Community Engagement with Archaeology in the

advertisement

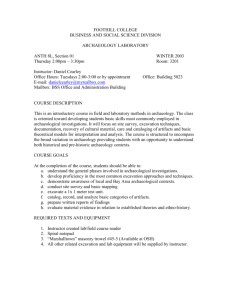

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT WITH ARCHAEOLOGY IN THE SOUTH DORSET RIDGEWAY LANDSCAPE PARTNERSHIP AREA: A PRELIMINARY REVIEW DRAFT REPORT A report prepared for: Dorset Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Partnership PO Box 7318 Dorchester Dorset DT1 9FD By Andrew Fitzpatrick Heritage 102 Boscombe Grove Road Bournemouth Dorset BH 4PG Report Reference: AFH Report 13/02.01 January 2013 © A.P. Fitzpatrick 2013 Community Engagement with Archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership Area: a preliminary review DRAFT REPORT 1 Introduction 1.1 This report has been prepared to provide a preliminary review of current and possible future models of community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership Area (hereafter SDRLP). 1.2 A brief for this report was agreed with the Development Officer before work commenced. 1.3 The report considers the role that the past plays in perceptions of the SDLRP area and the level of interest in engaging with the past, and archaeology in particular. In order to provide a focus for further engagement, some key topics for the Ridgeway contained in the South West Archaeological Research Framework (2008) and which community groups could work on are identified. The archaeology groups and organisations currently active in the SDRLP area are then reviewed as are current models of community archaeology across the UK, and how community engagement with archaeology has been attempted in a range of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and National Parks. In the light of this review suggestions are made about the types of activities and projects that might be considered suitable for community engagement in the SDRPL area and the issues and resource implications for the SDRLP are identified. The report concludes with some recommendations. 2 The role that the past plays in public perceptions of the SDRLP area 2.1 The past plays an important role in shaping perceptions of the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership Area (hereafter ‘the Ridgeway’). The numerous well-preserved burial mounds that stud the Ridgeway and the presence of mighty hillforts are key elements in giving the landscape a time depth and help shape its individual character. 2.2 The Audience Development Plan for the Ridgeway reports that in the data collected through the 2012 Citizen Panel, the natural environment was considered to be the most important factor contributing to a distinct local character (Resources for Change 2012, section 2.2.2). The second most important factor was the historic environment, which is defined here as comprising the Citizen Panel survey categories of town/village architecture, old buildings, hedgerows, and prehistoric earthworks. 3 The level of interest amongst the public in engaging with the past, and with archaeology in particular, in SDRLP 3.1 In that survey 87% of people said that they would like to learn more about heritage (Resources for Change 2012, section 4.3.2) and 31% would like to become involved in heritage volunteering. Heritage is therefore an important concern amongst visitors to the Ridgeway. 1 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review 3.2 What is perceived as having heritage value is not well-defined. Broad statements about ceremonial landscapes, while evocative, need to be developed and defined more closely to enable activities that engage with specific audiences to be identified and developed. 4 Topics in the South West Archaeological Research Framework that could be undertaken by community archaeology groups in the SDRLP area 4.1 The South West Archaeological Research Framework is one of a series of Regional Frameworks sponsored by English Heritage. It was produced by volunteers from all sectors of the archaeological community including local societies. 4.2 The Framework provides i) a review of what is currently known (the Resource Assessment), ii) the priorities for research (the Research Agenda) and iii) how those priorities might be implemented (the Research Strategy). The Resource Assessment and the Research Agenda were published in 2008 (Webster 2008). The draft Research Strategy was published in 2011 and consultation on it has closed. 4.3 There are 64 Research Aims, many of which are subdivided so that the actual total of Aims is nearer to 400. Most of these aims are either period based (e.g. ‘what effect did the first Neolithic farming have on the landscape?’) or method based (e.g. ‘the methods used to collect evidence for Neolithic farming and prehistoric farming in general, need to adopt the following new techniques’). Relatively few Aims are geographically specific and this is the case for the South Dorset Ridgeway. 4.4 It should be noted that an important new source of evidence was not available when the Research Framework was prepared. The survey of the Ridgeway by the English Heritage National Mapping Programme was undertaken in 2008-10 and it identified many new sites. 