Dang - California State University, Fresno

advertisement

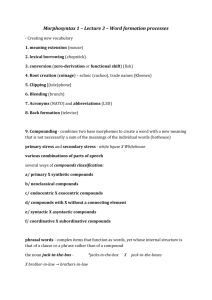

ABSTRACT DOES PROSODIC WORD RECURSION CAUSE PHONETIC INITIAL STRENGTHENING? The paper is the very first study to address the issue of domain-initial strengthening in recursive prosodic words. Domain-initial strengthening concerns the articulatory strength of segments at the left edges of prosodic domains. The widely-used scale of prosodic positions is the prosodic hierarchy. The current study employs a different scale, i.e., recursive prosodic words in which smaller prosodic words are recursively embedded in a larger word. The length of /s/ is measured when it is placed in the initial positions of 2-, 3- and 4-word Vietnamese noun compounds in order to investigate whether prosodic word recursion causes articulatory strengthening. The findings show that there is no significant duration difference among the domains of recursive prosodic words, which reflects no strengthening effect of prosodic recursion on segmental articulation. Therefore, domain-initial strengthening appears to be sensitive to the categories of prosodic constituents rather than the depth of their embedding. Key words: domain-initial strengthening, prosodic word recursion Phuong Hoai Dang May 2013 DOES PROSODIC WORD RECURSION CAUSE PHONETIC INITIAL STRENGTHENING? by Phuong Hoai Dang A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Linguistics in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2013 APPROVED For the Department of Linguistics: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Phuong Hoai Dang Thesis Author Chris Golston (Chair) Linguistics Brian Agbayani Linguistics Sean Fulop Linguistics For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS x I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship. Permission to reproduce this thesis in part or in its entirety must be obtained from me. Signature of thesis author: ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis supervisor Chris Golston and committee members Brian Agbayani and Sean Fulop for their devoted support, invaluable guidance and constructive feedback during the preparation and completion of the thesis. I would like to send my special thank to Thuong Bui and Duc Dang for their indispensable help in the process of data collection. I also owe a big debt to the participants in the current thesis. I could not have completed the thesis without their patient and devoted participation. Last but not least, I am indebted to my family who always give me encouragement and support towards the completion of the thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................. vi LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................ vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 1 1.1 Domain-initial strengthening ...................................................................... 1 1.2 Prosodic recursion ....................................................................................... 3 1.3 The current study......................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 2: NOUN COMPOUNDS IN VIETNAMESE ..................................... 8 2.1 Description .................................................................................................. 8 2.2 Prosodic organization ................................................................................ 14 CHAPTER 3: METHODS ..................................................................................... 16 3.1 Prosodic domains ...................................................................................... 16 3.2 Participants ................................................................................................ 17 3.3 Materials .................................................................................................... 17 3.4 Data collection procedures ........................................................................ 19 3.5 Data analysis procedures ........................................................................... 20 CHAPTER 4: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ..................................................... 21 4.1 Results ....................................................................................................... 21 4.2 Discussion ................................................................................................. 22 CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION ............................................................................... 25 REFERENCES ....................................................................................................... 27 APPENDICES ........................................................................................................ 32 APPENDIX A: VIETNAMESE NOUN COMPOUNDS ...................................... 33 LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Speech materials for the study ................................................................. 18 Table 2. Variation across compounds and speakers ............................................... 23 LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1. Prosodic organization of 2-, 3- and 4-noun compounds ......................... 15 Figure 2. The waveform and spectrogram of the compound mui sɛ ‘car roof’ ...... 20 Figure 3. Mean /s/ duration for all speakers ........................................................... 