Meter Dash: Punctuation and Poetics in Leslie Scalapino`s Poetry

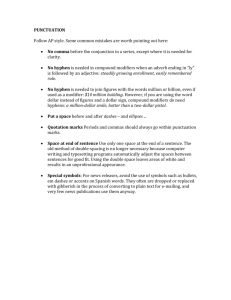

advertisement

Celia Bland/ 1 The Meter-Dash: Punctuation and Poetics in Leslie Scalapino’s Crowd and Not Evening or Light Imagine trading cards of the Major Poets (let’s call them the Major Arcana), and imagine that I have before me the Emily Dickinson card. It’s that ubiquitous nunnish headshot -- eyes like cognac, ribbon at the throat -- and in ED’s demure little hand there nestles a punctuation mark: a dash. The dash is undoubtedly Dickinson’s hagiographic symbol. Just as the Yeats card gyrates with winding gyres; and the Major Saints cards proffer a trussed and spiny Sebastian; so ED’s card features her emblematic em-dash of disambiguation. There’s another poet who might be pictured similarly, black rectangle dashing out a significant feature of eyes or mouth (as they once censored the photos of True Crime): Leslie Scalapino. Admittedly, in her early work, the late, much-lamented Scalapino used dashes as we all use them – to modify a noun (“prize-winning”) and as parenthetical phrases – like this one. But, as time went on, the dash became a far more expressive mark in her work -- that is, it became a scoring indicative of absence; a stage direction for the reader; a visual cue or clue formally repeated in patterns as intricate as in a villanelle or sestina. Certainly, Emily Dickinson used the dash to indicate her autocratic hiccups, the speeding up – and, more importantly, the slowing down – of her lines. ED insists that we pause at her interruptions in a terse percussion of modifications. Here’s an example of how punctuation modifies a poem’s meaning. When I was in grammar school I memorized a poem called “Chartless”: I never saw a moor, I never saw the sea; Yet know I know how the heather looks, Celia Bland/ 2 And what a wave must be. I never spoke with God, Nor visited in Heaven; Yet, certain am I of the spot As if a chart were given. I later discovered that in this version of the poem, published just a few years after her death, the dashes had been “smoothed away” and the vocabulary changed by ED’s editors to assert a child-like faith in the deity, a more homogeneous recognizability – oh, a poem! About faith! (This version is still quite popular in poetry anthologies for children.) This is ED’s original, untitled poem, her punctuation intact: I never saw -- a Moor — I never saw -- the Sea — Yet know I – how-- the Heather looks And what -- a Billow be I never spoke with -- God-Nor visited in Heaven— Yet certain am I of the spot As if the Checks were given— The halting steps of this version, known as #1052 in the unpublished fascicles, modify the familiar formalities of the ED’s meters, based as they were on the hymns of the Anglican Church. The child-like faith of “Chartless” gives way to skepticism and to scrutinized investigation. This handwritten original is not so much dislocated as disjointed by dashes varying in shape and even inclination (they point many directions – even vertically! -- like tiny compass needles). In so many of her poems, the pump organ Celia Bland/ 3 regularity of hymnal en- rhymes is scratched (ED as DJ “Dickmaster”) into off-beats, disruptions, reconsiderations and slant rhymes via her eccentric punctuation, as in this verse: The Brain -- is deeper than the sea— For—hold them—Blue to Blue— The one the other will absorb— As Sponges—Buckets—do— (#632) For Leslie Scalapino, the dash serves similar purposes. If we read Crowd and Not Evening or Light, a book-length poem published by Sun and Moon Press in 1992, we notice that Scalapino’s dashes are Twombly-like elements in a composition, punctuation as concrete typography. Dashes form the warp for the phrases’s woof. They are the dot dot dash telegraphing repetitive nouns: the dog, the corpse, the causing, the stowaway, the rowboat. ED’s manuscripts reveal a multiplicity of erasures, scorings and lines literally cut (with scissors!) from the paper; Scalapino’s dashes mark a similarity of impulses; the dash marks phrases excised, aborted. Then If their then that – more A play – can’t be, or As it’s being social – isn’t a version – and while – being – a born again -- though we’re not a version as the real event – from oneself – which is done again – as necessarily