on linking formative and summative functions

advertisement

ON LINKING FORMATIVE AND SUMMATIVE FUNCTIONS

IN THE DESIGN OF LARGE-SCALE ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

Richard J. Shavelson1

Stanford University

Paul J. Black, Dylan Wiliam

Kings College London

Janet Coffey

Stanford University

Submitted to Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis

Abstract

The potential for mischief caused by well-intended accountability systems is legion when

expedient output measures are used as surrogates for valued outcomes. Such misalignment

occurs in education where external achievement tests are not well aligned either with

curriculum/standards, or high-quality teaching methods. Tests become outcomes themselves

driving curriculum, teaching and learning. We present three case studies that show how polities

have crafted assessment systems that attempted to align testing for accountability (“summative

assessment”) with testing for learning improvement (“formative assessment”). We also describe

how two failed to achieve their intended implementation. From these case studies, we set forth

decisions for designing accountability systems that link information useful for teaching and

learning with information useful to those who hold education accountable.

1

School of Education, 485 Lasuen Mall, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-3096; 650-723-4040

(telephone); 650-725-7412 (fax). richs@stanford.edu.

ON LINKING FORMATIVE AND SUMMATIVE FUNCTIONS

IN THE DESIGN OF LARGE-SCALE ASSESSMENT SYSTEMS

The proposition that democracy requires accountability of citizens and officials is a universal

tenet of democratic theory. There is less agreement as to how this objective is to be

accomplished—James March and Johan Olsen (1995, p. 162)

Democracy requires that public officials, public and private institutions, and individuals

be held accountable for their actions, typically by providing information on their actions and

imposing sanctions. This is no less true for education, public and private, than other institutions;

the demand for holding schools accountable is part of the democratic fabric.

The democratic concept of accountability is noble. However, in practice it can fall short

of the ideal. For, as March and Olsen (1995, p. 141) put it, “The events of history are frequently

ambiguous.

Human accounts of those events characteristically are not.

Accounts provide

interpretations and explanations of experience” that make sense within a cultural-political

framework.

They (March & Olsen, p. 141) go on to point out that, “Formal systems of

accounting used in economic, social and political institutions are accounts of political reality”

(e.g., students’ test performance represent outcomes in a political reality). As such, they have

profound impact on actors involved. On the one hand, accounts focus social control and make

actors responsive to social pressure and standards of appropriate behavior; on the other hand, they

tend to reduce risk-taking that might become public, make decision making cautions about

change, and reinforce current courses of action that have appeared to have failed (March, 200?).

In this paper our focus is on human educational events—teaching, learning, outcomes—

that are by their very nature ambiguous but get accounted for unambiguously in the form of test

scores, league tables, and the like with significant impact on education. For accountability

information, embedded in an interpretative, political framework, is, indeed, a very powerful

policy instrument. Yet the potential for mischief is legion. Our intent is to see whether or not we

can improve on one aspect of accountability—that part that deals with information—to improve

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

3

both its validity and positive impact. Specifically, our intent is to set forth design choices for

accountability systems that link, to a greater or lesser extent, information useful to teaching and

learning with information useful to those holding education responsible—policy makers, parents,

students, and citizens. For the current mismatch between information to improve teaching and

learning, and information to inform the public of education quality has substantial negative

consequences on valued educational outcomes.

Before turning to the linkage issue, a caveat is in order. To paraphrase March and Olsen,

educational events are frequently ambiguous… and messy, complicated and political. To focus

this paper, we are guilty in the portrayal of educational events and our “human accounts of those

events are characteristically not [ambiguous]” but should be. Teachers, for example, face conflict

every day in gathering information on student performance–to help students close the gap

between what they know/can do and what they need to know/be able do on the one hand, and to

evaluate students’ performance for the purpose of grading on the other hand. This creates

considerable conflict and complexity that, due to space, we have reluctantly omitted (see, for

example, Atkin, Black & Coffey, 2002; Atkin & Coffey, 2001). .

The Linkage Issue

In a simple minded way, we might think of education as producing an outcome such as

highly productive workers, enlightened citizens, life-long learners or some combination of these.

Inputs (resources) are transformed through a process (use of resources) into outputs (products)

that are expected contribute to the realization of valued outcomes. “With respect to schools, for

example, inputs include such things as teachers and students, processes include how teachers and

students spend their time during the school day, outputs include increased cognitive abilities as

measured by tests, and outcomes include the increased capacity of the students to participate

effectively in economic, political and social life” (e.g., Gormley & Weimer, 1999, pp. 7-8).

When outputs are closely and accurately linked to inputs and processes on the one hand,

and to outcomes on the other, the accounts of actors and their actions may be valid—they may

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

4

provide valuable information for improving the system (processes given inputs) on the one hand,

and for accounting to the public for outcomes on the other. However, great mischief can be done

by an accountability system that does not, at least, closely link outputs to outcomes. For outputs

(e.g., broad scope multiple-choice test scores) quickly become valued outcomes from the

education system’s perspective, and the information provided by outputs may not provide

information either closely related to outcomes or needed to improve processes.

Current educational accountability systems use large-scale assessments for monitoring

achievement over time. They can be characterized as outputs (e.g., broad-spectrum multiplechoice or short-answer questions of factual or procedural recall) that are either distal from

outcomes and processes or that have become the desired outcomes themselves. Consider, for

example, the algebra test item:

Simplify, if possible, 5a + 2b (Hart, Brown, Kerslake,

Kuchemann, & Ruddock, 1985). Many teachers regard this item unfair for large-scale testing

since students are “tricked” into simplifying the expression because of the prevailing “didactic

contract” (Brousseau, 1984) under which students assume that there is “academic work” (Doyle,

1983) to be done; doing nothing cannot be academic work with the consequence of a low mark.

The fact that they are tempted to simplify the expression in the context of a test question when

they would not do so in other contexts means that this item may not be a very good question to

use in a test for external accountability purposes.2

Indeed, testing for external accounting purposes may not align with testing for improving

teaching and learning. Accountability requires test standardization while improvement may

involve dynamic assessment of learning; testing for accountability typically employs a uniform

testing date while assessment for improvement is on-going, testing for accountability leaves the

student unassisted while assessment for improvement might involve assistance, results of

accountability tests are delayed while assessment for improvement must be immediate, and

2

However, such considerations do not disqualify it for purposes of improving the teaching-learning process

because a student being tricked may be important information for the teacher to have indicating the

students’ insecurity with basic algebraic principles.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

5

testing for accountability must stress reliability while clinical judgment plays an important role

over time in improvement (Shepard, 2003). Note that this version of accountability reflects

current education practice.

It is not inevitable, as Jim March reminds us:

There is little

agreement on how to accomplish democracy’s accountability function and this is especially true

in education.

The potential for mischief and negative consequences is heightened when public

accountability reports are accompanied by strong sanctions and rewards, such as student

graduation or teacher salary enhancements. Test items may be stolen, teachers may teach the

answers to the test, and administrators may change students’ answers on the test (e.g., Assessment

Reform Group, 2002; Black, 1993; Shepard, 2003).

