2011 - East Carolina University

advertisement

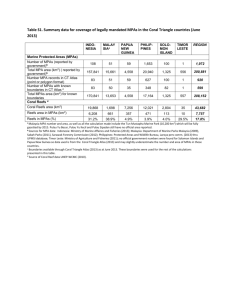

1 Should North Carolina Develop Marine Protected Areas Along our Coast? Current Topics in Coastal Biology – Topic 2 East Carolina University Spring 2011 Abstract - Class Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are areas in the marine environment with governmental regulations restricting access and exploitation of natural and cultural resources. MPAs can have both positive and negative effects. Many MPAs fail while others are successful, but the metric for measuring success or failure is unclear and changes with the intent of each MPA. North Carolina has many managed areas throughout the estuarine, near-shore and offshore environment and it is unclear whether the complications and expenses of creating MPAs in North Carolina waters would outweigh the expected benefits. _______ 1 This review paper presents the views of the students enrolled in the Current Topics in Coastal Biology course and in no way reflects the views or position of East Carolina University. 2 Overview – Victoria Autry, Liz Brown-Pickren, Heather Waters A marine protected area (MPA) is defined as an area where natural and/or cultural resources are given greater protection than the surrounding waters according to www.mpa.gov (2011). These areas can range from the deep ocean to estuaries and sounds. They are put into place for many reasons but mostly to maintain or restore the intrinsic biodiversity and natural processes occurring in a specific area. They also provide recreation and economic opportunities for Americans, help sustain critical habitats, and protect areas from human impact. One of the positive aspects of marine reserves is that they can be applied widely and that they are proactive rather than reactive. MPAs can have great ecological and biological advantages but the socioeconomic aspects must also be addressed. Stakeholders in coastal communities, such as commercial fishermen, consumers of local seafood, recreational fishermen can be negatively affected by MPAs. Furthermore, MPAs are expensive to start up and maintain and the costs must be balanced against the benefits. Currently the United States has 1,619 MPAs in place and about 40% of all US waters are in some form of an MPA (http://www.mpa.gov/pdf/helpful-resources/us_mpas_snapshot.pdf). The majority of these are located within the Virginian Atlantic marine ecoregion (Figure 1). Almost all (86%) of the nation’s MPAs are multiple use sites and very few are “no take” areas, defined as “MPAs or zones that allow human access and even some potentially harmful uses, but that totally prohibit the extraction or significant destruction of natural or cultural resources” (Executive Order 13158). Less than 1% of the country’s waters are considered no-take making them relatively rare in the U.S (Figure 2). Figure 1. Marine protected Areas (MPAs) within the US EEZ and US territories. http://www.mpa.gov/pdf/helpful-resources/us_mpas_snapshot.pdf). 3 Figure 2. Almost all (86%) of our nation’s MPAs are multiple-use sites that allow a variety of human activities, including fishing and other extractive uses. In contrast, only 14% of all U.S. MPAs are no take areas that prohibit the extraction or significant destruction of natural or cultural resources. The size of multiple-use and no-take MPAs shows even stronger contrast. In most states and regions, no-take MPAs cover only a small fraction of the area of multiple-use MPAs. Less than 3% of the area in MPAs in the U.S. is no-take. No-take MPAs occupy only 1% of all U.S. waters. (http://www.mpa.gov/pdf/helpful-resources/us_mpas_snapshot.pdf. There are almost 5,000 marine protected areas worldwide that cover nearly 2.4 million square kilometers or 0.65% of the world’s oceans (MPA Global 2005). The effectiveness of MPAs is controversial because while some studies show biological benefits, other studies show that there are underlying negative economic issues such as expense and a failure rate of management goals of up to 90% (Christie et al. 2003). Small isolated protected areas are cited as having conservation value while other perspectives claim that small MPAs have little or no benefit; that they must be included in a large network of protected areas to be effective. Some studies show benefits will occur only when 12% (Fuller 2010) to 30% (Balmford 2004) of the world’s ocean is protected by MPAs. Currently only a small fraction of the world’s ocean is protected (Figure 3). 