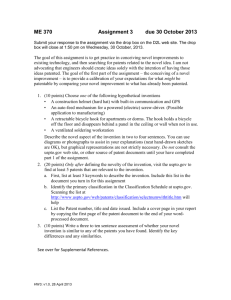

intellectual property and the right to health

advertisement