“Diagnosing” Globalization`s Environmental Health

advertisement

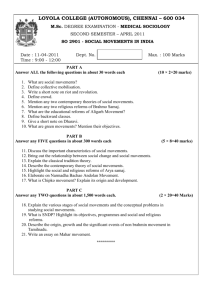

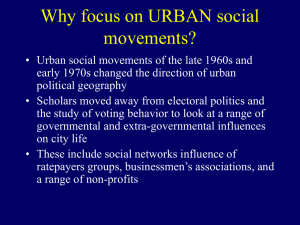

“Diagnosing” Globalization’s Environmental Health Consequences: Local and Global Health Social Movement Struggles Stephen Zavestoski Departments of Sociology and Environmental Studies, University of San Francisco, 2130 Fulton St., San Francisco, CA 94117-1080; email: smzavestoski@usfca.edu Abstract The labor, environmental, economic, and health consequences of globalization have been well documented. Less clear are the ways in which the same forces of globalization that expose more and more people around the world to environmental health risks are also creating new networks of environmental health activists that link local health social movement struggles to a global network of environmental health activism. This paper will document some of these linkages and explain how the emerging network of global environmental health activists assists local efforts to identify pollutionrelated disease, diagnose it, and mobilize for policies that more effectively safeguard human health. The paper concludes with a discussion of the network of global environmental health activists that focuses on the following question: How can local activists ensure that their personal experiences of disease and local knowledge of environmental hazards is not overshadowed by the abstract legal and scientific knowledge that often defines the professionalized global movement organizations? Social movements oriented around health issues have a long history. Only recently, however, have social scientists begun seriously examining health social movements, in the process producing some useful theoretical developments and valuable empirical case studies. The case studies, and the theories that have been built around them, depend largely on examples of health social movements in the United States, Canada, and Europe. Less is known about how, or whether, similar health social movements have emerged in other parts of the world. What we now understand about health social movements—their tendency to challenge or contest medical and scientific knowledge and practice, their focus on the physical body as a place of contestation, and their unique alliances with sympathetic scientists and health professionals—raises interesting questions with respect to the potential for health social movements in less developed parts of the world. I look to India as an ideal place to begin exploring health social movements outside of the western economic powers of the United States, Canada, and Europe.1 In India, as in other less developed parts of the world, the presence of international nongovernmental organizations is strong. Consequently, to adequately understand health social movement organizing in developing parts of the world, health social movements need to be situated in the larger social process known as globalization. The increasing global exchange of information, knowledge, and capital seems to be producing two contradictory forces: an increase in the amount and types of industrial contamination to which citizens of less developed countries are exposed; and an increase in the amount of access victims of this contamination have to the medical, scientific, and public health resources needed to contest contamination-related illnesses. These countervailing forces provoke the question that is at the heart of this paper: How does illness contestation play out when local activists, whose personal experiences of disease and local knowledge of environmental hazards informs their activism, utilize the medical, scientific, and legal resources provided to them by professionalized global movement organizations? After a discussion of recent research on health social movements, I will focus on the subset of HSMs referred to by Brown et al. (2004) as embodied health movements. I will also elaborate on some key conceptual terms for examining embodied health movements. In the next section I bring these concepts to bear on two past and present environmental health controversies in India with the aim of illuminating some of the key questions future research needs to answer. I conclude by providing several examples of environmental health controversies in other parts of the less-developed world in order to illustrate that the questions raised by the Indian examples are not unique. Background on Health Social Movement Research Health social movements have been defined as “collective challenges to medical policy, public health policy and politics, belief systems, [and] research and practice” (Brown and Zavestoski, 2005). Brown et al. (2004) point out a wide range of successful movements fitting this definition: efforts to improve occupational health date back to the Industrial Revolution, mental health patients and those with physical disabilities have been successful at achieving expanded rights; the broader women’s movement has won many victories for women’s reproductive health rights and more recently succeeded in altering medical research practices (Morgen, 2002); AIDS activists have successfully mobilized to achieve disease recognition, research funding, and treatment advances (Epstein, 1996); toxic waste activists also represent an example of successful health social movement mobilizing, helping develop national and international regulations and bans on toxic substances. But there is a curious anomaly with respect to health social movements noted by Brown and Zavestoski (2004). Despite their social and historical significance, health social movements have been studied mainly by medical sociologists, historians, or others without paying specific attention to advances in social movement theory and research. Sociologists and others who study social movements have paid little attention to health social movements. Recently, however, there has been a significant interest in the study of health social movements. Evidence of this emerging interest can be found in presentations at professional meetings (e.g., special sessions on health social movements at recent