gothicfiction

advertisement

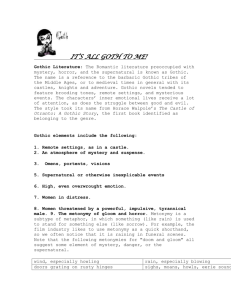

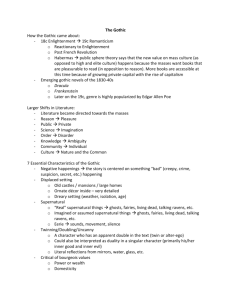

INTRODUCTION TO GOTHIC FICTION “Goth” is a term applied to various Germanic tribes who ransacked southern Europe from 376-410 CE. Because the Goths were credited with bringing about the fall of Rome and its classical culture, Renaissance and Enlightenment critics later applied the term “Gothic” negatively, to mean “medieval” or that which was considered barbaric. Medieval or “Gothic” architecture, for example, did not follow the classical ideals of simplicity, unity, and symmetry—instead, soaring towers, pointed vaults or arches, flying buttresses, gargoyles and other intricate or “wild” elements prevailed in churches, castles, and monasteries. “Gothic” gradually lost its negative connotation and was used to refer to an ancient past, often in a nostalgic way. The Gothic movement in literature, like Romanticism, is viewed as a reaction to Enlightenment rationalism, a return to the primitive. The 18th century was an “Age of Reason” concerned with classical principles and scientific progress. The novel, a young genre, was predominantly realistic and didactic. Appearing near the end of the 18th century, however, Gothic novels drew upon the conventions of the medieval (chivalric) romances that told of knights battling with magic and monsters. Gothic novels presented a protagonist’s immersion into a dark, horrific realm of some kind and reintroduced supernatural elements into fiction. Gothic tales characteristically deal with difficult-to-express issues and anxieties. Boundaries or limits (political, philosophical, sexual, etc.) are both established and challenged in Gothic fiction. Blurring or disruptions of borders are common (e.g., inside/outside, illusion/reality, masculine/feminine, material/spiritual, good/evil) and the tensions between the scientific and the supernatural are often prominent in Gothic texts. Originally called “Gothic romances,” Gothic novels were consumed by a popular audience—often women—and initially considered to be of low literary quality. The Gothic novel's “golden age” is generally cited as lasting from 1764-1840; however, the Gothic influence remains visible not only in literature, but also in film, television, music, and even dance. Conventions of the Gothic Novel: wild landscapes remote or exotic locales dimly lit, gloomy settings ruins or isolated crumbling castles or mansions (later cities and houses) crypts, tombs dungeons, torture chambers dark towers, hidden rooms secret corridors/passageways dream states or nightmares found manuscripts or artifacts ancestral curses family secrets damsels in distress marvellous or mysterious creatures, monsters, spirits, or strangers enigmatic figures with supernatural powers scientific tone (fantastic events observed empirically) specific reference to noon, midnight, twilight (the witching hours) use of traditionally "magical" numbers such as 3, 7, 13 unnatural acts of nature (blood-red moon, sudden fierce wind, etc.) Sources: Fred Botting, Gothic (London & New York: Routledge, 1996); J.A. Cuddon, Dictionary of Literary Terms (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991); Markman Ellis, The History of Gothic Fiction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2000); Thomas Woodson, ed., Twentieth-Century Interpretations of The Fall of the House of Usher (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 1969). The Ghost Story and the Horror Story: The ghost story and the horror story are influenced by Gothic novels and appear early in the 19th century. Both stories have elements of horror, but while a ghost story usually deals with the reappearance of the repressed and must have a ghost (hence the name), a horror story does not; a confrontation with something unknowable/unexplainable is at the core of the horror story. Both types of stories explore the limits of what people are capable of doing/experiencing (e.g., the capacity for fear, violence, madness) in a world where the “normal” rules of cause and effect do not necessarily apply. The stories present an attempt to confront and find adequate descriptions/symbols for deeply rooted energies and fears related to death, afterlife, punishment, darkness, evil, violence, and destruction. Hell, traditionally conceived as existing in another location or plane (e.g., Dante's Inferno), has been re-envisioned as residing in the mind or consciousness. Common Motifs: murder suicide torture madness lycanthropy (werewolves) ghosts vampires doubles and doppelgängers demons poltergeists demonic pacts diabolic possession/exorcism witchcraft voodoo SELECTED TIMELINE OF GOTHIC FICTION 1764 1773 1860 1872 1886 1891 1896 1897 Horace Walpole's The Castle of Ontronto Anna Letitia Aikin’s “On the Pleasure Derived from Objects of Terror” argues that reading about horrific events can be pleasurable although experiencing terror is not. Theories of the sublime (contradictory emotion that finds pleasure in horrible things) and catharsis (Aristotle’s term for moving the audience through pity or terror as a purgative of the emotions) are operative here. Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho (“supernatural explain’d”) Matthew Lewis, The Monk Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (written after Byron’s invitation to “write a ghost story”) Jane Austen, Northanger Abbey Dr. John William Polidori, The Vampyre Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre James Malcolm Rymer, Varney the Vampyre Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White Sheridan LeFanu, Carmilla R.L. Stevenson, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray H.G. Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau Bram Stoker, Dracula 1920 1960s- now Literary criticism recognizes the Gothic as discrete genre for study. Classic Gothic texts are republished and widely distributed. 1794 1796 1818 1819 1847