The sentiment was growing clear. The Russian people wanted

advertisement

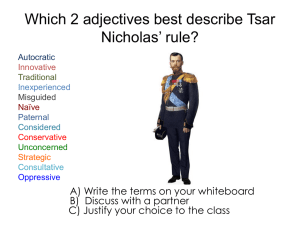

The sentiment was growing clear. The Russian people wanted change. They were reaching for democracy and representation while the last major autocratic power in Europe struggled to maintain its archaic laws and institutions.1 The Russian Revolution was a defining moment in the lives of the Russian people. A number of events in the years prior to 1917 would help lead Russia down the revolutionary path. The famine crisis in 1891; the smaller, lesser known revolution in 1905; and the devastation of World War I, all contributed to the agitated state of the masses. But underlying all these events was the tsarist regimes inflexibility and drive to maintain the autocratic Russian way of life that had been in place for centuries. In order to understand Tsar Nicholas II and his government’s role in these events it is important to look at how both viewed autocracy and each other. With this information it is then possible to see how Nicholas and the autocratic regime affected the aforementioned events and contributed to the demise of their own government. The autocratic administration had been established long before Nicholas succeeded the throne, “the day-to-day functioning and decision making of autocratic bureaucracy and its interactions with the autocrat, constituted the structure of autocracy within which the ruler had to operate.”2 According to Andrew Verner, the view of Konstantin Pobedonostsev, tutor of the two previous tsars, was that it was the individual ruler, not the laws or institutions of the state that had the largest impact on the government and people. Therefore, “success greatly depended on the personal qualities of the monarch, his mentality, vision, and determination, and on the way these were perceived by others.”3 Only a ruler who understood his role in the autocratic system 1 Rex A. Wade, The Russian Revolution, 1917 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 1. 2 Andrew Verner, The Crisis of Russian Autocracy: Nicholas II and the 1905 Revolution (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1990), 45. 3 Verner, Autocracy, 56. “could restrain the disruptive and discordant tendencies and lack of unity inherent in this system and impose on it a sense of direction and coherence.”4 Thus, Nicholas’ personality had a direct affect on how his government was viewed. He also picked the senior members of his bureaucracy. He tended to look passed a man’s accomplishments and qualifications, choosing instead to pick men based on their appearance and acts of loyalty.5 Rex A. Wade explains in The Russian Revolution, 1917 that this was a difficult task even for more capable rulers like Nicholas’ father. But Nicholas wished to maintain the autocratic rights that rulers before him were privileged to.6 Many of the men that made the public policy that affected the Russian people, the men that Nicholas chose were not capable of the job of running a country. In addition, Verner, explains that Nicholas was a bad judge of character.7 Orlando Figes, in his book The People’s Tragedy, adds to this viewpoint by explaining that Nicholas felt he needed to keep his ministers weak and constantly pitted them against each other to keep them divided. To Nicholas, this was vital to his autocratic rule. He became jealous of ministers who grew powerful. The capable ministers, the ones Figes believes could have saved the tsar and his autocratic rule in Russia “were forced out in this fog of mistrust.”8 It was only the “grey mediocrities” that survived for a good length of time in the influential offices.9 Verner argues that Nicholas was trapped by the structure of the autocratic Russian government and that he rebelled against the responsibilities imposed on him by the autocratic 4 Verner, Autocracy, 56. Verner, Autocracy, 57. 6 Wade, Revolution, 1917, 2. 7 Verner, Autocracy, 57. 8 Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891-1924 (New York: Penguin Books, 1996), 22. 9 Figes, Tragedy, 22. 5 system. This, in Verner’s eyes led to the image of Nicholas as weak, passive, and indecisive.10 There are grounds to support this claim, as Hélène Carrère d’Encausse wrote, “It is remarkable that this man who was so easily influenced, whose character was so weak, really concentrated all his political energy defending [autocracy] in speech and in action up to the moment of his abdication.”11 Scholars agree to Nicholas’ stubbornness and his ignorance to many issues regarding his people, which lend credence to this way of viewing the last tsar of the Russian empire. While he probably did feel pressure by the autocratic structure of the government, and was kept in the dark about aspects of his government and his people, this view gives Nicholas too little credit. It is true; Nicholas II was unprepared to become tsar. The sudden death of his father from kidney disease in 1894 left little time for Nicholas to learn the role of ruler that he had never wanted.12 While at his