4.5 The large number of Research Aims identified in the Research Agenda means that in practice it is possible to match most possible projects with one or more Aims. However, for the South Dorset Ridgeway three subjects that are key to the ways in which the modern landscape is currently understood and valued may be identified. The first two relate to the well known prehistoric monuments but the third relates to an often overlooked period that laid the foundations for the contemporary landscape; 1. The large number of well preserved prehistoric burial mounds. These were often sited to be prominent features in the contemporary landscape and that remains the case today. A few of these mounds are Neolithic in date (Late Stone Age, c. 4000-2000 BC) but the great majority are Bronze Age (c. 2000-700 BC). 2. The Iron Age hillforts. Dorset as a whole has a large number of hillforts and there are several well-preserved examples in the Ridgeway AONB. These forts date to between 700 BC and the Roman Conquest led by Vespasian in AD 43. The hillfort at Maiden Castle is one of the most famous prehistoric monuments in Britain. 3. The development of the medieval landscape. The medieval landscape provides the base map for the contemporary landscape. Features that are thought to be modern can be surprisingly old, up to 1,000 years. The settlement pattern of villages and farms was established early in the medieval period and the patterns 2 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review of medieval land use meant that many Bronze Age barrows and Iron Age forts were incorporated into it and preserved in areas of pasture. 4.6 Many remains of these sites survive as well-preserved earthworks but many have also been destroyed and are known only though buried archaeological evidence. For the medieval period some buildings still stand and there is also documentary evidence. 4.7 A number of Research Aims can be matched to these three key subjects; 1 For the prehistoric burial mounds Research Aim 54 is to ‘widen our understanding of monumentality in the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age.’ That is to say, why the monuments were built where they were, why in that shape, and what they stood in relation to. This Aim is fundamental to the shaping of the Ridgeway. 2 Some fundamental questions remain to be answered about the hillforts. It is not known if all of the hillforts were occupied permanently and continuously though their life. Or did most of the population lived in small farms and only came to the forts in times of crisis? The emphasis is as much on the systems that supported the hillforts, including new permanent farms and the development of field systems, as it is on the forts (Research Aims 21 and 41). 3 For the medieval period the Research Aims also include fundamental questions that link directly to the contemporary landscape of the Ridgeway. The Aims for ‘Early medieval landscapes and territories’ includes topics such as ‘the origins of the parish’ (Research Aim 31), ‘the location and identification of medieval religious buildings, monuments and landscapes’ (Research Aim 32) and ‘to widen our understanding of the origins of villages’ (Research Aim 33). 5 Archaeology groups and organisations active in the SDRLP area 5.1 While many people visit archaeological sites occasionally, the next steps in engaging more actively are typically to visit museums or to join a local archaeology or history society. This section reviews the existing opportunities to become involved in archaeology in and around the Ridgeway. The important role of Dorset’s museums is acknowledged but for the purposes of this report attention is focussed on archaeology societies and other groups. As many visitors to the Ridgeway come from elsewhere in Dorset this information is reviewed at a county scale. Societies 5.2 By far and away the largest amateur society active in the area is the Dorset Archaeology and Natural History Society with a membership of c. 2000. This is a county-wide society whose interests embrace a range of subjects across the historic and natural environments and beyond. The society runs the Dorset County Museum in Dorchester and has a professional staff. Some of members of the society live outside the county but have a strong interest in it, and there are also some institutional members. 5.3 The other archaeology societies in Dorset do no not cover such a wide range of subjects, are smaller and are based in towns (Shaftesbury, Weymouth, Wareham, 3 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review Wimborne and Bournemouth) (Appendix 1). The principal activity of these societies is the organisation of lectures and visits (section 6.6 below) and to an extent these activities are also provided by the Friends groups of local museums particularly in the smaller towns with archaeology collections (Appendix 2). A small independent group is run in Bridport by a professional archaeologist (Appendix 1). 5.4 Marine and maritime archaeology is a popular subject and groups with a specialist interest in these field are the Dorset Coast Forum Archaeology Group (Weymouth), the Poole Maritime Trust, and the Weymouth LUNAR (Land and Underwater Archaeological Research) Society. 5.5 Historic Buildings are often a concern of the urban Civic Societies who often have access to meetings organised by the Dorset Building Group. For more recent periods there is also a considerable overlap with the interests of local history societies. 