meetings of the Society for Social Studies of Science), journal special issues (e.g., the December 2004 issue of Science as Culture on “Health, the Environment, and Social Movements,” the Novemember 2002 issue of Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science on “Health and Environment”), and in a new monograph by Brown and Zavestoski titled Social Movements in Health (2005), which was originally published as a special issue of Sociology of Health & Illness. In reviewing the landscape of health social movement research, Brown and Zavestoski identify three categories of health social movements: (1) “health access movements” (i.e., movements focused on access to, and provision of, health care); (2) “constituency-based health movements” (i.e. movements focused on the structural factors that cause health inequality and inequity based on race, ethnicity, gender, class and/or sexuality); and (3) “embodied health movements” (i.e., movements organized around specific illnesses, diseases, or disabilities). It is the third category of health social movements, which Brown and Zavestoski claim often involve contestations over disease identification, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention, that is central to an analysis of environmental health activism in developing parts of the world. Pollution-related illnesses result not just in contestations with the medical profession, but also with government, science, the law, and the private sector (e.g., corporations). The increasing frequency with which we witness embodied health movements forming to contest the definition, diagnosis, or treatment associated with a disease, according to Brown and Zavestoski, is a function of several factors: “growing public awareness about the limits of medical science to solve persistent health problems that are socially and economically mediated, the rise of bioethical issues and dilemmas of scientific knowledge production, and ultimately the collective drive to enhance democratic participation in social policy and regulation.” Furthermore, as evidence for the need for a better understanding of embodied health movements, Brown et al. (2004) point to two simultaneous trends—the empowerment of patients toward more active involvement in their healthcare and growing numbers of unexplained illnesses with purported environmental causes. These trends are not as pronounced, or may not even exist, in the developing world. The numbers of unexplained illnesses with suspected environmental causes may be increasing, and there may even be strong evidence of movements to enhance democratic participation, but the empowerment of patients seems more of a developed world phenomenon. Concerns about the limits of medical science or the overscientization of health, two of the forces behind patient empowerment, are irrelevant in less-developed parts of the world that often lack basic health care. These differences with the embodied health movements studied by scholars in the developed world make the study of embodied health movements in the developing world even more vital. Where citizens depend on indigenous health care, where they lack access to western diagnostic practices, or where they lack scientific resources to link their symptoms to environmental causes, embodied health movements, where they form at all, are likely to follow a very different course than embodied health movements in the developed world. I hypothesize that the formation of embodied health movements often depends on the presence of national-level or transnational social movement organizations that perceive a disease/pollution link and see an opportunity to mobilize against the state, corporations, or international forms of governance like the World Bank, WTO, GATT, or IMF. The disease of individuals, and contestations over their cause, becomes a battlefield for transnational social movement organizations to challenge the poverty, inequality, injustice, and environmental degradation resulting from the processes of globalization. I am interested in the way that individual illness experience, situated in local social and cultural contexts, gets transformed into contestations over the global social order. In the next section I will discuss some theoretical concepts that have been employed in the study of embodied health movements. I will try to illustrate their relevance to understanding the relationship between individual illness experience and transnational social movement organizing against the forces of globalization before applying them to several cases of pollution-based health activism in India. Embodied Health Movements: Theoretical Conceptualizations Brown et al. (2004) define EHMs in terms of three characteristics: the centrality of the biological body to movement formation and strategy; the importance of challenging existing medical/scientific knowledge and practice; and the collaboration between activists and scientists or health professionals in order to produce knowledge about disease detection, treatment, and prevention. Brown et al. also note that while the simultaneous possession of these three characteristics makes embodied health movements somewhat unique, they are nevertheless similar to other movements in that their emergence depends on the shaping of a collective identity. For embodied health movements, Brown et al. argue, the collective identity tends to result from the politicization of one’s illness experience. Most people manage illness privately, or seek advice or care from family or close friends. As long as these strategies relieve symptoms and/or suffering, the illness experience never becomes politicized. But when these strategies fail, individuals often venture into the world of institutionalized medical care where scientific and medical knowledge can be brought to bear on their conditions. If the institutions of science and medicine fail them, individuals may become quite frustrated or despondent. It is at this point, when authoritative social institutions like science, medicine and government offer accounts of disease that are inconsistent with individuals’ own experiences of illness, that people may adopt an identity as an aggrieved illness sufferer. At this stage, individuals may become aware that they share this new illness identity with others. If so, they begin to move toward what Brown et al. 2004) call a politicized collective illness identity. Politicized Collective Illness Identity Social movements scholars have amassed a strong body of evidence illustrating the significance of collective identity in social movement mobilization (Poletta & Jasper, 2001). Brown et al. borrow the concept of collective identity and combine it with the concept of illness identity from the sociology of health and illness to arrive at the concept of a “politicized collective illness identity.” Poletta and Jasper define collective identity as “an individual’s cognitive, moral, and emotional connection with a broader community. It is a perception of a shared status or relation, which may be imagined rather than experienced directly, and it is distinct from personal identities, although it may form part of a personal identity” (2001, p. 285). Illness identity, on the other hand, is the individual sense of oneself shaped by the physical constraints of illness and by others’ social reactions to that illness (Charmaz, 1991). When individuals, through the illness identity acquired as a result of their illness condition, develop a “cognitive, moral, and emotional connection” with other illness sufferers, a collective illness identity emerges. Adding the word “politicized” to “collective illness identity” helps distinguish it from the types of collective illness identities seen in illness support groups. Individuals with a politicized collective illness identity differ from those without in that they are concerned with the role of power and politics in shaping the forces that led to the disease in the first place. An unpoliticized collective illness identity may be important in connecting people with shared illness experiences in order to relay knowledge about treatments or symptom alleviation, but it is unconcerned with the causes of the illness (or, sees the causes as unproblematic when making sense of the disease). How do collective illness identities form? One possibility is that they emerge as a person seeks care for a condition by moving through a variety of social institutions. The foremost among these institutions are the health care system writ large, including medical practice, medical science, and health insurance. For example, people with an undiagnosed condition (whether the condition has suspected environmental causes or not) must deal with the shattered expectations that the medical profession has an explanation and cure. Then they must deal with family members or others who may begin doubting whether they are really sick. Employers and insurers are unlikely to fulfill their obligations to provide sick leave or financial compensation to people with an undiagnosed condition. As frustration builds as a result of facing persistent obstacles in a range of institutions, individuals may come into contact with others with similar experiences. Brown et al. (2001) argue that these shared experiences emerge through people’s experiences within a “dominant epidemiological paradigm,” the formal or quasi-official set of beliefs that social institutions, and the actors within them, have about disease and its causation. But even if people become frustrated as these institutions fail them, how do they find one another to form a collective illness identity? For unique or rare conditions, doctors’ offices often serve a networking function by connecting patients with one another or with patients in other practices. Once a condition becomes more common, or people with that condition become more aware of one another, formal organizations tend to emerge. Programs offered by these organizations—whether widely known, like the Muscular Dystrophy Association, or little known like the Alkaptonuria Society—help create a collective illness identity. When a person fails to find sufficient support within the formal channels of medical practice, she or he may begin seeking information and help elsewhere. The Internet, for example, has become an important networking tool in the creation of support groups and other formal and informal illness organizations (Broom, 2005; Gillett, 2003; Shriver et al., 2003; Ziebland, 2004). One study goes so far as to suggest that the Internet helps in the construction of illness itself, not just the collective illness identity (Weisgerber, 2004), while another study concludes that Chronic Fatigue Syndrome sufferers successfully use the Internet to “keep the disease going” in the face of widespread disbelief of its biological origins within the medical community (Loriol, 2003). In some cases, the Internet may also be used as a tool to politicize a collective illness identity. AIDS activists represent the most prominent example of using the Internet to politicize a collective illness identity (Epstein, 1996; Gillett, 2003). The Internet, and other media sources, are also important in terms of exposing people to information about environmental disease. In the media-rich United States, for example, Americans do not even need to watch the news to know about individuals or communities that have fought to establish connections between disease and pollution. Blockbuster films and books like “Erin Brockovich” and A Civil Action have made most Americans aware of such battles. Exposure to such stories provides a cognitive schema for making sense of unexplained illness, and has led some to talk about “postmodern illnesses” (Morris, 1998) arising out of the intersection of biology and a form of latecapitalist consumer culture in which popular media messages construct reality (Zavestoski, et al. 2004). Similarly, Wessely (2001) argues that perceived environmental hazards and threats shape popular models for illness and disease in ways they previously did not. In other words, collective illness identities are now more likely to become politicized, at least to the extent that people embrace the idea that corporations, the