In this paper, we set forth design choices for tightening the links among educational

outputs, the processes for improving performance on them, and desired outcomes. We begin with

a framework for viewing assessment of learning for improving teaching-learning processes and

for external accounting purposes. We then turn attention to large-scale assessment systems that

have attempted alignment as existence proofs and as sources for identifying large-scale

assessment design choices. To be sure, alignment has been attempted in the past with varying

degrees of success.

From these “cases” we extract design choices, choices that are made,

intentionally or not, in the construction of large-scale assessment systems. We then show the

pattern of design choices that characterize each of our cases.

Functions of Large-Scale Assessments: Evaluative, Summative and Formative

Large-scale testing systems may serve three functions: Evaluative, summative and

formative. The first function is evaluative. The system provides (often longitudinal) information

with which to evaluate institutions and curricula. To this end, the focus is on the system; samples

of students, teachers, and schools provide information for drawing inferences about institutional

or curricular performance. The National Assessment of Educational Progress in the United States

and the Third International Mathematics and Science Study are examples of the evaluative

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

6

function. We are not concerned here with this function3; rather we focus on summative and

formative functions of assessment.

The second function is summative. The system provides direct information on individual

students (e.g., teacher grades—not our focus here—and external test scores) and, by aggregation,

indirectly on teachers (e.g., for salaries) and schools (for funding) for the purpose of grading,

selecting, and promoting students certifying their achievement, and for accountability. The

General Certificate of Secondary Education examination in the United Kingdom (e.g.,

http://www.gcse.com/) is one example of this function as are statewide assessments of

achievement in the United States such as California’s Standardized Testing and Reporting

program

(http://star.cde.ca.gov/)

or

the

(http://www.scotthochberg.com/taas.html/).

Texas

Assessment

of

Academic

The third function is formative.

Skills

The system

provides information directly and immediately on individual students’ achievement or potential to

both students and teachers. Formative assessment of student learning can be informal when

incidental evidence of achievement is generated in the course of a teacher’s day to day activities,

when the teacher notices that a student has some knowledge or capacity of which she was not

previously aware. Or it can be formal as a result of a deliberate teaching act designed to provide

evidence about a student’s knowledge or capabilities in a particular area. This most commonly

takes the form of direct questioning (whether orally or written),4 but also in the form of

curriculum embedded assessments (with known reliability and validity) that focus on some aspect

of learning (e.g., mental model of the sun-earth relationship that accounts for day and night or a

change in seasons) and that permits the teacher to stand back and observe performance as it

3

We believe that this function is often confounded with the summative function (see below) where the

focus is on institutional evaluation and a census of students (etc.) is taken to provide feedback on individual

achievement as well as on institutional performance.

4

Of course questioning, formally or informally, will not guarantee that if the student has any knowledge or

understanding in the area being answered, then evidence of that attainment will be elicited. One way of

asking a question might produce no answer while a slightly different approach may elicit evidence of

achievement.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

7

evolves. The goal here is to identify the gap between desired performance and a student’s

observed performance so as to improve student performance through immediate feedback on how

to do so. Formative assessment also provides “feed-forward” to teachers as to where, on what,

and possibly how to focus their teaching immediately and in the future.

While most people are aware of summative assessment, few are aware of formative

assessment and the evidence of its positive, large-in-magnitude impact on student learning (e.g.,

Black & Wiliam, 1998). Perhaps a couple of examples of formative feedback, then, would be

helpful.

Consider, for instance, teacher questioning, a ubiquitous classroom event.

Many

teachers do not plan and conduct classroom questioning in ways that might help students learn.

Rowe’s (1974) research showed that when teachers paused to give students an opportunity to

answer a question, the level of intellectual exchange increased. Yet teachers typically ask a

question and give students about one second to answer. As one teacher came to realize (Black,

Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliam, 2002, p. 5):

Increasing waiting time after asking questions proved difficult to start with—due to my

habitual desire to ‘add’ something almost immediately after asking the original question.

The pause after asking the question was sometimes ‘painful’. It felt unnatural to have

such a seemingly ‘dead’ period, but I persevered. Given more thinking time students

seemed to realize that a more thoughtful answer was required. Now, after many months

of changing my style of questioning I have noticed that most students will give an answer

and an explanation (where necessary) without additional prompting.

As a second example, consider the use of curriculum-embedded assessments. These

assessments are embedded in the on-going curriculum. They serve to guide teaching, and create

an opportunity for immediate feedback to students on their developing understandings. In a joint

project between the Stanford Education Assessment Laboratory and the Curriculum Research and

Development Group at the University Hawaii, modifications have been made to the Foundational

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

8

Approaches in Science Teaching (FAST) middle-school curriculum.

A set of assessments

designed to tap declarative knowledge (“knowing that”), procedural knowledge (“knowing how”)

and schematic knowledge (“knowing why”) have been embedded at four natural transitions or

“joints” in an 8-week unit on buoyancy—some assessments are repeated to create a time series

(e.g., “Why do things sink or float?”) and some (multiple-choice, short-answer, concept-map,

performance assessment) focus on the particular concepts, procedures and models that led up to

the joints. The assessments serve to focus teaching on different aspects of learning about mass,

volume, density and buoyancy. Feedback on performance is immediate, focuses on constructing

conceptual understanding based on empirical evidence. For example, assessment items (graphs,

“predict-observe-explain,” and short answer) that tap declarative, procedural and schematic

knowledge are given to students at a particular joint. Students debate different explanations of

sinking and floating based on evidence in hand.

While the dichotomy of formative and summative assessment seems perfectly

unexceptional, it appears to have had one serious consequence. Significant tensions are created

when the same assessments are required to serve multiple functions, and few believe that a single

system can function adequately to serve both functions. At least two coordinated or aligned

systems are required: formative and summative.

Both functions require that evidence of

performance or attainment is elicited, is then interpreted, and as a result of that interpretation,

some action is taken. Such action will then, directly or indirectly, generate further evidence

leading to subsequent interpretation and action, and so on.

Tensions arise between the formative and summative functions in each of three areas:

evidence elicited, interpretation of evidence, and actions taken. First, consider evidence. As

Shepard (2003) pointed out, issues of reliability and validity are paramount in the summative

function because, typically, a “snapshot” of the breadth of students’ achievement is sought at one

point in time. The forms of assessment used to elicit evidence are likely to differ from summative

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

9

to formative. In summative assessment, typical “objective” or “essay” tests are given on a

particular occasion. In contrast, with formative assessment, students’ real-time responses are

given to one another in group work, to a teacher’s question, to the activity they are engaged in or

to a curriculum-embedded test. Moreover, the summative and formative functions differ in the

reliability and validity of the scores produced. In summative assessment, each form of a test

needs to be internally consistent and scores from these forms need to be consistent from one rater

to the next or from one form to the next. The items on the tests need to be a representative

sample of items from the broad knowledge domain defined by the curriculum syllabus/standards.

