identifiable dimensions to effective global supply chains: the role of

advertisement

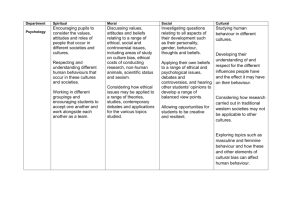

IDENTIFIABLE DIMENSIONS TO EFFECTIVE GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAINS: THE ROLE OF CULTURE SUSAN A HORNIBROOK & PAMELA M YEOW Kent Business School University of Kent Parkwood Road Canterbury, Kent CT2 7PE United Kingdom Telephone: (44) (0)1227 827731, (44) (0)1227 823991 Fax: (44) (0)1227 761187 Email: s.a.hornibrook@kent.ac.uk p.m.yeow@kent.ac.uk WORK IN PROGRESS (3) Paper prepared for the 28th International Congress of Psychology (ICP2004) in Beijing, China, 8-13 August 2004. 1 2 ABSTRACT 3 1. Introduction The continuing globalisation of food manufacturing, together with the more recent moves towards internationalisation of major food retailers such as Tesco, Metro, Carrefour and Wal-Mart, poses a number of significant challenges to all firms along the supply chain. In Europe, and particularly the UK, own brand products are a key component of competitive strategy, and in order to guarantee food quality and safety, retailer-led domestic vertically co-ordinated supply chains have emerged (Hornibrook and Fearne 2001). As European retailers seek growth through international expansion in order to combat market saturation and low growth in domestic markets, the strategic importance of own brand products and economies of scale associated with global sourcing will become increasingly significant. In addition to food quality and safety, a number of other critical supply chain issues including ethical and environmental concerns are also driving closer relationships between food retailers and their first and second tier suppliers. Given the increasing globalisation of both trade and markets for food, and the need for closer relationships and management of the supply chain, the impact of culture on relationships between firms in geographically and culturally diverse supply chains becomes particularly significant. Researchers from various academic disciplines have adopted a number of different economic and management theoretical perspectives in order to examine supply chain management, in particular transaction cost economics, systems theory, game theory and channel management. This paper seeks to build on previous work that considers vertically co-ordinated supply chains as strategic responses to perceived risk (Hornibrook and Fearne, 2001, 2003) by examining the role of culture (Hofstede, 1980, 1994; Schein, 1985, 1990; Trompennars., 1993; Yeow, 2000, 2002; Erez and Gati, 2004). By adopting a cross-disciplinary behavioural perspective and including a psychological dimension, the authors seek to add to the supply chain management and organisational behaviour literature by developing a framework for the examination of cross cultural supply chain relationships. Given the emerging significance of China as a potential market and source of supply for western food firms, and the different perspectives on personal and business relationships between Asia and the West (Liu and Wang, 1999), the paper develops a number of propositions within the framework 4 to identify and discuss the impact of culture on perceptions of risk, using the example of Tesco’s recent expansion into China as a case study. Additionally, the paper will identify areas suitable for further research regarding the consequences of culture and perceived risk on global supply chains. This paper contributes to the supply chain literature in two ways. It adopts an interdisciplinary approach to supply chain management and presents a theoretical framework for the examination of the role of culture on effective supply chain management. The paper is presented in four parts. The first section sets the scene by discussing the globalisation of the food industry, supply chain management and implications for firms. The second section critically discusses the application of Perceived Risk Theory to supply chains, in particular the failure of the framework to account for the effect of culture on behaviour. Other theoretical perspectives that do take account of cultural differences are introduced in the third section, and the proposed theoretical framework is introduced in the fourth section. Next, the framework is tested using the example of the UK food retailer, Tesco, and their recent expansion into China. The final part draws some conclusions and presents recommendations for further research. 2. Supply Chain Management 2.1 Globalisation and the Food Industry Paton and McCalman (2000:7-8) identified a number of major external changes that all organisations are currently addressing or will have to come to terms with in the 21st Century. These include the development of enhanced technologies and increased competition due to world-wide historical, political and economic changes; worldwide recognition of the increasing importance of finite resources and the environment as an influential variable; health consciousness as a permanent trend across all age groups and a growing awareness and concern associated with food production and consumption throughout the developed world; changes in lifestyle trends affecting the way people view work, purchases, leisure time and society; changes in the workplace creating a need for non-traditional employees; and the crucial role of knowledge and people to the competitive well being of organisations. 5 In addition to the above general changes, the food industry has been subject to a number of specific environmental changes that have affected and driven international and global activity. Drivers of the increase of cross border trade in agricultural and food products include the reduction of national tariffs and non-tariff barriers (WTO, 2003), standardisation of food safety and quality standards (WHO, 2003), consumer demand, and firm strategic behaviour (Fearne et al, 2001). As a result, the food industry has become interdependent and global, instead of simply international (Varzakas and Jukes, 1997). Globalisation is not just limited to the range of a firm’s activities across geographical markets, but also the extent of contractual co-operation with other firms (Mattsson, 2003). As a consequence, actions, events and decisions taken in one part of the world will have a significant impact on individuals and communities in other, more distant, parts of the earth (McGrew, 1992). Globalisation therefore, has implications for those firms such as multinational food manufacturers and more recently European retailers, whose commercial reputation and success depends upon branded products sourced and produced by suppliers who may operate under different