21 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Domain-initial strengthening It has been observed that the phonetic properties of segments vary according to their positions in the prosodic structure of languages thanks to a wide range of research regarding the interaction between prosody and segmental articulation. French consonants and vowels have greater amplitude and duration in stressed syllables than in unstressed syllables. English /s/ seems to have less aspiration noise in the middle of Word than at the beginning of Word and Intonational Phrase. There is an increase in the Voice Onset Time of Korean aspirated consonants from Word-medial positions to Word-initial positions to Accentual Phrase-initial positions (see Fougeron 1999 for a review). The examples above are only a few out of different studies on the effect of prosodic positions on phonetic segments which is called prosodic strengthening. Cho (2005: 3867) defines prosodic strengthening as “temporal and/ or spatial expansion of articulation due to accent and/ or prosodic boundaries” and mentions the three socalled strong prosodic positions are the left edges of prosodic domains, the right edges of prosodic domains and accented syllables. One line of prosodic strengthening research is domain-initial strengthening which concerns “prosodic strengthening associated with left edges of prosodic domains” (Cho et al. 2007: 211). Trask (1996) defines “strengthening” as “a phonological process in which some segment becomes stronger.” The widely used scale of prosodic positions for domain-initial strengthening is the prosodic hierarchy which is a hierarchically organized structure of prosodic domains such as Utterance, Intonational Phrase, Phonological Phrase, Word, Syllable, etc. (Selkirk 1978; Selkirk 1984; Nespor & Vogel 1986; see Selkirk 1995; Selkirk 2 2009 for a review). In general, domain-initial strengthening is a phonological process in which segments at the left edges of higher prosodic constituents are articulatorily stronger than those at the left edges of lower prosodic constituents. The phenomenon of domain-initial strengthening has been investigated in different languages such as English (Fougeron & Keating 1996; Keating et al. 1999), Taiwanese (Hsu & Jun 1998; Hayashi et al. 1999; Keating et al. 1999), Korean (Keating et al. 1999; Cho & Keating 2001), French (Keating et al. 1999; Fougeron 2001), German (Kuzla et al. 2007; Kuzla & Ernestus 2011), and Arabic (Al Taisan 2011). These studies generally explore two research questions. The first concerns how the organization of prosodic constituents affects the articulation of speech segments, and the second examines whether the articulatory variation of segments at the beginning of prosodic domains can help mark the prosodic hierarchy of a language. The common measurements are linguopalatal contact and segment duration. Some acoustic parameters are also used in the domain-initial strengthening studies; however, the results concerning them and their correlations with linguopalatal contact or segment duration are not consistent to reflect the general picture of domain-initial strengthening. On the one hand, Fougeron and Keating (1996) do not find any strong correlations between linguopalatal contact and acoustic measurements like VOT, vowel duration and stop burst energy for the English nasal /n/; Hsu and Jun (1998) and Hayashi et al. (1999) see that there is no significant effect of prosodic positions on VOT duration of the investigated stops in Taiwanese. On the other hand, Cho and Keating (2001) find that the acoustic measurements like stop closure duration, VOT, Total Voiceless Interval, % voicing during closure, vowel duration, stop burst energy, nasal duration and 3 nasal energy vary according to the prosodic positions of the four tested Korean stops and some of them have correlations with linguopalatal contact; Kuzla and Ernestus (2011) find that /b/, /d/, and /g/ have less glottal vibration and /p/, /t/, /k/ have shorter VOT duration after higher prosodic boundaries in German. The general finding is that speech segments in higher prosodic domains have more linguopalatal contact and/or longer duration than those in lower domains; and the increase of segmental articulation from the lowest to highest domain is usually cumulative. The found pattern of domain-initial strengthening, on the one hand, reflects the effect of prosodic organization on phonetic articulation, on the other hand, provides articulatory and/or acoustic cues to distinguish prosodic boundaries. Note that the findings of domain-initial strengthening show certain variation across languages, segments, speakers, and prosodic domains. For instance, Cho and Keating (2001:185) observe that Korean has a clearer and more consistent picture of domain-initial strengthening than English, French, and Taiwanese. Regarding the variation across segments, Fougeron (2001:119) sees that “/s/ is less systematically affected by prosodic position compared to the other consonants studied like stops and /l/.” Furthermore, it is observed that not all speakers distinguish all prosodic domains. Fougeron and Keating (1996) report two speakers make distinction among three levels while the other speaker distinguishes only two. In the study which compares domain-initial strengthening in four languages, Keating et al. (1999) also discuss that all speakers make at least two domains distinct, which is robust in the findings. 1.2 Prosodic recursion In the discussion of prosodic recursion, it is crucial to mention the Prosodic Hierarchy Theory proposed by Selkirk (1978) and developed by Selkirk (1984) 4 and Nespor and Vogel (1986) (see Selkirk 1995; Selkirk 2009 for a review). The theory claims that a string of speech in a language can be exhaustively parsed into different prosodic constituents in which higher domains contain lower ones. (1) The Prosodic Hierarchy (Selkirk 1995: 5) Utt Utterance IP Intonational Phrase PhP Phonological Phrase PWd Prosodic Word Ft Foot σ Syllable There is a set of constraints on prosodic domination which characterizes the features of the prosodic hierarchy. Specifically, the two constraints of Layeredness and Headedness claim that speech in every language is hierarchically organized in prosodic constituents; higher-ranked constituents dominate lower-ranked constituents. In a stricter sense, the constraints of Exhaustivity and Non-recursivity require that every higher domain must dominate or must be completely parsed into immediate lower domains, which means that there is no level skipping or repetition at any prosodic domain. The first two constraints are inviolable and undominated thanks to the observation that every language has several prosodic levels. On the other hand, it has been argued that Exhaustivity and Non-recursivity are violable and low-ranked because certain prosodic levels are found to be skipped or recurred in a number of languages (Selkirk 1995; Ito & Mester 2009). In sum, the violability and low ranking of Exhaustivity and Non-recursivity result in prosodic skipping and recursion. 