doing something… Celia Bland/ 4 (“The Series – 3,” from Crowd and Light, p.19) Not Evening or Where ED’s dashes roughen the figure and form both her scrutinies and her music, Scalapino’s dashes regularize the poem’s appearance, creating figure and form. A Scalapino poem becomes a series of measured phrases divided by these dashes. As we see above, the dashes begin to work the phrases, clipping expression, supplanting connective tissue with hyper-extended sinew, allowing for digression, revisions, ruminations, multiple breaths. I lived one summer in a house a block from a hospital. Some nights I would wake to the strobing hover of a helicopter delivering or collecting patients from the rooftoplanding pad. Always in the distance, sirens -- but never nearby. A city ordinance determined that, to spare the ears – and the sanity – of the hospital’s neighbors, ambulances must cut their sirens at five block’s distance. You could hear this: the echoing wail -- whoop, whoop, whooo— and then, mid-loop – silence. That’s how Scalapino uses dashes. To signify not what, but where, something has been cut or excised -- even as we anticipate that final “wh-oop!”: -- of rowers men—on the – sea—ours – as not to return to that – more inactive taking a longer time – and blue… (“as—leg”, p. 38) Celia Bland/ 5 Reading Scalapino, one might argue that punctuation seems the least important element of her work. One could discuss instead her Jamesian violence (PD James, that is -- not Henry), the loving descriptions of decomposition, the bloated corpses banging against the boathouse as waves break (think Crace’s Being Dead, or the opening of Hitchcock’s “Ten Little Indians” – that horrible yet fascinating limpness of the recently deceased). Here is the assertion and denial of both intention and form: “The following,” Scalapino writes in a note to her novel, The Return of Painting, “…is not part of the novel. (since there is not a novel.)” (63) (i.e, Having cake; eating it.) In her early books, dashes are most often merely dashes -- modifying phrases, signaling interruptions; they could have been periods or line breaks – even commas – but in Crowd and not Evening or Light, I believe Scalapino discovered this simple scoring, this black mark, as musical and conceptual tool. Sometimes her lines resemble a “notes to self,” the half-memorized lyrics of, say, “And I had put away/ my something something too/ for his civili-tee”: …how shall I be – “a mirror to this modernity” – being the reverse – then is—to—Williams’ view – or doing it is the mesh -- of being rowdy – in the jam – souped car --(“The series – as fragile—2,” p. 12) Celia Bland/ 6 Sometimes the lines hold forgetting, a partial remembering. This excerpt also reveals the difficulties of Scalapino’s line, i.e. where does the thought begin? Stanzas back? Pages back? And where does it end? Never? A poem that (minus dashes) might have resembled either an Anne Carson “essay” (or “tango”) or a Gertrude Stein “essay” (or discourse), these lines continue with a repetition of the most bland, most incommunicative words: The obtuse – situation – event --or me – other person—turmoil – as real failure (ibid, p. 13) Where does one stop? The dashes are like a patch on a bicycle wheel: flap as the wheel keeps turning, gaining speed, until it’s all flap, all dash, the percussion of puncture, flaw, absence. Like Stein, like William Carlos Williams (mentioned in the quote above), Scalapino takes America as her topic. The poems in this volume are about the impulses, the fates of the Weather Underground, Black Power, homeless people, presidents, taxi’s and perverted men – it’s like reading the newspapers, circa 1969, circa 2010. Dashes are the stanchions of these rambling run-on sentences, they are the telephones poles between the gradually slackening lines of communication, keeping prolix observations in check and readers on track. The dash becomes the joints of her sentences, exaggerated as Pinocchio’s knees and elbows. This is an efficient way to deal with difficult material. Celia Bland/ 7 The dashes tell us: this is supremely subjective; this is incapable of being completely expressed; this must be read in the perfunctory phrases of Scalapino’s breath. …--then [and perhaps you’ve noticed the repletion of then as end-line, and as