In contrast, as formative assessment is iterative, issues of reliability and validity are resolved over

time with corrections made as information is collected naturally in everyday student performance.

Finally, the same test question might be used for both summative and formative assessment but,

as shown with the simplify item (simplify 5a + 2b), interpretation and practical uses will probably

differ (e.g., Wiliam & Black, 1996).

The potential conflict between summative and formative assessment can also be seen in

the interpretation of evidence. Typically, the summative function calls for a norm-referenced or

cohort-referenced interpretation where students’ scores come to have meaning relative to their

standing among peers. Such comparisons typically combine complex performances into a single

number and put the performance of individuals into some kind of rank order. A norm- or cohortreferenced interpretation would indicate how much better an individual needs to do, pointing to

the existence of a gap, rather than giving an indication of how that improvement is to be brought

about. It tells the individual that they need to do better rather than telling him or her how to

improve.5

5

Nevertheless, summative information can be used for formative purposes, as for example when statistics

and interpretations are published, as they are in Delaware, for science items on a summative assessment

and thereby serve as benchmarks for what teachers and parents can reasonably expect students to achieve

(see Wood & Schmidt, 2002; see also Shepard 2003).

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

10

The alternative to norm-referenced interpretation in large-scale assessment is criterion- or

domain-referenced interpretation with focus on amount of, rather than rank ordering on,

knowledge. Summative assessment, in this case, would report on the level of performance of

individuals or schools (e.g., percent of domain mastered), perhaps with respect to some desired

standard of performance (e.g., proportion of students above standard).

In this case, the

summative assessment would, for example, certify competence.6

Formative assessment, in contrast, provides students and teachers with information on

how well someone had done and how to improve, rather than on what they have done and how

they rank. For this purpose, a criterion- or domain-referenced interpretation is needed. Such an

interpretation focuses on the gaps between what a student knows and is able to do with what is

expected of a student in that knowledge domain. However, formative assessment goes beyond

domain referencing in that it also needs to be interpreted in terms of learning needs—it should be

diagnostic (domain-referenced) and remedial (how to improve learning). The essential condition

for an assessment to function diagnostically is that it must provide evidence that can be

interpreted in a way that suggests what needs to be done next to close the gap.

The two assessment functions also differ in the actions that are typically taken based on

their interpretations. Summative assessment reaches an end when outcomes are interpreted.

While there may be some actions contingent on the outcomes, they tend to follow directly and

automatically as a result of previous validation studies. Students who achieve a given score on

the SAT are admitted to college because the score is taken to mean that they have the necessary

aptitude for further study.

One essential requirement here is that the meanings and significance

of the assessment outcomes must be widely shared. The same score must be interpreted in the

same way for different individuals.

6

The value, implications and social consequences of the

For an aircraft pilot, the issue is pass or fail; good take off but dodgy on the landing is of little value!

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

11

assessment, while generally considered important, are often not considered as aspects of validity

narrowly defined (Madaus, 1988), but are central to a broader notion of validity (Messick, 1980).

For formative assessment, in contrast, the learning caused by the assessment is

paramount. If different teachers elicit different evidence from the same individual, or interpret

the same evidence differently, or even if they make similar interpretations but take different

actions, this is relatively unimportant. What really matters is whether the result of the assessment

is successful learning. In this sense, formative assessment is validated primarily with respect to

its consequences.

The potential for summative and formative assessment to work at cross-purposes, then, is

enormous. However, too much is at stake to leave them in natural conflict. If left in conflict, the

summative function will overpower the formative function and the goals of education may be

reduced to the outputs measured by standardized tests that rank order performance and relate it to

a peer group. The goal of teaching and education becomes improving scores on these tests, and

all kinds of unintended consequences arise including cheating.

What is at stake is the evidence of a positive, large-in-magnitude impact that the

formative function makes on student learning (Assessment Reform Group, 2002; Black &

Wiliam, 1998). It becomes imperative, then, to align formative and summative assessment. We

believe this might be done in two general ways: (1) broaden the evidence base to include a greater

range of outcomes that goes into summative assessment to include formative information, or (2)

aggregate formative assessment information as the basis of the summative function. We turn to

case studies of both approaches as “existence proofs.”

Attempts to Align Large-Scale Formative and Summative Assessment

Attempts that have been made to align large-scale summative assessment with formative

assessment have met with a greater and lesser degree of success. We focus on three cases not

because they are exhaustive but because they are illustrative of the larger domain.

The

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

12

conceptual framework and procedures employed in each of these different cases provide an image

of how the summative and formative functions of assessment might be linked. They also provide

lessons in the difficulty of achieving alignment in hotly contested, political environments where

differing conceptions of teaching and learning as well as questions of cost effectiveness come into

play. We begin with two attempts to include formative information in summative, large-scale

assessments of achievement: The California Learning Assessment System in the U.S. and the

Task Group on Assessment and Testing’s framework for reporting national curriculum

assessment results in the U.K. We then turn attention to a different case, one that built a

summative assessment system on formative assessment.

Our intent is to provide concrete

examples from which we might draw implications for large-scale assessment design choices.

California Learning Assessment System

The California Learning Assessment System (CLAS) sought to link formative with

summative assessment of student achievement in grades 4, 8 and 10. The legislation (Senate Bill

SB-1273) was written in 1991 in response to Governor Pete Wilson’s promise to citizens of the

State to create an achievement assessment system that provided timely and instructionally

relevant information to teachers, to individual students and their parents, and to the State. This

promise reflected what were seen as limitations to the then California Assessment Program

(CAP) that indexed the achievement of California’s 4th, 8th, and 10th grade students in the

aggregate (i.e., by matrix sampling) rather than at the individual student level (i.e., evaluative

function of assessment). CAP, then, was unable to provide reliable scores to students who took

only a subset of test items. Moreover, CLAS was to be aligned with the new curriculum

frameworks that embraced constructivist, inquiry principles of learning and teaching so that, in

addition to traditional tests (i.e., multiple-choice), alternative assessments (essays in English,

performance assessments in science, mathematics and history) would be incorporated into the

assessment system.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

13

In order to meet the Governor’s vision of providing timely achievement information to

teachers, students and parents, CLAS was designed to combine information from on-demand

testing, classroom embedded testing and classroom portfolios (see Figure 1). Like CAP, at least

initially, CLAS would include on-demand statewide testing where students would sit for a

multiple-choice test (Figure 1-A). Unlike CAP, however, the test would not contain just a sample

of items for each student. Rather, all students would take the same test so that individual scores

could be given to teachers, students and parents. Over time (see below), individual student

information would come from classroom data sources and the on-demand aspect of CLAS would

simply be an audit of classroom data through sampling.

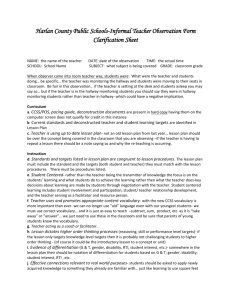

Insert Figure 1. Sources of CLAS data.

In order to provide timely, curriculum-relevant feedback to teachers and students, CLAS

envisioned embedding state-designed tests into the ongoing curriculum (Figure 1-B).