5.6 The Council for British Archaeology is a national umbrella organisation which has regional groups. The SDRLP and Dorset are in the Wessex Region. A significant proportion of the members of the regional groups are members of local societies. 5.7 The Portable Antiquities Scheme operates in England and Wales to promote the reporting of archaeological finds. It is organised by the British Museum on behalf of the Department of Culture Media and Sport. There is a Finds Liaison Officer for each county in England and the Dorset Officer is located with the County Council in Dorchester. In addition Dorset County Council operates a Metal Detectorists Liaison Scheme. It should be noted that detectorists often visit sites beyond their home county. 5.8 The Portable Antiquities Scheme has worked closely with metal detector users and the Liaison Officers regularly attend meetings of metal detecting clubs (Appendix 3), history fairs and other related events. As such the Scheme represents the first point of contact with archaeology and archaeologists for many people. Fieldwork 5.9 Excavation is still the dominant public perception of archaeology even though it forms only a small proportion of all archaeological works undertaken in the United Kingdom. 5.10 Most archaeological work in Dorset is undertaken by commercial practices as part of the planning process. The short lead-in time for these projects combined with budgetary constraints result in it being unusual for volunteers to be to able to participate in these projects. Conservation management projects can involve field surveys and these are usually also undertaken by commercial practices. The location and timing of these projects is dictated by the developer and/or land manager. 5.11 Research excavations are rare and in recent years most of these have been undertaken by Bournemouth University, though several other universities have undertaken work in the last 20 years. These are usually quite small and they combine the research interests of the staff with the need to provide fieldwork experience for students as a course requirement. The current ‘Durotriges Big Dig!’ at Winterbourne Kingston, north of Bere Regis is unusual in being planned on a larger scale as summer school, and is intended primarily for undergraduate students. In 2013 this project will run for 4 weeks (3 - 28 June, Monday-Friday, 9am - 5pm). 4 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review 5.12 The National Trust archaeology team undertakes small pieces of fieldwork on its properties and there opportunities for volunteers to participate in this. Training excavations run by professional organisations are rare, the last being on Cranborne Chase which was organised by Wessex Archaeology and which ended in 2009. 5.13 Two amateur local societies in Dorset regularly undertake fieldwork; the East Dorset Antiquarian Society which is based in Wimborne has traditionally worked on Cranborne Chase on a farm owned by one of its members. The Wareham and District Archaeological Society undertook large excavations in the 1990s in a development context and occasionally undertakes small pieces of development work as well as small research excavations. Much of the fieldwork of these two societies is due to the presence of a few highly able and motivated individuals. 5.14 Archaeological fieldwork in Dorset is therefore largely undertaken in response to developments and where research or management works are planned it is in the context of the programme of the sponsoring body. There is no co-ordinated programme of work across the county as whole or in the area of the SDRLP. 5.15 The Archaeology Committee of the Dorset Archaeology and Natural History Society plays a co-ordinating role in the reporting of all fieldwork and in responding to public consultations that involve archaeological matters. 6 Current models of community archaeology practised in the United Kingdom. 6.1 This information about Dorset should be seen in a wider context of public engagement with archaeology in the United Kingdom. The term ‘community archaeology’ is widely used to refer to the participation of ‘non-professional’ archaeologists and volunteers in archaeological projects. The origins of the term lie in the development of archaeology as a professional discipline during the later 20th century. The professionalisation of the discipline led to it taking on the leading role previously played by many voluntary bodies, notably county archaeology societies, in the 19th and earlier 20th centuries. 6.2 One aspect of this professionalisation was the perspective that the conservation and management of the historic environment, including archaeology, was on behalf of the community. This view echoes ones held in the wider conservation and environmental movements. While the concept of community archaeology places a greater emphasis on active participation in the practice of archaeology by the public, it still embodies a disjunction between how professionals and amateurs engage with the past. It is an issue than can cause many difficulties in engaging the public with archaeology. 