prompt] if their then that – more a play – can’t be, or as it’s being social – isn’t -- a version – and while – being – a born again --though we’re not a version as the real event – from oneself – which is done again – as necessarily doing something – that would be – an event, of oneself – again – so it would be put out --negatively – though actively – and flesh – on the hoof that is the same as Rimbaud – now but in a very flaccid way – or the Weatherman -- that their events would occur – or occurred again… (“The Series –3” p. 19) I am writing this in a seaside city in the northeast that, before the advent of coal as fuel was the richest municipality in the United States. The profitability of whaling and whale oil is attested by neighborhoods of Victorian mansions far more grand than any of San Francisco’s “painted ladies.” New Bedford, Mass., is now, with the death of the Celia Bland/ 8 fishing industry, a nexus of New England’s heroin trade. Boats coming in, boats going out. Hollow-cheeked chickies nodding out on the corners of picturesque cobblestone streets. Empty fish warehouses, boats in dry-dock, cars so old their steel shells crumple like shaped foil. I would like to write about New Bedford: about the marble cenotaphs massed on the walls of Seaman’s Bethel -- launching place of the Pequod –commemorating sailors who fell from the yardarm, or were eaten by sharks, or “all hands drowned” on the Independence, the Huntress, the Christopher Twitchell, off Cape Horn, or Cape Hattaras. I would like to write about the little boy, eleven, sodomized in the stacks of the public library as patrons browsed nearby, never noticing. About the herd of deer sodomized in the local zoo. And the guard shot in the hospital parking lot by “perp or perps unknown.” About the Woman—in cart but then killed for some reason – by the men shouting spitting – rubbed with shit – (p. 37) “For some reason” – the poet’s lack of authority over real experience, over moral outcomes, over the modern age is confessed and confused. She has managed to include this inconclusive material, to witness to the meaningless. Her poems are like watching the road: car car car car car car car accident. Eventually, inevitably, predictably and yet, at random intervals, banality is punctuated by violence. She could write about New Bedford, about post-industrialized, post-most-everything America. Perplexed, Celia Bland/ 9 Scalapino’s persona is both narrator/philopher, and sometimes subject/ participant, as here when she happens upon a man (her lover?) masturbating in public: …woman—I’m – comes up to him – flesh – out – anything only, just, as movement -- while they’re standing – so they’re only moving slightly – and neither arrested – from it being movement (“Flush a Play,” p. 43) Are these interstices –dashes -- places where meaning could be posited in a rational universe? Or are the interruptions places where meaning could be but aren’t, where meaning might once have been posited in the warp and weave of American life? People are -- mules – working -- pulling -- even though very ordinary days – work violence now people dragging – or hammering pulling who’re – mules – at work in this city (“Or, A Play,” p. 46-7) Celia Bland/ 10 Notice the dash at the beginning of the line: a punctuation mark seemingly useless but symbolically indicative of elision. What is missing? Could it be faith? Belief in the order of things? For ED, the dash creates a tattoo of assertion: …The Reserve— These Heavenly Moments are— A Grant of the Divine That Certain as it Comes Withdraws -- and leaves the dazzled Soul In her unfurnished Rooms. (#393) Dickinson’s faith in “heavenly moments” is confirmed by their sudden withdrawal. Scalapino, in contrast, cannot assert the presence of anything divine except its absence —instead, we find AIDS, murders, gang rape, car accidents, Stein-ian syntax-“one” and “one” (these Everybody’s Autobiography-suffused pronouns) -, homeless people freezing on the street, men’s stems (an odd euphemism, repeated in The Return of Painting) and poems signed with Scalapino’s name, the date and the temperature: “102 degrees F.” And no connection to those things, or between these things. Instead, all the things I wish I could put in my work: this moment’s fractyl snap of sprinklers, snap, snap, emphatic