MakeNumbersTalk- Cow-calf Cost&Profit Information 8-24

advertisement

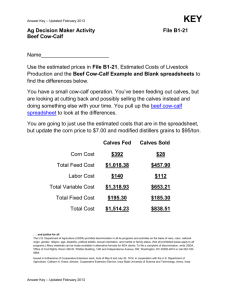

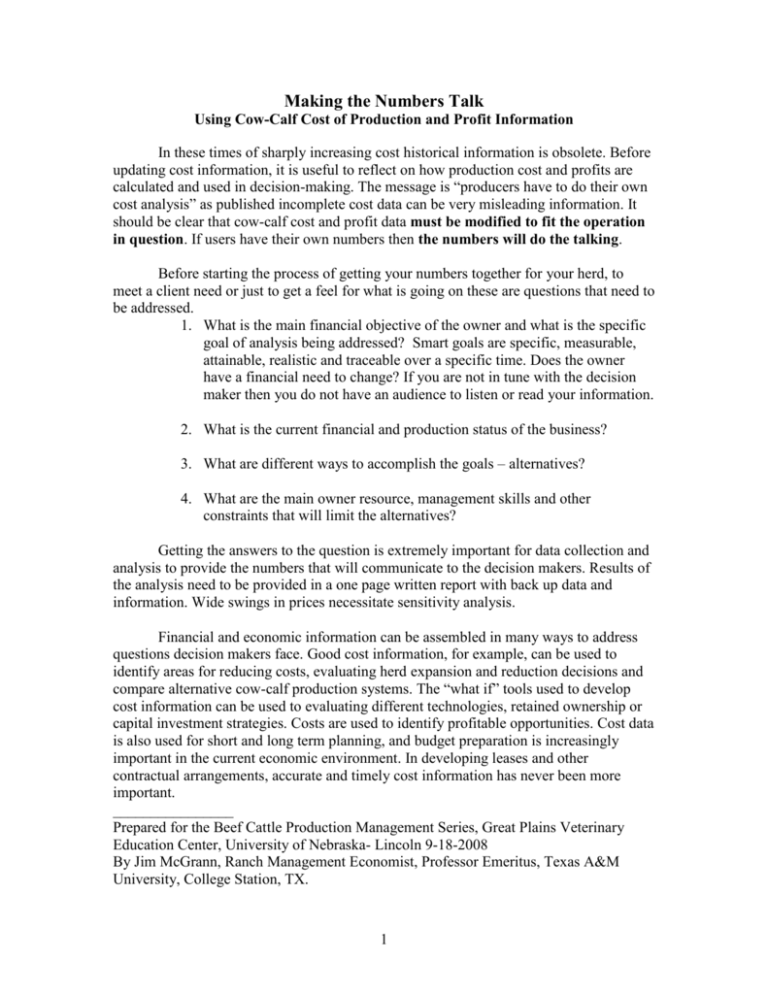

Making the Numbers Talk Using Cow-Calf Cost of Production and Profit Information In these times of sharply increasing cost historical information is obsolete. Before updating cost information, it is useful to reflect on how production cost and profits are calculated and used in decision-making. The message is “producers have to do their own cost analysis” as published incomplete cost data can be very misleading information. It should be clear that cow-calf cost and profit data must be modified to fit the operation in question. If users have their own numbers then the numbers will do the talking. Before starting the process of getting your numbers together for your herd, to meet a client need or just to get a feel for what is going on these are questions that need to be addressed. 1. What is the main financial objective of the owner and what is the specific goal of analysis being addressed? Smart goals are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and traceable over a specific time. Does the owner have a financial need to change? If you are not in tune with the decision maker then you do not have an audience to listen or read your information. 2. What is the current financial and production status of the business? 3. What are different ways to accomplish the goals – alternatives? 4. What are the main owner resource, management skills and other constraints that will limit the alternatives? Getting the answers to the question is extremely important for data collection and analysis to provide the numbers that will communicate to the decision makers. Results of the analysis need to be provided in a one page written report with back up data and information. Wide swings in prices necessitate sensitivity analysis. Financial and economic information can be assembled in many ways to address questions decision makers face. Good cost information, for example, can be used to identify areas for reducing costs, evaluating herd expansion and reduction decisions and compare alternative cow-calf production systems. The “what if” tools used to develop cost information can be used to evaluating different technologies, retained ownership or capital investment strategies. Costs are used to identify profitable opportunities. Cost data is also used for short and long term planning, and budget preparation is increasingly important in the current economic environment. In developing leases and other contractual arrangements, accurate and timely cost information has never been more important. ________________ Prepared for the Beef Cattle Production Management Series, Great Plains Veterinary Education Center, University of Nebraska- Lincoln 9-18-2008 By Jim McGrann, Ranch Management Economist, Professor Emeritus, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX. 1 The beef cattle industry is still often a predator or prey situation. It is wise to have the information to avoid being the prey. All this information improves the communication between decision makers. There has been a sharp increase in the big “5 F” costs that include fuel, fertilizer, feed, family and finance. Managing these costs is an important business management challenge. Operating capital requirement is sharply increasing. During stress periods is when new opportunities pop up for the informed decision maker! “Let the numbers do the talking” is a challenge in the cattle industry as it is less common for cow-calf producers to manage by the numbers than any sector in agriculture. Any business decision that focuses on evaluations of alternatives needs to begin with a good set of “numbers” that clearly show the current situation and then present the numbers for alternatives. Numbers must be understood by the users to really communicate. In addition, as with any communication, the users must have confidence in the numbers, and the communication has to take place in a timely manner before the decision is made. Accounting systems have to meet IRS reporting requirement but can be organized in a way to provide the financial numbers that can communicate, which is one of the functionalities of a “management accounting system.” Remember, “opinions and talk” without the numbers or mixing emotional reasons for doing things will not provide sound business management informed decisions. Talk is cheap when it is not backed by good accurate and timely numbers. Many ranchers and people around them are willing to express opinions with little information or understanding of the decision environment (historical or current situation). Having good numbers is increasingly important for communication with family members, many who have limited experience and information to judge performance. The purpose of this paper is to help users understand economic and financial terminology, basic tools and information. It is also to help understand the limitations of beef cattle published information and decision aids. The aim is to improve the quality and use of cow-calf economic and financial information so the numbers effectively communicate. The appendix includes definitions and guides in use of the information. Terminology - Definitions of Cost and Profit Terms Reviewed below are key differences in cost and profit calculations. Each has its place it is just a matter of how the data can be used to address different questions. Using the correct terminology is critical for communications for all reading the numbers. A few definitions will help explain why different sources will have different cost and return values. First, it is important to understand the calculation and the use of the word “profit” in the beef cattle sector. Profits are the difference between revenue and expenses including depreciation which is non-cash cost. It is the net return to the business equity that can be used for investing, savings, consumption or family living withdrawals. Most published costs are before income tax as calculating income tax cost is complex and highly variable between businesses. Equity change, however, is after income taxes are paid and reported in the business profit & loss or financial statement. 2 The accountants calculate financial profit by matching revenue to cash expenses plus depreciation. When doing cash accounting there has to be adjustments made for accounts payable and receivable and changes in inventories and prepaid expenses to get the timing of revenue earned and expenses incurred to match. These accrual adjustments are necessary for most agricultural producers as they do cash accounting and reporting to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). A business’s financial information is presented in the income statement or profit and loss statement. To generate the cow-calf cost for a multi enterprise business revenue and costs have to be allocated the cow-calf activity. Financial profit is the value that is used in calculating the return on assets (ROA). In addition to these financial costs, for economic costs include opportunity cost for resources (land, capital and unpaid owner operator labor and management) used in production. Opportunity cost is the value of the use of the resource in the next best use. Using an equivalent cost for hiring labor and management or using market lease return to owned land are examples of “economic costs”. Cash profit is a term used by Cattle-Fax, Drovers, Livestock Marketing and Information Center and others in the cow-calf sector. This term is a wrong use of the financial or economic term profit. Their cash number should be referred to a cash margin. This would be a signal the reader that the costs are not complete as will be clarified below. It is hard to understand why the providers of cow-calf cost and profit information under report costs. Often the incomplete data is reported without explanation that it is partial cost estimation. All feedyard closeouts report net income margin above direct costs not profit. Depreciation is a Real Cost Depreciation is an accounting method for allocating the cost on an asset over its estimated useful life. Depreciation is a significant cost for a cow-calf operation. As most operations purchase some cows, herd bulls and have vehicles, equipment and machinery. Specialized building, fencing and other improvements are depreciable assets. Depreciation is non-cash cost as no one writes a check to pay for depreciation. The check is written when the asset is purchased and then the annual cost is calculated to reflect the use of the asset over time. IRS accelerated depreciation rules that use unreasonable useful life, no salvage value or use of Section 179 to depreciate the asset in the year of purchase means the depreciation cost generated for tax purpose has little value in calculating financial cost or the business profit or loss. Table 1. is used to illustrate the difference in IRS depreciation, Section 179 and book or straight-line depreciation. The purchased cow example shows how IRS 150% declining accelerated depreciation or section 179 methods create a yearto-year variation and capital gains, as a salvage value is not recognized. By definition, depreciation cannot exceed cost. Capital gain (loss) is used to insure depreciation, and capital gain (loss) is equal to the capital asset investment cost. Using any single year’s depreciation will be highly variable based on the method chosen to depreciate and year of purchase. 