father’s deathbed he is said to have exclaimed to his cousin, “What is going to happen to me and all of Russia? I am not prepared to be a Tsar. I never wanted to become one. I know nothing of the business of ruling.”13 But once Nicholas was crowned Tsar, he wanted to have the same power his father had. He made it clear from the beginning of his reign that he would follow the autocratic ways of his ancestors despite the call for change in policy. His reply in 1894, soon after coming to power, to the zemstvos, who were looking for representation in domestic policymaking, followed this plan: …voices have been raised expressing demented dreams about the participation of representatives from the zemstvos in the conduct of affairs. Everyone must know that, devoting all my strength to 10 Verner, Autocracy, 69. Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II: The Interrupted Transition (New York: Homes & Meier, 200), 46. 12 Figes, Tragedy, 18; Wade, Revolution, 1917, 1. 13 Figes, Tragedy, 18. 11 the welfare of the people, I will maintain the principle of autocracy as firmly and as constantly as did my unforgettable father.”14 Carrère d’Encausse went on to conclude that by January 1895, Nicholas II had cemented his idea of autocracy. He was heir to the long line of Romanov rulers, and “thought of himself as the guardian of a tradition, the tradition of autocracy, of the duty of the monarch to preserve it and to transmit it, intact, to his heir.”15 Nicholas, convinced that the rest of the population felt the same as he did toward autocratic rule, thought, “the advanced ideas that he had rejected so forcefully expressed the views of only a few misfits and cranks.”16 Nicholas’ division of his bureaucratic leaders caught up to him in the final years of his reign and resulted in an ineffectual leading of governmental affairs. Figes contests that fault lay strictly with Nicholas, “If there was a vacuum of power at the centre of the ruling system, then he was the empty space.”17 Figes places responsibility solely with the tsar, insisting that while he should have been delegating power he “indulged in a fantasy of absolute power. In a sense, Russia gained in [Nicholas] the worst of both worlds: a Tsar determined to rule from the throne yet quite incapable of exercising power. This was ‘autocracy without an autocrat.’”18 The famine crisis came out of the crop failure of 1891. Bad weather was the culprit for the failure of the crop. The seeds were planted in a very dry autumn in 1890, severe frosts set in early with very little snow to protect the crops during the winter, and drought overtook the sprig and summer months.19 No rain fell for 96 straight days in Tsaritsyn, 79 days in Kazan, and 100 Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 45. Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 46. 16 Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 46. 17 Figes, Tragedy, 23. 18 Figes, Tragedy, 23. 19 James Y. Simms, Jr., “”The Crop Failure of 1891: Soil Exhaustion, Technological Backwardness, and Russia’s ‘Agrarian Crisis,’” in Slavic Review 41, no. 2 (Summer, 1982): 238. 14 15 days in Orenburg.20 The southeast of the Russian state received 40 percent its normal amount of rainfall and eastern Russia had 38 percent less than its normal amount.21 The harvest for 1891 that the peasants so desperately needed was small and had been scorched by the sun in all those rainless days.22 In fact, “the harvest of all cereals was nearly 25 percent lower than the average harvest for the period 1883-87. Harvest of the two principle cereals, rye and wheat, were respectively 63 percent and 79 percent of a normal year.”23 Seventeen provinces were affected by the crop failure—thirty-six million people—in an area “double the size of France or equal to the entire American Midwest, from Ohio to North Dakota.”24 Those with the strength left their homes hoping to find somewhere better, somewhere with food. ‘Famine bread’ remained as the staple food for those who stayed. Horses were fed the thatched roofing off the homes peasants’ homes for there could be no harvest next year without horses. Things got worse, cholera and typhus hit the area. A half a million people would be dead by the end of 1892.25 The Russian government26 refused to even recognize a famine existed at first. Food deliveries were postponed until the government could ascertain through ‘statistical proof’ that famine victims could find no other way to feed themselves. Only thirteen million of the thirtysix million people living in affected areas received aid from the government. Newspapers were not allowed to report on the famine. Cholera victims were forced to leave their homes and travel Simms, ‘Crop Failure’, 241; Figes, Tragedy, 157. Simms, ‘Crop Failure’, 241. 22 Figes, Tragedy, 157. 23 Simms, “Crop Failure”, 237. 24 Simms, ‘Crop Failure’, 237. 25 Figes, Tragedy, 157. 26 This is the government of Alexander III who was in power during the crop failure and famine. Any reference to the Tsar and agrarian crisis will refer to Alexander unless otherwise specified. 