sex differences theory in the school setting. Delamont observes elementary aged children who, she points out, have not gone through puberty yet. The children’s physical bodies are almost the same but schools still use segregational practices to differentiate children. Sex is used to separate bathrooms, and it is used as an organizing assistant in classroom management. Delamont is joined by Martin’s research in finding that the education system is a microcosm that reinforces gender roles that are similarly enforced in the macrocosm of society. 3 Whereas Delamont points out the similarity of young girls’ and boys’ bodies, Martin concludes that “these bodily differences enhance the seeming naturalness of sexual and reproductive differences, that then construct inequality between men and women…these differences create a context for social relations in which differences confirm inequalities of power” (62). In Delamont’s and Martin’s reports, teachers complimented little girls on their hair and clothes and ‘fixed’ their clothing when needed. Girls wearing dresses, which ranged from fourteen percent to thirty-two percent depending on their age, were limited in their physicality because of the tights and dress initially and also in the behavior that they are supposed to adhere to while wearing the dress (Martins 498). Boys tended to act out and receive more attention from teachers, thus reinforcing such behavior. Several contemporary theories deal with the problem of gendering in education. Some hold the teacher accountable, others the inclusion of boys and girls in the same classroom. Anna Coffey and Sara Delamont provide one solution to the problem of gendering in the classroom. They believe that they could change coed classrooms and teachers’ perspectives on gender by integrating the feminist perspective into the education system. Teachers could use the “‘privacy’ of classrooms as opportunity rather than risk, set up classrooms to encourage collaboration and create feminized spaces, use management strategies that foster democratic and social justice values” (Coffey 27). Coffey & Delamont want the teachers to take on the challenge of Gilligan’s ‘knowledge is a construct’ and construct an education where children are treated as individuals and not a gender stereotype. 4 Research conducted by Barbara Bianchi, a professor of neonatal and prenatal medicine, and Roger Bakeman, a professor of psychology, is based on observation of an open school and a traditional school. The open school puts an “emphasis on the individual development of each child…thus sex-stereotyped expectations about children’s interests, abilities, or personalities are consciously avoided” (Bianchi 223). Their findings proved that students, taught by teachers who deconstructed gender, displayed less sex-stereotyped behaviors and attitudes. Boy and girls interacted more and there was a “redefining of the aspects of a child’s life that are regarded as the exclusive property of one sex or the other” (Bianchi 231). Though the children themselves adhered less to sex-stereotypes they understood that the stereotypes did appear in the larger social arena. This reveals that although the school they attended for a majority of the week may adhere to a non-sex stereotyped education, they were still influenced by the gendered world at large through their home life and the influences of the home lives of the peers in their class. On the other hand, a similar study done four years later by Howard Cole et al. produced contradictory findings. Cole et al. found no conclusive evidence that children cared for in a daycare that adhered to a non-sexist child-rearing philosophy showed less culturally typical patterns of gender role behavior than their counterparts. The two settings were a traditional day-care and a non-traditional day-care. The non-traditional day-care center staff “adhered to a ‘non-sexist’ child rearing philosophy” which was played out by the equal distribution of tasks and responsibilities by the staff (comprised of men and women), as well as children not being encouraged or discouraged to participate in various activities because of their gender, and the staff and parents 5 “routinely discussed and explored issues of sexism and non-sexism both in formal meetings and in the day-to-day running of the centre” (Cole 413, 411). Cole et al.’s methodology included two task assessments (free-play task and asking the child to draw a person and label its sex) and a home visit where the researcher document the toys found in the child’s room and administering a parent questionnaire. Cole et al. hypothesize that though the adults in the study, who either worked at the non-traditional day-care or sent their children to it, believe that they are raising less sexist children, their actions might not be as non-sexist as they hoped for. Cole et al.’s methodology does gauge gender-role behavior but researchers would need to look first at the specific actions and behaviors of the non-traditional or open school’s educators in order to get conclusive results of whether teachers gender their students or not. Another practice that addresses gender issues in education is the single-sex classroom. Margrét Ólafsdóttir first brought single-sex education to Iceland in 1989. In her article “Kids Are Both Girls and Boys in Iceland,” she describes the Hjalli Model of schooling which is based on the recognition of diversity through sex segregated classrooms within a coed institution. Girls are taught to be daring and make noise while boys are taught massage and ways to express caring. Ólafsdóttir seems to have set up an educator’s utopia with segregation of sexes as its core and non-consumerism thrown in the mix as well. The children combine for coed activities everyday and all seems to flow by Ólafsdóttir’s motto: “Segregation is the method, integration is the goal” (368). Though the Icelandic society might play a major role in the success of this specific single-sex classroom school, Ólafsdóttir’s findings and theories could be used in the United States and benefit the children involved immensely. 