3 Calculating Depreciation To correct the cash cost limitation not including depreciation or use IRS data it is best to calculate annual depreciation using straight line and estimating a salvage value. Annual Depreciation = ((Purchase cost – Salvage Value)/ (Useful Life)) Example, a herd bull costs $3,000 and a salvage value of $1,000 and useful life of 4 years: Herd Bull Depreciation = (($3,000 – $1,000)/ (4)) or $500 per year. For a $30,000 vehicle with a 100,000-mile, life and 10% salvage value used for 15,000 miles a year. Vehicle Depreciation = (($30, 0000-$3,000)/ (15,000/100,000)) = (27,000*.15) = $4,050 per year. Table 1. Internal Revenue Service Versus Book Depreciation Section Internal Revenue Service* 179 Cow Cost $1,300 $1,300 Salvage Value $0 $0 Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 Total Depreciation Capital Gains % 15 25.5 17.85 16.66 16.66 8.33 Book** $1,300 $660 % 20 20 20 20 20 $195 $332 $232 $217 $217 $108 $1,300 0 0 0 0 0 $1,300 $1,300 $640 $660 $660 $0 *IRS 150% declining balance method (half year convention) **Book depreciation 5 year straight line with salvage value based on a 1,100 pound cow at $60 per cwt. 4 $128 $128 $128 $128 $128 $0 Now it is best to ask the business CPA to run “book depreciation” for the business while running IRS depreciation. Provide them expected useful life by asset groups and expected salvage values. All capital asset management software has this calculation capability. Publishers of cow-calf cost data should set up representative operations and calculate depreciation rather than ignore these costs. The consequence of not including this important cost has to be explained. Partial numbers don’t communicate well Cost of Unpaid Owner-Operator Labor and Management Not having the cash cost for owner labor and management in cow-calf costs goes back to the IRS convention. The majority of farms and ranches are sole proprietorships. Owner operator salaries, payroll expenses or family living withdrawals are not taxdeductible costs. In a corporate business, payments to owner management are a taxdeductible business cost. Not including owner operator compensation means working for nothing and alternative sources cover the family living expenses. For the cow-calf activity, these are the two most important cost items after feed and grazing costs. The University of Illinois Farm Business Association’s 1,232 farm families enrolled in their farm record keeping system reported the average noncapital living expense averaged $60,294 in 2007 (University of Illinois Extension). Recall this expenditure included social security tax payments. To have meaningful financial or economic costs that can be compared across segments, cow-calf, stocker/feeder, feedyard and business organizations the owneroperator labor, management costs, and depreciation must be included. Using IRS Data to Calculate Cost There should be no mistake that the data generated for tax purpose is very valuable in the process of putting data together to measure financial profit and total unit cost. IRS cash accounting based data, however, is for tax purpose and determining tax liability. The Schedule F. is not a business profit and loss statement. Cash data has to be adjusted for accounts payable, receivable and prepaid expense and changes in inventories to get the timing of revenue earned, and expenses incurred to match. These accrual adjustments are necessary but not difficult to accomplish for most agricultural producers. With “book” depreciation, all is set for a meaningful management profit or loss statement that does not interfere at all with compliance for the IRS cash accounting. 5 Summary - Understanding Profit Be very cautious when using reported cattle industry breakevens, net income and profit projections. Most frequently, beef cattle breakevens do not include all costs, and profit values overstate true financial profitability. Developers of these values often ignore self-employment and income taxes, returns to management and labor and overhead costs. Truly profitable enterprises provide retained earnings that can be used for savings, capital investments or to reduce debts after all costs are accounted for. Always question what is included in cost and income reports or projections. A business must be profitable to survive financially and maintain equity. In fact, the only way a business can survive without profit is with outside earnings, gifts, or contributions to the business from outside sources. Competitiveness is measured by the ability of a business to produce and market a production and generate a profit. A competitive business generates after-tax profits. The financial progress of a business is measured in terms of the change in the business equity (assets - liabilities) or the difference between the total assets of the business and what is owed by the business (liabilities). Equity change is determined by preparing the businesses or enterprise’s beginning and ending balance sheet, accrual adjusted income statement and statement of owner equity. Change in equity the measure cattle business performance. Producers need to know if the businesses adding equity or using equity to stay in business? Having a business that is not profitable does not mean changes cannot be made to reduce losses or increase profits. Cost effective changes accomplish this. As added revenue from the change are greater than added cost. Reducing losses is increasing profit. Recall the saying “a penny saved is a penny earned”. Published Data - Explanation of Cow-Calf Cost Calculations To illustrate the reporting of cow-calf costs examples are described as well as their uses and limitations. It is not that one method is right or wrong. It is the way the data is used that makes it right or wrong for the question being addressed. Published cow-calf cost data is provided in several forms and sources a few are shown in Table 1. Most Land Grant Universities publish economic costs of production and returns. Cattle-Fax and Drovers Journal publishes cash costs derived from a survey of membership. These are not statistically based surveys but mail in responses to a questionnaire from members or subscribers. Data is from larger herds – Cattle Fax 2007 costs were from herds with an average of 768 exposed females, Drovers 376 cows owned. Less than 1% of the cow-calf operations have more than 500 cows, a little over 10% have more than 100 cows ( NASS-USDA, 2007). 6 Inconsistency in inclusion of cost in the Cattle Fax, Hughes and Drovers makes these costs non-comparable. Its also of interest of why do these sources under state costs and use data from large herds. Cattle Fax and Drovers use these numbers to be representative for the U.S. and yet use the same cash numbers to calculate what is called profit. Table 1. Comparison of Cow-Calf Cost by Source and Method of Calculation Source Year Cost $/Cow Calf $/Cwt Description Kansas State University 2008 2007 $750 $132 $119 Total economic cost Total economic cost University of Nebraska 2008 $768 $164 Total economic cost Winter hay & Aftermath grazing 85% calf crop 550 weaning wt. Harlan Hughes - "Beef" 2008 $112 Economic cost no owner operator cost of labor and management Or Equity capital cost. Nebraska & Eastern Wy. Cattle Fax 2007 Drovers - Survey 2007 Texas SPA - Stan Bevers 2007 Texas SPA - Stan Bevers 2007 $391 $84 Cash Cost only Average herd 768 cows No owner operator cost or labor or depreciation cost. U.S. $96 Cash Cost only Average herd 376 cows No owner operator cost or labor or depreciation cost. U.S. $633 $122 Financial Cost - SPA methodology as of 8/2008 for herds completed. $660 $140 Economic Cost - SPA methodology as of 8/2008 for herds completed. When comparing profits across segments of the cattle industry – cow-calf versus stockers or finishing cattle in addition to calculating profit per head the return on assets (ROA) must be calculated to have meaningful comparative performance. The investment per head for a cow-calf enterprise where land is owned is at least 15-20 times more than the feedyard investment per head capacity. Feedyards use the futures market to hedge feed and cattle, this is not reported in feedyard return data, and feedyard losses are always overstated. 