20 21 to distant quarantine centers. The sight of medical authorities made villagers panic-stricken and riots broke out that had to be suppressed by troops. It was not until November of 1891 that volunteer relief organizations were allowed to mobilize.27 The government decided to postpone a cereal export ban for an entire month, which allowed the cereal merchants to get their cereals out to foreign markets. This outraged the public that saw that cereal as food for the people of Russia. “As the government slogan went: ‘Even if we starve we will export grain.’”28 The liberal left began to cry for reform as they blamed the tsarist regime for the crop failure and famine. They painted “a gloomy view of agrarian conditions” which became a “popular stereotype” for the famine crisis. Many; including Plekhanov, Karyshev, and Solov’ev; wrote about the backwardness of farming techniques and blamed the crisis on soil exhaustion. These problems stemmed from the peasants’ inability to pay taxes and make proper use of their land. By blaming these issues, the left was really placing liability with the tsarist government. 29 High taxation would leave the peasants with a lower standard of living; this is something that most scholars can agree upon. It is arguable whether taxes played a part in the agrarian crisis, but it did affect the peasantry. That in turn played a role in the peasants’ view of the Tsar and the government. And the “fiscal policy of the state” was blamed for the “economic decline of the peasant.”30 Already growing feelings of animosity between different groups in the Russian population were only exacerbated by the crop failure and famine crisis. Figes, Tragedy, 157-158; Simms, ‘Crop Failure’, 237. Figes, Tragedy, 158. 29 Simms, ‘Crop Failure’, 237-238. 30 James Y. Simms, Jr., “The Crisis in Russian Agriculture at the End of the Nineteenth Century: A Different View,” in Slavic Review 36, no. 3 (September 1977): 379-380. 27 28 Once the general public was allowed by the government to help in the relief effort, people from all over came to the aid of the starving peasant. Count Leo Tolstoy stopped writing to help in the effort and got his family involved, as well. Doctors, along with members of many professions, volunteered their time to help the starving peasants, joining one of the many volunteer organizations created to help with the effort. The Free Economic Society was the largest of these bodies.31 And as Figes viewed it, “the guilt-ridden public, serving ‘the people’ through the relief campaign was a means of paying off their ‘debt’ to them.” But the famine crisis did something more to the public, it “activated and politicized” them; the “old bureaucratic system had been discredited” and “the conflict between the population and the regime had been set in motion.” But according to Figes, this was only a part of a larger change in society that began in the 1890s and would flow throughout the revolution in 1917. The tsarist regime was no longer “the only organized force” in Russian society.32 Opposition was growing to the Tsar and to the entire idea of autocratic rule. In the years following the famine crisis the peasants’ general well being would increase. It was not “an unending spiral of decline to ruin and destitution” in the closing years of the nineteenth century.33 But the Russian people were becoming more outspoken. More and more people longed to be a part of the policy making process. Universities were hotbeds of liberal ideals and protests. Zemstvos were placing pressure on the government for an assembly to reform government policy. Add in a catastrophic war with Japan in 1904, and Russia was ripe with political strife. 31 Figes, Tragedy, 158-160. Figes, Tragedy, 160-162. 33 Simms, Crisis, 397. 32 By 1905, the Russian people felt more comfortable demonstrating for reform; it was imperative to them that their needs be heard. In December the Nicholas was warned of the public outcry and the possibility of a disturbance to the public order. Nicholas was not alarmed, nor even preoccupied by the idea of civil unrest. Whether Nicholas denied the possibility that revolution was on the horizon to himself or that he was completely blind to it remains to be seen, but the Tsar was not prepared for the events of January 1905.34 If he had foreseen the events to come he would have paid greater consideration to the zemstvos’ petition in December 1904 that asked for political reform. While Nicholas did pass the decree, it neglected to mention the allimportant parliamentary body—the one point that was necessary if revolution was to be avoided.35 The 1905 Revolution began with the massacre of one group. This group was a police trade union dreamed up by S.V. Zubatov, loyal to the Tsar and out to rid Russia of revolutionaries. The regime was growing concerned with Zubatov by mid 1903 and the Russian government dismissed him. Father Gapon, one of Zubatov’s supporters, now took leadership and combined a political and religious undertone to the organization. A