For

example, the State might provide writing prompts for all 8th grade English teachers to administer

and score (using a State developed rubric) five times in the academic year. Or the State might

provide 4th grade teachers with a 5-day mini-science curriculum on (say) biodiversity that

incorporated performance assessments (practical/laboratory investigation) that a teacher would

score immediately using a state-provides rubric. Such an exercise might be carried out three

times in the year. In this way, feedback on student performance would be immediate in the

classroom and the data could then be passed on to the state for further processing with the intent

of producing school, aggregate school (by demographics), district and state level scores (Figure

2).

Insert Figure 2. CLAS’ conceptual framework.

Finally, recognizing the diversity of curricula in the state and its implementation in local

contexts, CLAS provided for incorporating the uniqueness of classroom instruction into the

assessment system (Figure 1-C). To this end, student artifacts from classroom activities would be

incorporated into a portfolio that sampled these artifacts following a conceptual framework, and

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

14

the classroom teacher would evaluate the portfolio. In this way, immediate feedback was

provided to teachers and students, and the student portfolios could be sampled by the state for use

at multiple levels of the education system.

The classroom-generated test information, scored by the teacher, would then be used by

the state to create a “moderated” score for individual schools and school districts (Figure 2).

Moderation would serve to equate a particular teacher’s scores with the stringency of other

teachers’ scores. In this way, the state would be able to compare scores from one teacher to

another on the “same metric,” and teachers would receive feedback so they could calibrate their

evaluation of student performance with their peers’ evaluations across the state.

The architects of CLAS envisioned a 10-year implementation period (Figure 3). This

was necessary because several new technologies had to be developed. One such technology was

that of alternative assessment including performance assessment. Another new technology, at

least for California, was moderation. California had not tried it before. A third new technology

was combining data from Sources B and C into a state score for schools, districts and the state as

a whole over time. And, finally, the fourth new technology was that of comparing the classroomgenerated information with the on-demand state “audit” in order to see if inconsistencies arose in

classrooms and to reconcile those inconsistencies.

Insert Figure 3. CLAS implementation time line.

CLAS never realized its naïve ten-year implementation time line. Ten years is a political

eternity. And, as it turns out, CLAS ignored Governor Wilson’s political needs and priorities—

an achievement score produced in a timely fashion for each and every student taking the state’s

mandated achievement tests. Moreover, CLAS ran afoul of conservative interest groups in the

State especially in the content used in the literature and writing tests (Kirst & Mazzeo, 1996). As

Governor Wilson wrote to the California Legislature when he red lined the CLAS budget:

SB 1273 [CLAS] takes a different approach . . . . Instead of mandating individual student

scores first, with performance-based assessment incorporated into such scores as this

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

15

method is proven valid and reliable, it mandates performance-based assessment now and

treats the production of individual student scores as if it were the experimental

technology--which it clearly is not. In short, SB 1273 stands the priority for individual

scores on its head.

In spite of its naiveté, CLAS provides a vision of what an accountability system might

look like that links formative and summative assessment. Embedding statewide assessment in

classes to provide a common ground for assessing and comparing achievement has several

virtues. First, it aligns the State’s on-demand, external audit with classroom relevant activities.

Second, it provides immediate feedback to students and teachers, feedback linked not just to the

same class but to peer classes.

And third, classroom assessment is taken seriously and

incorporated into the state-level reporting system. The use of portfolios or other classroom

artifacts, as well, links classroom activities to the state assessment. Moreover, it provides an

opportunity to have local curriculum implementation considered in the assessment of students’

achievement (not unlike the school-based component of the British GCSEs and A-levels).

Another benefit is that CLAS proposed putting part of the state’s assessment responsibility in the

hands of teachers and to provide training and moderation for their professional development.

Finally, the on-demand portion of the system provides a means for immediately auditing

classroom/school scores that are obviously out of line, thereby providing the external

accountability needed for public trust in the testing system.

Task Group on Assessment and Testing: National Curriculum Assessment Results

The Task Group on Assessment and Testing (TGAT) was set up by the UK government

to advise on a new system for national testing at ages 7, 11, 14 and 16 to accompany the first-ever

national curriculum. TGAT proposed the system considered here, developed under severe time

pressures set by the government (from mid-September to Christmas 1987). TGAT issued its

report at the end of December 1987 (“TGAT Report”; DES 1987), with a supplementary report

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

16

(DES, 1988) a few months later including plans for teacher training and for the setting up and

operating a network of local moderation groups.

School assessment practice at the time was generally uncoordinated and ineffective in

providing a clear picture of pupils’ progress, attainment or potential. The brief to the group was to

produce a new scheme, but it was otherwise vague – so TGAT was left free to invent a radically

new system. However TGAT members were aware that there were powerful political groups that

believed that external tests for all, with publication of school performance, were all that was

required. Their report put a different view:

A system which was not closely linked to normal classroom assessments and which

demand the professional skills and commitment of teachers might be less expensive and

simpler to implement, but would be indefensible in that it could set in opposition the

processes of learning, teaching and assessment. (para. 220 D.E.S. 1997).

One basic principle of their scheme was that formative assessment would be the key to

raising standards; they argued that external assessments could only support learning if linked to

formative practice. This meant that both formative and summative assessments had to work to

the same criteria.

Given evidence that pupils' attainments at any one age covered a range corresponding to

several years of normal progression, a second principle proposed by TGAT was that there should

be a single scheme of criteria, spanning across the age-ranges and setting out guidance for

progression in learning. This was accepted and implemented in the specification of the national

curriculum for all subjects: each subject had to specify a sequence of ten criterion-referenced

levels to cover the age range from 5 to 16.

The group also stressed a third principle, that good external tests could be powerful

instruments for raising the quality of teachers' assessments, and recommended that teachers’

assessments should be combined with the results of external tests, with uniformity of standards

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

17

secured through peer review in group moderation.7 Here, the group was able to draw on the

experience of moderation procedures built into external public examination systems in the UK

over many years (see Wood 1991).

However, the group was well aware of the limitations, in validity and reliability, of short

external tests. So they recommended, for example, that the external tests at age 7 be extended

“tasks,” rather like well-designed pieces of teaching which engaged children, and so designed that

they were given opportunity to show performance in the appropriate targets. The general term

Standard Assessment Tasks8 was coined to emphasize that the tests, at all ages, should be

stronger on validity than existing instruments.

TGAT was deeply concerned about the prospect that the government would want too rapid an

introduction of a new scheme. So the report stated:

We recommend that the new assessment should be phased in over a period adequate for

the preparation and trial of new assessment methods, for teacher preparation, and for

pupils to benefit from extensive experience of the new curriculum. We estimate that this

period needs to be at least five years from the promulgation of the relevant attainment

targets.... The phasing should pay regard to the undue stress on teachers, on their schools

and the consequent harm to pupils which will arise if too many novel requirements are

initiated over a short period of time (Section 199, DES 1987).