5 Prosodic recursion refers to the repetition of prosodic domains at a certain level of the prosodic structure. Specifically, prosodic recursion involves the embedding of a prosodic domain of a certain level in another prosodic domain of the same level; the larger domains contain the smaller ones (Inkelas 1990; Selkirk 1995; Ito & Mester 2008; Ito & Mester 2009; Kabak & Revithiadou 2009; Selkirk 2009; Féry 2010). Furthermore, it is observed that compound structures are frequently exemplified as prosodic recursion thanks to the notion that the compound structures as well as their components belong to the same category and the compounds are larger constituents containing their smaller components (Ladd 1990; Ladd 1996; Inkelas 1990; Green 2007; Kabak & Revithiadou 2009). 1.3 The current study As mentioned above, domain-initial strengthening, a type of prosodic strengthening concerning the articulatory strength of segments at the left edges of prosodic constituents has been explored in a wide range of research in which the currently-employed scale of prosodic positions is the prosodic hierarchy of languages. It is interesting to revisit this phenomenon with a different prosodic scale. Particularly, the current study investigates the articulation of phonetic segments in the initial positions of prosodic domains of the same level called recursive prosodic words. The study is the first to examine the interaction between prosodic recursion and segmental articulation. More specifically, the paper addresses the issue of domain-initial strengthening in recursive prosodic words. Prosodic recursion involves the containment of smaller constituents inside a larger constituent of the same category; therefore, the formation of recursive prosodic words concerns the embedding of smaller prosodic words in a larger prosodic word. Compounds in 6 languages are argued to be recursive prosodic words (Inkelas 1990; Green 2007; Kabak & Revithiadou 2009). The studied case is Vietnamese noun compounds. Vietnamese is a tonal monosyllabic language in which syllables are argued to be the smallest units of phonological and morphological analysis (Ngo 1984; Nguyen 2011). Particularly, Ngo (1984) proposes the notion of “syllabeme” is the minimal grammatical unit in Vietnamese; it can function as a syllable, a morpheme and a word. Nguyen (2011) argues that a word in Vietnamese is a minimal meaningful unit whose spoken form is a syllable and written form is a separate group of letters. A compound in Vietnamese can be comprised of two or more elements; each is a one-syllable word; and the compounding of these monosyllabic elements creates a new lexical item. Therefore, Vietnamese compounds are appropriate candidates for the notion of recursive prosodic words thanks to the fact that the whole compounds are larger prosodic words which are constituted by smaller prosodic words. In order to investigate the articulatory variation across initial positions of recursive prosodic words, the duration of the voiceless alveolar fricative /s/ is measured when it is at the beginning of each monosyllabic word of 2-, 3-, and 4word noun compounds. The two possibilities are hypothesized towards the findings of the study. First, there is a cumulative increase of segmental length from the smallest to the largest constituent-initial positions, which reflects the significant role of the embedding of smaller prosodic words in larger prosodic words. Second, there is no strong distinction among the domains of recursive prosodic words, which implies the effect of prosodic categories on domain-initial strengthening. 7 Generally speaking, the study aims at exploring the phenomenon of domain-initial strengthening with the scale of recursive prosodic words. /s/ is placed in the initial positions of 2-, 3-, and 4-word compounds and its duration is measured to examine whether prosodic word recursion causes articulatory strengthening. 8 CHAPTER 2: NOUN COMPOUNDS IN VIETNAMESE 2.1 Description1 Compounding is the word formation process which involves the combination of existing words to build new lexical items. Vietnamese compounds are formed under such the process; two or more monosyllabic words are combined to generate a single category. There are three word types of compounds in Vietnamese: compound nouns, verbs and adjectives; each of them is classified into two subtypes including coordinate and subordinate compounds. Coordinate compounds involve the compounding of two or more words in which “each constituent is a center” and “occurs in juxtaposition” (Nguyen 1997:66). Semantically, they are called generalizing compounds because the meanings of the two centers are combined to form a more general lexical item. These centers belong to the same category or are synonyms or antonyms. (1) a. bàn ɣé table chair ‘furniture’ b. muə bán buy sell ‘buy and sell’ c. cɑ̉i cuót brush polish ‘be meticulous’ 1 See more examples of Vietnamese noun compounds in Appendix A. 9 Subordinate compounds concern the combination of the words with the head-complement order. The heads are more general lexical items or concepts and the complements modify and narrow the meanings of the heads. Subordinate