0 0 - 0.1 0.1 - 0.25 0.25 - 0.5 0.5 - 1 1-2 2-5 5 - 10 10 - 20 20 - 40 > 40 Map created by: Louisa Wood, Sea Around Us Project, University of British Columbia, March 2006 Source: MPA Global, October 2005 4 Figure 3. “The World Parks Congress target of creating a global system of MPA networks by 2012 - including ‘strictly protected areas’ amounting to at least 20-30% of each habitat will not be reached until at least 2085 at the current rate of global MPA designation. The 2085 date in itself represents a best-case scenario that is unlikely to occur and assumed that all MPAs – both future and existing – will be ‘no-take’” (Wood et al. 2005). A 2004 study of the costs of starting and maintaining a global MPA network of 20-30% of the seas would cost $5-19 billion per year to run but would increase the sustainability of the global marine fish catch, worth $70-80 billion per year. “It would also help ensure the continued delivery of largely unseen marine ecosystem services with a gross value of… $4.5-6.7 trillion each year” (Balmford 2004). Even the level of protection in the strictest of MPAs, the “National Sanctuary System” in the United States, varies. For example, the channel carefully designed to allow ships to navigate through the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary and avoid disrupting right whale communication is ineffective (Figure 4; Allen 2011). Figure 4. Depiction of how ship passage through the Stellwagon Bank National Marine Sanctuary affects whale communication. Some stakeholders object to being excluded from MPAs. Commercial fishing is essential to the economies of coastal communities of North Carolina, with 69 million pounds of seafood worth $77 million dollars having been landed in 2009 (NCDMF 2010). No-take areas exclude fishermen from traditional grounds and cause them to travel further to fish, increasing maintenance and fuel costs (Gell and Roberts 2003). Biological Implications - Coley S. Hughes, Joshua Whaley, Jeff Dobbs MPAs can play an important role in the preservation and restoration of marine ecosystems as well as serve as effective fisheries management tools. Goñi et al. (2008) and 5 Stelzenmüller et al. (2009) show evidence that significant export of biomass is possible under optimal conditions and can have a positive effect on the fisheries that exploit the surrounding waters. There appears to be a growing consensus that MPAs may be able to produce at least the level of sustainable yield that is possible with traditional single species management (Hastings and Botsford 1999, Halpern 2003). MPAs may require more intensive planning and study of the marine ecosystems they seek to protect than methods that have been used historically. In order to function effectively, well planned sound ecological principles must be taken into account (Rabaut et al. 2009). Life history, larval dispersion and placement to maximize benefit to both ecosystems and human populations must be considered if these areas are to produce tangible benefits (Cudney-Bueno et al. 2009). These are all significant challenges facing the implementation of Marine Protected Areas in North Carolina. Marine environments are generally more open and present much fewer barriers to species dispersal than terrestrial systems. Currents, upwelling and other factors facilitate the special distribution of species (Planes et al. 2006). These characteristics suggest that the protection of healthy, productive ecosystems from mortality and environmental degradation by fishing and other extractive uses should result in positive effects in biomass outside the reserve areas. This “spillover” effect is both a major reason for the establishment of MPAs as well as a major source of debate regarding their effectiveness. The protection of significant areas in North Carolina has the ability to positively affect the conservation of species and entire ecosystems for their own sake, while also providing a tool for the sustainable management of fish stocks (Hastings and Botsford 1999). The ecosystems that benefit from protection, either directly or through spillover effects from nearby areas, have the potential to provide other biological impacts to surrounding communities (Balmford et al. 2004). The spillover effect has been documented by way of significant increases in catch per unit effort in areas adjacent to MPAs in many separate studies conducted all across the world (Gell and Roberts 2003). This spillover effect is a key benefit, which allows the surrounding commercial and recreational fisheries to benefit from the presence of the no-take area. Increases in the catch per unit effort observed in areas surrounding no-take MPAs are a byproduct of the numerous other increases in biological measures occurring within the reserve. A meta-analysis of over 100 studies done on as many different MPAs showed that the vast majority of MPAs sampled had significant increases in density, biomass, size and diversity of organisms within an MPA (Figure 5). This included every trophic level as well as vertebrates and invertebrates (Halpern 2003). 