6.3 A survey of community archaeology across the United Kingdom was recently undertaken by the organisation The Council for British Archaeology. The Council speaks on behalf o archaeology generally and the amateur sector in particular. The results of the survey were published in 2010 and are based on the most extensive consultation with amateur archaeological societies undertaken in the UK. The survey included historical and other societies which undertake archaeology even if their name might not immediately suggest that they do (Thomas 2010). For convenience these groups are all called ‘societies’ here. 6.4 The survey represents the first ‘bottom up’ survey of public archaeology and it provides a striking contrast with the ‘top down’ views contained in a report on ‘Participating in the Past’ that was published by a Working Party of the Council for 5 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review British Archaeology as recently as 2003 (Farley 2003). The 2010 report provided for the first time a research-based assessment what amateur societies in the United Kingdom currently do and what they would like to do. 6.5 Amongst other things, the report analysed the types of activities the societies were involved. The principle conclusions of the survey are summarised below but it is important to note that the survey recorded participating in activities, not necessarily organising them. The subjects of the activity can also vary widely according to chronological period and geographical location. Activities undertaken 6.6 The activity most commonly undertaken by archaeology societies was organising talks. This was done by 92% of the respondents (Table 1). The next most popular activity was organising visits, typically to archaeological sites and/or museums. This was followed by taking a table at history fairs or similar, recording through photography, archival research, and organising exhibitions. 6.7 Forty-three percent (43%) of the respondents had participated in archaeological fieldwork. Fieldwalking (the systematic collection of artefacts from the surface of ploughed fields) was the most frequent, closely followed by excavation. The recording of historic buildings was also popular. Excavation Visits Participating at History fairs Photographic Recording Archival Research Organising Exhibitions Fieldwalking Excavation Recording Buildings 24% 80% 62% 58% 57% 52% 43% 41% 38% Table 1: Activities undertaken by local archaeology societies. Source: Thomas 2010. 6.8 These figures demonstrate that talks and visits were far and away the most common activities. Photographic and archival research were more popular than fieldwork in which less than half of the societies participated. Although the survey did not collect data on this point, it is clear that many societies participated in fieldwork organised by third parties. This seems to have been particularly true for excavations. Overall, there was little difference in the popularity of surveys, excavations and recording buildings. Activities societies would like to become involved with 6.9 The Council for British Archaeology survey also considered what societies would like to do. There was a clear preference for being involved in survey work. The most popular choices were: Landscape surveys Geophysical surveys Topographic survey Fieldwalking Building recording Excavation 34% 31% 28% 28% 27% 24% 6 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review Table 2: Activities that local archaeology societies in the UK would like to become involved in. Source: Thomas 2010. 6.10 The main barriers to broadening the range of activities that the societies undertake were lack of training and access to equipment. In the case of excavation this is now seen, correctly, as an activity which requires a high level of specialist input in the reporting stage. It is also thought that it is difficult for amateur societies to access this specialist input. These concerns deter many societies from undertaking excavations. 6.11 Returning to the Ridgeway, it should be noted while the Audience Development Report states that there was a clear preference for people to learn more about the heritage of the Ridgeway through active learning of a ‘hands on’ nature, for example community archaeological digs (Resources for Change 2012, section 5.4, objective 5), the data presented in Chart 24 of the report indicates that the main preferences for learning more were through guided walks or talks, information leaflets, and exploring on ones own. This is consistent with the types of activities preferred by local archaeological societies. 7 Community archaeology in AONBs and National Parks 7.1 Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and National Parks share common concerns in conservation and encouraging access, and the share many problems. In order to assess what types of community archaeology has been undertaken recently in situations comparable to that of the SDRLP, a rapid web review was undertaken of the activities undertaken in a range of National Parks and AONBs. Two widely separated regions were chosen, southern England and north-east England. The sites of five National Parks and eight AONBS were consulted (Appendix 4). The South Dorset Ridgeway Heritage Project is considered separately below in section 8.6. 