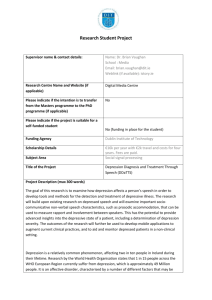

Description of Scale - The Movement Disorder Society

advertisement