7 The Standardized Performance Analysis (SPA) data is developed from individual producers’ accrual adjusted income statements providing production, marketing and both full cost economic and financial costs reports. The data is in reference to herds in the Texas that is developed one-on-one with the producers. Land Grant University Enterprise Budgets Many Land Grant Universities publish economic budgets for livestock and crop enterprises and these budgets are “full economic” costs and return budgets. Since opportunity cost for all resources are included, they are very useful for evaluating the economic profit for alternative resource use. That is for questions like using land for stockers rather than cows. Potential use of land for cash crop production versus calf grazing. These budgets are made available in spreadsheet form so it is very convenient to change the production parameters costs and prices to fit the particular situation. Since cash and non-cash costs are, clear cash of financial budgets can be prepared for the data for projections. A couple of areas that are more difficult to estimate are the depreciation of equipment, machinery and vehicles because they differ so widely between operations and overhead (telephone, property tax, accounting and legal services, utilities). Increasing in managerial accounting these costs are referred to as general and administrative (G&A) costs that in addition to overhead include the administrative cost manager. Using actual producer accounting data can be helpful for the user of these budgets. The budgets do provide a good starting place and the spreadsheet formats provide a great place to modify the budget updating process for the particular business. Most budgets are available in spreadsheet form and list inputs so costs and prices can be easily changed. For the newcomer in the cow-calf business the economic budgets are a very good place to start and all resources are included in costs. Working from this base the financial budgeting and analysis can be developed capturing cash requirements to service mortgages or other loans. Full economic cost budgets are much more useful in measuring the industry competitive position and expansion possibilities or where resources could be used for alternative production activities and generate a higher income. Use the opportunity cost concept. One important use of economic cost is to determine if it is more profitable to operate the cattle production or just lease the land. In fact, if the profit from operating is not greater than a net lease then it is time to lease if profitability is the objective. This reality is why so much of the cropland in the Midwest is leased. Leasing the land is much more profitable than operating especially, where the size of the ranch is small. 8 Cow-Calf Cash Costs of Production Are Misleading and Misused Cattle-Fax generates the cow-calf cash costs from a survey of their members. This was the 2007 survey question: 11. Cost of Production. (Cash costs per cow, not including depreciation, opportunity costs or return to management.) Feed Costs Pasture - Hay, other feed and supplement Total feed cost Operating costs – Labor - Vet, supplies. etc. - Interest expense (excluding land) Total operating costs Other costs: Fuel, utilities, etc Total estimated cash expenses per cow in 2006 Total estimated cash expenses plus non-cash expenses in 2006. (Including depreciation, opportunity costs and returns to management) When reporting costs Cattle-Fax only reports cash costs. Deprecation and opportunity costs are not included. These costs cannot be used to measure costs and profitability of the cow-calf enterprise. Revenue is not requested from the producers but calculated using estimated weaning and regional price. When using these costs it is important to understand the limitations of only cash costs. Depreciation as a cost item is second to grazing and feed cost in importance. Not including compensation to owner operator management or labor means the owner operator works for nothing. Comparing an owner operator cost to the operation that hires management is not meaningful. You cannot compare profitability between activities because having only cash costs does not provide a financial or economic profit nor total unit cost measure. It should be clear that revenue minus cash cost is not a measure of profitability. In a recent article, a Cattle-Fax writer made the following statement. “During the past eight years, margins in the packing and cattle feeding segments have gravitated around break-even levels, while cow/calf and stocker operators have enjoyed tremendous profits. Based upon Cattle-fax data since 2000, cow-calf operators have been profitable every year with an average margin of $110/Head (National Cattlemen – The Journal of American cattle producers, “Beef Industry Margin Update” June 2008, page 28).” It is most likely that the cow-calf participants in their survey hardly covered their depreciation cost let alone pay a “hired rate of return to owner labor and management”. This cash measure of profit cannot be compared to a feedyard profit that of course 9 includes depreciation and management returns as most are corporate businesses financial reports. Using only cash costs prevents a meaningful comparison between different cattle activities of segments of the industry. Per head cow-calf, enterprise cash returns to a feedyard profit per head is not correct. Having only cash cost prevents calculation of return on assets a key measure of financial performance. “Cash profit” is not, a meaningful financial or economic term. There is incomplete matching of total revenue and all expenses necessary to calculate profit or total cost. Cash costs as a measure of financial performance are also used by the Drovers Journal in their survey. The Livestock Marketing and Information Center uses cash cost plus a land lease rate for grazing. Neither includes depreciation as a cost or operator labor and management. The cow-calf sector may be the only economic activity that conforms to misrepresentation of true costs and profitability. One has to assume these information providers are aware that they are misrepresenting reality. The methodology and limitations are not properly explained. Under statement of cost and over statement of production performance in the cattle sector is very common. It’s all the way for over statement of weaning rates to average daily gain to feedyard profit and losses. It is imperative that producers calculate their own costs rather than use published information. Cow-Calf Standardized Performance Analysis (SPA) SPA is a standardized beef cattle enterprise production and financial performance analysis system. The Cow-Calf and Seedstock SPA Subcommittees of the National Cattlemen’s Association (NCA), in cooperation with the National Integrated Resource Management (IRM) Coordinating Committee, defined this cow-calf enterprise analysis system in 1991. One of the important reasons for this effort was reorganization that there was inadequate standardized cow-calf cost and production information and benchmarks. Table 2 shows SPA results for Texas that include over 400 herds and 300,000 beef cows. SPA facilitates the comparison of an operation's performance between years, producers, production regions, and production systems. The analysis is based on production cycle and fiscal year accrual adjusted financial data. Cow-Calf SPA includes performance measures for reproduction, production, grazing and raised feed, marketing, and financial and economic performance. SPA is an integrated analysis that links both financial and production performance. SPA reports both financial and economic costs and profit as described above. Financial costs include cash financial costs and depreciation. An opportunity cost is included for owner-operator management and labor. Economic reports include an opportunity cost for capital and cash lease rate for owned land. 10 Table 3. Summary of Texas Cow-Calf SPA Data by Year - 1991-2007 Return on Assets*** Calf Year Weaned Price Net Per Cost per Cost per Cost Market Wean Lb. per $/Cwt. Cow Cow** Cwt.