7.2 This rapid review demonstrated a wide variation in the activities promoted by the authorities. While archaeology and the historic environment was widely acknowledged as playing an important role in creating what is special about the areas, the emphasis placed on archaeology and heritage as individual subjects was typically on conservation and management. 7.3 In one case (the Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Downs AONB) archaeology had been used systematically as part of a Historic Landscape Characterisation project. Here archaeological sites and features were assessed to see how they contributed to the development of the whole landscape through time, and this time depth was emphasised not just the special or unique sites. This work was undertaken by professionals and was envisaged as a management tool although some selfguided trails were prepared. Exmoor National Park has produced its own Historic Environment Research Framework, while this is a scholarly and technical document, it also emphasises that better understanding of the resource will lead to improved management systems and conservation. The Exmoor Framework refers to the South West Archaeological Framework. These examples reflect the public emphasis on conservation and management, and research. 7.4 In general, relatively few opportunities to engage with archaeology or to participate in it were offered by the authorities. These were not necessarily all organised by the authorities and some were promoted as part of partnership working. A good example of this is a long running project in the Northumberland National Park where the Breamish Valley Project is jointly run by the University of Durham, a local society (the 7 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review Northumbrian Archaeology Group) and the National Park. This is a legacy project from an earlier successful project on Hillfort Heritage (partly HLF and European funded) that secured access to some previously inaccessible hillforts, self-guided trail leaflets and interpretation panels that link many of the most important sites in a coherent way, and education resources. 7.5 The most common activity in which archaeology was promoted was in guided walks in which it was one of several subjects treated in multi-disciplinary approach. There were also a few self-guided walks. Specific events were sometimes offered as part of the annual Festival of British Archaeology which is organised by the Council for British Archaeology and which runs for one month each summer. Activities included offered here included site tours (sometimes with the opportunity to visit research excavations but not participate in them), guided walks, and children’s activities facilitated by story tellers or re-enactors. 7.6 The North Wessex Downs AONB promoted woodland archaeology, the study of what is hidden amongst the woods, as a community survey project. Occasionally surveys of specific types of modern sites are undertaken, such as pill boxes and in some cases, notably in the New Forest National Park, small community excavations were organised as part of planning applications. The excavations were managed by professional practices who also undertook the reporting necessary for the planning application. The New Forest also organised a coastal survey with recreational divers, again working under professional supervision. 7.7 The greatest number of opportunities to engage with archaeology and the opportunities promoted most actively were in HLF-funded projects. A very successful example of this is the ‘Altogether Archaeology’ project organised by the North Pennines AONB where an HLF-funded pilot project in 2010-11 led to a successful bid for 3-year project for 2012-15. Although not included in the survey, the Peak District National Park has also undertaken extensive community work that has won national recognition. A common factor in the success is that both authorities have archaeological officers who manage and facilitate the work but do not necessarily undertake the day to day running of it. 7.8 The North Pennines projects are based on modules. These are mostly site specific pieces of fieldwork which professional archaeologists are commissioned to lead and undertake the reporting. The sites in the modules are distributed across the AONB and from different periods with the intent of being able to offer something for everyone. 8 The objectives and models of community engagement already practised or planned in the SDRLP area 8.1 From this brief review it can be seen that the Ridgeway is typical of most AONBs and National Parks in that little community archaeology is currently done. The most frequent activity in the area is attending the lectures organised by local societies and museums. 8.2 The majority of archaeological fieldwork in the SDRLP area is undertaken by commercial practices and there are only very limited opportunities for amateurs to participate. 