6 Figure 5. Differences in biological measures (density [no./ area], biomass [mass/area], mean size of organism, and diversity total species richness]) between inside a reserve and outside a reserve (or after vs. before) for all organisms (A). The numbers of independent reserve measurements that were associated with each trend are plotted for each biological measure: white bars represent lower values inside the reserve, gray bars represent no difference between reserve and nonreserve areas, and dark bars represent higher values inside the reserve. P values above the bars are significance values for chi-square tests values for chi-square tests of differences between frequencies among observations (null hypothesis: no difference in frequency); NS, not significant (Halpern 2003). Ecological models predict that the implementation of protected areas should lead to harvestable production that is at least equal to traditional single species management practices (Gaylord et al. 2005, Hastings and Botsford 1999). Most targeted fish species exhibit a larval stage in the life histories in which individuals are subject to wide spread dispersion throughout the range (Gaylord et al. 2005). Larval dispersal from MPAs should seed the outlying sections of coastline, allowing a sustainable harvest based on the removal of a certain percentage of productive habitat from fishing pressure. This ecologically based approach to fisheries management contrasts with the more traditional method of allowing a certain percentage of the population of a target species to be harvested (Hastings and Botsford 1999). Some argue that in order for a no-take MPA to be successful, it must be so large that it is uneconomical to manage, and it restricts the commercial and recreational fisheries in such a manner that it does more harm than good. This assumption that the size of the no take zone must be huge is simply untrue. Halpern (2003) found that success of an MPA in creating the desired biological effects is independent of reserve size. The important factor in designing the MPA is that it is strategically placed in a critical area such as a spawning area for one of the species being sought to be protected. As long as this critical area is protected, organisms of interest within the MPA will be able to grow in biomass and increase their reproductive rate compared to outside the reserve (Gell and Roberts 2003). However, the establishment of marine protected areas by itself will likely not be enough to achieve the results without the continued implementation and management of fishing grounds and the fishing industry (Planes et al. 2006). Goñi et al. (2008) and Stelzenmüller et al. (2009) 7 found that biomass and functional diversity declined in proportion to the distance from the protected areas, which indicates that MPAs on their own, without continued ecology based management, may not be sufficient. Areas outside reserves must also be regulated to avoid creating ecological “islands” surrounded by such intense fishing that spillover is effectively stopped at the border. While this may be beneficial to fishing fleets in the short term, it may undermine the full potential of MPAs to restore marine ecosystems. A common criticism of MPAs is that they are breeding grounds for undesirable invasive species such as the Indo-Pacific Lionfish, whose population has been estimated at over 1000 individuals per acre in some areas along the southern part of the Eastern Seaboard (NOAA 2010). These fish occupy similar niches of many local reef fish, resulting in population loss along several trophic levels. Another non-native invasive species, the Japanese Shore Crab, is slowly making its way down the coast from New England and has been overtaking local crab populations as far south as North Carolina. This crab is omnivorous, often feeding upon small mollusks, and lives among sensitive oyster beds. There is much speculation that these crabs are responsible for the declining blue crab population in the Chesapeake Bay and American lobster populations farther up the coast (Benson 2011). When planning for MPAs, ensuring the success of local species is critical and should be planned in concert with invasive species control. Social Aspects of MPAs - Dan Zapf, Meghan Lell , Evan Knight Typically the groups most affected by the creation of marine protected areas are those that rely directly on marine resources for their income. These groups include, but are not limited to, commercial fishermen, dive tour operators and fishing and site seeing guides. All of these groups have reasons why they would be for or against the creation of marine reserves, but commercial fishermen are generally considered to be the group with the most to lose from the creation of marine reserves; often they are the most vocal about the negative impacts of marine reserves. However, in many instances commercial fishermen have been open minded about the creation of marine reserves. Brody (1996) conducted a survey of groups concerning the creation of marine reserves in the Gulf of Maine; among these were commercial and recreational