** % % % Female 1991 $90.52 $8.30 $429.97 $92.96 4.33 2.61 79.8 414.3 1992 $85.02 $27.50 $391.90 $81.41 4.36 3.12 84.5 423.1 1993 $86.44 $7.38 $372.96 $85.99 2.77 1.65 84.8 428.4 1994 $78.99 $8.95 $384.75 $79.18 2.56 2.17 82.3 439.8 1995 $62.87 ($36.11) $360.57 $72.96 -0.53 -3.41 82.9 466.9 1996 $59.69 ($46.84) $349.77 $75.93 1.15 -0.81 84.0 456.7 1997 $79.00 ($8.18) $377.17 $81.92 0.73 -0.08 77.2 413.9 1998 $74.58 ($140.94) $494.48 $107.73 -4.85 -4.35 83.9 457.5 1999 $83.14 ($59.86) $465.06 $101.72 -3.55 -3.15 76.4 406.5 2000 $88.26 ($23.10) $449.22 $87.73 0.55 0.25 83.4 443.5 2001 $88.21 ($103.86) $516.03 $124.41 -1.47 -1.81 79.3 416.6 2002 $79.65 ($164.01) $558.98 $134.00 -4.23 -3.03 82.0 434.2 2003 $92.24 ($60.84) $516.24 $110.23 -0.75 -0.61 79.5 414.7 2004 $110.39 ($2.96) $520.98 $115.50 0.13 0.02 79.5 396.9 2005 $113.36 $47.06 $497.29 $102.25 2.76 2.19 83.1 443.4 2006 $114.36 ($48.45) $584.41 $128.38 0.35 0.61 82.5 429.9 2007 $115.97 ($16.27) $633.09 $122.24 2.22 2.08 80.7 453.2 1991-07 $88.39 ($36.01) $464.87 $100.27 0.4 (0.2) 81.5 431.7 1997-07 $96.02 ($57.32) $523.58 $113.42 (0.88) (0.78) 81.0 429.6 _____________________________________________________________________________________ __________ *1995 a disproportionate share of large herds other years resulting in a lower unit cost. **Total unit costs include all cash costs plus depreciation, operator labor and management cost plus non-cash accrual adjustments. ***Financial return on assets is financial operating returns and not land appreciation. Partial year results in 2007. The cow-calf SPA data base is managed by Stan Bevers, Vernon , Texas , AgriLife Extension, Texas A&M University, http://agrisk.tamu.edu. 7-17-08. Implementing SPA does require an extra effort as the rancher’s actual production and financial data is used. The benefit over survey data is financial, production data is complete, and the organization of data follows a standard methodology. The producers that do the SPA analysis learn a great deal about their cow-calf operation both from a 11 production as well and financial aspects. Developers of SPA had hoped to create a national database to help overcome the deficiency in complete information in the cattle industry. The most time consuming part of implementation is the getting reproduction data together because operators do not keep inventories that keep track of cows moving through the production cycle. Many producers do not keep data on exposed cows and heifers. A good monthly-reconciled cattle inventory solves this problem. The SPA information from the Texas although limited indicates the cow-calf enterprise is far from being a “highly operating profitable” activity when one includes depreciation and a market return to owner labor and management. This conclusion is consistent with the economic budgets published by the Land Grant Universities and complete financial cost and profit reporting. Appreciation of Land Annual financial or economic operating profitability calculations rightfully do not include grazing land appreciation. Due to other demands for land value appreciation has been high. This has nothing to do with the cow-calf operating earnings. If landowners can support ownership with outside sources of income, the investment has generated a good appreciation return. Of course, to realize this return the land would have to be sold. Cowcalf operators have two businesses: land ownership and the cow-calf operation. Owing land has been profitable. Operating returns from the cow-calf activity has not been profitable over time when full costs have been accounted for. Many producers can of course lease owned land, earn the appreciation return, and avoid operating losses. High Cow-Calf Economic Profit – It Does Not Happen The cow-calf sector has never been “highly profitable” from an economic operating standpoint. The activity is land based. By definition if the operating returns are high, the lease rates for grazing (opportunity cost) will rise lowering the net economic income for the landowner. Higher net income will also result in bidding up the grazing land thus lowering the net income. This is why land-grant university budgets normally show negative economic income. Now for the cow-calf landowner owning land has been profitable, as the land has appreciated over time, and has been a very good hedge against inflation, capturing some of the tax benefits and demands for recreation and life style. To realize this appreciation income the land must be sold and capital gains taxes paid. Cost effective and productive cow-calf operations will generate a higher operating ROA. Larger operations that capture the economies of scale can generate a 5-7 % ROA. In the business world, that is not a high profitable investment. A 15 to 20% ROA would be a high operating return. Land rich and cash or operating profit poor is the best way to describe the owned cow-calf operations. 12 Using Cow-calf Price and Cost Data to Project Herd Expansion or Contraction Analysts are frequently “making predictions” on the expansion and contraction of the beef cow herd because of its implications as far as supplies of feeder cattle to the finishing sector and intern beef supply. Given the structure of the sector, weather variability (especially drought conditions), the long production cycle and poor financial and economic data, the short-term projections have not been accurate. Predicting herd change is complex because of all these interrelated factors involved. The cow-calf sector has been a declining sector in number of operations at a rate of 7,000 operations a year. Beef cow numbers peaked in 1995 with 36 million to 33.1 million head in July 2008 and it is the lowest since 1990. There is approximately a one percent decline in cow-calf operations and beef cows annually. A full cost and return on asset measure would certainly show that financial performance is an important factor behind this decline. Having both economic and financial total cost and profit data across sizes of herds would give the prognosticator an opportunity to make projections that are more informed. Economic forces are causing this decline and using complete cost and returns information clarifies the long-term trend. Using only cash, cost from a members survey from a very narrow group of producers has been a poor indicator of trend. It also is not meaningful to compare the profitability of different segments of the industry. Getting in and out of cow-calf production is not like switching from soybeans to corn from year to the next. Putting a herd together takes time and quick liquidation only happens in response to severe drought conditions. When there is negative income producers use other income sources to stay in business and do not replace capital assets “live on depreciation”. As can be observed the national decline in the beef cow herd has been a gradual liquidation as a response to low or negative net income and ROA. Small Cow Herds - Lifestyle and Agricultural Land Use Taxation Herds with less than 100 cows account for 90 percent of the operations and about 50% of the beef cows, herds of less than 50 cows account for 77 % of beef cow operations. A large number of these herds support the rural lifestyle, retirees, and a part time management requirement. The USDA published a study in 2001 based on the 1997 census titled “Characteristics of Production Costs of U.S. Cow-calf Operations” that provides an excellent overview of the cow-calf industry. In many states, these small herds provide a saving of property tax benefiting from agricultural land use valuation. They live in rural areas, have the favorable agricultural land use valuation of property and can slip a few otherwise non-tax deductible costs of living into their IRS Schedule F. “Profit or Loss From Farming”. Their lifestyle is supported by non-farm or ranch earnings or wealth. Of course these operations must have non-farm income to reduce the after tax cost of these small herds. Rising fuel, fertilizer and feed will make these high cost herds less enjoyable to maintain. One alternative is to 13 lease the land to a cattle producer, reduce operation costs, and still take advantage of the favorable agricultural use valuation of land. The author has done enough of the SPA analysis with small herds to know these small herds can become very expensive. The way to run up production cost is getting into the beef cattle seed stock business and become prey to the vehicle, machinery, and feed salesperson. Operators with sufficient off ranch income can afford these small cow-calf herds. Increasing costs of feed, fertilizer and fuel will make these life-style herds more expensive. Let’s refer back to the depreciation explanation. A 40 head cow-calf producer has two bulls and one pickup. The total depreciation on these assets alone is $5,050 or $126 per cow. This does not account for other depreciable assets such as the equipment, machinery, horse and improvements all “real cattlemen” have to have. Small herd owners can use economic principles to reduce the cost of having cows. These operators need to avoid the temptation to have too much investment in vehicles, machinery and equipment. The old saying “if it rusts you do not need it” is a good rule. Location is key to gain from land appreciation for these lifestyle operations. The only small herds that have a chance of making a financial profit are those that are part of a cropping operation. The cow herd benefit from using crop aftermath and marginal land that cannot be cropped. In addition, the producer can avoid the purchase of vehicles, machinery