environmental conditions. The drive for more consistent eating quality has become a competitive strategy amongst UK food retailers to gain market share through improved margins and customer loyalty (IGD 2003), and has led to various attempts at marketing differentiated retail branded products sourced through retailer-led co-ordinated supply chains. Own brands, as defined by Davis (1992) are positioned as niche, high quality products sold at a premium price, supported by strong technical and quality control involvement from the retailer. UK retailers do not produce own brand products but delegate the task of production to a small number of large suppliers, with whom they develop close relationships. Such businesses that participate in co-ordinated relationships remain distinct in the legal sense, but in other respects, extend their influence beyond their organisational boundaries. The structure of the UK retailing sector is such that market power is a feature, with multiple retailers able to impose their requirements very effectively on the supply chain (Northern, 2000). However, the economic benefits resulting from the success of own brands are offset by an increase in the level of risk for those retailers who invest in own brand products. The more detailed their requirements and instructions to their upstream suppliers, the more 6 they are held responsible for the safety and quality of the end product by both regulators and consumers. By delegating the task to upstream suppliers, the need for control, communication and information is paramount in order to protect the retailers’ reputation and market share. Supply chain management is therefore seen as crucial by UK retailers, particularly in relation to maintaining food quality and safety. In the UK, consumers have become increasingly concerned about food safety and quality issues, particularly those risks that have potentially severe consequences, and are little understood, such as nvCJD. However, other emerging and high profile issues that may impact upon brand image and reputation are beginning to attract interest by supply chain researchers and practitioners. These areas include environmental issues such as pollution, resource depletion and waste management, as well as ethical issues (New, 2004b) relating to labour and human rights, employment practices, bribery and corruption, and corporate governance. In today’s challenging global markets, the management of relationships are viewed as a key element of successful supply chains (Christopher, 2004). 2.2 Theoretical Roots and Approaches The concept of Supply Chain Management (SCM) has developed over time from having an intra-organisational focus on logistics to becoming focused on wider interorganisational issues. Although practitioners and academics use the term widely, there is no universally agreed definition (Dubois et al, 2004). The main tensions arise between those who adopt a functional perspective and view SCM as an overall term for logistics - managing the flow of materials and products from source to user - with the focus on operational issues. Others view SCM as a management philosophy concerned with the management of supply and demand across traditional boundaries – functional, organisational and relational – and recognises that by doing so, organisations will gain commercial benefits (New, 1996). This research recognises the latter approach, in which the scope of SCM is defined as wider than that of logistics, is driven by the need to develop competitive advantage for all firms in the supply chain, and involves collaboration across functional, organisational and individual boundaries. The emphasis is on key supply chain-wide business processes across the whole supply chain, including customers and consumers (customer relationship management, demand management, order fulfilment, manufacturing flow 7 management, supplier relationship management, product development and commercialisation) rather than individual business functions (Figure 1). Figure 1: Simplified Food Supply Chain Consumers Key: Retailers Processors Farmers Information flow Product flow Given the above, this research adopts the Global Supply Chain Forum’s definition of SCM (1998), which is ‘Supply chain management is the integration of key business processes from end user through original suppliers that provides products, services, and information that add value for customers and other stakeholders”. Supply Chain Management therefore views the supply chain as an extended enterprise or organisation, utilising all available skills and resources in order to enable each individual firm as well as the system as a whole to achieve competitive advantage (Bailey et al, 2004). The most significant management challenge is to promote, facilitate and encourage a willingness to collaborate, both between functions within the firm, and across firms in the supply chain, which may involve national and geographic borders. The development of global supply chains are viewed as a mechanism by which firms can achieve a competitive advantage by utilising the unique comparative advantages offered by the diverse nations that make up the chain (Prasad and Sounderpandian, 2003). Researchers from various academic disciplines have adopted a number of different economic and management theoretical perspectives in order to examine supply chain management, including but not limited to operational research, contingency theories, industrial dynamics, social networks theories, transaction cost analysis, agency theory, game theory, value chain, resource based theory, lean supply, virtual organisations, and supply chain integration (for a full discussion, see Giannakis et al, 2004). 8 Critics of the operational perspective adopted by economists, sociologists and organisational theorists have noted the need to adopt a multidisciplinary approach (Nassimbeni, 2004; Harland et al, 2004) and have called for different ways to conceptualise the problems faced by manufacturers, retailers and distributors (New, 2004). In the UK, a series of high profile food safety and quality incidents, changes in both public and private regulation of the market, and the greater exposure to the risks of product failure for retail brands have increased risk for all stakeholders. Supply chains operating across geographic and national borders will encounter increased cultural and ethnic diversity in comparison to domestically based supply chains, which in turn will affect the risks associated with food safety and quality, and consequent consumer and organisational behaviour. From a theoretical perspective, the risk perceptions of both consumers and organisations (Zwart and Mollenkopf, 2000, Yeung and Morris 2001) and the impact of culture on such perceptions cannot be ignored when examining global supply chain behaviour. 