fishermen. Commercial fishermen acknowledged that current harvest practices were unsustainable and agreed the creation of marine reserves could be beneficial in protecting vulnerable fish stocks (Brody 1996). These thoughts are similar to those presented by Grader and Spain (1999) who wrote on behalf of the Pacific Coast Federation of Fisherman’s Associations. Commercial fishermen recognize that their livelihood is based on the health of fish populations and marine reserves are could be beneficial to fish stocks (Grader and Spain 1999). The findings of Brody (1996) and Grader and Spain (1999) suggest that fishermen want to be included in the process of establishing marine reserves and want the establishment of reserves to be based on a combination of their knowledge and science. In some cases commercial fishermen were not totally opposed to the idea of MPAs and had reason to believe that the establishment of MPA would benefit their bottom line (Grader and Spain 1999). The main thing that commercial fishermen want is to be heard by officials in charge of making decisions for the designation areas of the MPAs (Grader and Spain 1999). The 8 establishment of the Quirimbas National Park, a marine reserve in Mozambique, is an example of a reserve that incorporated local ecological knowledge in its creation. This reserve was created with input from local subsistence fishermen in order to allow them to continue fishing in traditional locations while still protecting essential habitat (Bechtel 2002). Fisheries management can be a complicated process, particularly when multiple species are being managed with different sets of regulations restricting size limits, gear types and open seasons. The establishment of marine reserves can help to simplify management (Crowder et al. 2000), and enforcement of regulations (Bohnsack 1996), because the establishment of marine reserves provides a specific area in which regulations can be targeted. In addition, Mangel (2000) found that protecting habitat was more effective than managing for maximum sustainable yield. In North Carolina the creation of marine protected areas may be necessary under the Endangered Species Act. Section 7B of the North Carolina estuarine striped bass fishery management plan summarizes the interaction of the striped bass fishery with threatened and endangered species. The FMP describes endangered species and their protection under the Endangered Species Act. Endangered Species Act provides a mean where ecosystems used by endangered species can be conserved, and also prohibits collection or harassment of endangered or threatened species. The endangered shortnose sturgeon, Kemp’s Ridley turtle, hawksbill sea turtle, leatherback sea turtle, and the threatened green sea turtle and loggerhead sea turtle are all found in North Carolina Waters and have been caught as bycatch in fishing gears. Despite being highly migratory these species may benefit from the creation of marine reserves that protect critical habitat (NCDMF 2011). While some commercial fishing communities appear to be cautiously supportive of marine reserves, this is not an all-encompassing view. Sumas et al. (1999) found commercial fishermen to be strongly against the creation of marine reserves in the Florida Keys. Commercial fishermen as well as dive tour operators both felt alienated in the process of establishing marine reserves. Specifically commercial fishermen felt the alienated in deciding the placement of marine reserves and that they had the most to lose from the establishment of reserves. Sumas et al. (1999) concluded that communication between managing agencies and user groups is essential for building trust and support for the establishment of reserves. Inadequate communication between groups will lead to reserves that are ineffective in accomplishing their purpose, a statement that is supported by Bechtel (2002). White House Executive Order 13158 for MPAs states that the purpose is to “protect the natural and cultural resources within the marine environment for the benefit of present and future generations” (Executive Order 13158). MPAs are created to help sustain and enhance our marine resources. As mentioned earlier fishermen understand the consequences of overfishing; their livelihoods depend on it (Grader and Spain 1999). However, fisherman have a problem with MPAs because, there are a lot of unknown questions that still need to be addressed in regards to how effective MPAs really are (Grader and Spain 1999). Fishermen want to protect their resources; they are not for sure if an MPA is the correct way to go about conservation. Commercial fishermen are blamed for the overexploitation of marine resources (Grader and Spain 1999). They also suffer most of the negative impacts of MPAs. Fishermen will have to bear all the costs, even though they may not benefit from an established MPA. There are two 