industrial economy, and/or the government are to blame for disease-causing environmental pollution. Politicization of a collective identity entails the construction of a broader social critique that views structural inequalities and the uneven distribution of social power as responsible for the causes or triggers of the disease (Zavestoski et al., 2004). Politicization also removes responsibility for preventing the disease—for example, preventing human contact with disease-causing toxic substances—from the individual and places it on social institutions. In the language of Mills’ sociological imagination, “a politicized collective illness identity begins the process of transforming a personal trouble into a social problem” (Zavestoski et al., 2004, p. 269). Once politicized, a collective illness identity shifts individuals’ attention away from treatment and instead focuses attention on structural explanations of disease and the requisite structural changes to prevent the disease. In the developing world, embodied health movements presumably emerge under very different conditions due to a lack of the triggering factors discussed above. First, individuals are likely to have far less, if any, exposure to media coverage of other diseases linked to environmental hazards. The media influences and postmodern social construction of disease hypothesized by Morris (1996) and Wessely (2001) simply are not present in the developing world. Knowledge that modern industrial processes increasingly expose humans to toxic substances must be present before a person thinks to link her or his condition to environmental causes. Even if people suspect their illnesses have environmental explanations, without access to the institutions that make up the dominant epidemiological paradigm the frustration that opens them up to a politicized collective illness identity may not occur. Without health care, individuals suspecting environmental causes of their condition never interact with skeptical medical professionals. Instead, people will continue to seek care through traditional healing practices or other avenues. Take Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, for instance. Because the medical profession is largely skeptical of MCS’ biological origins, as Brown et al. write, “individuals who believe they have MCS become frustrated with the medical system, find themselves in court challenging insurance companies who deny them coverage, and develop personal strategies for minimizing reactions and managing symptoms (Kroll-Smith and Floyd 1997)” (Brown et al., 2004, p. 61). MCS sufferers politicized their collective illness identity in order to mobilize the previously unorganized MCS community toward the end of challenging medical professionals skeptical of their condition. According to Brown et al., “When disease groups experience their conditions in ways that contradict scientific and medical explanations, and these contradictions are identified as a source of inequality, a politicized collective illness identity may emerge” (2004, p. 61). Lacking contact with the institutions of western medicine and science, most individuals in developing parts of the world lack what has been identified as a key factor in the formation of a politicized collective illness identity among the embodied health movements that Brown et al. (2004) have examined in the U.S. What, then, is the mechanism for the formation of embodied health movements in developing parts of the world? Transnational Social Movement Organizing In the brief case studies I examine below, I will try to illustrate how transnational social movement organizations were instrumental in forming and politicizing collective illness identities. To do that, I need to discuss the emerging body of literature on transnational social movements. In short, some scholars of social movements have begun focusing on the ways in which some of the same factors facilitating the spread of global capital alter the landscape over which social movements mobilize for social change (Guidry et al., 2000; Keck & Sikkink, 1998; Smith et al., 1997; Smith & Johnston, 2002). These scholars have tended to begin by asking how the weakened position of the state under the pressure of economic globalization forces agents of social change to find new targets of their opposition. The result is that much scholarship focuses on the role of large and often well-resourced transnational social movement organizations in negotiating international agreements. Much of this scholarship has come from the “contentious politics” (Tarrow, 1998) tradition of social movements theorizing. From this perspective, the most relevant movements to study are those that directly challenge the state or other authority structures (also see McAdam et al., 2001). Revolutionary movements and rights-based movements (e.g., human, civil, or women’s rights movements) receive great attention. Movements that emerge in response to health consequences resulting from environmental pollution are less likely to receive attention. Yet these movements are prominent, and increasingly they ally with larger regional or international organizations that have more resources and better access to political opportunity structures. In most cases, transnational movement organizations help local communities and disease sufferers in ways they cannot help themselves. Nevertheless, there are important aspects of this approach to the mobilization of environmental health activists that beg for exploration. An international organization, for example, might fail to understand the influence of the local political, cultural, and historical context on individuals’ failure to link disease or illness with pollution. Or, where local residents have mobilized, international organizations may not comprehend the various factors constraining or enabling the movement. International organizations may see local incidents of pollutionrelated disease as an opportunity to raise larger issues about globalization and its consequences for less developed countries. No research addresses whether these are real outcomes