The overall scheme is represented in Figure 4. It was founded on three operational

recommendations, namely that: (1) the system should be based on a combination of moderated

teachers’ ratings and standardized assessment tasks, (2) group moderation should be an integral

part of the system to produce the agreed combination of moderated teachers’ ratings and the

results of national tests, (3) the final reports on individual pupils to their parents should be the

7

Moderation is UK terminology for a process whereby the assessments of different teachers are put onto a

common scale, whether by mutual agreement between them, or by external audit, or by automatic scaling

using a common reference test.

8

Known as SATs–not to be confused with the meaning in the USA.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

18

responsibility of the teachers, supported by standardized assessment tasks and group moderation

(recommendations 14, 15 and 17 DES 1987), and (4) each subject’s curriculum should be

specified as a profile of about four components, each with its ten levels of criteria, and that

assessment and test results be reported as a profile of the separate scores on each component..

Insert Figure 4: Overview of the TGAT system.

Teachers generally welcomed the report. Prime Minister Thatcher, however, disliked it,

and later wrote:

Ken Baker [Education Minister] warmly welcomed the report. Whether he had read it

properly I do not know: if he had it says much for his stamina. Certainly I had no

opportunity to do so before agreeing to its publication . . .that it was then welcomed by

the Labour party, the National Union of Teachers and the Times Educational Supplement

was enough to confirm for me that its approach was suspect (pp. 594-595 in Thatcher,

1993).

Thatcher’s concern was reflected in the suspicions of some commentators—was this a

Trojan Horse of the right, or a subversion from the left by the “educational establishment?” The

Task Group had not consciously engaged in either maneuver; they were focused on constructing

the optimum system. The suspicions reflect both the simplistic level of public thinking about

testing and the fraught ideological context.

In June 1988, Education Minister Baker announced that he endorsed almost all of the

proposals, including the principle of balance between external tests and teachers' assessments.

However, he found the proposals about the system for managing the implementation of the new

scheme "complicated and costly" – a reservation which left no plan for implementing the

moderation. New proposals were to be worked out by a newly established Schools Examination

and Assessment Council (SEAC).

The subsequent history was of a step-by-step dismemberment of the recommendations

(see Black 1997, Daugherty 1995).

The first casualty was the TGAT vision of Standard

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

19

Assessment Tasks. The trials in 1990 of the first attempts at such tasks attracted considerable and

mainly adverse publicity. The design was modified, but then Baker was replaced. His successor

declared the new tasks to be "elaborate nonsense." A new design was imposed requiring short

‘manageable’ written tests.

The second casualty was teacher assessment. The SEAC paid almost no attention to this

aspect of their brief, perhaps because the priority of setting up the SATs pushed all else off the

agenda, or perhaps because much of the “acceptance” of TGAT was a pretence, to be slowly

abandoned as a different political agenda was implemented. Decisions about the function of

teachers' assessments in relation to the SAT results were changed year by year. Following the

abandonment of moderation the published “league tables” for schools were based on the SATs

results alone. Teachers' assessments, un-calibrated, were to be reported to parents alongside SAT

results, and were later reduced to a formality when it was ruled that teachers could decide their

assessment results after the SATs results were known.

Underlying this history is a struggle for power between competing ideologies.

Conservative policy had long been influenced by fear that left-wing conspiracies seek to

undermine education (Lawton 1994). An example is the following account of the view of

Baker’s predecessor as minister:

Here Joseph shared a view common to all conservative educationists: that education had

seen an unholy alliance of socialists, bureaucrats, planners and Directors of Education

acting against the true interests and wishes of the nation's children and parents by their

imposition on the schools of an ideology (equality of condition) based on utopian dreams

of universal co-operation and brotherhood [Knight, 1990].

Indeed, after Thatcher replaced Baker the TGAT policy was doomed –it was the creature of a

prince who had fallen from favor at court.

However, there remains the question of whether the TGAT plan contained such serious

defects that it was too fragile to survive with or without opposition. Two difficult aspects of the

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

20

scheme were the stress on criterion referencing and the ten-level scheme for progression.

Attempts to implement criterion-referencing in UK public examinations had already run into

difficulty, and the curriculum drafters had little evidence on which to base a scheme of

progression which would match the sequences in which most children achieve proficiency. Both

of these aspects continue to be controversial to the present day (Wiliam 2001) but the national

curricula are still expressed in eight levels of criteria, and everyday school talk involves such

phrases as, “he is working towards level five.” However, the test-level results are only weakly

related to the level criteria.

Another difficulty with the TGAT proposal was the practice of formative and summative

assessment by teachers (Brown, 1989; Swain, 1988). It was known that teachers’ summative

work was of weak quality. Good practice had been established in limited areas, notably in

teacher assessments in English where teacher assessed alternatives to the external examinations

for the school leaving certificates had operated successfully. Various graded assessment schemes

had also set good precedents, although the basis of these was mainly frequent summative testing

conducted by teachers rather than by an integration of formative with summative practices. For

the proposed systems of group moderation however, good practices had been developed and the

TGAT report was able to set out a detailed account of how meetings for peer moderation might

be conducted.

For formative assessment, little was known at the time about either its precise meaning or

about how to develop its potential. The TGAT report said very little about the link between the

formative and summative aspects of teachers’ work and, whilst it listed the various ways that

teachers might collect data, it had little to say about how teachers should make judgments on the

evidence they might collect.

Those responsible for the development of policy understood little about these problems,

their vision being focused on ‘objective’ external tests. Instead of being sensitive to the need for

careful development research to build up the new system, they imposed such speedy

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

21

implementation that the TGAT plan could not survive. Even if the designers had known exactly

how to implement a new scheme, it should have been allowed many more years for development.

Teachers could not in two or three years possibly grasp and incorporate into the complexities of

classroom practice the radically new TGAT plans whilst dealing also with the quite new

curriculum.

But in fact TGAT had faced a dilemma. They knew of - had indeed been involved in –

limited work on all of the components of the new practices they were recommending, but they did

not have time to think through all of the evidence that pertained to their case. The temptation to

produce an acceptable plan meant that they failed to face realistically the full implications of

imposing these practices, in a newly articulated whole, on all teachers. If they had done so, then

perhaps they might have had the courage to declare that at least ten years of careful development

work was essential to translate the proposals into a workable system. If they had stated such a

conclusion, it is almost certain that they would have been dismissed and their report might never

have been published. Ironically, whilst this would have impoverished subsequent debate, it

would probably have made no difference to the eventual outcome.

In spite of its political naiveté, TGAT provides a vision somewhat similar to CLAS of

what a formative-summative assessment system might look like. Such a system would be built to

self-consciously link formative and summative, criterion-referenced assessments to the same set

of standards. As a consequence, teacher assessments would be combined with external tests and

through moderation a combined score and a profile of scores would be reported. Moderation

would provide quality assurance for the classroom data. Formative assessment would take

priority and be a key to raising standards; teachers would be responsible for final reports to

individual student’s parents supported by the standardized test results. This system would take a

developmental perspective where a single set of criteria, spanning across the age ranges, would

set out guidance for progression in learning. The external tests would be extended tasks, not short

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

22

paper-and-pencil tests, similar to well-designed pieces of teaching which would engage students

and would be tied to performance targets.

