Supplementary material for “No evidence that sperm morphology predicts paternity success in

wild house wrens.” ERA Cramer, T Laskemoen, O Kleven, K LaBarbera, IJ Lovette, and JT

Lifjeld. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology.

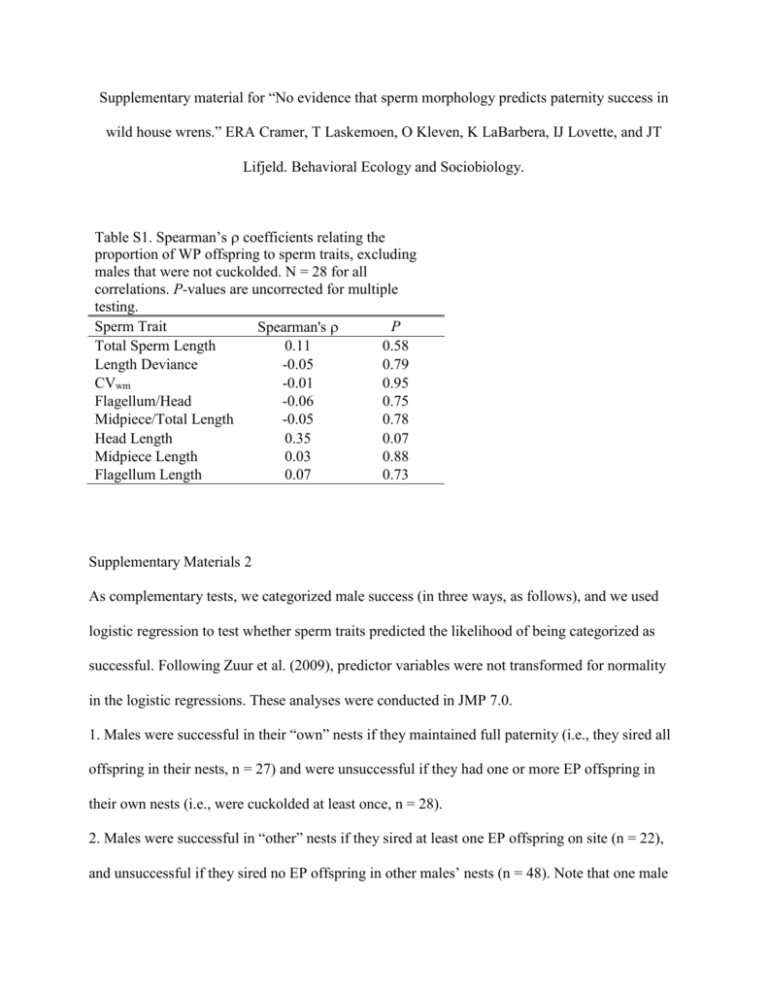

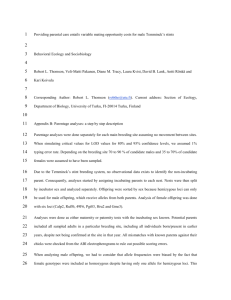

Table S1. Spearman’s coefficients relating the

proportion of WP offspring to sperm traits, excluding

males that were not cuckolded. N = 28 for all

correlations. P-values are uncorrected for multiple

testing.

Sperm Trait

P

Spearman's

Total Sperm Length

0.11

0.58

Length Deviance

-0.05

0.79

CVwm

-0.01

0.95

Flagellum/Head

-0.06

0.75

Midpiece/Total Length

-0.05

0.78

Head Length

0.35

0.07

Midpiece Length

0.03

0.88

Flagellum Length

0.07

0.73

Supplementary Materials 2

As complementary tests, we categorized male success (in three ways, as follows), and we used

logistic regression to test whether sperm traits predicted the likelihood of being categorized as

successful. Following Zuur et al. (2009), predictor variables were not transformed for normality

in the logistic regressions. These analyses were conducted in JMP 7.0.

1. Males were successful in their “own” nests if they maintained full paternity (i.e., they sired all

offspring in their nests, n = 27) and were unsuccessful if they had one or more EP offspring in

their own nests (i.e., were cuckolded at least once, n = 28).