3. Perceived Risk Theory Different interpretations and approaches to risk can be identified in the literature. Scientists and policy makers in western societies view risk objectively, assuming that the probabilities and consequences of adverse events can be identified and quantified. This notion is rejected by many social scientists, who argue instead that such a view is incomplete at best and misleading at worst, and that risk “does not exist “out there”, independent of our minds and cultures, waiting to be measured” (Slovic, 2002:4). The focus of the approach in the sociology and psychology literature is therefore on the effects of perceptions of risk on individual behaviour. Initial research into consumer behaviour began in the 1960’s, informed by theory borrowed from social and clinical psychology, anthropology and sociology (Cox, 1967). Perceived Risk Theory (Cox, 1967; Bauer, 1967; Dowling and Staelin, 1994) asserts that consumers perceive risk in a buying situation because the resultant consequences cannot be known in advance, and that some such consequences are likely to be unpleasant. Researchers note that risk perception is shaped more by the severity of the consequences than the probability of occurrence (Slovic, Fischoff, Lichenstein, 1980; Diamond, 1988; Mitchell, 1998). The theory also notes that the consequences from a purchase can be divided into various types of loss: performance, 9 psychosocial, physical, financial and time (Mitchell, 1998). Performance risk can be viewed in two ways: either as a surrogate measure for overall risk in that the product results in a combination of other losses (Mitchell, 1998) or does not perform as expected (Sweeney, Soutar, Johnson, 1999; Schiffman and Kanuk, 1994). Financial risk is defined as a net financial loss, physical risk relates to the possible danger or harm to the individual or to others, time risk is associated with the loss of time and effort associated with achieving satisfaction with a purchase. Psychosocial risk relates to possible loss of self-image or self-concept as a result of a purchase or use (Murray and Schlacter, 1990) or social embarrassment (Schiffman and Kanuk, 1994). The overall level of perceived risk is viewed as the sum of the attributes’ perceived risk levels, with the degree of risk perceived varying by individual consumer, depending on risk tolerance and wealth level, both of which impact upon the ability to absorb a loss. If perceived risk exceeds the tolerable degree of the individual level, then this triggers the motivation for risk-reducing behaviour. Such perceptions of risk can be reduced through various risk reducing strategies, including increasing information and reducing the consequences. Theoretical debate on the possible impact of organisation’s perceptions of risk on complete supply chains has only recently emerged (Christopher, 2004; New, 2004; Lamming, Caldwell and Phillips, 2004, Hornibrook, 2002). In addition to consumers, the impact of perceived risk on a purchase decision could also be extended to business-to-business sourcing situations (Mitchell, 1998). Peters and Venkatesan (1973) confirm that organisational buyers are affected by many of the same variables that affect consumers, including perceived risk, an observation also supported by March and Shapira (1987), Mitchell (1998) and Greatorex, Mitchell and Cunliffe (1992). Generally, empirical research has focused on the perceived risk and risk handling strategies of industrial buyers associated with choosing a supplier (Puto, Patton and King, 1985; Hawes and Barnhouse, 1987; Greatorex, Mitchell and Cunliffe, 1992). Most recently, Perceived Risk Theory has been utilised, using a supply chain methodology, to examine vertically co-ordinated supply chains comprising consumers, retailers, processors and farmers in the UK food industry. Supply chain management is therefore viewed as a strategy to manage perceived risk, for both consumers and organisations at different stages in the supply chain (Hornibrook and Fearne, 2001, 2003). 10 The above describes a number of theoretical approaches, in particular Perceived Risk Theory, to describe and explain supply chain behaviour. However, a number of criticisms and limitations can be noted regarding current theory in general, and Perceived Risk Theory in particular. Perceived Risk theory makes some attempt to acknowledge the context and history of actions and behaviour. However, although culture is identified as one determinant of risk perception (Joffe, 2003, Slovic, 2002), the theory does not include the role of culture in determining risk perception and the subsequent influence on risk reducing behaviour. Additionally, the theory adopts individual dimensions of loss (physical, time, financial, psychosocial, performance) that may only be appropriate in western societies and may be limited in its scope for understanding global supply chains that span different countries and cultures. Previous empirical research has been limited to small, domestically orientated supply chains in the UK. One of the main criticisms of both normative and descriptive research into supply chains is that the prevailing SCM literature tends to use theoretical assumptions that simplify the complex reality of interconnecting relationships between a host of different actors (Dubois et al, 2004). Most research occurs at the dyad, limited attempts have been made to examine relationships along product supply chains (Hornibrook, 2002), and more recently, interest has extended to links among supply chains (Dubois et al 2004). However, the dominant paradigm has been the Newtonian style in which an idealised world is constructed in the form of an abstract model, in order to approximate the behaviour of real objects (Tsoukas, 1998); to examine and then to predict future behaviour without taking account of context and history. The focus is on linear relationships, the organisation as a machine, agents as objects, generalisability, observation, and universal laws. Given that supply chains are extremely complex (Cox, 1999; Christopher, 2004; Dubois et al, 2004), the use of oversimplified linear models and a Newtonian perspective would seem to be inappropriate. Globalisation of firms and markets involves reorganisation and confrontation between cultures, both at the organisational and the national level (Mattsson, 2003). The need to understand the role of culture on 11 the effective management of different supply chain issues is highlighted by a number of observers (Mattsson, 2003; Robertson and Crittenden, 2003; Prasad and Sounderpandian, 2003; Weaver, 2001; Schneider & Barsoux, 2003). 