9 cases that can happen after an MPA is established. Either the fishermen will benefit from the MPA because there will be an increase in the catch levels, or fishermen will gain nothing because the catch level will remain unchanged. Whether there is an increase catch level depends on factors such as how high the catch level was before the MPA was created, whether an increase in the status quo of the catch level has to occur, and there has to be a biological link between the insides and outsides of the MPA (Sanchirico 2000). There are many potential costs to fishermen that can be associated with an MPA being establishment on North Carolina’s coast. MPAs will decrease the amount of area available for fishing, which could cause congestion of fishing ships in the water. Congestion can lead to an “increase in fuel usage, crew employment, and higher capital cost” (Sanchirico 2000). Problems could occur, causing higher competition of the second species, and conflict with fishing gear (Sanchirico 2000). Commercial fishermen are not the only ones who have a high interest in MPAs; recreational fishermen are also concerned with the MPAs. There are thousands of recreational fishermen in North Carolina that provide millions of dollars in revenue. The best interests for recreational fishermen are to have greater numbers and larger more fecund fish, and MPAs accomplish both of these interests. Marine protected areas increase the density and size of fish and produce larger more fecund females (Roberts et al. 2001). For the most part recreational fishermen approve of Marine Protected Areas. In an interview in the North Carolina Sportsman, Mike Nussman, president and CEO of the American Sportfishing Association, said, “For decades, the sport fishing industry and anglers themselves have supported efforts to improve our Nation’s fisheries. These MPAs were created using a public process, driven by sound science, which took into account the economic and social impacts their creation will have in South Atlantic.” (American Sportfishing Association 2009). Other stakeholders in this debate are coastal business owners as well as tourist and residents. Ecotourism could be increased after the establishment of a MPA. Activities such as snorkeling and scuba diving could generate more revenue for the state’s coastal tourism industry. (Sanchirico 2000). North Carolina has management plans already in place for coastal fisheries and the natural resources that support them. The Coastal Habitat Protection Plan (CHPP) was established to provide gaps on important fish habitats. The CHPP also states that better rule enforcement and management coordination will help benefit the fish habitats. Several federal and state agencies that are involved with marine protection are also working within the ideas of the CHPP. These agencies include the Department of Environmental and Natural Resources, which houses the Division of Marine Fisheries, the Marine Fishers Commission, the Environmental Management Commission, and the Coastal Resources Commission (Easley and Ross 2005). Economic Considerations- Jessie Hathaway, Barryn McLaughlin, Kimberly Wade We must also consider the associated economical costs of Marine Protected Areas. Recreational fishermen spend more than 1.6 billion dollars in North Carolina pursuing their 10 sport. The average estimated amount spent on offshore fishing per trip is $971 (Crosson 2010). Decreasing the area fishermen are allowed to fish in will proportionately lower the revenue from this industry, affecting bait shops and charter boat captains. Additionally, most of the economic gains from this industry are distributed in rural and coastal locations where there are limited job opportunities. Commercial fishermen frequenting the area will likely be forced to travel farther to catch their daily limit. Consequently, the local seafood restaurants and buyers will also be forced to increase their prices. To give an example of the impact on stakeholders , in 2002, the value of the Southern flounder fishery alone in North Carolina was over $59 million. The Atlantic Menhaden fishery had a value of over $40 million. On any given day in 2002, there were approximately 89 dealers, 493 fishermen and 616 vessels harvesting 367, 424 pounds of catfish worth a little over $1.8 million (Burgess and Bianchi 2002). Maintenance costs must also be factored into the total cost of Marine Protected Areas. The median cost of maintaining an MPA per square kilometer is $8,976 per year in the United States (Balmford 2004). This cost must be covered by additional taxes. Alternatives – Justin Bohannon, Hillary Huffer, Jake Pridgen Alternatives to No-take MPAs in North Carolina include other possible MPA protection levels (i.e., Multiple Use, No-access), as well as the absence of an MPA altogether. This section will explain the various levels of MPA protection and their