of local grassroots efforts joining regional, trans-regional or global activist networks, which is why I use the examples below to suggest research directions that might answer the following question: How does illness contestation play out when local activists, whose personal experiences of disease and local knowledge of environmental hazards informs their activism, utilize the medical, scientific, and legal resources provided to them by professionalized global movement organizations? Ongoing Illness Contestation in Bhopal The best example of the complicated relationship between local disease sufferers and national and transnational movements is the 1984 industrial disaster in Bhopal, India. On the evening of December 2, a number of systems in Union Carbide’s plant simultaneously failed and methyl icocyanate (MIC) was released into the atmosphere. Emergency alarms failed to signal the disaster and most residents ran for their lives. The fortunate ones ran against the wind, others who ran with the wind could not escape the chemical cloud. The Government of India has settled on an official death toll of about 3,000. More aggressive estimates place the total at 15,000. The inability to get treatment, both in the immediate aftermath and in the ensuing 20 years, has undoubtedly hastened the deaths of many more. Scholars and activists alike have written extensively about what caused this technological crisis1, yet none have examined systematically the rapid, extensive, and contentious social movement mobilization that occurred immediately after the disaster and that continues to this day. Due to a variety of obstacles put in their way, victims of the Bhopal disaster have had to engage in constant contestations with medical and legal experts, and with government officials (Das, 2000; Fortun, 2001; Rajan, 2002). In a review of the medical literature on the effects of MIC exposure, Mehta et al. (1990) report acute effects including respiratory problems, eye irritation, and circulatory, gastrointestinal, and central nervous system complications. Long-term effects identified include impaired pulmonary function and restrictive lung disease. Additionally, Mehta et al. (1990) report that pregnant women exposed to the gas miscarried at a rate of 43 1 I prefer the word “crisis” to “disaster” for the same reasons as Shrivastava (1987, 1994). Namely, crisis denotes an ongoing disruption of social order to which various social actors respond, whereas disaster focuses attention on a single event and its impact upon social actors. percent. The authors add that inadequate data exist to report on the impacts on children, the immune system, neuromuscular system, blood and metabolism, and psychological health. The challenges victims have faced result, in part, from a lack of systematic epidemiological study. Koplan et al. (1990) argue that the study of disaster-related health effects poses great challenges in and of itself. They conclude that “better mortality estimates in Bhopal could have been made if a team of interviewers had been sent out immediately afterwards to gather data” (Koplan et al., 1990, p. 2796). With respect to an event like the Bhopal disaster, scholars have focused on the root causes of the disaster (Bogard, 1999; Shrivastava, 1994), lessons learned in corporate risk management (Piasecki, 1994; Sen & Egelhoff, 1991), and more comprehensively the causes and consequences of the crisis (Shrivastava, 1987). None of these analyses have focused systematically on the failure of civil society organizations to launch and sustain a coordinated and efficacious response. Yet many lessons can be learned from the Bhopal gas leak and its aftermath—a crisis that spawned numerous social movement organizations, attracted many others from near and far, and brought them together in a political, economic, legal, and cultural context that prevented any of them from achieving their goals of securing adequate relief and rehabilitation for survivors. In the case of the Bhopal disaster, those affected immediately linked their symptoms to the gas leak. Unlike other disease-related movements that come to suspect a particular exposure over time, exposure to MIC in Bhopal was the obvious culprit.2 2 One difficulty faced by those exposed was the slowness with which Union Carbide and the Government of India released information about what was released in the explosion on the night of December 2. As a result, medical care providers were unsure what course of treatment to pursue . Victims did not become immediately mobilized, but activists from throughout India and across the world did. Over time, a combination of Bhopal-specific organizations (e.g., the Bhopal Gas Affected Women Stationery Employees Union, Sambhavna Trust), larger national organizations (e.g., the Morcha), and professional international organizations (e.g., the International Coalition for Justice in Bhopal, Greenpeace) formed a loose-knit movement. Conflcits among the various movement organizations emerged almost immediately, severely hampering the formation of a politicized collective illness identity. Sarangi, for example, writes that the Zahreeli Gas Kand Sangharsh Morcha (known as the Morcha) and Nagarik Rahat Aur Punarvas Committee (NRPC), which formed within the first week after the disaster, had immediate disagreements: “The NRPC viewed Morcha as doing politics instead of providing help, and the Morcha thought of NRPC as a bunch of reformists with dubious motives” (Sarangi, 1996, p. 100). Later, trade union activists from Bombay came to Bhopal seeking to reopen the Union Carbide plant in another manifestation in order to restore lost jobs. Meanwhile, the Morcha patently refused to accept support from organizations in the U.S. or elsewhere outside of India. Further study of the Morcha, NRPC, and the many other organizations that followed them, and why they failed to work together more effectively, would go along way toward understanding the emergence of a formal Bhopal movement and a politicized collective illness identity within it. Such research could aim to develop a typology of the organizations