strike in St. Petersburg in early January 1905 looked to speak to the Tsar and Father Gapon set out to help them. A list of demands was drawn up and a mass demonstration scheduled for 9 January. The government ordered the demonstration to be stopped two days prior to the event, citing “resolute measures” would be taken against any demonstrators. Gapon settled fears, insisting that the marchers would be well received by the Tsar. The myth of the benevolent Tsar lay intact before that 34 35 Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 89. Figes, Tragedy, 173. terrible January morning. As the demonstrators approached the palace gates, the troops attacked. When the massacre was over 200 had been killed and 800 wounded.36 The vision of the benevolent tsar was gone. The idea that the tsar would hear the pleas of the people was gone. Centuries of molding the tsar’s public character into just what the autocrat should be was shattered within hours, eroded away to nothing. Bloody Sunday was over but the anger was just beginning. “The revolution had been truly born, and it had been born in the very core, in the very bowels of the people,” a Bolshevik present at Bloody Sunday recalled.37 Protests did not stop with the fear of military force. Armed and un-armed demonstrations continued by workers, students, and professors across the Russian state.38 The revolution was set in motion and the Russian people demanded change. This would continue throughout 1905 culminating in the October Manifesto.39 The October Manifesto “promised civil liberties and a legislative duma, and decreed the reduction and eventual cancellation of all peasant redemption payments.”40 This was to appease the Russian people and restore order. Nicholas never planned on giving up his autocratic rights; he hated the idea of becoming a constitutional monarch.41 Perhaps if he had embraced this new form of government, he would not have staved off a revolution for a little more than a decade but would have stopped an overthrow of the government from ever happening. Future generations of Romanov’s could have ruled and Nicholas could have passed on the crown to his heir. But Figes, Tragedy, 173-178; Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 89-92. Figes, Tragedy, 178. 38 Verner, Autocracy, 157. 39 Figes, Tragedy, 186-190; Scott J. Seregny, “A Different Type of Peasant Movement: The Peasant Unions in the Russian Revolution of 1905,” in Slavic Review 47, no.1 (Spring, 1988): 56-61. 40 Esther Kingston-Mann, “Lenin and the Challenge of Peasant Militance: Bloody Sunday, 1905 to the Dissolution of the First Duma,” in Russian Review 38, no.4 (October, 1979): 442. 41 Figes, Tragedy, 191-192. 36 37 Nicholas had a very narrow view of how this passing on to his heir should be done. A monarch who shared his power with another body was no monarch at all. But demonstrations and fighting did not stop with the coming of the October Manifesto. A wave of pogroms hit Jews, which was slow to be put down due to the government’s largely anti-Semitic views.42 Nicholas himself was an anti-Semite who blamed the Jews for the January revolution.43 Mutinies also exploded across the state, and, in general, peasant resistance continued.44 Nicholas’ concession was too little too late for the peasants. By November, though, the government saw opportunity to reclaim their power. They were able to suppress street fighting in Moscow and arrested revolutionary leaders from the St. Petersburg Soviet and Moscow Soviet.45 Throughout the 1905 Revolution, Nicholas II tried to please all members of his government that cried for coherence within the government body. Nicholas’ Minister of Agriculture Ermolov, Vladimir Kokvtsev, and General A.A. Kireev all complained about Nicholas’ lack of general direction and coherence within the government. Without this, the government could not properly respond to the revolution. No guiding idea meant confusion among the ministers and many tried to explain their ideas for coherence to Nicholas. But Nicholas tried to please all, creating more confusion, “There was no unified government, no consistency in government policies, because the tsar was refusing to assert control and resolve disagreements. Instead, he tried to be all things to all people.”46 Shlomo Lambroza, “The Tsarist Government and the Pogroms of 1903-06,” in Modern Judaism 7, no.3 (October, 1987): 293. 43 Figes, Tragedy, 197. 44 Kingston-Mann, Lenin, 443-444. 45 Wade, Revolution, 1917, 14. 46 Verner, Autocracy, 168-169. 