8 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review 8.3 A small number of fieldwork opportunities are provided by the National Trust (for example their recent excavations at Golden Cap) or within the research projects undertaken by Bournemouth University. Small amounts of fieldwork are also undertaken by local societies based in Wareham and Wimborne and until 2010 trial excavations on the route of Roman roads were undertaken by the small and informal Bridport based Dorset Roman Roads Group. A rare example of conservation management (not just in the SDRLP) is the restoration of the Osmington White Horse, the improved access to it, and the agreement of a management plan. The work was initiated and undertaken by the community aided by good professional support. 8.4 Other opportunities are provided by the National Trust, events at English Heritage guardianship sites, and by the staff of Historic Environment Team of Dorset County Council. The Dorset Archaeology Committee organises an extensive annual programme of guided walks across the county (Dorset Archaeological Days). 8.5 However, the location, nature and timing of these activities and events are not coordinated. 8.6 A good and successful recent example of what can be achieved in a community archaeology project is the South Dorset Ridgeway Heritage Project which was run by the Dorset AONB in 2008-11 and funded by HLF and Natural England. As summarised in the end of project report and evaluation (Dorset AONB 2011), the project had four aims; 8.6.1 The first, ‘Celebration’ promoted the appreciation of the archaeological heritage of the Ridgeway though; art exhibitions and events, a new guidebook, historic reenactment events, talks and lectures, storytelling, guided walks, and an event; the 2010 South Dorset Ridgeway Festival. 8.6.2 The second strand promoted ‘Learning’ by enabling schools to use the Ridgeway in teaching the National Curriculum. This was done by providing teaching resource boxes, learning resources, support for school trips, outreach sessions and teacher training. 8.6.3 The third strand ‘Research’ involved survey and protection of monuments. This was delivered though surveys carried out by Bournemouth University and volunteers, the publication of the results, and collecting oral history. 8.6.4 The fourth strand, ‘Access’ enabled better access by publishing circular works, two audio trails, palm pilot guided trails, a new website, new waymarks along the routes of the trails, and the research and publication of village maps. 8.6.5 This range of activities represents what might be expected in a good recent community archaeology project. They also demonstrate that it is possible to approach audience development without undertaking much archaeological fieldwork. 8.6.6 The only observation that need be made here is that the project provided relatively few opportunities for the range of fieldwork activities that the Council for British Archaeology survey (which had not been undertaken when the project was planned) indicates that local societies would like to participate in. 9 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review 9 The types of activities and Research Projects that might be considered suitable for community engagement in the SDRPL area 9.1 It is clear that there is potential to improve the first steps in enabling the public to engage with archaeology by providing more walks, talks and events and this is not considered further here. Instead, having briefly reviewed the types of community archaeology generally undertaken and in AONBs and National Parks in particular it is possible to return to the three subjects that were identified in Section 4 above as key to the ways in which the modern landscape is currently understood and valued. Those subjects were prehistoric burial mounds, prehistoric hillforts, and medieval villages and their landscapes. The remains of these monuments are widely and readily visible. 9.2 The Research Aims in the South West Archaeological Research Framework are specific to chronological periods but they are linked by a desire to improve the understanding of why certain sites were created where they were, and how they related to other contemporary sites. For example, in the Bronze Age why was a particular place chosen to build burial mounds, and where had the people who were buried in them lived? 9.3 These questions are essentially about the importance of places and as such they are well suited to projects for community engagement as they focus as much on a sense of place rather than a detailed technical understanding of the archaeological evidence for a given period. The exact details of these questions (and of course others) can be matched to particular groups but at a broad level the questions have a strong correlation with the topics considered in the Audience Development Plan (Resources for Change 2012). The answers can be developed over several stages of work which will allow participants to develop their engagement to their own levels. 9.4 The questions can be addressed initially by trying to understand the landscape around individual sites or group of sites. This could, for example, involve visiting the site, compiling and reviewing what evidence there is for those sites and others in the neighbourhood (e.g. archaeological remains, buildings or documentary records), considering the views from and the view to the sites, the location of suitable agricultural land, and , where appropriate, their suitability as defensive locations. 