4. Culture and Globalisation Globalisation can be defined as the process by which cultures influence one another and become more alike through trade, immigration and the exchange of information and ideas. As such, the reach of globalisation extends to every part of the world, but cultures differ greatly in how much they have been affected by it with considerable variations within regions and within countries (Arnett, 2002). Culture comprises divergent behaviours, norms and expectations and is fluid across space and time (Ettlinger, 2003) and can be viewed as the patterns of cognitions and behaviour shared by a group which evolve and becomes manifest in continuous processes of social interaction. As beliefs and attitudes are important determinants of perceived risk, interdisciplinary research is required to investigate the role of culture in determining perceived risk, and the consequent influence of culture on organisational behaviour and global supply chains. Much work has been done in the importance in considering notions of culture in terms of global organisations, virtual or otherwise (e.g. Schein, 1989, 1990; Hofstede, 1980, 1994; Hampden-Turner & Trompennars, 1993; Trompenaars, 1993), particularly addressing the classification of cultural patterns. Alongside such work, a continuing debate has been conducted regarding a) the appropriate level of analysis, as culture level analysis reflects central tendencies for a country but does not predict individual behaviour, and b) that differences in cultural patterns should be identified through behaviour or values (Dahl, 2004). Hofstede carried out large cross-cultural studies and identified five dimensions of differences or traits between national cultures. These were labelled power-distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity and long-term/short-term orientation. Power-distance indicates the extent to which a society accepts that power is distributed unequally, with high power distance cultures accepting inequality and respect for social status and class; low power distance societies are more likely to value equality. Uncertainty avoidance indicates the extent 12 to which people in a society feel threatened by ambiguous or unpredictable circumstances. Individualism/collectivism represents the degree that cultures vary in their emphasis on individualistic or collectivistic views of social life and personal identity, and the degree to which they value group ties, which may be loose or strong. Societies also range in characteristics that are associated with masculinity and femininity, with members of masculine cultures viewing the world in terms of winners and losers and feminine cultures discouraging the notion of competition. The final dimension is the extent to which societies have different time horizons, either long term or short term, and whether they value the past or are more future orientated. Other researchers have added to these cultural dimensions (Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, 1961….etc) Although there been accolades to his work, there have also been many criticisms. One major problem with Hofstede’s approach is methodological. Cray and Mallory (1998) write that the use of aggregated national data can be misleading when applying societal characteristics to individual behaviour because there can be considerable variance in the degree to which individuals adhere to any set of values. Others (cf. Dorfman & Howell, 1988; Goodstein, 1981; Hunt, 1981; Robinson, 1983; Sondergaard, 1994) have also criticised his scales in terms of their validity and usefulness of their four dimensions at the individual level of analysis. It was argued that it is not possible to discuss the impact of cultures on organisational structures if all the data originates from the same study (Tayeb, 1988), with Hunt (1981:62) questioning whether Hofstede was “studying the culture of the Japanese or the French or the British or Malaysian executive or the culture of a multinational firm”. A further criticism is that underlying values are derived from a measurement instrument in which the focus is on the ultimate goal state, therefore the resultant underlying values are frequently the result of very little data (Dahl, 2004). A different approach in developing a framework in which to understand cultural differences has been adopted by Schwartz (1992, 1994), who clearly distinguishes between individual level analysis and culture level analysis in comparison to the work of Hofstede and others (Dahl, 2004). This approach develops parallel sets of concepts applicable to different levels of analysis, ie at the individual level and at the culture level. Using data from more than 60,000 located in 63 countries, Schwartz derived 13 ten motivationally distinct value types that are likely to be recognised within and across cultures, at an individual level of analysis (Table 1.). Table 1: Definitions of Motivational types of Values Power Achievement Hedonism Stimulation Self Direction Universalism Benevolence Tradition Conformity Security Social status and prestige, control or dominance over people and resources (authority, social power, wealth, preserving public image) Personal success through demonstrating competence according to social standards (ambitious, successful, capable, influential) Pleasure or sensuous gratification for oneself (pleasure, enjoying life, self-indulgent) Excitement, novelty and challenge in life (daring, a varied life, an exciting life) Independent thought and action – choosing, creating, exploring (creativity, freedom, independent, choosing own goals, curious) Understanding, appreciation, tolerance, and protection for the welfare of all people and for nature (equality, social justice, wisdom, broadminded, protecting the environment, unity with nature, a world of beauty) Preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact (helpful, honest, forgiving, loyal, responsible) Respect, commitment, and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provide (devout, respect for tradition, humble, moderate) Restraint of actions, inclinations, and impulses likely to upset or harm others and violate social expectations or norms (selfdiscipline, politeness, honouring parents and elders, obedience) Safety, harmony, and stability of society, of relationships, and of self (family security, national security, social order, clean, reciprocation of favours) Source: Schwartz (2004) Taking a circular perspective, such types of values can be ordered into four higher