implications. Additionally, the current management guidelines in North Carolina are explored, which would solely govern the areas if no MPA were put in place. “Multiple Use Marine Protected Areas allow a variety of human activities that are managed comprehensively to support compatible uses while protecting key habitats and resources. Protections may be uniform across the MPA or allocated spatially or temporally through marine zoning to reduce user conflicts and minimize adverse impacts,” (Wahle 2003). Multi-use MPAs are the most common type of MPA in the United States. They also include most marine sanctuaries, national and state parks, and many fisheries and cultural resource MPAs (Wahle 2003). IUCN categorizes the multi-use areas as an, “Area managed mainly for sustainable use of natural ecosystems e.g. multiple-use protected area such as Mafia Island Marine Park, Tanzania,” (Anonymous n.d.). These MPAs are usually applied over large areas, which allow for integrated management of complete marine ecosystems, usually through a zoning process (National MPA Center 2010). There are three types of multiple-use MPA’s, including: Uniform Multiple Use, Zoned Multiple Use, and Zoned Multiple Use with No Take Areas (NOAA 2006). In North Carolina, there are 97 marine managed areas including 84 state sites, 13 de facto sites, and 7 federal sites (Trappe 2004). In these marine managed areas, different levels of protection exist. For example, the Snowy Grouper MPA off the coast of North Carolina is an example of a Uniform Multiple Use MPA. The Snowy Grouper MPA prohibits commercial shark bottom longline gear, but allows trawling throughout the MPA (NOAA 2009). Although 11 different actives are allowed or disallowed, the Snowy Grouper MPA is a uniform MPA because the restrictions are the same throughout the entire MPA. State Parks, such as Carolina Beach, are more like a Zoned Multiple Use MPA because they restrict fishing and boating to limited areas (Trappe 2004). Zoned Multiple Use MPAs can also refer to areas where certain areas are prohibited at a specified time (NOAA 2006). A close example of a protection with a temporal extent in North Carolina is Black Sea Bass, which is closed February 12th through June 1st South of Cape Hatteras (NCDMF 2011). Lastly, the U.S.S. Huron MPA in North Carolina closely resembles a Zoned Multiple Use with No Take Area because it allows scuba diving, but does not allow extraction (Trappe 2004). However, the U.S.S. Huron could also be deemed Uniform Multiple Use MPA. Although the MPA is designated as no-take, the restrictions are the same throughout the wreck area. This difficulty in classifying protected areas as a particular type of MPA highlights one of the key complications in designating MPAs. Another alternative to No -take MPAs is No-access MPAs. No-access MPAs restrict all human access from an area. This is done in order to prevent all ecological impacts resulting from human use. There are few exceptions to the no access rule such as scientific research or monitoring of the area. Typically, no access MPAs are smaller MPAs that are located within larger less restrictive MPA's as is seen with the Zoned Multiple Use with No Take Area MPA. No-access MPAs in the United States are extremely rare, usually only occur as small research zones (National MPA Center 2006). No-access MPAs are particularly controversial in that they allow no human interactions such as fishing, boating, or diving. The economic impact of No-access MPAs can be greater than that of other categorizations because no human access is permitted thus limiting potential tourism and revenue from the area. In North Carolina, examples of a no access MPAs are five military areas, which do not allow anyone to enter (Trappe 2004). In addition to varying levels of protection that could be offered to North Carolina via MPAs, there already exists many regulations that protect fisheries that are not of spatial extent. For example, Red Snapper are not allowed to be possessed (NCDMF 2011). There are also various minimum length and bag limits for various marine species (NCDMF 2011). Lastly, there exist gear restrictions in North Carolina that affect pots and trawls (NCDMF 2009). In conclusion, management in the marine environment is very complex in North Carolina. There exist current marine managed areas that can be classified as various levels of MPAs along North Carolina’s Coast. In the consideration of a No-take MPA in North Carolina’s waters, the alternatives of different types of MPAs should be considered. Lastly, the current regulations that are not of spatial extent should also be evaluated when determining whether or not to impose a No-take MPA. 12 Conclusions/Recommendations Conclusions: A Marine Protected Area (MPA) is an area in the marine environment with governmental regulations restricting access and exploitation of natural and cultural resources. We