The Queensland Senior Certificate Examination System

The Queensland Senior Certificate Examination System was designed specifically to

provide formative feedback to teachers and 16-17 year-old college-bound students with the goal

of improving teaching and learning. The examination system was conceived from the very start

to focus on the formative function of assessment and build a summative examination from the

elements of a formative system.

The system was developed in response to an externally

mandated summative system similar to the British A-Level examinations set by the University of

Queensland and later, in transition, by the Board of Senior Secondary Studies.

In 1971, responding to the Radford Committee report (see below), the State of

Queensland, Australia, abolished external examinations and replaced them with a teacherjudgment, criteria-based assessment that students had to pass to earn a Senior Certificate at the

end of secondary schooling. The abolition of the A-level-like external examination was in

response to: (a) “… the recurring tendency for the examinations to be beyond the expectations of

teachers and the capability of students” (Butler, 1995, p. 137), (b) teachers learning all they could

about the senior examiner to anticipate test questions, (c) the absence of formative feedback to

teachers and students, and (d) public dissatisfaction with the process and narrowness of the

curriculum syllabi (Butler, 1995).

In 1970 the Radford Committee recommended abolishing the external examination and

replacing it with a school-based assessment that departed radically from any know assessment of

accomplishment for the Senior Certificate. The Board of Senior Secondary Studies (“Board”)

was to have responsibility for setting the content of the 2-year syllabus in each content area and

the methods of assessing accomplishment.

The system included moderation to establish

comparability of achievement ratings through a Moderation Committee and system of Chief

Moderators.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

23

The “Queensland Experiment” has evolved over the past 30 years and will continue to do

so.

At present it contains two major components. The first component is a school-based

assessment system in each subject area (e.g., science). The school-based assessment system

includes, in each subject area, a locally adapted “course of work” that specifies content and

teaching consistent with the subject syllabus set by the Board and accredited by an external,

government sponsored subject review panel (see Figure 5).

Teachers evaluate (rate) their

students’ performance on the assessment and teachers’ ratings are reviewed through a process of

moderation; the Moderation Committee and Chief Moderators provide external oversight.

The second component of the Queensland system is a general Queensland Core Skills

(QCS) test. The test is used as a statistical bridge for equating ratings across subjects for the

purposes of comparison. If there is a large discrepancy between teacher ratings based on twoyears of work in a subject and the QCS, the former carries the weight, not the latter.

Insert Figure 5. Governance of Queensland’s assessment system.

The assessment system works as follows. A subject syllabus (e.g., in physics) is set by

the Board and covers objectives in four areas: (1) affective (attitudes and values), (2) content

(factual knowledge), (3) process (cognitive abilities), and (4) skills (practical skills). Students are

assessed in the last 3 areas only. The assessment system is criteria and standards referenced, not

norm referenced; student performance is assessed against standards, not against their peers’

performance. The syllabus and assessments are instantiated locally, taking account of local

contexts to link learning to everyday experience, in the form of “school work programs.”9

Teachers rate students according to their level of performance, not to fit a normal curve,

on a 5-point scale: Very High Achievement, High Achievement, Sound Achievement, Limited

Achievement, Very Limited Achievement.

Comparability of curriculum and standards are

“The science teachers in each school are encouraged to write unique work programs guided by the broad

framework in the syllabus document but using all the resources available within the community and

environment surrounding the individual school and taking account of the unique characteristics of students

in the school’ (Butler, 1995, p. 141).

9

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

24

assured through a school-work-program accreditation overseen by State and District Review

panels comprised largely of teachers (about 20% of teachers are engaged in this manner in the

State in each subject). These same panels assure comparability of ratings across the state by

reviewing and certifying each school’s results in each subject area.

The assessment of achievement is formative as well as summative and continuous

throughout the two years of study; students are told which assessments are formative and which

summative (for the purpose of rating their performance on the Levels of Achievement). Each

assessment must clearly specify which criteria and standard it measures and against which a

student’s performance will be judged; students are to receive explicit feedback on each and every

assessment exercise, formative or summative, along with recommended steps for improving their

performance.

The Board is responsible for oversight of the assessment system (see Figure 5), devolving

specific authority to the State and District (subject-matter) Review Panels. The Review Panels

have responsibility for: (a) accreditation—examining a school work program and verifying that it

corresponds to the Board’s syllabus guidelines; (b) monitoring—examining samples of Year 11

student work with tentative Levels of Achievement assigned to check compatibility with criteria

and standards; and (c) certification—of Year 12 Exit Levels of Achievement by insuring

compatibility.

The Queensland system provides a number of lessons in assessment-system design. Built

in response to an externally mandated system that was widely recognized as too difficult for

teachers and students, too narrow and as having undesirable consequences, the present system

focuses on formative assessment with immediate feedback to teachers and students that is linked

to a summative function—the senior certificate. The assessment is continuous over 2 years

providing feedback to students on how to improve their performance from both the formative and

summative examinations. The curriculum (“course of work”) and assessments are developed

locally to external specifications for the content domain (a syllabus) and assessment techniques.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

25

An external, governmental governance structure is in place to assure the public of the credibility

of the course of study, the assessment, and the scores derived from the assessment. And the

assessment focuses on knowledge, cognitive, and practical abilities acquired during the course of

study.

Design Choices

The case studies provide a basis for identifying choices that are made, explicitly or

implicitly, in the design of a large-scale assessment program linking formative and summative

functions.

Here we highlight what appear to be important choices that once made, give

significant direction to the degree of alignment of the summative and formative functions in a

large-scale assessment. To be sure, far more choices are made than represented here and those

choices will ultimately determine whether the alignment produces salutary results; the devil

certainly is in the details.

We have sorted design decisions into a set of related categories; within each category, a

series of choices is made (Table 1). Decisions made in early categories restrict choices later on.

A set of choices across the categories would provide a rough blueprint for an assessment system.

Insert Table 1. Large-Scale Assessment Design Decisions and Choice Alternatives

Purpose

Large-scale assessment systems are meant to serve one or another purpose. Some are

designed to evaluate institutions, others are designed to measure students’ achievement either for

learning improvement (typically formative but see Wood & Schmidt, 2002) or accountability

(typically summative but see especially the Queensland case) while others align assessment for

learning and accountability (as have each of our case studies). At present, the choice alternative,

solely learning-improvement assessment would probably not credibly serve the democratic

purpose of publicly accounting for actions in a shared framework. Consequently we do not view

it as a stand-alone option; the choice set is: PURPOSE = {Accountability, Aligned}.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

26

Accountability Mechanism

We can identify two accountability mechanisms from our case studies: assessment and

audit. The assessment mechanism provides a direct measure of some desired outcome—e.g., an

achievement test. An audit focuses on the processes in place that are necessary to produce

trustworthy information for accountability purposes. It is an indirect measure of some desired

outcome. For formative assessment, the audit would be closely tied to evidence on the quality of

teaching and learning. For summative assessment, the validity and reliability of classroomgenerated information would be of central concern in an audit (and addressed in part by

moderation). While not in place in K-12 education (including CLAS and TGAT), the audit is

used for accountability purposes in higher education in the UK, Sweden, Australia, New Zealand,

and Hong Kong. Queensland uses a combination of local assessment and an audit to insure its

integrity. ACCOUNTABILITY MECHANISM = {Assessment, Audit, Combination}.