compounds refer to more specific lexical items and then are called specializing compounds. (2) a. nɯɤ́k dɑ́ water ice ‘ice’ b. làm ruọŋ do rice field ‘do farming’ c. sɛ lɯ̉ə vehicle fire ‘train’ More specifically, coordinate noun compounds involve the combination of nouns and their meanings reflect the generic category of the constituent nouns. The examples in (3), (4) and (5) exemplify the 2-word, 3-word and 4-word noun coordinate compounds respectively. Note that 3-word coordinate compounds are not as popular as the other two. (3) a. cim muoŋ bird beast ‘animals’ b. rau kɔ̉ vegetable grass ‘veggies’ c. ruo͎ŋ nɯɤŋ 10 wet field dry field ‘cultivated fields’ d. ruòi muõi fly mosquito ‘flies/ bugs’ e. kwʌ̀n Ɂɑ́u pant coat ‘clothes’ (4) a. vɯɤ̀n Ɂɑu cuòŋ garden pond shed ‘traditional Vietnamese farm’ b. Ɂaɲ cị Ɂɛm brother sister younger sibling ‘brothers and sisters’ c. ræŋ hàm mæ͎t tooth jaw face ‘the medical study of teeth, jaws and face’ d. tai mũi hɔ͎ŋ ear nose throat ‘the medical study of ears, noses and throats’ (5) a. bɑ̀ kɔn ko grandmother child aunt bák uncle ‘relatives’ b. sɤn hɑ̀ sɑ̃ mountain river village principle ‘country’ tǽk 11 c. soŋ nɯɤ́k nɔn núi river mountain water mountain ‘country’ d. zɯɤ̀ŋ tủ bàn bed table chair wardrobe ɣé ‘furniture’ e. maj lan apricot orchid kúk ʈúk chrysanthemum bamboo ‘set of four symbolic flowers and plants’ Subordinate noun compounds involve the combination of heads and complements in which the complements follow and modify the heads. Regarding 2-word subordinate compounds, Nguyen (1997) observes that there are the three combinations; the heads are always nouns whereas the complements can be nouns, verbs and adjectives. The examples in (6) exemplify the 2-word subordinate compounds which involve the three types of noun compounding such as a noun and a noun (6a-b), a noun and a verb (6c-d) as well as a noun and an adjective (6ef). (13) a. bɔ̀ kɔn cow/ox child ‘calf’ b. kɤm ɣɑ̀ rice chicken ‘chicken rice’ c. sɛ dạp vehicle to pedal ‘bike’ 12 d. kɤm nǽm rice to wisp ‘rice ball’ e. bɔ̀ dɯ͎k cow/ox male ‘ox’ f. bɔ̀ kái cow/ox female ‘cow’ The examples in (7) and (8) are 3-word and 4-word compounds in which the heads are left-edged. (7) a. dɯɤ̀ŋ cʌn ʈɤ̀i line sky foot ‘horizon’ b. báɲ sɛ bɔ̀ wheel vehicle cow/ox ‘cow/ox cart wheel’ c. bụi than dɑ́ dust coal stone ‘coal dust’ d. vụn báɲ mì crust cake wheat ‘bread crust’ e. kỏ Ɂɑ́u neck blouse suit ‘suit collar’ vét (8) a. vɔ̉ bark thʌn kʌi body tree dɑ banyan ‘banyan tree bark’ b. duoi kɑ́ nɯɤ́k mæ͎n tail water salty fish ‘sea water fish tail’ c. thʌn kʌi body tree kɑ̀ cuə eggplant sour ‘tomato tree body’ d. vɔ̉ báɲ sɛ bɔ̀ tire wheel vehicle cow/ox ‘cow/ox cart wheel tire’ e. kiẻu kỏ Ɂɑ́u vét model collar blouse suit ‘suit collar model’ Another type of 4-word subordinate compounds is also found to be popular in Vietnamese; they involve the combination of two 2-word subordinate compounds, as seen in (9). (9) a. bén station sɛ mièn doŋ car region east ‘Eastern station’ b. bɯ́k tɯɤ̀ŋ Ɂʌm thaɲ piece wall audio sound ‘sound wall’ c. bài thɤ tìɲ Ɂieu 14 piece poem sentiment love ‘love poem’ d. vɔ̀i nɯɤ́k bòn tǽm faucet water tub bath ‘bathtub tap’ e. Ɂóŋ bɤm sɛ pipe pump vehicle dạp bike ‘bike pump’ 2.2 Prosodic organization Vietnamese noun compounds are recursive prosodic words; the whole compounds are the largest word constituents which contain smaller word constituents. In the current study, 2-, 3- and 4-word coordinate and subordinate compounds are investigated. The prosodic organizations of these compounds are presented in (10). Coordinate and subordinate compounds are abbreviated as ‘CC’ and ‘SC’, respectively. (10) Prosodic organizations of 2-, 3- and 4-word compounds 2-word SC (word (word)) 2-word CC (word (word)) 3-word SC (word (word (word))) 4-word SC with left-edged heads (word (word (word (word))) 4-word SC of two 2-word SCs (word (word)) (word (word)) 4-word CC (word (word)) (word (word)) The diagrams in Figure 1 provide a clearer picture of the prosodic organizations of the compounds. The arrows below the transcriptions display the meaning relation among the words; the single arrows refer to the head- 15 complement relation and the double arrows refer to the equal relation between two words. 2-word SC 2-word CC 3-word SC 4-word SC of two 24-word CC 4-word SC with leftword SCs edged heads Figure 1. Prosodic organization of 2-, 3- and 4-word noun compounds CHAPTER 3: METHODS 3.1 Prosodic domains The paper addresses the issue of domain-initial strengthening in recursive prosodic words. The studied case is the length variation of /s/ in the initial positions of each word of Vietnamese noun compounds which are recursive prosodic words in which the whole compounds are larger word constituents and component words are recursively embedded smaller constituents. 2-, 3- and 4word noun compounds are speech materials; therefore, the tested domains are the left edges of each word of these compounds. They are coded as W1i, W2i, W3i and W4i which refer to the initial positions of the words in the compounds; for instance, W1i corresponds to the initial position of the first word in the compounds. Recalling the prosodic organization of these compounds in Section 2.2, for all compounds, the leftmost edge is the largest word boundary where the edge of the whole compounds coincides with that of the first word; the smaller boundaries are those of component words embedded inside the compounds; and the smallest is the left edge of the last word. Particularly, in 2-word compounds, the W1i position is the largest word boundary; and the W2i the smallest. In 3-word compounds, the W1i position is the largest; the W2i the second largest; and the W3i the smallest. In 4-word subordinate compounds with left-edged heads, the word boundaries progressively decrease from the W1i position to the W4i position. In 4-word subordinate compounds of two 2-word subordinate compounds, the W1i position is the largest, the W3i the second largest, the W2i the third largest, and the W4i the smallest. In 4-word coordinate compounds, the 17 W1i position is the largest, the W3i the second largest, and the W2i and W4i the smallest. 