that emerged from, or came to address, the crisis in Bhopal. Historical analysis of the various organizations that have come and gone might also tell us why certain groups emerged when they did and failed when they did. My suspicion is that the challenges created by corporate and government incalcitrance caused the organizations to work against, rather than with, each other. It is also possible that too many movement organizations led by individuals who were not immediately affected by the disaster resulted in movement priorities that were out of touch with the primary interests of victims. I believe Bhopal has another lesson to teach us about embodied health movements in developing parts of the world. This lesson has to do with the way contesting illness with transnational corporations—whose culture, politics, acceptable levels of scientific proof, and morals differ from the affected group’s—requires a creative blurring of local and global on a number of levels. Sambhavna Trust, a community clinic in Bhopal and one of the longest existing movement organizations, has demonstrated that a combination of traditional Ayurvedic medicine, yoga, and some western medicine, offers the best results in the treatment of respiratory and other common MIC-related symptoms. The current campaigns by International Coalition for Justice in Bhopal and Greenpeace, who have begun working with the long-running Bhopal Gas Affected Women Stationery Employees Union, also reflect a blurring of the local and global. Finally, on the legal front, activists are pursuing a case against Dow Chemical, which purchased Union Carbide in 2001, as a way of working around legal obstacles within India. Coca Cola in Kerala In 1999, Hindustan Coca-Cola Beverages Pvt. Ltd, a partially Indian-owned subsidiary of the U.S.-based multinational company, began manufacturing soft drinks in Plachimada, a tiny rural village in the Southern Indian state of Kerala. Within two years of the plant opening, villagers living nearby began reporting stomachaches that they believed to be related to contamination of their groundwater by the plant. Many began walking to a nearby well unaffected by the plant’s operations. In addition, farmers reported decreased yields due to reductions in the amount of water available to them.3 It has also been reported that the company is pumping wastewater into dry bore wells to dispose of solid waste. As a report by India’s Research Foundation for Science, Technology & Ecology explains, “earlier it was depositing the waste material outside the company premises which during the rainy season spread into paddy fields, canals and wells, causing serious health hazards” (undated, p. 3). Water tests characterized the water as having high levels of salinity and hardness, due to concentrations of calcium and magnesium likely resulting from drawdown of the water table. Due to these factors, the water coming from the wells in a 1.5 km radius around the plant is “unfit for human consumption, domestic use (bathing and washing), and for irrigation” (Bijoy, 2004). The struggle began on April 22, 2002, when villagers began picketing the plant. Their demands included: (1) that the plant be shut down because it was devastating the ground and surface water; (2) that the Coca-Cola company be held fully responsible and liable for the destruction of livelihood resources of the people and the environment; and (3) that criminal action be taken against the company. The leaders of the picket formed what came to be known as the Coca-Cola Virudha Janakeeya Samara Samithy, or the “Anti Coca Cola People’s Struggle Committee.” 3 For background on this case I am drawing from a Master’s thesis by Eva Wramner (2004) of Lund University, Sweden, and a number of the websites created by the various NGOs who become involved with the struggle. These resources are listed at the end of the article “Adivasis Launch Struggle Against Coca Cola,” by C. R. Bijoy http://ghadar.insaf.net/June2004/MainPages/coke.htm (accessed August 31, 2005). This case is particularly interesting for two reasons: (1) the affected population is largely made up of Adivasis, the Government of India’s term for “primitive tribes;” and (2) as opposed to being strictly about pollution-related disease, the grievance has to do with a combination of health and livelihood concerns (caused by the inability to farm or carry on daily chores requiring sufficiently clean water). The first characteristic points to the need to build on the understanding of North-South differences in environmental activism (Guha & Martinez-Alier, 1997) in order to extend it to environmental health activism. Smitu Kothari (1996), for example, notes that movements involving indigenous people differ from developed world movements in that there is no common ideology or attempt to shape a political agenda. Demands usually have to do with getting basic survival needs met. Yet the Adivasis struggling against Coca Cola in Plachimada represent an embodied health movement, which leads us to the second interesting characteristic of this movement—its combination of health and livelihood concerns. Rather than being embodied in the sense of experiencing a particular disease, the movement is embodied in a different way: trekking longer distances for clean water, or the lack of sufficient amounts of water, has direct impacts on the body. Furthermore, as larger Indian NGOs—like the India Resource Center, the People’s Union for Civil Liberties, and the National Alliance of Peoples Movements—and even international NGOs (e.g., the World Social Forum, the International Campaign Against Coca Cola) became involved, new questions about the importance of embodiment in driving environmental health movements are raised. These organizations may see the movement as more about multinational corporations exploiting the defenseless and less about the immediate health and livelihood needs of the Adivasis. In other words, embodiment may become a less central component of the movement, which likely results in a fundamentally different movement in terms of goals set, strategies employed, and other