2. Males were successful in “other” nests if they sired at least one EP offspring on site (n = 22),

and unsuccessful if they sired no EP offspring in other males’ nests (n = 48). Note that one male

was included as successful in other nests, but not in the continuous analyses presented in the main

text, because he was involved at one nest where rapid mate-switching and EP paternity could not

be distinguished with certainty; this nest was excluded for both EP and WP success measures.

This male did, however, also sire EP offspring at a nest with a confidently-assigned WP sire.

3. Males that sired all offspring in their own nests may not have faced sperm competition if their

females did not mate multiply. Males that sired no EP offspring could have failed to attract EP

females for copulation. We attempted to disentangle these processes from PCSS by restricting the

data set to males whose sperm was known to have been in competition, because they sired

offspring in mixed-paternity broods. Within this subset, males that gained EP paternity in other

nests and maintained full paternity in their own nests were considered successful (n = 10), and

males that lost WP paternity without gaining EP offspring in other nests on site were considered

unsuccessful (n = 21).

Literature Cited:

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker NJ, Saveliev AA, Smith GM (2009) Mixed effects models and

extensions in ecology with R. Springer, New York.

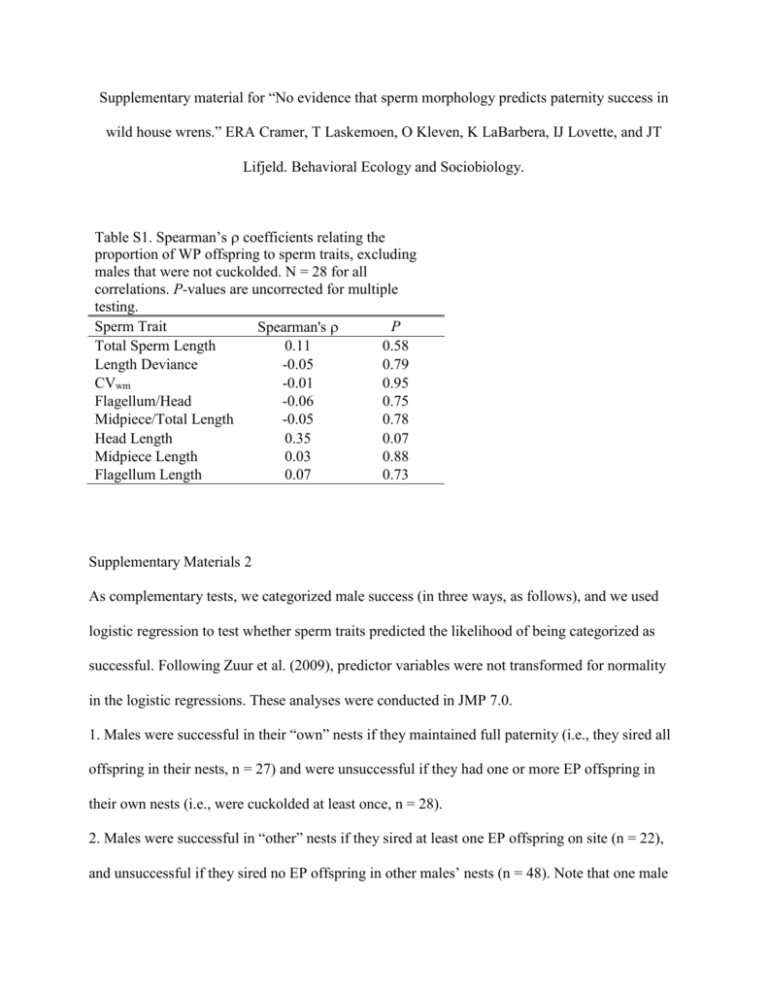

Table S2. Comparisons of sperm traits in relation to performance in post-copulatory

sexual selection. Males that were not cuckolded were successful in their “Own” nests.

Males that sired at least one EP offspring on-site were successful in “Other” nests. Males

that gained EP offspring in other nests without losing WP paternity were successful in

“Both” nests. The χ2 test statistic describes the probability of success; means for each

group are given for completeness, with CVwm expressed as a percent.