and equipment. The cattle industry benefits from these private owners’s outside income and tax subsided cow-calf operations that produce nearly 50% of the calves. Predicting the expansion and contraction of this group of operations is difficult but increasing “5 F” costs will make small herds more expensive than in the past. If the “open space justification” for low property tax does not change small herd part-time operators do have some staying power especially near heavy populated urban areas. Cow- Calf Economics What We Have Learned Using SPA in Texas Key Things to keep in mind Over a production cycle, it is extremely difficult to make an operating profit with the cow-calf enterprise in Texas. At least 90% of the cow-calf operations are life style operations of less than 100 cows, the average sized herd 41 cows. Agricultural Use Valuation for property tax assessment is an important reason why lifestyle producers have cows. Producers in Texas have used SPA for more than fifteen years. Using SPA is a process, not an event, for producers that have participated. Change has to take place if completing SPA is useful to producers. Identified are areas where many cow-calf producers can reduce production cost. 14 Attitude – make a business management commitment, measure and monitor progress toward written goals. There must be a felt need to expect change. Top managers do the right things, get them done right and on time. Execution can never be under valued. Machinery and vehicles – minimize investment in depreciable assets. Avoid production of hay – build a barn, buy hay and minimize losses and hay use with good grazing systems. Monitor supplemental feed use and get feed quality analysis. Most small producers should buy replacements and use terminal cross bulls. Stay away from seedstock production. Minimize investment in horses if you expect the cows to pay their expense. Do not overstock grazing land, use soil testing to guide fertilizer use. Develop and intergraded systems for total resource management including wildlife. Unprofitable cow-calf operations frequently and adopt profitable or cost effective practices that will reduce losses. Have a controlled breeding season that will optimize grazing land use, minimize purchased feed and result in high reproduction. Reproduction (weaning percent based on exposed females) is the number one production factor cow-calf producers must focus on. Use proper health practices to insure sound herd health and participation in marketing alternatives. Avoid industry fads that are not cost effective. Do not spend money to reduce IRS taxes if they are not sound investments that will result in an increase in after tax equity. It does not make sense to spend a dollar to save thirty cents. Make sure there is a bank account for the ranch separate for the personal account. Location is important in acquiring land to realize land appreciation. Non-cattle uses of land are more important than grazing cattle for appreciation. The large difference in cost of production performance between herds helps validate the necessity to measure and manage for performance. Future Management - Cost Accounting, Communications and Reproduction Modern accounting software like QuickBooks™ can be set up to provide accurate and complete financial cost and revenue reporting by activity or enterprise on a timely manner and also for cash flow budgeting. Named managerial accounting this approach divides the business into different cost and profit centers to facilitate the allocation and reporting process (see reporting format in the Appendix). Costs are accumulated across phases of production so “Total Unit Cost (TUC) can be reported. This can be exported to spreadsheets for additional “what if “analysis. All can be accomplished by defining a chart of accounts that meets IRS needs as well as the information by activities. No data is better than your own data. 15 Ranchers like or respond better to reports that integrate production and financial or economic information and short concise reports. One-page reports get attention. Decision makers need the confidence in the numbers before they talk. The availability of economics and financial is tools for management are extensive. The creativity comes in applications and reporting not in developing new tools. Reproduction will always be the number one production performance challenge for the cow-calf producer. It is not the “in topic” in the cattle industry but has not improved in the past 25 years. Weaning rate based on exposed cows must be calculated to measure reproduction performance. Identifying causes of losses from cows pregnant to calving and weaning and finding cost effective ways to reduce these losses will be the driving force behind operating profitability. These numbers really talk because they communicate what is going on. Measuring reproduction over time reinforces what gets measured is managed. The beef cattle industry would be better served if it were more honest with its cost numbers. If the financial reality would be clearly communicated then greater effort may be more clearly focused on areas like “preconditioning health” that are not cost effective. Price premiums are reported but the full costs and net margins are not correctly communicated. They seldom communicate the added management requirement and price risk and low or negative income margins. In reality, the pharmaceutical and feed companies need to go back to the drawing board and do more research to find vaccines that are more effective, better educate and motivate proper use of products and find ways to shorten the effective preconditioning period. The reason producers do not precondition calves is because it is not cost effective, administrate products correctly, worth the cost and effort, when calves are not retained. The producer’s numbers are talking and they say do not buy that practice if you do not retain ownership. How much research and effort is expanded on ways to improve beef cattle reproduction? It is so easy to get by with fake undefined 90 % calf crops. Reproduction has not improved in 25 years. Responding to meet the market demand in a way that optimizes the use of the grazing resources and high reproduction performance will be a driving force behind cowcalf producer success. High input costs and narrow margins call for superior management information and cost effective decision-making. The old saying “you manage what you measure” put a focus on complete cost and profitability measures. Those who use written businesses plans and focus on implementation – execution, can accomplish goals. With quality numbers let the numbers do the talking. 16 Appendix A: Cost Terminology and Use for Decision-Making Cost management requires measuring cost and using cost information in decisionmaking. Producer’s information systems must generate their business cost information. Published costs are seldom complete. Frequently the cost information serves the publisher’s interest rather than providing objective information. Reality is that each business has different commodity costs. Identified in this appendix is application of cost and net income information. This is a reference to use as a reminder when making the numbers talk. Cost Competitive and Brands It is well accepted in agriculture that being competitive in the commodity world requires being a low-cost producer. It is recognized that even if products can be differentiated as is accomplished by product branding, the competitive advantage will not be achieved if production is not cost-competitive. A niche product, if successful, will eventually become a commodity. Total Unit Cost As will be pointed out, one cost will not meet all cost management information needs, however, Total Unit Cost (TUC) of agricultural commodities produced is one of the most important costs for agriculture. Total unit cost is valuable information to decision makers in that TUC is a measure of production and management efficiency, managerial ability and competitiveness. TUC is vital information in commodity price negotiation. Combining TUC with revenue provides production and operating margin information valuable for addressing resource allocation decisions, measuring performance, and investment opportunities. Producers frequently request TUC information to compare to historical data and project commodity prices to address marketing and resource use alternatives. Benchmarking commodity TUC within the business and for participation in regional and national comparative databases requires a consistent measuring of cost calculation within and between commodities and fiscal years. Total unit cost (TUC) is a sum of the direct and indirect production costs, general and administrative cost or the total operating cost plus finance cost divided by total production for the commodity production and marketing cycle. For many commodities, these costs for the primary product are adjusted for secondary revenue. Secondary revenue is revenue that is generated from production of a commodity that is a by-product or joint product from production of the primary commodity. Examples are cottonseed where lint is the primary commodity; cull cows, wheat straw, corn stocks, etc. Total production costs are adjusted by revenue-cost adjustment to calculate the total adjusted cost of production and total unit cost. TUC is reported on a per tax basis. 