consider the development of MPAs in North Carolina that would protect resources with the prohibition of exploitation but allowing human access (i.e., “no-take”). Many MPAs fail, and others are successful, but the metric for measuring success or failure is unclear and changes with the intent of each MPA. Protection of coastal habitats is currently being addressed through CHPPs and SHAs. Marine habitats protected through historical preservation (i.e. Monitor) Snowy Grouper Wreck (2009) USS Huron (Multi use w/ no take) NC currently has 97 marine managed areas. Only 5 military areas are no take along with USS Huron Archeological Preserve Requires careful planning with biology and stakeholders; adequate size and connectivity is needed for success Negative Considerations -o Expensive to start o Requires an increase in management and enforcement to be effective o Negative economic effects from lost fishing grounds and cost of enforcement o Not adequate for protecting against certain biological threats (pollution, invasive species, climate change) Positive Considerations – o Positive economic effects from spillover effect and ecotourism o CPUE increased in spillover areas o MPA time frames can vary according to purpose/flexible management alternatives (Temporal and Spatial) o Many Biological benefits including biomass, biodiversity, reproduction rate, spillover effects, and increase average size Recommendations: Conduct scientific studies to determine target fish site dependency to determine size of MPA and MPA corridors, and potential for fish fidelity Identify species and life stages for protection Use shipwreck areas for MPAs because it is dangerous for fishermen to fish there and it will help protect the shipwreck Cape Fear Banks and Cape Lookout Banks (deepwater corals) identified by NOAA should be considered as primary targets for MPA designation (Map 1) Protect Areas where trawling is high and corals are present (See Map 2) Literature Cited Allen, L. 2011. The big idea – ocean noise: Drifting in static. National Geographic 219(1):28-31. 13 American Sportfishing Association. 2009. Bush creates legacy of Marine Protected Areas. ASA Newsletter January/February 2009. http://www.asafishing.org/newsroom/news_pr_090227.html. Accessed 02/22/2011. Anonymous. No Date. Types and Categories of MPAs. Managing Marine Protected Areas: A TOOLKIT for the Western Indian Ocean. http://www.wiomsa.org/mpatoolkit/Themesheets/A1_Types_and_categories_of_MPAs.p df. Accessed 02/22/2011. Balmford, A. P. Gravestock, N. Hockley, C.J. McClean, and C.R. Roberts. 2004. The worldwide costs of marine protected areas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) 101(26):9694-9697. Bechtel, P. 2002. Building a marine sanctuary through trust. World Wildlife Fund. http://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?2631/Building-a-marine-sanctuary-through-trust. Accessed 02/26/2011. Benson , A. 2011. U.S. Geological Survey, Southeast Ecological Science Center. Nonindigenous species information bulliten Washington, DC. http://fl.biology.usgs.gov/Nonindigenous_Species/Asian_shore_crab/asian_shore_crab. Accessed 02/22/2011. Bohnsack, J.A. 1996. Marine reserves, zoning, and the future of fishery management. Fisheries 21:14-16. Brody, S. 1996. Marine protected areas in the Gulf of Maine: A survey of marine users and other interested parties. Gulf of Maine Council on the Marine Environment. http://opalwww.unh.edu/edims.html. Accessed 02/23/2011. Burgess, C. and A. Bianchi. 2004. An economic profile analysis of the commercial fishing industry of North Carolina Including Profiles for state-managed species. North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries 6:1-246. Christie, P., B.J. McCay, M.L. Miller, C. Lowe, A.T. White, R. Stoffle and D.L. Fluharty. 2003. Toward developing a complete understanding: A social science research agenda for marine protected areas. Fisheries 28(12): 22-26. Crosson, S. 2010. A social and economic survey of recreational saltwater anglers in North Carolina. North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries 1: 2-26. Crowder, L.B., S.J. Lyman, W.F. Figueira, and J.P. Priddy. 2000. Source-sink population dynamics and the problem of siting marine reserves. Bulletin of Marine Science 66:799820. Cudney-Bueno, R., M. F. Lavín, S. G. Marinone, P.T. Raimondi and W. W. Shaw. 2009. Rapid effects of marine reserves via larval dispersal. PLOS 4(1):1-7. Easley, M. F., W. G. Jr. Ross. 2005. North Carolina Coastal Habitat Protection Plan: Implementation Plan. NCDENR. http://www.ncfisheries.net/habitat/chppdocs/CombinedIP8-31-05Final.pdf. Accessed 02/23/2011. Executive Order 13158. Marine Protected Areas: Federal Register. 2000. Presidential Documents. Executive Order 13158 of May 26, 2000. 