3.2 Participants Ten speakers, five males and five females, participate in the study. These participants are native speakers of Vietnamese; they all speak the Southern dialect. Among the ten speakers, four live in Ben Tre City and six live in Ho Chi Minh City; these two cities locate in South Vietnam where the Southern dialect is mainly spoken. The age of the participants ranges from 18 to 53. All of the speakers are literate and have no speech problems. 3.3 Materials The investigated speech segment is /s/, which is chosen thanks to the ease of recognition and measurement. It is placed in the initial position of each word noun compounds. It is surrounded by sonorants like nasals and vowels. Also, the carrier word of the segment is kept the same for each set of the target compounds so as to avoid the impact of other sounds on the segment if any. The tested environments are coordinate and subordinate noun compounds. Regarding coordinate compounds, 2- and 4-word compounds are under investigation due to the fact that the small number of the 3-word compounds in the language does not provide sufficient environments containing the target speech segment. In addition to 2-, 3- and 4-word left-headed compounds, 4-word compounds composed of two 2-word subordinate compounds are also employed. All of the investigated positions are at the word domain of the prosodic hierarchy but in different word constituents of recursive PWs from the largest to the smallest. /s/ is placed in the initial positions of the first and second words in 2word compounds, in those of the first, second and third words in 3-word compounds or in those of the first, second, third and fourth words in 4-word 18 compounds. Then the compounds are embedded in the same carrier sentence (e.g. læ͎p la͎i sɛ hɤi bɑ lʌ̀n ‘Repeat car three times’). Table 1 below presents the speech materials used in the study and illustrates the descriptions concerning the speech segment /s/, the tested environments of Vietnamese noun compounds and the investigated domains of recursive prosodic words. Table 1. Speech materials for the study Subordinate compounds hɤi 2-word compounds sɛ soŋ núi vehicle car river mountain ‘car’ ‘the whole country’ mui sɛ núi roof vehicle mountain river ‘car roof’ ‘the whole country bɑ 3-word compounds sɛ báɲ vehicle three wheel ‘three-wheeled cart’ hɤi mui sɛ roof vehicle gas ‘car roof’ vɔ̉ báɲ sɛ tire wheel vehicle ‘bike/motorbike/car tire’ 4-word compounds sɛ with heads Coordinate compounds hòŋ thʌ͎p tɯ͎ left-edged vehicle red cross word ‘ambulance’ mui sɛ Ɂo to soŋ 19 roof vehicle auto ‘car roof’ vɔ̉ báɲ hɤi sɛ tire wheel vehicle gas ‘car tire’ màu vɔ̉ báɲ sɛ color tire wheel vehicle ‘vehicle tire color’ hɤi dò 4-word compounds sɛ of two compounds cɤi 2-word vehicle gas thing play ‘toy car’ vɔ̉ sɛ soŋ núi bɤ̀ kɔĩ river mountain bank region ‘the whole country’ dò cɤi nɔn soŋ dʌ́t nɯɤ́k tire vehicle thing play mountain river earth water ‘toy car tire’ ‘the whole country’ kʌu cwie͎n sɛ dạp bɤ̀ kɔĩ soŋ núi fish story vehicle bike bank region river mountain ‘bike story’ ‘the whole country’ kʌu cwie͎n vɔ̉ sɛ bɤ̀ kɔ̃i núi soŋ fish story tire vehicle bank region mountain river ‘tire story’ ‘the whole country’ 3.4 Data collection procedures The speakers were given the list of 19 Vietnamese noun compounds like those in Table 1 above. They were asked to read through these compounds and explained that they were going to read them aloud as naturally as possible, each compound was repeated three times, and their speech was recorded individually. 570 speech tokens (19 compounds x 3 repetitions x 10 speakers) were recorded and analyzed in the study. 20 3.5 Data analysis procedures Two criteria are used to define the segment length. First, /s/ is a fricative, which means that its large acoustic energy is distributed at a high frequency. The view range of the spectrograms is adjusted to be as high as 10000 Hz in order that such energy is clearly observed. Second, /s/ is a voiceless sound and, as mentioned in Section 3.3, it is surrounded by nasals and vowels, which implies the absence of the pitch line on the spectrograms. Figure 2 below presents the waveform and spectrogram of the compound mui sɛ ‘car roof’. It is seen that the target duration of /s/ is the shaded part on the waveform and the high frequency section between the pitch lines on the spectrogram. Figure 2. The waveform and spectrogram of the compound mui sɛ ‘car roof’ The t-test for independent samples is used to investigate the difference of segment durations in each set of compounds. The p-values are expected to be smaller than 5% in order that the mean scores of the two investigated values achieve a significant difference. CHAPTER 4: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4.1 Results Figure 3 below presents the findings regarding the duration of /s/ in each word domain of 2-, 3- and 4-word compounds measured for all of the ten speakers. Coordinate compounds are abbreviated as ‘CC’; and subordinate compounds ‘SC’. Figure 3. Mean /s/ duration for all speakers Paired-samples t-tests were run to investigate statistically significant contrasts in each pair of word constituents in the compounds for all speakers and for each speaker. The null hypothesis that there is no significant difference in the mean durations of /s/ in each pair of domains is rejected with p < .05. The results of the t-tests appear to support the null hypothesis thanks to the findings that the speakers make very few significant distinctions among the domains of the compounds. Besides, it is observed from the chart that there are uniformly very small differences in either of the two directions that segments in larger words are longer or shorter than those in smaller words. Therefore, despite the statistical significance, these differences seem to have no linguistically meaningful value in the whole picture of the effect of recursive prosodic words on 22 segmental duration investigated in the study. Instead, they are likely to behave in a random manner, which may be due to the variation in the speakers’ speech production. Generally speaking, there is no significant difference among the word domains of the investigated compounds; that is, prosodic word recursion does not cause any domain-initial strengthening. 