6 The United States enforced “separate but equal” before and at the time the reality was anything but equality. Regarding classrooms segregated by gender being equal, however, distinguished law professor and researcher Rosemary Salomone has determined that single-sex classrooms are legal. Though some are slightly faulted, there are overwhelmingly good things going on in these classrooms; Salomone has found that “allgirl settings seem to provide girls a certain comfort level that helps them develop greater self-confidence and broader interests, especially as they approach adolescence” (239). Salomone’s main critique of the education system and the research done on single-sex classrooms is that they still do not look at the issues of race, class and culture and how they intersect and complicate gender. It will make research more difficult but contemporary research should not exclude these intricacies. Through my research and interviews with the education faculty at St. Olaf College I developed a proposal to study the problem of gendering in education. In the education curriculum gender is never explicitly considered as an education issue; it is grouped under the umbrella of ‘diversity.’ The future teachers of America are taught to treat children as individuals, blind to gender, race, class and culture. For their certification, student-teachers must work in at least one classroom that is diverse and they will have usually read a book or two that deals with the broad topic of diversity and might specifically deal with gender in one chapter. If future teachers are not being adequately prepared to recognize their own gender biases in the classroom as a precondition to treating children as individuals, not as gender stereotypes, can we expect that they will automatically know how to do it? 7 Race, class, and culture are interwoven with gender, but I want to begin looking at the intricacies of these issues through gender. According to Lyn Martinez, an author and researcher involved in gender equity policies in Queensland and Australia in the 1990’s, the societal benefits of a less gendered childhood education system are “the elimination of gendered violence; the achievement of a more equitable distribution of male and female labour across the paid workforce, the community and the work of private caring; and the development of a concept of citizenship that places value on achieving equality, democracy and human rights” (120). I think it is important to understand the outcomes of educators’ work with gender, and to teach the educators of the future the impact they can have on children’s lives when they deconstruct gender in their classrooms. By combining Coffey & Delamont’s theory of teaching through a feminist perspective, with Cole et al.’s critique of inaccurate non-sex-stereotyping practices, we could teach educators to analyze carefully their own behavior and practices that reflect gendering in the classroom. Teachers in both coed classrooms and single-sex classrooms would have to figure out how to integrate this information on gender into their classrooms. Then we could research those classrooms to see if the teachers’ influence on gender can be eliminated. We would also need to look for ways in which class, race, and culture play into gender. Single-sex classrooms are not financially viable in all situations so they are not the answer for every community. Coed classrooms pose greater resistance to deconstructing gender. But, given a consistent non-gendering teacher base both classrooms can work towards the common good that Martinez has envisioned such as equitable diffusion of male and female work in the public and private sphere and the elimination of gender violence. 8 Annotated Bibliography Bianchi, Barbara D., and Roger Bakeman. Patterns of Sex Typing in an Open School. Social and Cognitive Skills; Sex Roles and Children's Play. New York: Academic, 1983. 219-33. Print. Bianchi, a professor of neonatal and prenatal medicine, and Bakeman, a professor of psychology, conducted a three-year research project to observe the behavior of the students in an open school. At the open school the teachers focused on the individual child by not making expectations based on gender and tried to have a male teacher and a female teacher in the classroom at all times. They found that the children had a narrower view of sex-role stereotypes which translated into greater mixed-gender play and lack of sex-stereotyped activities maintaining their segregation. This report was based on the published research of Bianchi and Bakeman in 1978, and ten years later Howard Cole et al. conducted a similar experiment and found that there were no gender-role behavior differences between the children in a traditional daycare versus a non-traditional daycare. Coffey, Amanda, and Sara Delamont. Feminism and the Classroom Teacher: Research, Praxis, Pedagogy. London: Routledge/Falmer, 2000. Print. Coffey, a professor of social sciences, and Delamont, a sociologist work together to explore the specific areas in which feminist scholarship could change the classroom and the teacher’s perspectives: using the privacy of the classroom to set up a gender neutral area and use management styles that foster working together and equality. The research and literature have international grounding and uses various types of 9 research modes and perspectives; twenty years earlier Delamont claimed in Sex Roles and the School (1980) that there was no prior research on the gendering of classrooms but twenty years later there is now an inexhaustible amount of material available. This work builds on the gender neutral