Education as Development: Poverty and

advertisement

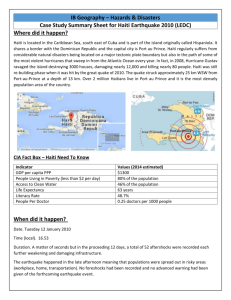

Robinson 1 Education as Development: Poverty and Education in Haiti Sarafina M. Robinson May 4, 2009 Introduction to Poverty Studies Dr. D. Gandolfo and Dr. J. Shelley Robinson 2 Education is development. It creates choices and opportunities for people, reduces the twin burdens of poverty and diseases, and gives a stronger voice in society. For nations it creates a dynamic workforce and well-informed citizens able to compete and cooperate globally – opening doors to economic and social prosperity. -The World Bank Group on the 2000 Millennium Development Goals1 The world in which we live is historically characterized by the interdependency between nations. Not only is our two-thirds world (which constitutes the world’s least developed countries) dependent upon the one-third of developed nations, but there is also interdependency between individual communities, non-governmental agencies, and the like. This particular reliance seeks to promote the general welfare of all people. Additionally, the general welfare of all children is included within the context of relational building between our nations, communities, and non-governmental agencies. Various humanitarian efforts, charitable outreaches, and other related services offer hope to children in desperation. Because children are seen as a precious entity within our global society, their health, access to education and overall well-being are greatly promoted. According to the first Declaration of the Rights of the Child, “The child shall enjoy the benefits of social security. The child must be given the means requisite for its normal development, both materially and spiritually. [And] The child must be brought up in the consciousness that its talents must be devoted to the service of fellow men.” 2 These rights, which were devised during the early twentieth century, call the current state of many children in today’s global society into question. The conditions of children in modernday Haiti, for example, reveal an overall lack of protection and security that is seemingly Robinson 3 guaranteed by the revised Declaration of the Rights of the Child. Kovats-Bernat, author of Sleeping Rough in Port-au-Prince: an Ethnography of Street Children and Violence in Haiti, asserts, “It is axiomatic that children bear the brunt of health and social distress throughout the developing world, and children in least developed countries suffer at a rate consistently higher than those throughout the rest of the world.” 3 Bernat further explains that the combined negative effects on health and social development place a heavier burden on impoverished children of the developing world as compared to those of the developed nations. For example, statistics reveal that infant mortality rates for least-developed countries is nearly twice that for the rest of the world while over four million children in developed countries die before the age of five. Furthermore, thirty-six percent of children under the age of five in least-developed countries are moderately-to-severely underweight.4 Not only do these statistics reveal the harsh realities facing children, but they also reveal the manner in which poverty is perpetuated in the developing world. Living healthy, happily, and productive is a challenge for many people living in destitute nation of Haiti. Abject poverty affects a large portion of the Haitian population, which leaves many if not all of the nation’s citizens devastated by the bleak realities of lacking resources, unstable infrastructures, and insufficient economic earnings. Often times, we think about poverty in relation to varying notions of welfare, homelessness, and the uneven distribution of wealth among social classes. In Haiti, however, the problem of poverty far exceeds such notions of income discrepancies and unjust welfare systems. Instead, Haiti is faced with t one of world’s highest rates of infant mortality, rampant disease that is directly linked to inadequate sanitation Robinson 4 and poor health services, as well as illiteracy rates that exceed those of many other developing nations. Haiti is the fourteenth poorest nation in the world and ranks as the poorest nation in our western hemisphere according to today’s global index. Furthermore, two-thirds of the nation lives at or below the national poverty line, which is defined as subsiding off of two to three dollars per day. Additionally, the GNP per capita is a mere three-hundred eighty dollars. 