17 Negotiating Cost Plus Commodity Prices The importance of accurate TUC increases with the growth that integrated production and marketing activities in agriculture through alliances or contracts. This is especially true for negotiation cost plus pricing. If TUC is not complete, the negotiated cost plus price will not provide the negotiated net margin or return to equity. The methodology followed in calculation of the cost plus arrangement must be clearly stated in the agreement. One of the clear shortcomings in using TUC and cost plus arrangements is that TUC does not reflect the capital investment associated with TUC or the production risk associated with the commodity. For example the cow-calf producer that has a $4,000 investment per cow to produce a calf for a TUC of $120 per cwt once a year and nets $50 per cow (a 1.25% return on assets, ROA) cannot be compared to a feed yard with a $250 per head capacity that is turned over 2.2. times a year plus 30% equity or $200 in cattle with a TUC of $95 per cwt and netting $30 per head ($66 per year)(an ROA of 14.6%). Cost plus pricing should be negotiated with both TUC and ROA information. Price negotiators need to know TUC, net margin, and return on assets when entering an arrangement. Decision makers need similar information in consideration of internal commodity transfers pricing and retained ownership of cattle. Definitions and Notes on Using Cost Breakeven Cost is a non-standardized “selection of costs” divided by the amount of saleable product. Cost included must be defined before breakeven is useful information to decision makers. In the cattle, industry breakevens are used very loosely and are seldom full cost calculation. Capital Asset Purchase is not a cost, but the acquisition of a non-current asset with a useful life of more than one year. The cost of a capital asset is shown in annual depreciation. Capital purchase does represent a cash outflow at the time of purchase or when loan payments are made if the purchase is financed. Cash is out-of-pocket costs that are not the full costs of production, such as non-cash depreciation, adjustments for change in prepaid expenses, accounts payable and receivables and accrued interest and tax costs. Capital Purchase is not a cost, but the acquisition of a non-current asset with a useful life of more than one year. Capital purchase does represent a cash outflow. Economic Cost is, in addition to the financial cost, an opportunity cost that is charged for owned land (what it could be leased for) and owner equity capital. Opportunity cost represents the return that could be received for a resource in its next best use. Economic cost represents the cost if all resources earned their opportunity cost. Financial Costs are generated in the accrual adjusted income statements or total unit costs reports. They include cash costs, depreciation, and non-cash adjustments, such as accounts payable, accrued interest, etc. The financial cost does not include opportunity cost of resources. Owner/Operator Labor and Management is the cash withdrawals paid by the operation to the family. These are family living withdrawals that should be for 18 the production cost calculation at a level equivalent to the salary required to hire a non-family member to provide an equivalent service. Actual withdrawals in excess of this amount must be considered capital distributions in order to reconcile the retained earnings and statement of cash flows. Family living withdrawals are used to not only calculate cost of production, but return on assets, return on equity, and repayment capacity as well. Opportunity Cost is the value of a resource in its next best use. This is a powerful concept in thinking about what to do. Leasing land or operating a production activity is a good example where opportunity cost is used. Sunk Costs are historical costs that cannot be changed. When calves are weaned the costs of production are sunk costs. These past costs are irreverent in terms of the next decision. To retain ownership depends on the added cost and revenue from the next phase above what cattle can be sold for not the weaned calf cost. Total Unit or Full Financial Costs include direct and indirect production cost, general and administrative, and finance costs. Variable Cost is a cost that varies with amount of production and can be eliminated if the production is stopped. Examples include purchased feed, fertilizer and seed. If an activity cannot generate income in excess of variable costs then losses will be minimized by stopping production. In other words an activity must contribute to fixed costs or stopped. Economic Principles and Costs Before discussing costs and profits, it is valuable to review some basic economic principles and the reason knowledge of costs and profits are essential for informed decision making. Management is essentially the process of solving the problem of how to allocate available resources to meet the goals of the business. All problems of resource used involve one or more of three fundamental economic principles. They are discussed more fully in the following sections, but briefly, these principles are: Increase the use of an input as long as the value of the added output (that is, income) is greater than the added cost. Substitute one input for another input as long as the cost of the substituted input is less than the cost of the input that is replaced, and the level of production is maintained. The substitution can be a complete replacement or simply a change in the mix of products. Substitute one product for another product as long as the value of the new product is greater than the value of the product replaced and the total cost is constant. This substitution can also be a complete replacement or a change in the mix of products. 19 These principles will be sufficient for all planning if the manager has unlimited resources and perfect knowledge. Since this is not the case, three additional ideas must be introduced as aids to the decision making process: If resources are limited, use each unit of resource where it will give the greatest returns. The value added by the last unit of the resource is the same for each of its alternative uses. When alternatives involve different periods, compare the alternatives based on the present value of the resulting cash flows. Otherwise, take into account the time value of money. When risk and uncertainty cloud predictions, different levels of prices, costs, and yields should be used to evaluate the potential variation in expected income and cash flow of alternatives being considered. The Law of Diminishing Returns Keep in mind the physical law of diminishing return is helpful when thinking of what can be expected from the use of additional levels of production inputs. The physical law states, “as successive amounts of the variable inputs are combined with a fixed input in a production process, the total product will increase, reach a maximum, and eventually decline.” This physical relationship explains why, unless an input is free, it is not profitable to maximize production since the last unit of input will not increase output enough to pay the added cost. This law is easily observed in agricultural production examples, as when more nitrogen is to pastures, more irrigation water is used, and cattle are finished to heavier weights. Eventually each of these actions will become less beneficial. Adding more nitrogen will eventually cause a decline in production, adding more water will cause crops to flood, and the cattle feed efficiencies will start to decline. Cost Effective Decisions For a decision or an alternative to be “cost effective,” the added revenue must be greater than the added cost, or the cost reduction must be greater than the revenue loss. These are the two criteria that determine if a decision is cost effective or not. In economic terminology, marginal revenue (added revenue) must be greater than marginal cost (added cost). A business can be unprofitable yet have many profitable or cost effective alternatives to reduce losses – increase profits. The key to planning for cost effective decisions is very dependent on the production and cost information and the way this information is organized for analysis. Information must also be timely and understood by the decision makers. 