work done in coed classrooms and gives new ways of improving it. Cole, Howard J., Kenneth Zucker, and Susan Bradley. "Patterns of Gender-role Behaviour in Children Attending Traditional and Non-traditional Day-care Centers." The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 27.5 (1982): 410-14. PsycINFO. Web. 8 Mar. 2010. Zucker, a well-published researcher in gender identity studies, lead his team to find that there was no conclusive evidence that children cared for in a daycare that adhered to a non-sexist child-rearing philosophy showed less culturally typical patterns of gender role behavior than their counterparts. Cole et al.’s methodology included two task assessments (free-play task and asking the child to draw a person and label its sex) and a home visit where the researcher document the toys found in the child’s room and administering a parent questionnaire. Howard et al.’s findings differ from Bianchi’s findings of a similar study. Delamont, Sara. Sex Roles and the School. London: Methuen, 1980. Print. At the time, there had been few studies that focused on gender differences in classrooms so Delamont, a sociologist, used works about ‘women and education’ and ‘women and society’ to inform her writing. Primarily a work in feminist sociology, the 10 book is written more from a sociological point of view than a feminist one. The book argues that the education system reinforces gender roles that are also enforced in society. Gilligan, Carol. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1982. Print. Gilligan, a famous ethicist, psychologists, and feminists, is disappointed with the research done in psychology because it pins man as correct and misrepresents any differences between men and women as being a failure on the part of the women. Knowledge is a human construct, so she critiques others’ research and helps to look at the misrepresentations through a feminist lens so that the reader can understand how the social context of the research can be shading its results. Gilligan lays out the basis for the need to study education and how the experiences boys and girls have could be different. Maccoby, Eleanor Emmons., and Carol Nagy. Jacklin. The Psychology of Sex Differences. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford UP, 1974. Print. Maccoby, a trail-blazer in the field of psychology and sex differences, teams up with Jacklin to a follow up on the book Maccoby edited in 1966, The Development of Sex Differences. The authors are among the first to look at social shaping of sex-typical behavior. Also, they analyze the widely held beliefs and based on the research, disclaim some of them such as ‘Girls lack achievement motivation.’ The book is one of the first of 11 its kind to try to look at the why’s of sex differences and see how they could play out in the learning development of the child as well as how the child is socialized. Martin, Karin A. “Becoming a Gendered Body: Practices of Preschools.” 1998. Reading Women's Lives. Boston: Pearson Custom, 2005. 39-66. Print. Martin, a sociologist, has written on the gendering of the female body since 1993. Martin calls attention to the lack of study around the process of gendering girls’ bodies in contrast to the larger debate surrounding the gendered adult woman’s body. The article explores bodily adornment, formal and relaxed behaviors, controlling voice, bodily instructions, and the physical interaction between teachers and children and children and their peers. Through these observations, Martin concludes that teachers teach and reinforce gender. Martinez, Lyn. "Gender Equity Policies and Early Childhood Education." Gender in Early Childhood. New York: Routledge, 1998. 115-30. Print. Martinez was involved in gender equity policies in Queensland and Australia in the 1990’s and believes that some adults worry about politicizing their children at too young of an age. In most cases children have already begun to define themselves politically by the time they reach elementary school. Martinez states that there would be an elimination of gendered violence, an equal distribution of works across the paid workforce and the private home maintenance, and a development of citizenship that puts value on the work done by an individual if the education system was less 12 gendered. It is necessary to have the tangible outcomes written out so that parents and other educators can see the long term goals while working in the present. Ólafsdóttir, Margrét. "Kids Are Both Girls and Boys in Iceland." Elsevier Science Ltd. (1996). Women's Studies International Forum. Web. 1 Mar. 2010. Ólafsdóttir first brought single-sex education to Iceland. In the article, she describes the Hjalli Model of schooling which is based on the recognition of diversity through sex segregated classrooms. Girls are taught to be daring and make noise while boys are taught massage and ways to express caring. Ólafsdóttir’s model is one answer to gendering problems in education, and where as some single-sex classrooms include sex stereotyping the ones she sets up are dedicated to helping the individual become less gendered according to sex. Salomone, Rosemary C. Same, Different, Equal: Rethinking Single-sex Schooling. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. Print. Salomone is a distinguished law professor who used her researching and analytical skills to critique single-sex education. She found faults but also merits, such as greater self-confidence, that can be built on to create an education system that focuses on the individual regardless of their sex. It does not provide any alternative methods of removing gendering from the classroom though it finds faults with some same-sex classrooms. Single-sex education is one of the ways individuals have tried to correct the gendering problem in schools, and this book thoroughly critiques this answer. 13