42 But the tsarist regime was left intact. The groups that had revolted could agree on only one thing, that Nicholas and his government would have to be overthrown. The details on how to do this differed greatly and cohesiveness could not be achieved. The army, for the most part, remained loyal to the tsar and were, therefore, able to help restore order. Also, much of the gentry became reactionary in the peasant violence that ravaged the country. They had money, arms, and men. Without their support, the revolution could not continue. But the main reason why the 1905 Revolution failed was that too many people supported the idea of constitutional monarch. In addition, the general public gained new freedoms. Newspapers now had more freedom, political parties were finally allowed to form, the Duma had been reestablished; and this all meant that the government could never again control the people the way it once did.47 A peasant told Bernard Pares in 1907, “Five years ago there was a belief [in the Tsar] as well as fear. Now the belief is all gone and only the fear remains.”48 The trust was gone, and it would never again return. Now, “whatever chance Russia had of avoiding another revolution rested with the new legislative system.”49 The first Duma clashed terribly with Nicholas and his government, and was dissolved in July 1906. The second Duma lasted under three months before Prime Minister Stolypin ordered Nicholas to dissolve it. The third Duma was made up of pro-government parties, like the Octoberists, Rightists, and Nationalists.50 Stolypin created a set of reforms but these were cut short by his death in 1911 and the outbreak of war. All the time, the working class was feeling more alienated and their grievances were being heard less. Strikes were still 47 Figes, Tragedy, 202-203, 206. Figes, Tragedy, 203. 49 Wade, Revolution, 1917, 14. 50 Figes, Tragedy, 224-225. 48 commonplace. A radicalization of the workers was being to take place after 1912. A new viewpoint was beginning to take shape, one in which if the workers wanted their conditions bettered a change in the political regime was in order.51 Peter Holquist writes of a new “crisis of autocracy” beginning in 1912. Nicholas began to stray away from the reforms of 1905, as well as Stolypin’s reforms. He found complaint with his Council of Ministers, who he felt infringed upon his powers. The tercentenary celebrations in 1913 only added to these growing feelings of the tsar’s. Holquist suggests that this would have a large impact on war policy during World War I.52 The Russian public was becoming more involved in the events surrounding the impending war in Europe. Patriotism was spreading, and by 1913 a war would be “joyfully welcomed and it will raise the government’s prestige.”53 Public opinion was now something that could not be ignored, but the Tsar was slow to come around to the sentiment of his people. Nicholas II would be pushed into war due to the circumstance on the home front. He was afraid that if he were defeated in battle revolution would occur. But the fear of revolution if he did not go to war was greater and Nicholas relinquished. Russia joined the war in August 1914, expecting a short war with minimal expenditures of food, ammunitions, and lives.54 It was evident even before the war began that the entire autocratic regime was in trouble. Leon Trotsky shared in this viewpoint. He wrote, “War often brings about revolution. This is not so much because the war was unsuccessful in a state sense, as because the war did not satisfy 51 Wade, Revolution, 1917, 15-16. Peter Holquist, Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia’s Continuum of Crisis, 1914-1921 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2002), 13. 53 Figes, Tragedy, 248. 54 Figes, Tragedy, 250-251. 52 all expectations.”55 For Trotsky, revolution was the only answer to Russia’s problems. The breakdown of the autocracy was inevitable and this would in turn release “the revolutionary energy of the people.”56 And at the point where Russia was at, reform of the autocratic regime would not have been enough. Revolution was logical. If the autocrat had to worry about overthrow, even a war could not save him in the larger picture. Russian nationalism may have bonded the Tsar to his people, but this was only brief. A sense of national self would only help the Russian people to find the unity that they lacked in the 1905 Revolution. Perhaps this is why Nicholas began to grasp for powers that had been taken away and cling to them. He could feel that they were slipping away, and this time it would not be brief but for good. For however much he said he loved his people,57 he loved his power. If the reverse were true, he would have given up some of that power to improve the lives of his beloved people. Not even two months into the war, the Empress Alexandra was asking her husband, “This miserable war, when will it end.”58 “By the beginning of 1915, the results were terrible: 1.2 million killed, wounded, missing, or prisoners. New troops had to be raised; seven hundred thousand men were recruited. Russia was beginning to run short of [material], especially ammunition.”59 But the Russian people remained loyal and patriotic, not knowing the full extent of problems on the front lines. This would soon change when Germany gained momentum and controlled Russian land. The people turned spiteful toward their government, and “hostility 55 Ian D. Thatcher, Leon Trotsky and World War I, August 1914-February 1917 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 3-4. 