dimensions of movement mobilization. Further research should aim to answer questions such as: To what extent do national and international organizations advance the goals of indigenous environmental health movements? In what ways do these organizations introduce new goals to the movement? Are indigenous voices and local experiences heard through the din of movement strategizing and campaigning by large professional organizations? Examples from Other Parts of the World In order to determine whether the questions I have identified from the Bhopal and Plachimada struggles reflect relevant concerns about illness contestation in developing parts of the world, additional cases should be examined. For example, activists in Vietnam have begun working on a lawsuit against Dow Chemical Corporation, the manufacturer of Agent Orange, since the U.S. government has closed the books on its responsibility to victims of Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam. Historically, however, much of the Agent Orange activism in Vietnam has been headed by U.S. military veterans who have returned to Vietnam and vowed to assume a certain amount of personal responsibility by advocating for Agent Orange victims. Another case that warrants more careful examination is the ongoing lawsuit in Indonesia against Newmont Mining Corporate. The Public Prosecutor’s Office in Indonesia brought a suit naming not just the corporation, but two individuals within the corporation, as legally liable for extensive contamination of Buyat Bay. The Indonesian Forum for the Environment (WALHI) has been actively campaigning against the mining multinational for years and working to amass scientific evidence of the presence of mining-related contamination and the related human health impacts. Newmont contends that there is scientific evidence to the contrary. As this lawsuit plays out, we will have an opportunity to learn much about the role of indigenous people’s personal lived experiences as a basis for evidence in a developing country’s legal system. Conclusion I have attempted to provide an overview of the emerging research on health social movements, and embodied health movements more specifically. I described some of the theoretical and conceptual tools introduced in recent health social movement research, and explained how they might be adapted to investigate embodied health movements in developing parts of the world. In conclusion, I want to point out some of the developments in the world of transnational social movement organizing as they may prove significant in the future of environmental health activism in the developing world. Information technologies, among a variety of other contributions of globalization, have made it possible for activists around the world to network in ways previously unavailable. The best example of this is the connections made between Bhopal activists and Vietnamese Agent Orange activists during the 2004 World Social Forum in Mumbai.4 At the same event—organized with the explicit intent of networking all social justice movements around the world—activists from Plachimada hosted a workshop with activists from Columbia, who are similarly engaged in a fight against Coca Cola. 4 Union Carbide, the American company that owned, with its Indian subsidiary, the plat in Bhopal that leaked MIC in 1984, was bought by Dow in 2001. Hence activists in Bhopal now share a common enemy with activists in Vietnam. Future research, therefore, should aim to address a range of larger questions that extend beyond environmental health activism. Have the forces of globalization made local activists more brazen, so that poor Dalit’s in Bhopal or landless Adivasis in Plachimada believe they can take on corporate giants like Dow or Coca Cola? Do grassroots efforts in Colombia benefit by collaborating with similar grassroots efforts halfway around the world in India? Are there parallels between globalization’s blurring and erasing of geopolitical and economic boundaries and the boundaries that are being blurred between local and transnational social movements? What is the significance of the blurring of the boundary between the labor, environment, health, human rights, women’s, and other social justice movements? Are the networks that are being created new, or have we seen them before in other movements? And what impact do they have, in particular on the efforts of local people to engage in illness contestations? Finally, to bring us back to some of the concepts introduced earlier, what are the roles of politicized collective illness identities in these movements? How has the type of global networking described above changed the way in which politicized collective illness identities form? Answering these questions will require some wide-ranging research, but the answers may be vital to embodied health movements and environmental health activists far into the future. Acknowledgements I have Phil Brown, and the entire Contested Illness Research Group at Brown University, to thank for the stimulating discussions and challenging research in which we have engaged over the last few years. Out of these exchanges emerged the ideas on health social movements presented in this paper. References Bogard, William. (1989). The Bhopal Tragedy: Language, Logic, and Politics in the Production of a Hazard. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Broom, Alex. (2005). The eMale: Prostate cancer, masculinity and online support as a challenge to medical expertise. Journal of Sociology 41(1), 87-104. Brown, Phil, & Zavestoski, Stephen. (2004). Social movements in health: An introduction. Sociology of Health & Illness 26, 679-694. _____. 2005. Social Movements in Health. New York: Blackwell. Brown, Phil, Zavestoski, Stephen, McCormick, Sabrina, Mayer, Brian, Morello-Frosch, Rachel, & Gasior Altman, Rebecca.( 2004). Embodied health movements: New approaches to social movements in health. Sociology of Health and Illness 26, 5080. Charmaz, Kathy. (1991). Good Days, Bad Days: The Self in Chronic Illness and Time. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. Das, Veena. (2000). Suffering, legitimacy, and healing: The Bhopal case, critical events. In, Steve Kroll-Smith, Phil Brown, and Valerie J. Gunter (Eds.), Illness and the Environment: A Reader in Contested Medicine. New York: NYU Press. Epstein, Steven. (1996). Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press. Fortun, Kim. (2001). Advocacy After Bhopal: Environmentalism, Disaster, New Global Orders. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Gillett, James. (2003). Media activism and Internet use by people with HIV/AIDS. Sociology of Health and Illness 25(6), 608-624. Guha, Ramachandra, & Juan Martinez-Alier. (1997). Varieties of Environmentalism: Essays North and South. London: Earthscan. Guidry, John A., Kennedy, Michael D., & Zald, Mayer N. (Eds.) (2000). Globalizations and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Keck, Margaret E., & Sikkink, Kathryn. (1998). Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Kothari, Smitu. (1996). Social movements, ecology and justice. In, Fen Osler Hampson & Judith Reppy (Eds.), Earthly Goods: Environmental Change and Social Justice(pp. 154-172). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Koplan, Jeffrey P., Falk, Henry, & Green, Gareth. (1990). Public health lessons from the Bhopal chemical disaster. Journal of the American Medical Association 264(21), 2795-2796. Kroll-Smith, Steve, & Floyd, Hugh H. (1997). Bodies in Protest: Environmental Illness and the Struggle over Medical Knowledge. New York: New York University Press. Loriol, Marc. (2003). The need to keep a controversial disease going: The associations of patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and the Internet (Faire exister une maladie controversee: les associations de malades du syndrome de fatigue chronique et Internet). Sciences Sociales et Sante 21(4), 5-33. McAdam, Doug, Tarrow, Sidney, & Tilly, Charles. (2001). Dynamics of Contention. New York: Cambridge University Press. McCormick, Sabrina, Brown, Phil, & Zavestoski, Stephen. (2003). The personal is scientific, the scientific is political: The public paradigm of the environmental breast cancer movement. Sociological Forum 18, 545-576. Mehta, Pushpa S., Mehta, Anant S., Mehta, Sunder J., & Makhijani, Arjun B. (1990). Bhopal tragedy's health effects: A review of methyl isocyanate toxicity. Journal of the American Medical Association 264(21), 2781-2787. Morgen, Sandra. (2002). Into Our Own Hands: The Women’s Health Movement in the United States, 1969-1990. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Morris, David. B. (1998). Illness and Culture in the Postmodern Age. Berkeley: University of California Press. Piasecki, Bruce W. (1995). Corporate Environmental Strategy: The Avalanche of Change Since Bhopal. New York: Wiley & Sons. Poletta, Francesca, & Jasper, James M. (2001). Collective identity and social movements. Annual Review of Sociology 27, 283-305. Rajan, S. Ravi. (2002). Missing expertise, categorical politics and chronic disasters – the case of Bhopal. In, Susanna Hoffman & Anthony Oliver-Smith (Eds.), Culture and Catastrophe: The Anthropology of Disaster. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research (SAR) Press. Satinath Sarangi. (1996). The movement in Bhopal and its lessons. Social Justice 23(4), 100-108. Sen, Falguni., & Egelhoff, William G. (1991). Six years and counting: Learning from crisis management at Bhopal. Public Relations Review 17(1), 69-83. Shrivastava, Paul. (1987). Bhopal: Anatomy of a Crisis. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger Publishing Co. _____. (1994). Technological and organizational roots of industrial crises: Lessons from Exxon Valdez and Bhopal. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 45(3), 237-253. Shriver, Thomas E., Miller, Amy Chasteen, & Cable, Sherry. (2003). Women's work: Women's involvement in the Gulf War illness movement. The Sociological Quarterly 44(4), 639-658. Smith, Jackie, Chatfield, Charles, & Pagnucco, Ron. (Eds.) (1997). Transnational Social Movements and Global Politics: Solidarity Beyond the State. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. Smith, Jackie, & Johnston, Hank. (Eds.) (2002). Globalization and Resistance: Transnational Dimensions of Social Movements. New York: Rowman & Littlefield. Tarrow, Sidney. (1998). Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Weisgerber, Corinne. (2004). Turning to the internet for help on sensitive medical problems: A qualitative study of the construction of a sleep disorder through online interaction. Information, Communication & Society 7(4), 554-574. Wessely, Simon. (2001). Ten years on: What do we know about the Gulf War? Clinical Medicine 1, 1-10. Wramner, Eva. (2004). Fighting Cocacolanisation in Plachimada: Water, soft drinks and a tragedy of the commons in an Indian village. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Lund, Sweden: Lund University. Zavestoski, Stephen, Brown, Phil, Linder, Meadow, McCormick, Sabrina, & Mayer, Brian. (2002). Science, policy, activism and war: Defining the health of Gulf War veterans. Science, Technology & Human Values 27, 171-205. Zavestoski, Stephen, Brown, Phil, McCormick, Sabrina, Mayer, Brian, Lucove, Jaime, & D’Ottavi, Maryhelen. (2004). Patient activism and the struggle for diagnosis: Gulf War Illness and other medically unexplained physical symptoms in the U.S. Social Science & Medicine 58, 161-175. Zavestoski, Stephen, Morello-Frosch, Rachel, Brown, Phil, Mayer, Brian, McCormick, Sabrina, & Gasior Altman, Rebecca. (2004). Embodied health movements and challenges to the dominant epidemiological paradigm. Research in Social Movements, Conflict and Change 25, 253-278. Ziebland, Sue. (2004). The importance of being expert: The quest for cancer information on the Internet. Social Science & Medicine 59(9), 1783-1793. 1 Japan and Russia, who are also members of the G8, are deserving of further investigation as well. In terms of environmental health hazards, the dioxin disaster at Minimata Bay in Japan and the Chernobyl disaster in the former Soviet Union have interesting, and previously studied, health social movement aspects.