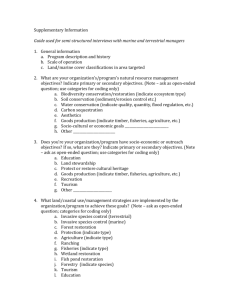

1 Information and Background

advertisement