4.2 Discussion This paper addresses the issue of domain-initial strengthening in recursive prosodic words; specifically it investigates the question whether prosodic word recursion causes articulatory strengthening to segments at the left edges of recursively embedded word constituents. The results show that there are few statistically significant distinctions among the word domains of 2-, 3- and 4-word compounds investigated in the current study. These distinctions are relatively small, which is consistent across the compounds for all speakers and for each speaker. Therefore, their effects as well as their direction of difference are not likely to play any crucial role in deciding whether prosodic word recursion causes articulatory variation. On the other hand, the much larger and more uniform part of the findings show that the speakers participating in the study do not distinguish the word constituents of the tested compounds, which strongly supports the conclusion that there is no effect of prosodic word recursion on segmental articulation. Domain-initial strengthening concerns the articulatory strength of phonetic segments at the left boundaries of prosodic constituents; those in higher prosodic domains are expected to be temporally and/or spatially stronger than those in lower prosodic domains. The prosodic structure of languages is currently employed as the scale of prosodic positions in the studies of domain-initial 23 strengthening. In such the scale, the prosodic constituents of different categories are hierarchically embedded in the way that the higher ones contain the lower ones; that is, the labeling of prosodic domains is subject to the depth of their embedding. Thus the phenomenon of domain-initial strengthening found in the studies with the use of this scale reflects the effect of the depth of the structural embedding; segments in higher-embedded levels are found to have more linguopalatal contact and/or longer duration than those in lower embedded levels (Fougeron & Keating 1996; Hsu & Jun 1998; Hayashi et al. 1999; Keating et al. 1999; Cho & Keating 2001; Fougeron 2001; and others). At the same time, domain-initial strengthening informs the categories of the prosodic domains. The more strongly articulated segments mark the higher prosodic boundaries in the prosodic structure. The strengthening details provide prosodic cues for listeners to recognize the prosodic hierarchy of languages (Keating et al. 1999; Cho & Keating 2001; Cho et al, 2007). In the current study, the employment of a different scale of prosodic positions, i.e., recursive prosodic words challenges the role of the embedding and labeling of prosodic domains in the issue of domain-initial strengthening. The question is which of them does matter in the strengthening of speech segments. The first hypothesis is that the depth of prosodic embedding causes articulatory variation; that is, segments at the left edges of larger constituents are stronger than those at the left edges of smaller constituents. The second hypothesis is that no strengthening effect is found; there is no significant articulatory variation of segments in the initial positions of recursive prosodic words. The findings of the study support the second hypothesis. There is no significant difference among the word domains of 2-, 3- and 4-word compounds. Therefore, it may be concluded that prosodic word recursion does not cause any articulatory strengthening to 24 segments at the left edges of recursively constructed words; therefore, the phenomenon of domain-initial strengthening is sensitive to the type or category of prosodic constituents rather than the depth of prosodic embedding. CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION The paper addresses the issue of domain-initial strengthening in recursive prosodic words. Domain-initial strengthening concerns the effect of prosody on articulation of segments at the left edges of prosodic domains. It has been investigated in different studies with the use of the prosodic hierarchy as the scale of prosodic positions. The prosodic hierarchy is a hierarchically organized structure of prosodic constituents; the higher ones dominate and contain lower ones. Therefore, the pattern of domain-initial strengthening is that segments in higher prosodic levels are more strongly articulated than those in lower levels. The current study employs a different scale, that is, recursive prosodic words in which larger word constituents contain smaller word constituents. The duration of the voiceless fricative /s/ is measured when it is in the initial positions of each word of 2-, 3- and 4-word Vietnamese noun compounds in order to investigate the effect of prosodic recursion on segmental articulation. The findings show that the speakers make few distinctions among the word domains of the tested compounds. This reflects that prosodic recursion has no strengthening effect on the articulation of speech segments. Furthermore, it shows that the types or categories of prosodic constituents matter in the phenomenon of domain-initial strengthening. The speakers somehow acknowledge that recursively embedded domains belong to the same categories. The paper is the very first study concerning the issue of domain-initial strengthening in recursively embedded structures. It explores a new angle in a well-researched issue of domain-initial strengthening. Therefore, it is expected to attract more research on the effect of prosodic recursion and segmental 26 strengthening which can be extended to different languages, different recursive word patterns and different recursive domains. REFERENCES REFERENCES Al Taisan, Huda. 2011. Domain-initial articulatory strengthening: Seal duration in Arabic. Fresno, CA: MA papers at California State University, Fresno. Baroni, Mitchell. 