order value types: “openness to change” which combines stimulation, self-direction and a part of hedonism; “self enhancement” consisting of achievement and power and the remainder of hedonism. On the opposite side of the circle, “conservatism” combines security, tradition and conformity, and “self-transcendence” consists of universalism and benevolence. These higher order value types form a motivational continuum, with values situated on one side of the circle being strongly negatively correlated with values on the opposing side of the circle yet positively correlated with values located closely in either direction around the circle. Later work by Schwartz 14 (2004) has confirmed the theoretical existence of basic values, that tradition lies outside of conformity and that values form a motivational continuum. At the culture level, Schwartz also derives seven value types. Conservatism or Embeddedness emphasises the maintenance of the status quo, propriety and restraint in actions or preferences that could disrupt the group or the traditional order. Hierarchy emphasises the legitimacy of an unequal distribution of power, resources and roles. Harmony emphasises fitting harmoniously into the environment, while Mastery emphasises achievement through active self-assertion. Egalitarianism emphasises foregoing of self interest in favour of voluntary commitment to promoting the welfare of others. Intellectual Autonomy emphasises the desirability of individuals independently pursuing their own ideas and intellectual directions, whereas Affective Autonomy emphasises the desirability of individuals pursuing affectively positive experiences (Smith, Peterson and Schwartz, 2002). These value types are also summarised within three dimensions, namely Embeddedness versus Autonomy, Hierarchy versus Egalitarianism, and Mastery versus Harmony. More recently, theoretical approaches (see Figure 2) have proposed a multi-level model of culture incorporating structural and dynamic dimensions, in which different levels and consequently units of analysis (individual, group culture, organisational culture, national culture and global culture) are nested within each other and are interconnected through reciprocal top-down and bottom-up processes. Top down processes transmit the effects of culture from higher to lower levels, whereas bottomup processes allow behaviours at the individual level, once they are shared by all members of a social unit, to emerge at the macro-level (Erez and Gati, 2004). Globalisation is viewed at the macro level of culture within the model, and is based upon individualism, free market economics, democracy, including freedom of choice, individual rights, openness to change and tolerance of differences, reflecting the values of those Western countries that provide the driving energy behind globalisation (Arnett, 2002). Given that nations differ as to the effect of globalisation, national cultures that exhibit similar characteristics to western values are more likely to embrace the global culture. It is likely, therefore, that the effect of the global culture on the nested levels of culture can be facilitated or hindered by the particular characteristics of the national culture. 15 Research has mainly adopted a within-level orientation, with most work focused on differences and similarities at the national level. Little research has examined culture at multiple levels. At the organisational culture level, research has focused on the shared beliefs and values of members of the same organisation; at the team level, shared values by team members reflect a group culture, whereas at the individual level, culture is viewed as the values as they are represented in the self. Cross-level research examines the congruence between two or more levels (Erez and Gati, 2004). Figure 2: The Dynamic of Top-down-bottom-up Processes across Levels of Culture Top Down Individual Bottom up Group Culture Organisational Culture National Culture Global Culture Source: Erez and Gati (2004) 16 Globalisation offers opportunities to organisations that seek growth, and the dominant strategy to date has been the emergence of the multinational (MNC). Employees who work for MNC’s face potential tension between local/national values and the values of the MNC, as they seek to build horizontal relationships both at the local (national) and at the global (MNC) level. The challenge the challenge for MNC’s is to create a global culture, and managerial role perceptions, without offending local cultural values (Berson, Erez and Adler, 2004). The strategic decision to manage upstream vertical linkages through co-ordination rather than ownership implies a greater challenge, as management of global supply chains will encounter tensions both between and within all levels of culture. If vertically co-ordinated supply chains, rather than vertically integrated organisations, are now viewed as the basis for competition, then this raises a number of questions e.g. do vertically co-ordinated but separate organisations try to create and operate within a global culture? What are the tensions, the dynamics and differences in the cultural values along a global supply chain; is supply chain management more likely to occur between nations that have similar cultural values? 5. Proposed Theoretical Framework Perceived Risk theory has been applied to supply chains but there are three notable criticisms of the approach; namely that the theory is informed by western management concepts of risk and fails to incorporate the effect of culture on perceptions of risk; that supply chains are operating in an increasingly turbulent, changing external and internal environments, and that very limited empirical work using the framework has only been undertaken in the UK. The aim of this paper is to provide a theoretical framework and recommendations for future research that addresses such criticisms. As discussed above, researchers have identified a number of dimensions in which cultures and societies may differ. Such dimensions will have an impact on how the different types of loss associated with Perceived Risk Theory are viewed, both at the individual and at the organisational level, and the strategies employed to reduce such perceptions of risk (Figure 2). Some applications are discussed below. 