20 By definition, “cost effective” decision-making is planning involving an unknown or a risk. The best information, particularly cost information, is the cost generated from past activities. This is where the management accounting system can be profitable to the user. The accounting information provides the decision maker the information to prevent mistakes by choosing the correct course of action. If the data and information generated by the accounting management information system is not used, it, of course, cannot contribute to assisting decision makers. You Achieve Nothing Breaking Even through Retained Ownership You achieve nothing financially by breaking even in backgrounding or feeding cattle. Yet, retained ownership and feedyard projections most often calculate breakeven as if it were the ultimate goal. It is extremely important to understand what is included in the cost to arrive at breakeven or net returns. Most calculations only include the feedyard’s direct cost of production, and they calculate the feedyard net margin. Nothing is included in the cost to cover indirect or overhead costs, the owner’s labor and management (living withdrawals) or taxes. Your business will go broke if there is no income to pay overhead costs. Many producers must have something to live on. If you earn a taxable income, self-employment taxes and income taxes have to be paid. Financial profit is properly defined as return to the producer’s equity capital at risk after all direct, indirect, and management costs (owner operator equivalent to living withdrawals) are paid. Revenue minus direct cost is the gross margin. When doing projections or evaluating closeouts, always include the cost of a portion of the overhead and indirect costs (phone, utilities, accounting, and secretarial services) of the business plus returns to owner’s management and labor. The latter can be arrived at by estimating how much it would cost to have a non-family member perform the labor and management activities. A review of your overhead costs and family living withdrawals in past years can provide good information for projections. Add these costs to the direct cost to calculate your breakevens. Consider these costs as a margin that must be covered to justify taking on the additional management responsibility. In projections, establish your target net return and determine what sale price is necessary to cover total costs to justify taking on the additional risks. It is good to consider at least three levels of possible outcome (pessimistic, likely, and optimistic prices). Calculate what the target net return to risk (profit) and equity capital will be for each price situation. Always remember you achieve nothing by attaining breakevens that only include the direct cost of production. Most cattle producers have sustained considerable equity loss in the past years. Many need to use caution as well as risk management tools to avoid further deterioration of their financial position. Recovery of equity is a painful process requiring top management. Not only when margins are narrow, but also when income is generated that could rebuild equity. A good percentage first must be paid for self-employment and income tax. 21 Many producers need a guideline to help them establish the value of their managerial services. The following is a suggested approach. Normal total farm or ranch professional management fees will run between five to ten percent of the gross income for yearlong management. Beef cattle would be on the lower end of the range, whereas intensive crop production is on the upper end. Operational management activities are performed in the feedyard and the cost is included in fees paid. The marketing and financial analysis and associated decisions are the responsibility of the cattle owner or manager. A reasonable goal would be to charge five percent of gross income adjusted for the average days on feed for owner management. For example, cattle on feed for 180 days would accumulate a management fee of 2.47% (180/365 5%). For a 1,250-pound steer at a $95/cwt price (or $1,188), this would be a management cost of $29.33 per head. On a pen of 100 head of steers, management would be paid $2,933. In order to generate a modest full time salary of $50,000 more than 1,700 head of cattle must be fed. In the case of backgrounding or preconditioning calves, the producer-manager must take care of the operational activities as well as analysis and decision-making. This is an intensive activity in terms of management input. Suggestions are to use ten percent of gross income adjusted for days backgrounded. For example, backgrounding a 600pound steer worth $720 for 45 days would cost $8.90 per head (45/365 10% $720). The returns to management would be $890 on a 100 head herd or 5,600 to earn $50,000. Using Cost Calculation to Reduce Cost Experience using the SPA system has pointed out these opportunities for reducing cost of production: Know your cost of production and update cost calculations in a timely manner. Express on a per head of breeding cows and per cwt. of calf weaned basis so the values serve as reference points (i.e., turn cost data into meaningful management decision information). Anticipate in advance what costs should be - plan for cost control. Analyze cost by exception and identify either extraordinarily large or small cost items for cost control or expenditure opportunities. Clearly identify which costs can be managed or controlled. When deciding to reduce cost, determine whether the reduced cost results in a greater reduction in revenue. When increasing expenditures, determine if the added cost will be covered by added revenue. Ensure that meaningful decision and performance evaluation information gets back to those who generate data. All employees need to see performance information, and everyone needs to provide ideas on how costs can be reduced. Budget for a profit based on a complete cost of production including indirect or overhead costs. Breaking-even is not a profit goal. Market for a profit including a return to owner management and labor, not just a direct cattle and feed cost breakeven monitor cattle markets carefully and budget marketing alternatives frequently. 22 Develop marketing alliances and merchandise cattle to bring the top dollar by evaluating all market alternatives. Invest in profitable assets and technologies. Eliminate assets that do not provide for profitable returns. To minimize input cost, use volume and seasonal discounts. Make sure capital investments are financially sound. Do not invest for the sole purpose of reducing taxes. It seldom makes financial sense to spend a dollar to save income tax. Remember, if you are not paying IRS income taxes, there is a good chance that your business is not profitable. After-tax profitability keeps you in business. Find ways to empower your employees to increase their participation in decisions and be more accountable to business objectives. Work on communication with everyone in the business. Written, accurate and timely summary information is most likely to be used. A summary one page written report backed up with the detailed analysis is very effective. Make decisions based on your information and analysis, not on emotions or others’ opinions or use published cost and profit information. Record and monitor supplemental feed use and cow condition scores. Prepare accrual adjusted income statements (i.e., cash income and expense plus adjustments for inventory changes, prepaid expenses, accounts payable and accounts receivable) to measure the business profitability. Develop written business plan with specific goals, project financial statements and cash flows and production plans to achieve these goals. Update these plans at least annually. Execution of the plan is the key. It is getting things done right and on time. Evaluate cash withdrawals from the business for family living or other activities. Answer the question, “Can the business equity be sustained at the level of current and projected withdrawals?” Challenge researchers, Extension, private firms and consultants to provide sound economic evaluations of their proposed changes in technologies and management practices. Specific target areas for reducing cost of production include: Supplemental feed cost. Make sure the nutrition program is correct for cows of different condition, and reduce feed waste. Cost of raised feed. Often, it is cheaper to buy, rather than raise, your own feed. Efficiency of the grazing system. Improve it, as this is a low-cost feed source. Unnecessary machinery and vehicles. Sell them, and the proceeds from the sale can be used in a variety of productive ways, including the purchase of more efficient equipment or the reduction of debt. Planning vehicle use to minimize mileage. Keep a logbook on vehicle use and record use when fuel is added. Insurance policies. Review them to insure coverage is at the lowest cost. Depreciation schedule. Is it complete and accurate? 