5 Although the rural population in Haiti is often more subjected to poverty, the entire population is devastated by the harsh realities of scarcity which were originally created by colonialism and later perpetuated by unstable dictatorships, military coups, natural disasters, failing economics, and other related factors threading together the nation’s complex history. Most notable, however, are those specific challenges facing Haitian children. Studies reveal that half of Haiti’s population is under the age of eighteen.6 Much of this constituency faces high mortality rates before the age of five as well as heightened vulnerability to violence and death as displaced and/or orphaned youth both inside and outside the rural and city-limits. According to Save the Children Fund (US), one in nine children is expected to die before the age of nine while a mere fourteen percent of the child population attains access to adequate sanitation facilities on a daily basis.7 Furthermore, 2004 HNP statistics reveal that “the infant morality rate in Haiti is seventy-nine infant deaths per one-thousand live births, the underfive mortality rate is one-hundred twenty three deaths per one-thousand live births, and seventeen percent of children under age of five are severely malnourished.”8 Although some of these rates have seen slight improvements overtime, they still remain high within the broader context of global poverty studies. Robinson 5 Haiti’s underdeveloped educational system is among those factors which reveal the perpetual conditions of poverty in this Caribbean nation. According to the US Aid’s report on Haiti, “The same set of factors which has constrained Haitian development in general, has plagued the education sector as well, resulting in an education system that is ill-equipped to provide quality instruction to the vast majority of Haiti’s children”9 When Haiti gained independence as the first free black nation in 1804, public education was made compulsory. The president of the time, Dessalines—who was the first among many dictators—strived to make those provisions related to compulsory education a reality in Haiti. He went so far as to adapt a non-interventionist model that sought to promote the nation’s new found black identity and ward off the presence of potential imperialist nations within the borders of this newly independent black nation. Dessalines aimed to accomplish these tasks by enacting a violent approach which initiated the onslaught of whites and European descendents within the nation’s borders. Despite Dessalines’ violent non-interventionist policy, some European nations still obtained a lasting presence in Haiti. Today, for example, remnants of France and Britain are actualized through Haiti’s educational system. Haiti’s public education system is modeled after the traditional education structures present in these two European nations. Haiti, nevertheless, has one of the worst-performing education systems in the Americas. 10 The nation struggles to keep track of its educational progress, and its lack of government oversight makes it hard to advance the public and private sectors alike. By 1982, sixty-five percent of the youth population over ten years of age was receiving little to no education while a mere eight percent received education beyond the primary school level.11 Historically, the education system in Haiti was designed to serve the small Haitian elite Robinson 6 whom comprised less than five percent of the total population. This minor constituency attained educational services under the public school system, which was regulated by the government. 11 Conversely, ninety-five percent of the remaining Haitian youth population was either left uneducated or inadequately educated in the small private institutions that lacked any sort of government regulation. The nation’s most recent 1987 Constitution rearticulated the nation’s 1804 commitment to providing a free and compulsory primary education to for all its children. Nonetheless, the nation has yet to put these principles into practice. Today, the primary-school aged children are labeled as the “most vulnerable” individuals in Haiti. After all, a majority of Haiti’s population is between the ages of five and eighteen. Despite increases in foreign aid alongside positive changes in the nation’s political climate with the second democratic election of President Preval, the Haitian educational system significantly lags behind the promises made in 1987 to ensure a free and compulsory education for all its children. Although rates of school enrollment are ever-increasing, the nation still has a long way to go in ensuring that education is universal and the youth are cultivated and prepared for entry into the local and global markets. Nowadays, the recurrent budget for the education system serving nearly two million students totals an estimated at $83 million dollars (or $41 per student). 