17 Perceived Risk theory is derived from western values; therefore it is likely that those national cultures with similar values will also identify similar risks and adopt similar strategies to reduce perceived risk at both the individual and organisational level. Figure 2: Interaction between Perceived Risk and Cultural Dimensions NATIONAL CULTURE LEVEL DIMENSIONS: Hofstede Schwartz *Power Distance *Embeddedness *Uncertainty Avoidance * Hierarchy *Individualism/Collectivism * Harmony *Masculinity/Femininity * Mastery *Long term/short term *Egalitarianism Orientation * Intellectual Autonomy * Affective Autonomy PERCEIVED RISK: *Financial Loss *Physical Loss *Time Loss *Performance Loss *Psychosocial Loss RISK REDUCING STRATEGIES *Increase information *Reduce consequences In socially collectivist cultures, where group ties are important, family and other group members are more likely to offer help when required, and this is turn will affect the perception of risk associated with different types of loss. In terms of financial loss, collectivism acts as a cushion against possible losses (Weber and Hsee, 1998), and therefore perceived risk associated with financial loss is likely to be lower than in individualistic societies. In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, risk reducing strategies will favour formal procedures and systems such as codes of conduct, quality and safety assurance schemes, reporting systems, and standardisation of practices, and will favour communication through the spoken and written media. However, in low uncertainty avoidance societies, where contextual clues and subtle messages are crucial to the reception and understanding of a message, formal structures and written documents such as codes of conduct will be ineffective (Weaver, 2001). 18 The degree to which physical risk is perceived will also depend upon variations in beliefs about the extent of individual control over events. For example, symptoms of food borne disease may be perceived as a natural occurrence, for example in societies that seek harmony with the environment, or as a side effect of disease that can be transmitted through food and unhygienic practices, according to different national cultures (Motarjemi and Kaferstein, 1997). In high power distance/hierarchy societies, organisational superiors are treated as experts, inaccessible, unreproachable and entitled to organisational power (Weaver, 2001), and superior-subordinate relationships are likely to be different to those in low power distance or mastery societies, where status and class roles are less important. However, supply chain management is concerned with the management of supply and demand across traditional boundaries, including functional, organisational and relational. In low power distance societies, such a concept is likely to be more acceptable than in high power distance societies, where status and power reside in the formal position rather than in the individual. Supply chain management requires innovation, sharing of information and team working both within organisations and across organisational boundaries, and this may be more achievable in societies that accept the concept of intellectual autonomy, in which an individual actively generates and pursues ideas. 6. Illustrative Example: The case of Tesco and expansion into China Tesco has recently announced its expansion into China, where it has just acquired a 50 per cent holding in Hymall, a Chinese mainland subsidiary of the Taiwan-based Ting Hsin International Group. Hymall has 25 hypermarket outlets based in Shanghai and other major cities, and the two companies will have equal representation on the board. Such a move is viewed as an initial short term strategy to enter the Chinese market but the long term strategy is to establish and build the Tesco retail brand (China Daily, 15 March 2004). In the UK, Tesco, along with the other supermarkets, employ strategies to increase information and to reduce the adverse consequences associated with risks include developing closer and more co-operative vertical relationships with individuals and 19 organisations along the supply chain, in addition to gathering information from a variety of sources. The UK food industry is heavily regulated because of the risks and uncertainty associated with food production and consumption, and information from mandatory government inspections and audits are made publicly available. On the other hand, the industry as a whole, as well as individual firms, also implement a number of code of practices and assurance schemes with which suppliers have to comply. Compliance is assessed through personal visits, or using second or third party monitoring agents, depending on the nature of the scheme. Tesco has based its global growth strategy on complexity reduction, relying on expatriate employees to replicate and provide the systems and key processes, as well as employing and training local managers. For Ting Hsin, the strategic partnership with Tesco will bring benefits, including new product development and supply chain management (BBC News, 14 July 2004). The majority of food is sourced locally, and therefore supply chain management systems and processes developed in the UK are likely to be transferred to the Chinese market. Using the framework developed above to examine the various supply chain practices invoked by Tesco to reduce perceived risk, it can be seen that such procedures and processes may be resisted by both Ting Hsin and their suppliers due to differences in cultural dimensions and perceptions of risk. Formal written codes of conduct and assurance schemes, third party audits and inspections, cross functional teams and exchange of information may all be resisted due to the relatively high levels of collectivism, power distance and importance of “expert roles” in Chinese society. Managers seconded to China from the UK will encounter tensions both within and between different layers of culture driven by differences between local Chinese values and those of Tesco. Tesco will be seeking to develop a global culture embracing western values, and this may lead to resistance within Ting Hsin, and between the organisation and its Chinese suppliers. 7. Discussion Proposed framework allows for the impact of culture on perceived risk theory Also meets some of the criticism directed at Hofstede’s research 20 Allows for increased complexity of global supply chains Further global/international research required to 1) identify other types of loss associated with perceived risk theory for individuals and organisations that may be important for cultures other than western ones, eg relational loss, 2) research into effect of culture both within and between different levels (individual, group, organisational, national, global) on supply chain management. 