65:105. Washington, D.C. http://ceq.hss.doe.gov/nepa/regs/eos/eo13158.html. Accessed 02/22/2011. Gaylord, B., S. D. Gaines, D.A. Siegel, and M.H. Carr. 2005. Marine reserves exploit population structure and life history in potentially improving fisheries yields. Ecological Applications 15(6): 2180-2191. 14 Gell, F.R. and C.M. Roberts. 2003. Benefits beyond boundaries: the fishery effects of marine reserves. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 18(9): 448-455. Goñi, R., S. Adlerstein, D. Alvarez Berastegui, A. Forcada, O. Reñones, and G. Criquet. 2008. Spillover from six western Mediterranean marine protected areas: evidence from artisanal fisheries. Marine Ecological Progress Series 366: 159-174. Grader, Z., and G. Spain. 1999. Marine reserves: Friend or foe? What marine reserves may mean to you. The Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations. http://www.pcffa.org/fn-feb99.htm. Accessed 02/22/2011. Halpern, B. S. 2003. The impact of marine reserves: do reserves work and does reserve size matter? Ecological Applications 13(1): S117-S137. Hastings, A. and L. Botsford. 1999. Equivalence in yield from marine reserves and traditional fisheries management. Science 284: 1537-1538. Mangel, M. 2000. Trade-offs between fish habitat and fishing mortality and the role of reserves. Bulletin of Marine Science 66:663-674. MPA. 2010. About Marine Protected Areas. http://www.mpa.gov/aboutmpas/. Accessed 02/12/2011. MPA Global. 2010. World Database on Marine Protected Areas. http://www.wdpamarine.org/#/countries/about. Accessed 02/12/2011. National Marine Protected Areas Center. 2006. A Functional Classification System for Marine Protected Areas in the United States. http://www.mpa.gov/pdf/helpfulresources/factsheets/final_class_system_1206.pdf. Accessed 02/12/2011. NCDMF North Carolina Division of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Marine Fisheries. 2010. North Carolina Marine Commercial Landings. http://www.ncfisheries.net/statistics/comstat/index.html. Accessed 2/18/2011. NCDMF North Carolina Division of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Marine Fisheries. 2011. 2011 NC Recreational Coastal Waters Guide for Sports Fishermen. NC Division of Marine Fisheries. http://www.ncfisheries.net/recreational/recguide.htm. Accessed 02/23/2011. NCDMF North Carolina Division of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Marine Fisheries. 2009. Recreational Commercial Gear Licensing. http://www.ncfisheries.net/download/RCGLsummary.pdf. Accessed 02/23/2011. NOAA. 2006. A Functional Classification System for Marine Protected Areas in the United States. http://www.mpa.gov/pdf/helpfulresources/factsheets/final_class_system_1206.pdf. Accessed 02/23/2011. NOAA. 2009. NOAA Establishes Eight Marine Protected Areas to Provide Safe Havens for Deep-Water Fish. http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2009/20090113_mpas.html. Accessed 2/23/11. NOAA, Center for Coastal Fisheries and Habitat Research. 2010. Non-indigenous species information bulleton Washington, DC. http://www.ccfhr.noaa.gov/stressors/lionfish.aspx. Accessed 02/22/2011. National Marine Protected Areas Center. 2010. Glossary. NOAA. Revised March 30, 2010. http://www.mpa.gov/resources/glossary/#top. Accessed 02/23/2011. Planes, S., J. García Charton, and A. Pérez Ruzafa. 2006. Ecological effects of AtlantoMediterranean protected areas in the European Union. EMPAFISH Project 1:158. 15 Rabaut, M., S. Degraer, J. Schrijvers, S. Derous, D. Bogaert and F. Maes. 2009. Policy analysis of the "MPA-process" in temperate continental shelf areas. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 19: 596-608. Sanchirico, J. May 2000. Marine Protected Areas as Fishery Policy: A Discussion of Potential Cost and Benefits. Discussion Paper 00-23. http://www.rff.org/documents/RFF-DP-0023-REV.pdf. Accessed 02/22/2011. Stelzenmüller, V., F. Maynou, F. and P. Martín. 2009. Patterns of species and functional diversity around a coastal marine reserve: a fisheries perspective. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 19: 554-565. Suman, D., M. Shivlani, and J.W. Milon. 1999. Perceptions and attitudes regarding marine reserves: a comparison of stakeholder groups in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Ocean and Coastal Management 42:1019-1040. Trappe, C. 2004. Marine Protected Areas in North Carolina. MS Thesis, Duke University, Durham. http://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/253/Trappe%20MP%20200 4.pdf?ssequenc=1. Accessed 02/23/11. Wahle, C. M. 2003. A User’s Guide to Marine Protected Area Terms and Types: A Proposed set of Functional Descriptors. MPA Science Institute. http://www.mpa.gov/pdf/fac/wahle_definitions_final0703.pdf. Accessed 02/22/2011. Woodley S., N. Loneragan, and R. Babcock. 2010. Report on the scientific basis for and the role of marine sanctuaries in marine planning. Prepared for the Inter Departmental Committee for the Management of the States Marine Protected Areas, Perth Western Australia.