12 This statistic only includes funding offered to state-sponsored schools; thus, it does not include the amount of privatized money spent on private institutions where most of the children in Haiti are educated. Additionally, the Haitian government spends a mere one percent of its GDP on education. This, in turn, leaves many of the financial ventures to support education up to non-governmental and humanitarian agencies, mission groups, and other forms of foreign aid. While increased funding, more governmental assistance, and local grassroots planning can assist the problems of poverty and education in Haiti, further attention needs to be given to the complexities of poverty as they Robinson 7 relate to the social, political, and economic needs of the country. In doing so, one is able to link the complexities of poverty to the true essence of Haiti’s educational system. Not only does this reveal information about the developing educational system in Haiti, but it also brings into question the level and commitment in promoting youth advocacy and offering opportunities for child agency and social mobility. The expression of child agency in the following song reveals a firsthand account of young people’s desire to promote the general welfare of all children in Haiti. We live in a country; we don’t have freedom of speech. We’re always fighting. We’re not making progress. We are children, just like any other children. God created us. If we are suffering, those in authority, Those with power, Are responsible. 13 This particular song which was written by a group of street children in Port-au-Prince gives a voice to the marginalized youth in Haiti. Though childhood in the Caribbean receives little overall attention as compared to childhood in other global regions, this particular song provides a specific framework for understanding the plea of children who simply desire a better way of life. Not only to these children want to obtain their rights to civil liberties, but they also want to combat issues relating to child mortality, malnutrition, and most importantly—education in Haiti. Robinson 8 Education in Haiti is significantly noted as one among few real opportunities for social advancement. After all children who are exposed to a primary education, at the least, are given opportunities to become literate in a country that is characterized by a fifty-three percentage rate of illiteracy. This, in turn, leads to better attainment of job either abroad or in the nation itself. This fact alone encourages families to place their children in the educational system starting at an early age. The limited availability of public schools and the rising tuition of private institutions, however, make this dream short of reality for many Haitian families. A 1999 UNICEF report stated that the “rising cost of education in Haiti s driving poor families to divert their children into domestic servitude, illicit child labor, or directly onto the street and that is exactly what is happening”14 The estimated cost of private school tuition in Haiti nears that of five U.S. dollars per child per day.15 With an incoming daily allowance of less than one to two dollars a day, however, one can see how the challenge to provide every child with an education (much less a fair and just one) is evident. Thus, it is common to the youngest children of the family attend school while the eldest remain in the domestic sector of familial life. In fact, the most impoverished mothers in the region are often faced with the determinant of sending some of their children to school while sending others to labor in the streets of Haiti’s urban areas where they ultimately find unstable work and “fend for their own welfare in support of the household and their educated siblings” 16 Disparities in Haiti’s educational system are further linked to the growing rift between the availability of public versus private schools. There are approximately 935 public schools and 2031 private primary schools in the region. It is also noted that seventy percent of primary schools in Haiti today are private. Haiti is unique in that it serves a majority of its students Robinson 9 through the private sector of education. According to the Human Development Department of the World Bank, “The Haitian experience is rather unique in a worldwide perspective, especially considering the level of absolute poverty of the country. Of the twenty poorest countries in the world, Haiti is the only one with more than fifty percent of children enrolled in the private sector.” 17 Haiti currently offers seventy-five percent of its youth population educational services through privatized schooling, largely supported by the efforts of the Ministry of Education—a non-governmental agency that provides compensation and aid to teachers and students attending private schools all throughout the nation of Haiti. The problems with private schools, however, are vast. They present even greater complications for those families and children already facing the extreme conditions of poverty of Haiti. For example, private schools are often subject to devastating blows from natural disasters due to their unregulated infrastructures. The 2008 school collapse in Haiti is a tangible example of this reality. The collapse, which resulted in the death of more than one-hundred eighty students, occurred in part because of the failing and unregulated infrastructures