21 References Adler, N. (1991). International Dimensions of Organisational Behaviour, Boston: Kent Publishing Co. Arnett, J. J. (2002). The Psychology of Globalisation, American Psychologist, Vol. 57, No. 10, pp774-783. Bauer, R. A. 1967. Consumer Behaviour as Risk Taking, in Risk Taking and Information Handling in Consumer Behaviour. Harvard University Graduate School of Business Administration, Boston, pp 23-33. Berson, Y., Erez, M., Adler, S. (2004). Reflections of Organisational Identity and National Culture on Managerial Roles in a Multinational Corporation, Best Paper Proceeding, Academy of Management, August. Boisot, M & Child, J. (1999). Organizations as adaptive systems in complex environments: The case of China. Organization Science, 10, 3, 237-252. Bolton, J. & Wei, Y. (2004). Supply chain Management in China: Trends, Risks and Recommendations, Ascet Volume 6, Accenture. Chinese Embassy, 2004. The Development of China’s Agriculture, http://www.chinese-embassy.org.uk/eng/jjmy/t27097.htm, accessed 5 April 2004. Christopher, M. 2004. Supply Chains: A Marketing Perspective, in Supply Chains, Concepts, Critiques and Futures, Eds. S. New and R. Westbrook, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 23-42. Cox, D.F. (1967). Risk Taking and Information Handling in Consumer Behaviour, Harvard University Press, Boston, MA. Cox, T. (1991). The multicultural organization. Academy of Management Executive, 5, 2, 34-47. Cray, D & Mallory, G.R. (1998). Making Sense of Managing Culture. London: International Thompson Business Press. Dahl, S. (2003). An Overview of Intercultural Research, Society for Intercultural Training and Research UK, 1 – 10 (2/2003), London. Davis, G. 1992, The Two Ways in Which Retailers can be Brands, in International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 20:2, pp 24-34. Diamond, W. D. 1988. The Effect of Probability and Consequence Levels on the Focus of Consumer Judgements in Risky Situations, in Journal of Consumer Research, 15, September, pp 280-283. 22 Dorfman, P.W. & Howell, J.P. (1988). Dimensions of national culture and effective leadership patterns: Hofstede revisited. Advances in International Comparative Management, 3, 127-150. Dowling, G.R. and R. Staelin, 1994. A Model of Perceived Risk and Intended RiskHandling Activity, in Journal of Consumer Research, 21, June, pp 119-134. Dubois, A., Hulthén, K. & Pedersen, A-C. 2004. Supply Chains and Interdependence: A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Vol. 10, pp 3-9. Erez, M., and Gati, E. (2004). A Dynamic, Multi-level Model of Culture: From the Micro Level of the Individual to the Macro Level of a Global Culture, in Applied Psychology: An International Review, Vol. 33 (4), pp 583-612. Ettlinger, N. 2003. Cultural Economic Geography and a Relational and Microspace Approach to Trusts, Rationalities, Networks, and Change in Collaborative Workplaces, in Journal of Economic Geography, 3, pp 145-171. Fearne, A., Hughes, D. and R. Duffy, 2001. Concepts of Collaboration – Supply Chain Management in a Global Food Industry, in Food and Drink Supply Chain Management – Issues for the Hospitality and Retail Sectors, Eds. Eastham, Sharples and Ball, Butterworth Heinemann, London. Giannakis, M., Croom, S., and N. Slack, 2004. Supply Chain Paradigms, in Supply Chains, Concepts, Critiques and Futures, Eds. S. New and R. Westbrook, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Goodstein, L.D. (1981). American business values and cultural imperialism. Organisational Dynamics, 10,1, 49-54. Greatorex, M., V-W Mitchell and R. Cunliffe. 1992. A Risk Analysis of Industrial Buyers - The Case of Mid Range Computers, in Journal of Marketing Management, 8, pp 315-333. Hampden-Turner, C. & F. Trompennars, (1993). The Seven Cultures of Capitalism: Value systems for creating wealth in the United States, Britain, Japan, Germany, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands, Doubleday: New York. Harland, C., Knight, L., and P. Cousins, 2004. Supply Chain Relationships, in Supply Chains, Concepts, Critiques and Futures, Eds. S. New and R. Westbrook, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 209-227. Hawes, J.M. and S. H. Barnhouse. 1987. How Purchasing Agents Handle Personal Risk, in Industrial Marketing Management, 16, pp 287-293. Hofstede, G.H. (1980). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Workrelated Values, Sage: London. 23 Hofstede, G.H. (1994). Cultures and Organisations: Intercultural Cooperation and its Importance for Survival. McGraw Hill: London. Hofstede, G.H. (1997). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGrawHill: New York. Hofstede, G.H. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviours, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Sage: Thousand Oaks. Hornibrook, S. A., and A. Fearne, 2001. Managing Perceived Risk: A multi-tier case study of a uk retail beef supply chain, in Journal on Chain and Network Science, Vol. 1:2, pp 87-100. Hornibrook, S.A. 2002. The Management of Perceived Risk in the Food Industry: A Case Study of the UK Beef Supply Chain. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of London. Hornibrook, S.A., and A. Fearne, 2003. Managing Perceived Risk as a Marketing Strategy for beef in the UK Foodservice Industry, International Food and Agribusiness Management Review Vol. 6:3. House, R. J. & Hanges, P. J. & Javidan, M. & Dorfman, P. W. & Gupta, V. & Globe Associates (Eds) (2002). Cultures, Leadership, and Organizations: Globe: a 62 Nation Study / Vol. 1. Sage: Thousand Oaks. Hunt, J.W. (1981). Applying American behavioural science: Some cross-cultural problems. Organisational Dynamics, 10, 1, 55-62. Jiang, B. 2002. How International Firms are Coping with Supply Chain Issues in China in Supply Chain Management: An International Journal. Vol. 7:4, pp 184-188. Joffe, H. 2003. Risk: From Perception to Social Representation, in British Journal of Social Psychology, Vol.42, pp 55-73. Kim, U. (2000). Indigenous, cultural, and cross-cultural psychology: A theoretical, conceptual, and epistemological analysis. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 3, 265287. Lamming, R., Caldwell, N., and W. Phillips, 2004. Supply Chain Transparency, in Supply Chains, Concepts, Critiques and Futures, Eds. S. New and R. Westbrook, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 191-207. Lui, H, and Y. P. Wang, 1999. Co-ordination of international channel relationships: four case studies in the food industry in China, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Vol. 14:2, pp. 130-150. March, J.G. and Z. Shapira. 1987. Managerial Perspectives on Risk and Risk Taking, in Management Science, 33:11, pp1404-1418. 