Developmental Model

Large-scale assessment might focus on students’ achievement, learning potential, actual

learning or some combination.

Achievement is the declarative, procedural and schematic

knowledge that a student demonstrates at a particular point in time. For example, TIMSS

measured 13 and 14 years old students’ science achievement (“Population 2”).

Learning

potential, beyond achievement, is the amount of support or scaffolding a student needs to achieve

at a level higher than her unaided level. For example, with assistance, a 14-year-old student

might be able to solve force and motion problems that 16 year olds would be expected to solve.

Dynamic assessment of students’ knowledge with teachers interacting with students fits this

focus. Finally, learning is the change or growth from one point in time to another point in time

after intentional or informal instruction and practice. If learning is successively measured by

summative assessments that are conceptually and/or statistically linked to reflect development,

such as TGAT’s Standard Assessment Tasks, the time series can produce ipsative information

and measure individual learning as it develops over time. What is measured, when it is measured,

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

27

and how it is measured depends on whether achievement, learning potential or actual learning is

the focus of the assessment system: DEVELOPMENTAL MODEL = {Achievement, Potential,

Learning}.

Knowledge Tapped

Typically large scale-assessments measure declarative knowledge, mostly facts and

concepts in a domain, and low-level procedural knowledge in the form of algorithms in

mathematics or step-by-step procedures in science. For example, Pine and colleagues found twothirds of the TIMSS Population 2 science test items consisted of factual and simple conceptual

questions (AIR, 2000) with the balance mostly reflecting routine procedures. In measuring

achievement, potential or learning, we identify four types of knowledge, the first two being

declarative and procedural knowledge. The third type of knowledge, schematic knowledge, is,

“knowing why”; for example, “Why does New England have a change of seasons?” Such

knowledge calls for a mental model of the earth-sun relationship that is used to provide an

explanation. The fourth type of knowledge is “strategic knowledge,” knowing when, where and

how knowledge applies in a particular situation. This type of knowledge is required of all even

slightly novel situations regardless of whether the knowledge called for is declarative, procedural

or schematic. So, in the design of an assessment system, a choice needs to be made of the type of

knowledge to be tested: KNOWLEDGE = {Declarative, Procedural, Schematic, Strategic,

Combination}.

Abilities Tapped

As a test relies increasingly on strategic knowledge in bringing forth intellectual

capabilities to solve problems or perform tasks of a relatively novel nature in a subject-matter

domain, it moves away from a strict test of knowledge and increasingly focuses on cognitive

ability (Shavelson & Huang, 2003). These abilities might be crystallized in nature, drawing on

generalization from specific learning to general reasoning in a domain (e.g., reading

comprehension).

The Scholastic Assessment Test taps crystallized verbal and quantitative

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

28

abilities. Or the abilities might be fluid in nature, drawing on abstract representations and selfregulation in completely novel situations. The Raven’s Matrices test is the prototype for fluid

ability. Or, the abilities might require spatial-visual representations that have been generalized

from specific learning situations. Consequently, choices need to be made in the nature of

cognitive abilities to be tapped: ABILITY = {Crystallized, Fluid, Spatial-Visual, Combination}

Balance of Knowledge and Abilities

In designing an assessment system, a choice might need to be made as to the relative

balance between the kinds of knowledge tapped on the test and the kinds of abilities tapped:

BALANCE = {Knowledge, Ability, Combination}.

Curricular Link

An assessment can be linked to curriculum on a rough continuum ranging from very

immediately linked to remotely linked (Ruiz-Primo, Shavelson, Hamilton & Klein, 2002). At the

immediate level, classroom artifacts or embedded assessments (e.g., CLAS) provide achievement

information. At the close level, tests should be curriculum sensitive to the content and activities

engaged in by students (e.g., “embedded” or “end-of-unit” test). At the proximal level, tests

should reflect the knowledge and skills relevant to the curriculum but topics differ from those

directly studied (e.g., Standardized Assessment Tasks). A distal test is based on state or national

standards in a content domain (e.g., National Assessment of Educational Progress Mathematics

Test), and a remote test provides a very general achievement measure (e.g., Third International

Mathematics and Science Study’s Population 2 Science Test). Clearly formative assessments are

typically found at the immediate, close and proximal levels while summative assessments are

found at the proximal, distal and remote levels (but see the Queensland case).

CLAS, TGAT,

and Queensland all envisioned a combination of assessments at various levels. CURRICULAR

LINK = {Immediate, Close, Proximal, Distal, Remote, Combination}.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

29

Information (“Data”) Sources

Achievement information (“data”) can, simply speaking, be collected externally by an

independent data collection agent, internally as a part of classroom activities, or both. Most

larges-scale assessments in the United States such as the National Assessment of Educational

Progress or California’s STAR assessment are conducted externally by an independent agency

(often by a governmental contractor). The British, however, have a tradition of combining

external and internal large-scale assessment including their GCSE, A-level and TGAT

examinations. Indeed, TGAT was envisioned as primarily an internal examination system with

external audits. CLAS, as well, combined external and internal assessment initially with priority

given to external examinations with a shift to internal examinations, as the latter proved feasible.

Finally, the Queensland system is primarily an internal examination system with extensive

governmental oversight and an external examination primarily for cross-subject equating

purposes. INFORMATION SOURCES = {Internal, External, Combination}

Assessment Method

At the most general level, we speak of selected- and constructed-response tests. With

selected-response tests, respondents are asked to select the correct or best answer from a set of

alternatives provided by the tester. Multiple-choice tests are the most popular version, but truefalse and matching tests, for example, would be examples of selected response tests. Such tests

are cost and scoring efficient.

With a constructed-response test, respondents produce a response. Constructed-response

tests range from a simple response (such as fill-in-the-blank), to short-answer, to essay, to

performance assessment (e.g., provide a mini-laboratory and ask a student to perform a scientific

investigation), to concept-maps (students link pairs of key concepts in a domain), to portfolios, to

extended projects. Constructed response, then, is probably too gross a choice but for simplicity,

we lump things together recognizing that this alternative needs unpacking in practice.

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

30

What is important for assessment systems is that the method of testing influences what

can be measured (e.g., Shepard, 2003). For example, performance assessments (envisioned by

both TGAT and CLAS) provide reasonably good measures of procedural and schematic

knowledge but overly costly measures of declarative knowledge. In the design of an assessment

system, then, choices need to be made among possible testing modes and what is to be tested:

TESTING METHOD = {Selected, Constructed, Combination}.