Mean ± SE for males

Nest

Log odds of “success,”

Successful

Unsuccessful

Sperm trait

Type

Test statistic (P)

2

Own

-0.10 ± 0.08, χ 1 = 1.60 (0.21)

77.19 ± 0.68 78.48 ± 0.73

Total Sperm

2

Other

-0.05 ± 0.07, χ 1 = 0.44 (0.51)

77.48 ± 0.70 78.13 ± 0.58

Length

2

Both

-0.08 ± 0.10, χ 1 = 0.53 (0.47)

77.94 ± 1.12 78.99 ± 0.85

Own

-0.04 ± 0.11, χ21 = 0.15 (0.70)

2.73 ± 0.50

2.99 ± 0.46

Length

2

Other

-0.12 ± 0.12, χ 1 = 0.98 (0.32)

2.44 ± 0.41

3.06 ± 0.38

Deviance

2

Both

-0.12 ± 0.18, χ 1 = 0.49 (0.48)

2.51 ± 0.68

3.16 ± 0.56

2

Own

0.03 ± 0.22, χ 1 = 0.02 (0.90)

2.98 ± 0.23

2.94 ± 0.25

2

CVwm

Other

-0.04 ± 0.20, χ 1 = 0.04 (0.84)

2.88 ± 0.31

2.94 ± 0.18

Both

0.11 ± 0.31, χ21 = 0.14 (0.71)

3.03 ± 0.47

2.86 ± 0.25

2

Own

-0.18 ± 0.76, χ 1 = 0.05 (0.81)

5.19 ± 0.07

5.22 ± 0.07

Flagellum/

2

Other

-0.10 ± 0.73, χ 1 = 0.02 (0.90)

5.20 ± 0.08

5.21 ± 0.05

Head

2

Both

0.18 ± 0.98, χ 1 = 0.03 (0.85)

5.29 ± 0.15

5.26 ± 0.08

2

Own

10.07 ± 6.73, χ 1 = 2.24 (0.13)

0.66 ± 0.01

0.64 ± 0.01

Midpiece/

Other

-9.33 ± 6.41, χ21 = 2.12 (0.15)

0.64 ± 0.01

0.65 ± 0.01

Total Length

2

Both

-0.93 ± 9.23, χ 1 = 0.01 (0.92)

0.64 ± 0.02

0.65 ± 0.01

2

Own

-0.36 ± 0.42, χ 1 = 0.75 (0.39)

12.52 ± 0.14 12.68 ± 0.12

2

Head Length

Other

-0.15 ± 0.41, χ 1 = 0.14 (0.71)

12.56 ± 0.16 12.62 ± 0.08

Both

-0.34 ± 0.52, χ21 = 0.43 (0.51)

12.48 ± 0.31 12.67 ± 0.14

2

Own

0.04 ± 0.08, χ 1 = 0.27 (0.60)

50.60 ± 0.66 50.10 ± 0.73

Midpiece

2

Other

-0.13 ± 0.07, χ 1 = 3.06 (0.08)

49.39 ± 0.75 51.00 ± 0.50

Length

2

Both

-0.06 ± 0.10, χ 1 = 0.30 (0.58)

50.12 ± 1.28 50.93 ± 0.83

2

Own

-0.10 ± 0.08, χ 1 = 1.38 (0.24)

64.67 ± 0.63 65.80 ± 0.71

Flagellum

2

Other

-0.05 ± 0.07, χ 1 = 0.40 (0.53)

64.92 ± 0.66 65.50 ± 0.56

Length

Both

-0.07 ± 0.11, χ21 = 0.40 (0.53)

65.46 ± 1.01 66.32 ± 0.81

Figure S1.

Figure S1. Relationships between sperm traits and three measures of success in post-copulatory

sexual selection, with 2009 samples in black, 2010 in grey, and 2011 in white. Columns: left,

proportion of within-pair (WP) young sired; middle, number of extra-pair (EP) young sired in

other males’ nests; right, annual reproductive success. Rows (numbered top to bottom): 1, Total

sperm length; 2, length deviance; 3, within-male variation in total length; 4, flagellum/head ratio;

5, midpiece/total sperm length ratio. For statistical tests, see Table 2 and Table S2.