24 Mattson, L-G. 2003. Reorganisation of Distribution in Globalisation of Markets: The Dynamic Context of Supply Chain Management, in Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol.8:5, pp 416-426. McGrew. A. G., 1992. Conceptualising global politics. In Global Politics: Globalisation and the National State, eds. A. G. McGrew and P. G. Lewis. The Polity Press, Cambridge. Mitchell, V.-W. 1998. Segmenting Purchasers of Organisational Professional Services: A Risk-Based Approach, In Journal of Services Marketing, 12:2, pp 83-97. Motarjemi, Y., and F.K. Kaferstein, 1997. Global Estimation of Foodborne Diseases, in World Health Statistics Quarterly, Vol. 50:1/2 pp 5-11. Murray, K.B., and J.L. Schlacter, 1990. The Impact of Services versus Goods on Consumers' Assessment of Perceived Risk and Variability, in Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 18(1), pp 51-65. Nassimbeni, G. 2004. Supply Chains: A Network Perspective, in Supply Chains, Concepts, Critiques and Futures, Eds. S. New and R. Westbrook, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 43-65. New, S. 1996. A Framework for Analysing Supply Chain Improvement, in International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 16:4, pp 1934. New, S. 2004. Supply Chains: Construction and Legitimation, in Supply Chains, Concepts, Critiques and Futures, Eds. S. New and R. Westbrook, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 69-108. New, S. 2004b). The Ethical Supply Chain, in Supply Chains, Concepts, Critiques and Futures, Eds. S. New and R. Westbrook, Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 253-280. Northen, J., 2000. Farm Assurance Schemes in the United Kingdom Livestock Sector: Their use as Quality Signals. Unpublished PhD Thesis. University of Reading. Ogbonna, E. and Harris, L.C. (2002). Organizational culture: a ten-year, two-phase study of change in the UK food retailing sector. Journal of Management Studies, 39, 2, 673-706. Peters, M.P., and M. Venkatesan, 1973. Exploration of Variables Inherent in Adopting an Industrial Product, in Journal of Marketing Research, Vol.X, pp 312-5. Prasad, S. and J. Sounderpandian, 2003. Factors Influencing Global Supply Chain Efficiency: Implications for Information Systems, in Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 8:3, pp 241-250. 25 Reber, G. & Jago, A.G. & Auer-Rizzi, W. & Szabo, E. (2000). Führungsstile in sieben Ländern Europas - Ein interkultureller Vergleich. In: Regnet, E. & Hofmann, L.M. (Eds). Personalmanagement in Europa. Göttingen: Verlag für Angewandte Psychologie. Robertson, C.J. and W. F. Crittenden, 2003. Mapping Moral Philosophies: Strategic Implications for Multinational Firms, in Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 24, pp 385-392. Robinson, R.V. (1983). Geert Hofstede: Cultures’ consequences: International differences in work-related values. Work and Occupations, 10, 110-115. Schiffman, L. G., and L. L. Kanuk, 1994. Consumer Behaviour. 4th Ed. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. Schein, E.H. (1989). Organizational Culture and Leadership, Jossey-Bass: San Francisco. Schein, E.H. (1990). Organisational Culture, American Psychologist, 45, 2, 109-119. Schneider, S.C. and Barsoux, J-L (2003). Managing Across Cultures (2nd Edition). Financial Times Prentice Hall: Harlow. Schwartz, S. H., and Boehnke, K. (2004). Evaluating the structure of human values with Confirmatory Factor Analysis, in Journal of Research in Personality, 38 pp 230255. Slovic, P., Fischoff, B. and Lichenstein, S. (1980). Facts and Fears: Understanding Perceived Risks, in Schwing, R. and Albers, W. Jr (Editors), Societal Risk Assessment: How Safe IS safe Enough? Plenum, New York, pp 181-216. Smith, P.B., Peterson,. M.F., and Schwartz, S.H. (2002). Cultural Values, Sources of Guidance and Their Relevance to Managerial Behaviour: A 47 Nation Study, in Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33, pp 188-208. Snow, C.C.; Canney Davison, S.; Hambrick, D.C. and Snell, S.A. (1993). Transnational Teams – A Learning Resource Guide, ICEDR Report, 30. Sondergaard, M. (1994). Research note: Hofstede’s consequences: A study of reviews, citations and replications. Organisational Studies, 15, 447-456. Stahl, G.K. (2001). Management der sozio-kulturellen Integration bei Unternehmenszusammenschlüssen und –übernahmen. Die Betriebswirtschaft. Vol. 61/1. Sweeney, J. C., G. N. Soutar, and L. W. Johnson. 1999. The Role of Perceived Risk in the Quality Value Relationship: A Study in a Retail Environment, in Journal of Retailing, 75(1), pp 77-105. Tayeb, M (1988). Organisations and National Culture. London: Sage. 26 Trompenaars, F. (1993). Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Business, Economist Books: London Varzakas T., and D. Jukes, 1997. Globalisation of food quality standards: the impact in Greece, in Food Policy, Vol. 22:6, pp 501-514. Weaver, G.R. 2001. Ethics Programs in Global Businesses: Culture’s Role in Managing Ethics, in Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 30, pp 3-15. Weick, K.P. (1985). The significance of corporate culture, in P. Frost, L.F. Moore, M.R. Louis, C.C. Lundberg and J. Martin (Eds.) Organizational Culture, Sage: California, pp. 381-90, p.382. Whipp, R., Rosenfeld, R. and Pettigrew, A. (1989). Culture and competitiveness: evidence from two mature UK industries. Journal of Management Studies, 26, 6: 561585. Wilkins, A. & Ouchi, W. (1983). Efficient Cultures: Exploring the Relationship Between Culture and Organizational Performance. Administrative Science Quarterly. Vol. 28. World Health Organisation, 2003, Food Safety and Foodborne http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs237/en/, accessed 3 June 2004. World Trade Organisation, 2003. The WTO – in Brief http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/inbrief_e/inbr00_e.htm, June 2004. Illness, accessed 3 Yeow, P.M.N. (2000). Individual and Organisational Change Management Strategies: A proposed framework drawn from comparative studies in Complexity theory and models of stress and well-being. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Sheffield, UK. Yeow, P.M.N. (2002). Complexity Theory and its relevance to Changing Organisations: A cross-cultural study in Singapore. Shogaku Ronsan (a publication by the Society of Business and Commerce in Chuo University, Japan), XLV, 2: 95-116. Yeung, R.M.W., and J. Morris 2001. “Food Safety Risk: Consumer Perception and Purchase Behaviour”, British Food Journal, Vol.103, No.3, p.170-186. Zwart, A.C., and Mollenkopf, D. A. 2000. Consumers’ Assessment of Risk in Food Consumption: Implications for Supply Chain Strategies, 4th International Conference on Chain Management in Agribusiness and the Food Industry, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 25-26 May. 27 28