Note that selected methods permit machine scoring whereas constructed response

methods require human (or in a very few cases such as the Graduate Management Admissions

Test, computer) judgment with or without moderation over judges and sometimes, as in the

Queensland case, across subject areas tested.

Test Interpretation

Test scores are typically some linear or non-linear combination of scores on the items that

comprise the test. In and of themselves, they do not have meaning. If we simply tell you that you

received a score of 30 correct, you know little, other than your score was not so low as to be zero

correct! However, you might ask, “How many items were on the test?” Or, you might want to

know, “How did my classmates do on the test?” Or you might want to know, “How much of the

knowledge domain or how many of the performance targets have I learned?” Or, finally, being

very persistent, you might ask, “Did my score improve from the last time I took the test?” Simply

put, a test score needs to be referenced to something to give it meaning.

We distinguish three types of referencing for giving meaning to test scores. The first is

norm or cohort referencing in which individuals are rank ordered and a score comes to have

meaning by knowing the percent of peers who scored below a particular score. For example, the

score of 30 might have been higher that that attained by 90 percent of your peers. The second is

criterion or domain referencing in which a score estimates the amount of knowledge acquired in a

domain. In this case, a score of 30 might mean that from the sample of items, we estimate that

you know about 85 percent of the knowledge domain. And the third type of score reflects

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

31

progression or change over a period of time. We call this an ipsative score and it reflects the

change in the level of your performance in a particular domain.

Test construction and

interpretation depends on the intended meaning or interpretation placed on scores: SCORE

INTERPRETATION = {Norm-referenced, Domain-referenced, Ipsative, Combination}.

Standardization of Administration

Standardization refers to the extent to which the test and testing procedures are the same

for all students. At one extreme, a test is completely standardized when all students receive the

same test, under the same testing condition, at the same time, and so on. This is typically what is

meant by a standardized test. When different test forms are used, we construct those forms to

produce equivalent scores or statistically calibrate them to do so.

Even with different but

equivalent test forms, we speak of the test as standardized. However, at the other extreme, when

tests are adapted to fit each individual, we do not have a standardized test; but the test just might

“fit” the person better than a standardized test. There are a multitude of intermediate conditions.

In building a large-scale assessment, choices about standardization need to be made:

STANDARDIZATION = {High, Intermediate, Low}.

Feedback to Student and Teacher

Feedback from large-scale assessments can be immediate or delayed.

Immediate

feedback occurs, as in TGAT, Queensland and CLAS, when achievement information is collected

in the course of classroom activities (see Information Source above) and is fed back to students

and teachers almost immediately (e.g., teacher evaluates students’ performance using his own or

externally provided rubric). However, most large-scale assessments are conducted externally and

independently where feedback is typically delayed for months. FEEDBACK = {Immediate,

Delayed, Combination}.

If an assessment system is to serve a formative purpose, at least some portion of it must

provide immediate feedback to students and teachers. Moreover, the feedback should advise

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

32

students as to how to improve their achievement, not as scores or other means of ranking students

(Black & Wiliam, 1998; 1998b).

Score Reporting Level

Scores are reported for external accountability purposes, not formative purposes (e.g.,

Black & Wiliam, 1998). To internal audiences such as teachers and parents, information about

individual students is appropriate. For external audiences, scores are reported as aggregates, at

least to the classroom level. When accountability purposes are linked to important life outcomes,

such as reporting scores to the public, attaching teachers’ salaries to them, or certifying that a

student can graduate, high stakes accompanies them. There is some evidence in this case that

summative accountability, although well intended, might very well work against formative

learning purposes (ARG, 2002). SCORE LEVEL = {Individual, Aggregate, Combination}.

Score Comprehensiveness

Single scores are typically reported for accountability purposes. While this satisfies

criteria such as clarity and ease of understanding, single scores that characterize complicated

achievements by students are misleading. For this reason, a score profile—a set of scores linked

to content and knowledge—offers an alternative of more information that is possibly diagnostic

(e.g., Wood & Schmidt, 2002). SCORE-COMPREHENSIVENESS = {Single Score, Score

Profile, Both}.

Application of Design Choices to Case Studies

We now illustrate how design choices (Table 1 above) influence the nature of an

assessment system.

To do so, we characterize the three case studies—CLAS, TGAT, and

Queensland.

California Learning Assessment System

CLAS was designed to align the summative and formative functions of assessment,

providing immediate feedback to teachers and students on classroom embedded tests and

activities, and summative information to the state in the form of an on-demand test to be replaced

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

33

over time by formative information (Table 2). The developmental model underlying the system

was primarily that of achievement—to provide a snapshot of students’ performance at the end of

the school year—with longitudinal aspects associated with embedded tests. The system focused

on knowledge, rather than ability or a balance of the two, especially on declarative and procedural

knowledge with novel parts of the assessment demanding strategic knowledge. To this end, the

testing methods combined selected and constructed response formats, used highly standardized

test administration, and the major method of interpretation was norm-referenced. CLAS was

designed to draw on both internal and external information sources, the former providing

immediate feedback in the form of single scores to students and teachers individually and the later

delayed feedback to educators, parents and students individually, and to policy makers and the

public in the aggregate.

Task Group on Assessment and Testing: National Curriculum Assessment Results

The TGAT design was comprehensive assessment – it was to serve both purposes (Table

2). In particular, the TGAT framework of ten criterion-referenced levels, adopted by those

designing the curriculum documents, could serve the ipsative purposes in providing a longitudinal

picture of development. The reports emphasis on validity, reinforced by use of both external and

teachers’ own assessments, envisaged ways of mapping all four forms of knowledge, up to the

strategic, and combinations of the several dimensions of ability. Similarly, a balance between

knowledge and ability was to be attained by combining both external and internal sources of

assessment information., thereby combining variation in levels of curricular linkage.

For methods, a wide range was envisaged: a 35-page appendix to the report set out 21

examples of assessment items. Only one of these was a selected response item, the others

included test of reading, of oracy involving spoken responses, and practical tasks in science and

mathematics. There was in addition a further six-page appendix describing two extended activity

tasks with seven-year olds, tested in practice, which could have elicited evidence of aspects of

On Aligning Formative and Summative Assessment

34

achievement across a range of subject areas. This diversity reflects the fact that in public tests and

national surveys in the UK the use of selected response items had always been very limited.

The interpretation was to be both ipsative and domain referenced, enhanced by

profile reporting. There was to be a combination of standards to cover a wide range of

the levels at each age. Since the internal (classroom) assessments would be an aggregate

of teachers’ on-going assessments, and the external assessments produced both individual

and aggregated scores, multiple levels were involved.

Finally, scores were to be

assembled in a profile over about three of four domains in each curriculum.

Queensland Senior Certificate Examination System

Queensland aligned the summative and formative functions of assessment giving

priority to the formative function (Table 2). The system provides immediate feedback to

teachers and students on all tests, formative and summative closely linked to the local

curriculum, with advice to individual students on how to improve performance. The

developmental model underlying the system balanced longitudinal and achievement