2011. Domain-initial articulatory strengthening revisited: the case of second language acquisition. Fresno, CA: MA papers at California State University, Fresno. Boersma, Paul. 2001. Praat, a system for doing phonetics by computer. Glot International 5:9/10, 341–345. Cho, Taehong, and Patricia Keating. 2001. Articulatory and acoustic studies of domain-initial strengthening in Korean. Journal of Phonetics 29. 155–190. Cho, Taehong. 2005. Prosodic strengthening and featural enhancement: evidence from acoustic and articulatory realizations of /ɑ, i/ in English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 117(6). 3867–3878. Cho, Taehong, and James M. McQueen. 2005. Prosodic influences on consonant production in Dutch: Effects of prosodic boundaries, plural accent and lexical stress. Journal of Phonetics 33 (2005). 121 – 157. Cho, Taehong; James M. McQueen; and Ethan A. Cox. 2007. Prosodically driven phonetic detail in speech processing: The case of domain-initial strengthening in English. Journal of Phonetics 35(2). 210–243. Diep, Quang Ban. 2012. Ngữ pháp tiếng Việt: Theo định hướng ngữ pháp chức năng. Vietnam: Pedagogy University Publisher. Féry, Caroline. 2010. Recursion in prosodic structure. Phonological Studies 13. Fougeron, Cécile, and Patricia Keating. 1996. Articulatory strengthening in prosodic domain-initial position. UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 92. 61–87. Fougeron, Cécile, and Patricia Keating. 1996. Articulatory strengthening in prosodic domain-initial position. UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 92. 61–87. Fougeron, Cécile. 1999. Prosodically conditioned articulatory variations: A review. UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 97. 1–73. 29 Fougeron, Cécile. 2001. Articulatory properties of initial segments in several prosodic constituents in French. Journal of Phonetics 29. 109–135. Green, Antony D. 2008. Coronals and compounding in Irish. Linguistics: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Language Sciences 46(2). 193–213. Grijenhout, Janet, and Bariș Kabak. (ed.) 2009. Phonological domains: Universals and deviations. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Hayashi, Wendy; Chai-Shune Hsu; and Patricia Keating. 1999. Domain-initial strengthening in Taiwanese: A follow up study. UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 97. 152–156. Hsu, Chai-Shune K., and Sun-Ah Jun. 1998. Prosodic strengthening in Taiwanese: Syntagmatic or paradigmatic? UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 96. 69– 89. Ingram, John, and Thu Nguyen. 2006. Stress, tone and word prosody in Vietnamese compounds. Proceedings of the 11th Australian International Conference on Speech Science & Technology, ed. Paul Warren & Catherine I. Watson. ISBN 0958194629. University of Auckland, New Zealand, December 6 – 8, 2006. Inkelas, Sharon. 1990. Prosodic constituency in the lexicon. The USA: Garland Publishing, Inc. Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2008. The extended prosodic word. In Grijenhout & Kabak, 135–194. Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2009. Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. Prosody Matters: Essays in Honor of Elisabeth Selkirk, ed. by T. Borowsky, S. Kawahara, T. Shinya and M. Sugahara. London: Equinox Publishers. Kabak, Bariș, and Anthi Revithiadou. 2009. An interface approach to prosodic word recursion. In Grijenhout & Kabak, 105–134. Keating, Patricia; Taehong Chong; Cécile Fougeron; and Chai–Shune Hsu. 1999. Domain-initial articulatory strengthening in four languages. UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 97. 139–151. Kirby, James P. 2011. Vietnamese. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 41/3. 381–392. 30 Kuzla, Claudia; Taehong Cho; and Mirjam Ernestus. 2007. Prosodic strengthening of German fricatives in duration and assimilatory devoicing. Journal of Phonetics 35. 301–320. Kuzla, Claudia, and Mirjam Ernestus. 2011. Prosodic conditioning of phonetic detail in German plosives. Journal of Phonetics 39 (2011). 143 – 155. Ladefoged, Peter, and Keith Johnson. 2011. A course in Phonetics (6th ed.). The USA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. Ngo, Thanh Nhan. 1984. The syllabeme and patterns of word formation in Vietnamese. New York: NYU Doctoral dissertation. Nguyen, Dinh Hoa. 1997. Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt không son phấn. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. Nguyen, Thi Anh Thu. 2010. Rhythmic pattern and corrective focus in Vietnamese polysyllabic words. Mon – Khmer Studies 39. 1–28. Nguyen, Thien Giap. 2011. Vấn đề “Từ” trong tiếng Việt. Vietnam: National University Publisher. Nguyen, Van Khon. Usual Vietnamese English dictionary. Taiwan: Khai Tri Bookstore. Schiering, René; Balthasar Bickel; and Kristine A Hilderbrandt. 2010. The prosodic word is not universal, but emergent. Journal of Linguistics 46(3). 657–709. Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1995. The prosodic structure of function words. Optimality Theory, ed. by J. Beckman, S. Urbanczyk and L. Walsh. University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers, GLSA, Amherst. Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2009. The syntax-phonology interface. The Handbook of Phonological Theory, ed. by John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle and Alan Yu. Oxford: Blackwell. Tabain, Marija, and Pascal Perrier. 