of this academic institution. With more government oversight and increased funding to ensure maintenance over these schools, such devastating occurrences could be prevented. Furthermore, the curriculum and teaching staff in Haiti’s privatized sector of education is solely reliant upon the availability (rather than uniformity) of resources in the respective community. The Oxfam Education report, for instance, issued a report stating that private schools for the poor are of “inferior quality,” offering “a low quality service” that will “restrict children’s future opportunities”18 The realities associated with an unmanaged curriculum and teaching staff contribute to the problems relating to educational attainment in the Robinson 10 most rural and remote regions of Haiti. Despite awareness of these issues, rural teachers working in private academic settings often work on a volunteer basis and may not have the level of education standardized by the nation to teach children especially at the primary level. Teachers in the village of Kay Epin for example teach nearly one-hundred students (aged six to eleven) in a poorly built school made from wood slabs and banana leaves. Each teacher has there own limited space (totaling no more than 8 x 8 square feet) where they instruct children using an old French and math curriculum. There resources and classroom materials are paid by humanitarian relief efforts. There salaries, however, are non-existent. In speaking with one of the teachers in this village, he informed me that it only costs $500 US to compensate a teacher in Haiti. There are, however, neither resources nor monies to compensate the six teachers who teach at this small private (mission) school in Kay Epin. Haiti’s educational system is indelibly marked with economic underdevelopment and a system of social stratification that places the highest ranking five percent in the best schools while leaving the majority of Haitian children excluded from exposure to government-regulated and/or formal educational practices. “Because of exclusionary practices that the elite intend to maintain at all costs, unless the state government intervenes, few school-age children have access to quality learning, the only road to prosperity”19 Nowadays, a total of sixty-three percent of the children aged six to twelve are schooled. This percentage fairs high among previous historic accounts; however, the question related to fairness in the educational system is still prevalent. After all, “the education children receive is directly related to where they live and to the level of tuition their families can afford to pay” 20 For instance, the continual increase of the school-age population makes the availability and access to school admission a problem in Haiti. “The increase in school population exacerbates the social and economic cleavages between the poor Robinson 11 and the elite in cities, which in turn magnifies similar divisions within urban schools.”21 Marc E. Prou, author of “Haitian Education under Siege,” suggests that Haiti faces numerous problems that are dominated by high illiteracy rates and “high rates of attrition” in its public education system. 22 Furthermore, the perpetual political instability and failing economics related to the devastations of the agronomist sector in Haiti contribute to the declining conditions in public education system. Additionally, “public schools are not obligated to admit ‘illegitimate’ children and few in fact do, effectively barring any child without proper documents (that is nearly all street children) from matriculating into the school system.”23 Thus, some may argue that private education (though faulty) provides better and more wide-spread opportunities for students in this impoverished nation. In reference to the private schools in Haiti, one cannot help but notice the varying degrees of diversity. Two-thirds of the private schools in Haiti are religious (mission) schools that represent the Catholic, Baptist, Protestant, Adventist, Pentecostal, and Episcopalian denominations.24 These schools receive support from their respective churches, which often receive outside monetary aid from mission groups and churches established in the most developed countries of the West. These schools teach a curriculum that prepares its students for the government administered state-level test that promotes students from primary to secondary school as well as secondary school to institutions of higher education. Additionally, these schools infuse the doctrine of their corresponding faiths into the school curricula. Other private schools are characterized as community and/or commercial schools that receive most of their funding from non-governmental agencies. These agencies are committed to providing opportunities to children who are denied educational access in the public school sector. The Robinson 12 FONHEP (Foundation Haitienne d’Ensignement Prive) for example, provides external