snap of hedge trimmers, snap of car doors shutting, the snap of dishwasher door shutting, the bass snap of ice releasing from frigid trays, the snap of knee sitting at the breakfast table, -- and no striving after snap meaning – except, perhaps, Scalapino’s telephone wires of extended discourse, questioning our urge to activity, to progress, to act in violent and loving ways, and the meaning of all the things we experience. I see Crowd and Not Evening or Light as the apotheosis of Scalapino’s work and also as the most complete description of her/our moral quandary, the striving to imbue Celia Bland/ 11 language with a meaning no longer inherent in its corpus. Perhaps in, say, the Elizabethan age, or even in Dickinson’s age of civil wars and slavery, a word, manyfaceted, phonetically spelled, describing the Orient, the East, the mythology of cannibalism, the rigging of a ship, referred to something -- in this world, in the world of ash or shade or regret – that was experientially real. Facts be damned. Words in Dickinson are blocks of wood carefully placed, typeset letters in little Cornell boxes, infinitely recombined and always felt. Or maybe I say this from longing as I prepare a Power Point presentation, clicking on backgrounds fonts bulleted points shadings clipart slides. Do these words mean anything? They strike me as so much pap, so much masticated chaw deposited in a pelican's maw. Spit, spit. I haven’t mentioned one of the most interesting aspects of this volume, a long section of snapshots underwritten with Scalapino’s cursive captions. The photographs may remind viewers of Robert Frank’s Mabou series, which features mundane views, sometimes unfocussed, sometimes scratched and scored, collaged together in ways that suggest distress, stress, and electricity. Scalapino apparently set the camera on a tripod and snapped at random, without looking through the viewer. The photos – men in waves, and swinging on rings, surfers, skaters, palm trees and sidewalks -- are captioned with repetitious and yet euphemistic phrases: men sitting on their hams, men fingering their stems, “the nudity of poverty and calm.” (87) Franks’ Mabou photos are notable for a perspective seemingly indiscriminate. Even as the mind receives the images, they are disrupted (as Scalapino’s lines are by dashes) as poorly assembled collages. These collages repeat images of telephone poles, for instance, extending the image again and Celia Bland/ 12 again, creating ugly additions, randomized agglomerations of poles, of meaning and notmeaning. Scalapino’s efforts strike me as much less interesting. I admit that I agree with poet and critic Elizabeth Frost’s impassioned explication of these photos, and this book as a whole: “Scalapino…mixes signifying systems and modes of representation to get at a new conception of bodies… [she] also evokes a tradition that articulates social critique in and through an empirical body, an eroticized and a social body, through which ‘the personal is political’ and ‘body politics’ matters.” (“How Bodies Act: Leslie Scalapino’s Still Performance,” How2, vol. 2, issue 2, Spring 2004). This may be so, but perhaps, for Scalapino, whose later books of poetry focused on politics and social injustice, the dash – here at its most powerful -- quickly loses its utility, becoming an eccentric tic, replaceable by images – or the carapace of words as images. The powerful interruption that sustained ED, irregularizing her heartbeat’s meter, cannot be maintained for even one of Scalapino’s volumes. I am reminded of Brazilian poet Augusto de Campos’s 1950’s manifesto for concrete poetry. He wrote that it “accept[s] the premise of the historical idiom as the indispensable nucleus of communication, it refuses to absorb words as mere indifferent vehicles, without life, without personality without history - taboo-tombs in which convention insists on burying the idea…” (“Concrete Poetry” in Contemporary Poetics, Louis Armand, ed., Northwestern Univ. Press, 2007.) In these captions, Scalapino’s words seem “indifferent vehicles”: Backing up the bully in the Very nature – living it Scratch Celia Bland/ 13 On it (they) like reality as a function scratch on it scratch on it scratch on it (“Crowd and Not Evening or Light,” pgs. 90-91) It’s inspiring – in the negative.