23 Use qualified CPA services. Spend the extra money to receive managerial financial statements. Your tax forms do not provide an accurate measure of profitability for the business. Spend quality time with your CPA. Review your managerial financial statements and your tax management efforts at least three times year. Historical financial statements. Summarize them to see if better interest rates can be attained from a different lender with your documented financial record of accomplishment. Cattle health management program. Review with a veterinarian that understands the production and economics of your business. Overhead costs. Review to see what expenditures are necessary. Keep the tax appraiser informed. Do not avoid the opportunity to argue your property valuations. We are now in the age of the management of the five “F” fuel, feed, fertilizer, family and finance. Focusing if cost effective management of these “F” is be a challenge for the manager that needs to make a living in the cattle business or have a goal to make the ranch cash flow. Managerial Accounting Commodity Financial Reporting There are many formats to organize financial information for production activities. What is shown below is a managerial accounting-reporting format. The profit and loss (P & l) or financial statement reporting is much more standardized. However, the information is not as useful for activity analysis. A suggested format is shown below that address the components of costs and fits data is commonly available. One can communicate at what level the information reaches. The definition of each level follows. Definitions for Management Accounting Report Terminology Revenue is revenue that is identifiable with the commodity produced. Examples are wheat sales with protein or seed premiums and finished hogs or cattle with associated discounts or premiums, hedging income (cost). Revenue would also include farm program payments that are directly related to the quantity of commodity produced. Selling costs are incurred during the actual selling process. Examples include commodity check-off fees, transportation of product to market, and commission charges. Most selling expenses are identified with the sales of the commodity. Sales costs also include marketing costs including storage and conditioning of product for sale. Revenue — cost adjustments is revenue that is generated from production of a commodity that is a by-product or joint product in the production of the primary commodity. The revenue cost adjustment should be net revenue after accounting for selling costs. Examples are cottonseed (where lint is the primary commodity); cull cows, wheat straw, corn stocks, etc. Revenue — cost adjustments within a center report includes the cost of sales for second inventory sold and the cost basis 24 in breeding stock to account for capital gain (loss). Total production costs are adjusted by this revenue to calculate net production cost. Commodity Production and Marketing Cycle Report A Revenue B Revenue - Cost Adjustment C Direct Production Cost D Cattle Transfer in Cost between phases of production E Cattle Cost in this phase F Cattle Death Loss G Total Direct Cost H Indirect Production Cost I Total Indirect Cost J Total Production Costs (G + H) K Net Production Cost (J – B) L M N Production Margin (A – K) General and Administrative Cost Operating Margin (A – K – M) O Financing Cost P Net Cost (K + M + O) Q Net Margin (A – P) Cost Summary Net Production Cost (K) Operating Cost (K+ M) 25 Total Cost (K + M + O) Production costs are costs incurred in the production process to bring commodity t the point they are ready for sale. Direct production costs are costs that can be identified with the particular production activity. This would include such items as purchased and raised feed, veterinary fees, and incoming base costs (raised or purchased). These costs can be directly traced to the production activity and would cease when the activity is dropped. Indirect production costs are costs that are common to more than one production activity. These costs are assigned to production or support operations cost centers then allocated to production or profit centers as indirect costs. Examples of indirect or support center costs include labor, machinery and equipment, irrigation, and production overhead. Total production costs include direct and indirect production costs. Net production cost includes direct and indirect production costs, adjusted by revenuecost adjustment. Production margin is a value reported in the profit center or total commodity activity for subtracting production cost from net revenue. This is the income margin that is available to pay general and administrative and finance costs. The net, after income tax is paid, will be returned to equity for retained earnings or capital distribution. General and administrative costs (G&A) include business office, legal, accounting professional fees, liability insurance, and management information system (MIS) costs. Operating margin is the net primary income minus the total adjusted cost of production minus the Sales and General and Administrative costs. Total operating cost includes total production costs plus general and administrative costs. Finance costs include interest and any other financial charges associated with financing activities. The financing section includes both interest expense and interest income. Total adjusted cost before tax includes total operating cost plus finance costs. Total adjusted costs are utilized in transfer valuations within Commodity Production and Marketing Cycle reports. Total unit cost calculation requires subtracting cost-adjusting revenue from total production cost and adding sales, general and administrative and financing costs. Total Unit Cost is adjusted total cost divided by total production. Net margin is the revenue minus net costs of production, general and administrative, and financing costs. This is a measure of net income before income tax to equity. Supporting Terminology Cost of sales (COS) are costs that are accumulated and inventoried until the product is sold. Then these costs are expensed through the income statement cost of sales or cost of goods sold. Cost of sales cattle is the original transferred in or purchased cost (inventory) and the portion of non-cattle cost calculated by the number of head days and head day cost during the reporting period. The remaining basis in breeding stock sales is recorded as cost of sales. 26 Death loss cost includes production costs and incoming price. The death loss line item will be equivalent to cost of sales. Its in payweight to out payweight, deads in. Financial Statements – Their Connections The financial progress of a business is measured in terms of the change in the business equity (assets - liabilities) or the difference between the total assets of the business and what is owed by the business (liabilities). Figure 1. below is good to keep in mind when reviewing financial position and performance. Beginning Balance Sheet Assets - Liabilities Equity Ending Balance Sheet Accrual Adjusted Income Statement Assets - Liabilities Equity After Income Tax Net Income (Retained Earnings) Beginning Equity Change in Equity Ending Equity Figure 1. Relationship Between the Balance Sheets, Income Statement and Equity Key Financial Statement Formulas Equity = Assets - Liabilities Assets = Liabilities - Equity Beginning Equity + Change in Equity = Ending Equity 27 Retained Earnings = Net After Tax Income from Operations - Interest + Gain (Loss) in Capital Sales - Withdrawals – Distributions Change in equity is after income tax is paid and after withdrawals and distributions. Equity change is determined by preparing the businesses or enterprise is beginning and ending balance sheet, accrual adjusted income statement and statement of owner equity. Change in equity is the measure of business performance. Net after income can be retained in the business, with drawn for consumption, distributed to owners or invested in another business. There is likely no more important document to prepare accrual adjusted financial statements but with cash accounting for IRS tax reporting few ranches have these reports prepared. It would be progressive to have the accounting profession step forward and develop these reports for famers and ranchers. Reference: Short, Sara D. “Characteristics of Production Costs of U.S. Cow-calf Operations”, USDA-ERS Statistical Bulletin Number 974-3, November 2001, www.ers.gov. Lattz, Dale “Farm and Family Living Income and Expenses for 2007”, Farm Economics Facts & Opinions, FEFO 08-12, June 27, 2008. www.farmdoc.uiuc.edu National Cattlemen – The Journal of American cattle producers, “Beef Industry Margin Update” June 2008, page 28).” 28