funding for teacher training and classroom materials in the private sector. According to the Partnership for Educational Development in the Americas, “The quality [of private schools] is higher than government schools provided for the poor—given that they are predominantly businesses dependent on fee income to survive, and hence accountable to parental needs…By extending what private schools for the poor already offer through free and subsidized places for the poorest, sensitively-applied targeted vouchers could extend access on a larger scale” 25 The current debate over poverty and education in Haiti relates closely to the allocation of funds. Recently, the highest priority of the government has been related to working alongside humanitarian agencies, NGOs, and external donors to improve the educational system in Haiti. More specifically, the past two years has welcomed an increase in political stability and increased foreign aid that is specially channeled to assist the educational ventures of public and private education in this impoverished nation. The United States, for example, currently provides $24 million dollars to support the educational system in Haiti. Furthermore, international agencies and sponsorship programs for the most impoverished children of this nation are dually committed to achieving the 2000 Millennium Goals that seek to provide education for all primary-aged children. The provisions of this goal are to “Ensure that, by 2015, children everywhere, boys and girls alike will be able to complete a full course of primary schooling” by tracking the net enrollment in primary education, the proportion of pupils who complete primary school, and the literacy rates of women and men 15-24 years of age. Though this goal seems highly unattainable in regards to Haiti’s current educational system, it encourages “systemic quality improvement” by retaining as many children as possible in the school system. 26 Robinson 13 Further advances in education and poverty in Haiti are closely related to the creation of new programs that sponsor education for children whose families are unable to afford it. The creation of scholarship programs (similar to those enacted by US Aid) can succeed in providing immediate aid for many children. Nevertheless, the lasting effects of this support could be called into question if unsustainable infrastructures, inadequate teacher bases, and abject poverty that persist and continue to disenfranchise those school children receiving sponsorships in Haiti. Addressing the problems of poverty and education in Haiti is complex. Some solutions relate to the increased aid from outside agencies while others relate to the reallocation of government funds to support public education. A vital component in the consideration of each of these suggestions relates to the specific needs of the Haitian youth who are most affected by shifts in policies and changes in structure. Educational transformation is not simply a matter of monetary reallocation. Instead, “The notion of educational transformation involves the democratization of the pedagogical and educational power so that students, staff, teacher, educational specialists, and parents come together to develop a plan that is grassroots generated…”It is imperative, therefore, that the government and humanitarian agencies alike work to provide opportunities for pedagogical and educational empowerment not only among the students, but also among the school personnel in Haiti. This works to ensure that education does, indeed, “create choices and opportunities for people, reduce the twin burdens of poverty and diseases, and give a stronger voice in society.” This in turn has the potential to “open doors to economic and social prosperity” that will aid in the future development of Haiti—our poorest neighbor. 27 Robinson 14 1. The World Bank Group, The Millennium Development Goals (United Nations) http://www.moe.gov.pk/MDGs/Millennium%20Development%20Goals%20Education.htm. (September 2004). 2. International Union for Child Welfare, Declaration on the Rights of the Child: Principle 5, 1923. 3. Bernat-Kovats, Christopher J. Sleeping Rough in Port-au-Prince: An Ethnography of Street Children and Violence in Haiti. University Press of Florida: Gainesville. 2006. 4. UNICEF Press Release. “Survival is Greatest Challenge for Haiti’s Children.” 2005. 5. Sloland, Elizabeth and Bette Gerbian. “Fathers Clubs to Improve Child Health in Rural Haiti,” (Public Health Nursing Vol. 23 No. 1) 47. 6. Sloland, Elizabeth and Bette Gerbian. “Fathers Clubs to Improve Child Health in Rural Haiti,” (Public Health Nursing Vol. 23 No. 1) 50. 7. UNICEF Press Release. “Survival is Greatest Challenge for Haiti’s Children.” 2005. 8. Sloland, Elizabeth and Bette Gerbian. “Fathers Clubs to Improve Child Health in Rural Haiti,” (Public Health Nursing Vol. 23 No. 1) 51. 9. Anderson, Jennifer R., “A Country’s Hope: The Haiti Scholarship Program,” (USAID| Haiti: American Institutes of Research, Washington, DC 2007) 2. 