2005. Articulation and acoustics of /i/ in preboundary position in French. Journal of Phonetics 33 (2005). 77 – 100. Tabain, Marija, and Pascal Perrier. 2007. An articulatory and acoustic study of /u/ in preboundary position in French: The interaction of compensatory articulation, neutralization avoidance and featural enhancement. Journal of Phonetics 35 (2007). 135 – 161. 31 Thompson, Laurence E. 1987. A Vietnamese reference grammar. Honolulu: University of Washington Press. Vigário, Marina. 2010. Prosodic structure between the prosodic word and the phonological phrase: Recursive nodes or an independent domain? Linguistic Review 27(4). 485–530. APPENDICES APPENDIX A: VIETNAMESE NOUN COMPOUNDS (1) 2-word coordinate compounds a. sác vɤ̉ book notebook ‘books’ b. bàn ɣé table chair ‘furniture’ c. bát jĩə bowl plate ‘dishes/ dinnerware’ d. cùə cièn pagoda temple ‘temples/ pagodas’ e. kɔn cáu child grandchild ‘offspring/ descendants’ f. Ɂéc ɲái frog tree toad ‘batrachians’ g. zʌ́i bút paper pen ‘desk supplies’ h. mɯə zɔ́ rain wind ‘inclement weather’ 35 i. fó fɯɤ̀ŋ street guild ‘streets’ j. thɔ́k lúə paddy rice ‘rice’ k. kʌi kɔ̉ tree grass ‘vegetation’ l. thwièn bɛ̀ boat raft ‘boats’ m. soŋ núi river mountain ‘country’ n. ɲɑ̀ kɯ̉ə house door ‘houses’ o. ʈʌu bɔ̀ buffalo ox/cow ‘livestock’ (2) 4-word coordinate compounds a. lɔŋ lʌn dragon unicorn kwi fụŋ turtle phoenix 36 ‘set of four symbolic animals’ b. doŋ tʌi nam bǽk east west south north ‘directions’ c. kɤm Ɂɑ́u ɣɑ͎u tièn rice blouse rice money ‘daily earnings’ d. ŋeu sɔ̀ Ɂók hén shell oyster snail mussel ‘a drama title’ e. hỉ nọ Ɂái Ɂó happiness anger love disgrace sáŋ ʈɯə cièw tói morning afternoon evening night ‘emotions’ f. ‘different times of a day’ g. koŋ juŋ ŋon hạɲ labor beauty speech behavior ‘four female virtues’ h. dʌ́t dai earth land ruọŋ vɯɤ̀n field garden ‘lands and farms’ i. ʈɤ̀i ʈæŋ sky moon cloud wind ‘weather’ mʌi zɔ́ 37 j. nɔn soŋ dʌ́t nɯɤ́k mountain river earth water ‘country’ k. soŋ núi bɤ̀ kɔĩ river mountain river bank region núi soŋ ‘country’ l. bɤ̀ kɔĩ river bank region mountain river ‘country’ m. Ɂoŋ bɑ̀ cɑ mɛ͎ grandfather grandmother father mother ‘grandparents and parents’ n. ko jì cú bák aunt aunt uncle uncle ‘aunts and uncles’ o. vɤ͎ còŋ kɔn wife husband kái child child ‘parents and children’ (3) 2-word subordinate compounds a. sɛ bɔ̀ vehicle cow/ox ‘cow/ox cart’ b. fɔ̀ŋ xác room guest ‘living room’ 38 c. sɛ ŋɯ͎ə vehicle horse ‘horse cart d. cʌn zɯɤ̀ŋ leg bed ‘bed leg’ e. súŋ mái gun machine ‘machine gun’ f. bɔ́ŋ dɑ́ ball to kick ‘football’ g. ŋɯɤ̀i Ɂɤ̉ person to reside ‘servant’ h. ŋɯɤ̀i làm person to do ‘servant’ i. bàn ủi table to iron ‘iron’ j. bɔ́ŋ cwièn ball to pass ‘volley ball’ k. kɑ̀ cuə 39 eggplant sour ‘tomato’ l. dɯɤ̀ng kɑ́i road main ‘main road’ m. dũə kɑ̉ chopstick big ‘stirring chopstick’ n. tiéŋ fáp language French ‘French’ o. báɲ ŋɔ͎t cake sweet ‘cake’ (4) 3-word subordinate compounds with left-edged heads a. búə thɤ͎ rèn hammer worker smith ‘sledgehammer’ b. kwán kɤm ɣɑ̀ store rice chicken ‘chicken rice store’ c. Ɂien sɛ ŋɯ͎ə saddle vehicle horse ‘horse cart saddle’ d. bọt xwai mì 40 flour potato wheat ‘cassava flour’ e. kʌi kɑ̀ cuə tree eggplant sour ‘tomato tree’ f. dạn súŋ mái bullet gun machine ‘machine gun bullet’ g. bɤm sɛ dạp pump vehicle bike ‘bike pump’ h. thʌn kʌi kaw body tree areca ‘areca tree body’ i. nǽp cai sɯ̃ə lid bottle milk ‘milk bottle lid’ j. kɑ́ nɯɤ́k ŋɔ͎t fish water sweet ‘fresh water fish’ k. vɔ̉ ʈɯ́ŋ vịt shell egg duck ‘duck eggshell’ l. ɲãn cai rɯɤ͎u label bottle wine 41 ‘wine bottle label’ m. cuoŋ ɲɑ̀ bell thɤ̀ house worship ‘church bell’ n. xuŋ kɯ̉ə sỏ frame door book ‘window frame’ o. kàŋ kuə claw crab dòŋ field ‘fresh water crab claw’ p. sɛ bɑ báɲ vehicle three wheel ‘three-wheel cart’ (5) 4-word subordinate compounds with left-edged heads a. ʈɯɤ̉ŋ dọi bɔ́ŋ captain team ball dɑ́ kick ‘football team captain’ b. nǽm kɯ̉ə fɔ̀ŋ xác wisp door room guest ‘living room door knob’ c. củ kwán kɤm owner store rice ɣɑ̀ chicken ‘chicken rice store owner’ d. màu vɔ̉ sɛ color tire vehicle dạp bike 42 ‘bike tire color’ e. tiéŋ cuoŋ ɲɑ̀ sound bell thɤ̀ house worship ‘church bell sound’ f. kɤ̃ nǽp cai sɯ̃ə size lid bottle milk ‘milk bottle lid size’ g. ʈɯɤ̉ŋ dọi bɔ́ŋ captain team ball cwièn pass ‘volleyball team captain’ h. màu Ɂien sɛ ŋɯ͎ə color saddle vehicle horse ‘horse cart saddle color’ i. vièn xuŋ kɯ̉ə sỏ border frame door book ‘window frame border’ j. vɔ̉ dạn súŋ case bullet gun mái machine ‘machine gun bullet case’ k. vʌi kɑ́ nɯɤ́k ŋɔ͎t fin fish water sweet ‘fresh water fish fin’ l. màu ɲãn cai rɯɤ͎u color label bottle wine ‘wine bottle label color’ 43 m. nǽp họp kɤm nǽm lid box rice wisp ‘rice ball box lid’ n. vʌi duoi kɑ́ biẻn fin tail fish sea ‘sea fish tail fin’ o. duoi kɑ́ nɯɤ́k ŋɔ͎t tail water sweet fish ‘fresh water fish tail’ (6) 4-word subordinate compounds of two 2-word subordinate compounds a. bɯ́k tɯɤ̀ŋ tìɲ piece wall Ɂieu sentiment love tìɲ Ɂieu sentiment love ŋɯɤ̀i cɤi bɔ́ŋ cwièn person play ball pass ‘love wall’ b. bài hát piece sing ‘love song’ c. ‘volley ball player’ d. áɲ sáŋ dɛ̀n reflection bright light electricity ‘electric light’ e. bản dò ɲɑ̀ mɑ́i piece draw house machine ‘factory map’ die͎n 44 f. sɯ͎ tíc thing legend kɑ́ vɔi fish elephant ‘whale legend’ g. sɛ hɤi dò cɤi vehicle car thing play mɑ́i tíɲ sác machine calculator carry hand sɛ lɤ̉ə hɤi nɯɤ́k vehicle fire gas water mɑ́i bɑi sieu thaɲ machine fly super sound ‘toy car’ h. tɑi ‘laptop’ i. ‘steam train’ j. ‘supersonic plane’ k. ŋɯɤ̀i sɛm ʈwièn hìɲ person watch transmit image ‘television audience’ l. sɛ dạp dò cɤi vehicle bike thing play tiéŋ aɲ ‘toy bike’ m. dè thi text exam language English ‘English test’ n. sɯ͎ tíc jɯə hʌ́u 45 thing legend melon name of a melon ‘watermelon legend’ o. bản mʌ̃u piece sample ‘test sample’ dè thi text exam