9.5 The training requirements for these types of activity are mainly clear briefings which can be delivered in workshop format and access to (and understanding of) mapping. They do not require specialist equipment or detailed specialist or technical knowledge but the individual studies can contribute to a bigger picture. 9.6 The results of this work might include photomontages/panoramas, maps of potential land use and catchment areas, village and parish maps and accompanying reports. Although these outputs are quite simple it is also possible to use them in more complex ways, for example by undertaking viewshed analyses of barrows or forts. Irrespective of the types of analysis undertaken, the result of such studies should be readily intelligible to a wide audience as they already have some understanding of the subject matter and value its contribution to making the Ridgeway. 9.7 This work might then be developed into a second stage that could involve more systematic and detailed surveys such as topographic survey, geophysical surveys, standing building surveys and documentary surveys. Again these studies can be undertaken as individual projects that can contribute to a bigger picture about the Ridgeway. It would be possible to develop further stages of work. These might for 10 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review example involve looking at finds from old excavations or organising new small-scale excavations. 9.8 As stated above projects can be matched to groups and locations when the exact details can be established. It should be noted, however, that all Scheduled Monuments, which are protected by law, require permission in the form of Scheduled Monument Clearance not only for excavation but also geophysical survey. This clearance is now obtained through English Heritage. Most of the prehistoric barrows and all of the hillforts in the SDRLP are Scheduled Monuments. 10 The issues and resource implications for the SDRLP of community engagement with archaeology in SDRLP area 10.1 Successful community engagement with archaeology requires effective partnership working. As shown in sections 6 and 7 above, another prerequisite is adequately resourced support from heritage professionals. This is needed to provide the correct preliminary information, to deliver the necessary training at the appropriate time and to provide support and expertise. Ideally this would also involve securing the necessary permissions from landowners and farmers for access. 10.2 However, much of the care and support that should be offered to groups and individuals does not require specialist heritage knowledge. 10.3 The SDRLP should consider whether to develop existing audiences and match a choice of possible projects to them, or whether to develop projects and then try and attract audiences to them. The two approaches are not mutually exclusive. 10.4 Taking the first approach will take longer and will require the establishment of programmes of talks, walks, trails and events. The survey by the Council for British Archaeology (Thomas 2010) clearly demonstrates that at a national level these are the most popular ways of engaging with archaeology and the evidence from the South Dorset Ridgeway Heritage Project is consistent with this. 10.6 The second is in some ways easier to achieve but will very probably engage a smaller audience, as is demonstrated by the evaluation of the South Dorset Ridgeway Heritage Project. 10.7 In either situation the longer-term impact and sustainability of any work after projectfunding has ended should be considered. 11 Recommendations 11.1 This report has summarised the current provision of community archaeology in the SDRLP and placed in a wider context. Drawing on the recent South West Archaeological Research Framework some simple but bold research questions that can be addressed effectively by community archaeology have been identified. The overriding emphasis on a sense of place means that these questions may be addressed by many groups working independently or in partnership. Just as importantly the importance of the research should be readily understood by a wider audience who appreciate the contribution that the archaeological remains make to the Ridgeway landscape. 11 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review 11.2 The programme is already set for the imminent Round 2 HLF submission but at the delivery stage the SDRLP may wish to review the opportunities for community engagement with archaeology that will be offered by Partners. This review might include; The strengths, weaknesses and opportunities of this provision should be assessed against the known preferences for community archaeology activities. Attention given to how existing archaeology activities might be coordinated, planned and publicised to potential SDRLP audiences and participants more effectively. The opportunities for integrating archaeology and heritage more generally with activities delivered for other disciplines (e.g. ecology) should be reviewed. If closer interdisciplinary working is considered possible, the training requirements necessary to achieve this should be defined. If members of the SDRLP and stakeholders are