10. Wolff, Laurence. “Education in Haiti: The Way Forward,” Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas. 3. 11. US Library of Congress. “Haiti: Education.” April 2009. http://countrystudies.us/haiti/36.htm 12. Wolff, Laurence. “Education in Haiti: The Way Forward,” (Education in Haiti Today. Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas) 3. 13. Bernat-Kovats, Christopher J. Sleeping Rough in Port-au-Prince: An Ethnography of Street Children and Violence in Haiti. (University Press of Florida: Gainesville. 2006) 47. 14. qtd in Bernat-Kovats, Christopher J. Sleeping Rough in Port-au-Prince: An Ethnography of Street Children and Violence in Haiti. (University Press of Florida: Gainesville. 2006) 49. 15. Salmi, Jamil. “Equality and Quality in Private Education: The Haitian Paradox” (The World Bank: Latin America and Caribbean Regional Office, Human Development Department LCSH Paper Seriece No.18 May 1998) 5. 16. Bernat-Kovats, Christopher J. Sleeping Rough in Port-au-Prince: An Ethnography of Street Children and Violence in Haiti. (University Press of Florida: Gainesville. 2006) 51. 17. Rotberg, Robert I. Haiti Renewed: Political and Economic Prospects. (Brookings Institution Press: Washington, D.C., 1997). 18. qtd. in“Educating Amaretch: Private Schools for the Poor and the New Frontier for Investors” (Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas, 2008) 2. 19. Rotberg, Robert I. Haiti Renewed: Political and Economic Prospects. (Brookings Institution Press: Washington, D.C., 1997). 20. Rotberg, Robert I. Haiti Renewed: Political and Economic Prospects. (Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC., 1997). 21. Hugonnier, Bernard. “Globalization and Education: Can the World Meet the Challenge?” (ed. By SuzrezOrozco, Marcelo, Leaning in the Global Era. University of California Press, 2007) 139. 22. “Haitian Education under Siege: Democratization, National Development and Social Reconstruction,” in Robert I. Rotberg (Eds.), Haiti Renewed: Political and Economic Prospects (Brookings Institute Publications, 1997), 215-228. 23. Bernat-Kovats, Christopher J. Sleeping Rough in Port-au-Prince: An Ethnography of Street Children and Violence in Haiti. (University Press of Florida: Gainesville. 2006) 48. 24. Salmi, Jamil. “Equality and Quality in Private Education: The Haitian Paradox” (The World Bank: Latin America and Caribbean Regional Office, Human Development Department LCSH Paper Seriece No.18 May 1998) 5. 25. “Educating Amaretch: Private Schools for the Poor and the New Frontier for Investors” (Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas, 2008) 2. 26. The World Bank Group, The Millennium Development Goals (United Nations) http://www.moe.gov.pk/MDGs/Millennium%20Development%20Goals%20Education.htm. (September 2004). Robinson 15 27. The World Bank Group, The Millennium Development Goals (United Nations) http://www.moe.gov.pk/MDGs/Millennium%20Development%20Goals%20Education.htm. (September 2004). Works Cited Anderson, Jennifer R. U.S. Aid: Haiti. “A Country’s Hope: The Haiti Scholarship Program,” 2007. Washington DC: American Institutes for Research. “Educating Amaretch: Private Schools for the Poor and the New Frontier for Investors” Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas: 2008, p 2. “Haitian Education under Siege: Democratization, National Development and Social Reconstruction,” in Robert I. Rotberg (Eds.), Haiti Renewed: Political and Economic Prospects (Brookings Institute Publications, 1997), 215-228. Hugonnier, Bernard. “Globalization and Education: Can the World Meet the Challenge?” (ed. By Suzrez-Orozco, Marcelo, Leaning in the Global Era. University of California Press, 2007) 139. International Union for Child Welfare, Declaration on the Rights of the Child: Principle 5, 1923. Kovats-Bernat. Sleeping Rough in Port-au-Prince: An Ethnography of Street Children and Violence in Haiti. 2006. University Press of Florida. Rotberg, Robert I. (ed.) Haiti Renewed: Political and Economic Prospects. 1997. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. Salmi, Jamil. “Equality and Quality in Private Education: The Haitian Paradox,” The World Bank: Latin America and Caribbean Regional Office, Human Development Department LCSH Paper Seriece No.18 May 1998, p 5. Sloland, Elizabeth and Bette Gerbian. “Fathers Clubs to Improve Child Health in Rural Haiti,” (Public Health Nursing Vol. 23 No. 1, p 51. The World Bank Group. “The Millennium Development Goals: United Nations” September 2004.http://www.moe.gov.pk/MDGs/Millennium%20Development%20Goals%20Education .htm. UNICEF Press Release. “Survival is Greatest Challenge for Haiti’s Children.” 2005. US Library of Congress. “Haiti: Education.” April 2009. http://countrystudies.us/haiti/36.htm. Wolff, Laurence. “Education in Haiti: The Way Forward,” Education in Haiti Today: Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas, p 3. Robinson 16