56 Thatcher, Trotsky, 9 and then 5. 57 Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 91. 58 Tsar Nicholas II & Empress Alexandra Romanov, The Complete Wartime Correspondence of Tsar Nicholas II and Empress Alexandra, April 1914-March 1917, ed. Joseph T. Fuhrman (Westport, Connecticut: Green wood Press, 1999), 25. 59 Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 174. turned first of all to the empress, the German.”60 From then on, the loyalty of the Russian people began to fade and the patriotic fervor that had engulfed society was turning into a different kind of zeal, one directed against the Tsar and his government. Just as the 1905 government had no coherence, the army remained divided between three separate entities: “the War Ministry, Supreme Headquarters, and the Front commands. Each pursued its own particular ends, so that no clear plan emerged.” This was to be one of their greatest weaknesses.61 Without a clear structure the Russian government had no possibility of winning. No plan meant wasting resources and lives. 1915 would bring a great many changes for Russia and the war would have a direct affect on this. Due to falling public morale and defeats on the battlefield Nicholas would shift around members of his government and dismiss others altogether. He removed his minister of war and brought in General Polivanov to replace him. This was all to garner public support for the war and appease public opinion.62 The Russian state, also in 1915, changed the structure of buying grain. The minister of agriculture, which had previously purchased grain for the army, now also did so for the entire Russian population.63 And soon after, Nicholas finally gave into the temptation he felt to lead the troops. This was seen by many to have disastrous consequences in the future.64 The voice of opposition against the Tsar was growing more and more, and now included more than half of the Duma. The Progressive Bloc called for a “nine-point program” that had the Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 174-175. Figes, Tragedy, 258. 62 Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 175. 63 Holquist, Making War, 27. 64 Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 178. 60 61 “confidence of the nation.”65 And out on the front lines the soldiers were demoralized. Food and ammunition shortages, and defeats contributed to a lackluster group of men.66 Now, Nicholas began the final assault on his own autocratic rule. He dissolved the Duma for a final time, taking back his autocratic power but also leaving him with little popularity among his people. Nicholas dismissed General Polivanov in March 1916. This hurt Nicholas as well. Polivanov was “more than any other man responsible for the rebuilding of the Russian army after the terrible losses of the Great Retreat” and also contributed to the improved morale of the troops on the front lines.67 Shortages were growing in “food, fuel and basic household goods, the rapid inflation of prices, the breakdown of transport, the widespread corruption of the government and its military suppliers, and the steep increase in crime and social disorder—all these combined with the endless slaughter of the war to create a growing sense of panic and hysteria.” So that by mid 1916 “the word ‘revolution’ was on everybody’s lips.”68 Nicholas II would be forced to abdicate on March 2, 1917 after a month of fighting to maintain control over a riotous population. He and his family would eventually be killed for their wrongdoings to the state. He was at the head a fledgling government, sitting on the precipice of something new. “The autocracy was to stolid to recognize that it jeopardized itself by not keeping pace” with the changes of the country, the push toward modernity.69 Nicholas and his family would have to pay the ultimate price for their failure to modernize, and his innocent children would bare this burden as well. Carrère d’Encausse, Nicholas II, 177. Holquist, Making War, 26-28; Figes, Tragedy, 262-270 67 Figes, Tragedy, 275-279. 68 Figes, Tragedy, 282-283 for both quotes. 69 Lambroza, Pogroms, 291. 65 66 The famine crisis politicized the Russian people, the 1905 Revolution brought anger to them, and the First World War became the final catalyst to revolution as the walls of autocracy began to crumble from the frustration with the ruling government. Nicholas could perhaps have stopped the revolution if he had given up some of the autocratic ways of his forefathers, but the stubborn Nicholas wanted to carry on in the old autocratic ways. But the archaic system crumbled under its own weight. It is possible that the revolution could have occurred without one of the above-mentioned events. The revolution may simply have happened at a different time, different place. The revolution needed Nicholas; he was the current running through all the events. He was a victim of time and circumstance, along with his own shortcomings. It came down to a modernizing Russia looking toward the future and a stubborn autocrat looking backward, toward the past.