willing and able to participate in developing community engagement with archaeology. Their capacity to participate and the constraints on that should be clearly established to ensure a shared understanding. Existing groups of volunteers within SDRLP should be asked if they would like to develop their own local archaeology projects along the lines of those set out in sections 7-9 above with professional support. This may have cost implications. Feedback from people interested in participating in community archaeology activities should be gathered. The current uses of heritage and archaeology are of limited use in developing bespoke activities. Feedback will provide greater clarity about what really interests people. This feedback could be gathered as part of a public meeting that showcases the archaeology and environment of the Ridgeway. It is recognised that the programme for the first two years of the Landscape Partnership is set but feedback could be gathered to assist in developing the detailed programmes for Years 3-5. 12 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review References Dorset Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty 2011, South Dorset Ridgeway Heritage Project 2008-2011. Final report and evaluation, Dorchester, Dorset Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty: http://www.dorsetaonb.org.uk/assets/downloads/South_Dorset_Ridgeway/SDRHP_Fi nal_report.pdf Farley, M. (ed.), 2003, Participating in the Past. The results of an investigation by a Council for British Archaeology Working Party chaired by Mike Farley, York, Council for British Archaeology: http://www.archaeologyuk.org/participation/ Resources for Change 2012, South Dorset Ridgeway Audience Development Plan, Llanymynech, Unpublished report by Resources for Change for Dorset Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Thomas, S., 2010, Community Archaeology in the UK recent findings, York, Council for British Archaeology: http://www.archaeologyuk.org/sites/www.britarch.ac.uk/files/nodefiles/CBA%20Community%20Report%202010.pdf Webster, C.J. (ed.), 2008, The Archaeology of South West England. South West Archaeological Research Framework, Resource Assessment and Resource Agenda, Taunton, Somerset County Council: http://www1.somerset.gov.uk/archives/hes/downloads/swarfweb.pdf 13 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review Appendix 1 Amateur Societies in Dorset either devoted to or with an interest in archaeology Avon Valley Archaeological Society Bournemouth Local Studies Group, Bournemouth Bournemouth Natural Science Society, Bournemouth Bridport History Society Christchurch Antiquarians Christchurch History Society Dorchester Association Dorset Coast Forum Archaeology Group, Weymouth Dorset Building Group, Swanage Dorset Industrial Archaeology Society, Dorchester Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society, Dorchester Dorset Roman Roads Group, Bridport East Dorset Antiquarian Society, Wimborne Gillingham Local History Society Langton Matravers Local History and Preservation Society Poole Maritime Trust, Poole Shaftesbury and District Archaeological Society, Shaftesbury South Wessex Archaeological Association, Bournemouth Wareham and District Archaeology and Local History, Wareham Weymouth LUNAR (Land and Underwater Archaeological Research) Society, Weymouth Xcavate!, Bridport Appendix 2 Museums in Dorset with archaeology collections Beaminster Museum Blandford Town Museum Bournemouth Natural Science Society, Bournemouth Bridport Museum Core Castle Museum Dorset County Museum (Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society) Gillingham Museum Gold Hill Museum and Garden, Shaftesbury Langton Matravers Parish Museum Lyme Regis Museum Poole Museum Priest’s House Museum and Garden, Wimborne Red House Museum and Gardens, Christchurch (run by Hampshire Museums Service) Russell-Cotes Art Gallery and Museum, Bournemouth Sherborne Museum Swanage Museum and heritage Centre Wareham Town Museum 14 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review Appendix 3 Metal Detector Clubs in Dorset Bournemouth Detecting Club, Bournemouth Dorset Detector Group, Bournemouth Stour Valley Search and Recovery Club, Wimborne Weymouth and Portland metal Detecting Club, Weymouth In addition metal detector users may be members of the Federation of Independent Detectorists. Appendix 4 Websites of Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty and National Parks consulted National Parks Dartmoor National Park Exmoor National Park New Forest National Park Northumberland National Park South Downs National Park Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty Cranborne Chase and West Wiltshire Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Dorset Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty East Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Mendip Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Northumberland Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty North Pennine Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Quantock Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. 15 Community engagement with archaeology in the South Dorset Ridgeway Landscape Partnership area: a preliminary review