3_sc_c_1_vidic, 188 kB

advertisement

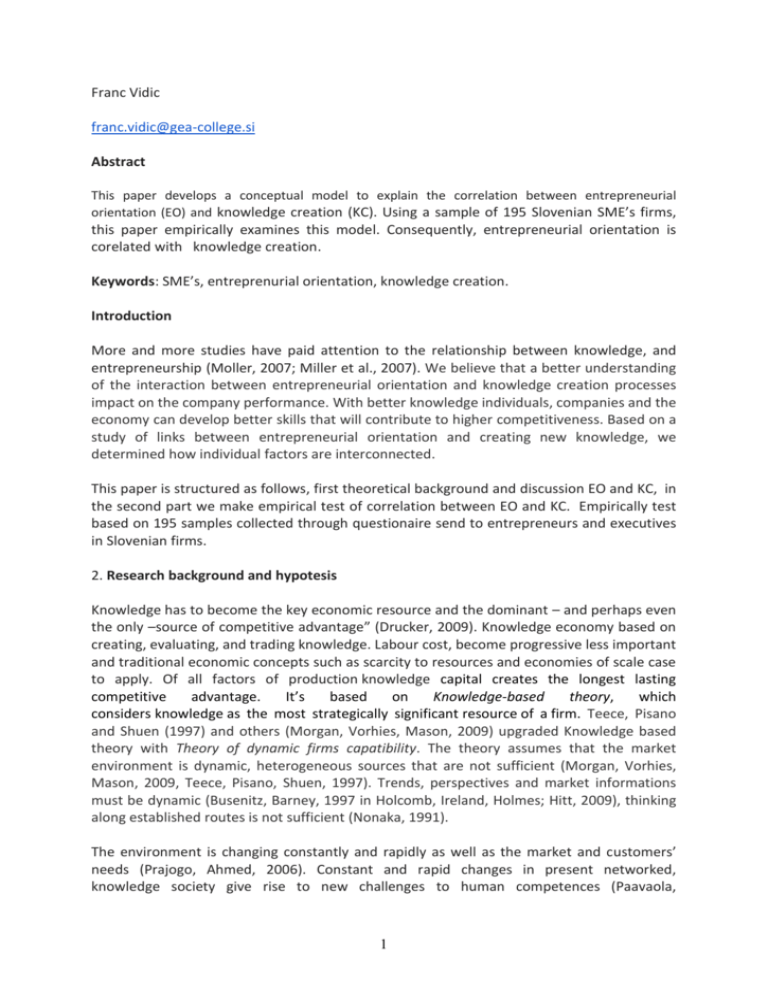

Franc Vidic franc.vidic@gea-college.si Abstract This paper develops a conceptual model to explain the correlation between entrepreneurial orientation (EO) and knowledge creation (KC). Using a sample of 195 Slovenian SME’s firms, this paper empirically examines this model. Consequently, entrepreneurial orientation is corelated with knowledge creation. Keywords: SME’s, entreprenurial orientation, knowledge creation. Introduction More and more studies have paid attention to the relationship between knowledge, and entrepreneurship (Moller, 2007; Miller et al., 2007). We believe that a better understanding of the interaction between entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation processes impact on the company performance. With better knowledge individuals, companies and the economy can develop better skills that will contribute to higher competitiveness. Based on a study of links between entrepreneurial orientation and creating new knowledge, we determined how individual factors are interconnected. This paper is structured as follows, first theoretical background and discussion EO and KC, in the second part we make empirical test of correlation between EO and KC. Empirically test based on 195 samples collected through questionaire send to entrepreneurs and executives in Slovenian firms. 2. Research background and hypotesis Knowledge has to become the key economic resource and the dominant – and perhaps even the only –source of competitive advantage” (Drucker, 2009). Knowledge economy based on creating, evaluating, and trading knowledge. Labour cost, become progressive less important and traditional economic concepts such as scarcity to resources and economies of scale case to apply. Of all factors of production knowledge capital creates the longest lasting competitive advantage. It’s based on Knowledge-based theory, which considers knowledge as the most strategically significant resource of a firm. Teece, Pisano and Shuen (1997) and others (Morgan, Vorhies, Mason, 2009) upgraded Knowledge based theory with Theory of dynamic firms capatibility. The theory assumes that the market environment is dynamic, heterogeneous sources that are not sufficient (Morgan, Vorhies, Mason, 2009, Teece, Pisano, Shuen, 1997). Trends, perspectives and market informations must be dynamic (Busenitz, Barney, 1997 in Holcomb, Ireland, Holmes; Hitt, 2009), thinking along established routes is not sufficient (Nonaka, 1991). The environment is changing constantly and rapidly as well as the market and customers’ needs (Prajogo, Ahmed, 2006). Constant and rapid changes in present networked, knowledge society give rise to new challenges to human competences (Paavaola, 1 Hakkarainen, 2005). Audretsch (2010) builds on the knowledge society to an entrepreneurial society. The entrepreneurial society assumes the role of physical capital and entrepreneurial capital upgraded with a knowledge capital, economic growth, job creation and competitiveness in a complex environment (Audretsch, 2010). Enterprise must know what to do, how to do it, when and where to do it to compete succesefuly. Without knowledge it is impossible (Korposh, Lee, Wei, Wei, 2011). Productive participation in knowledge intensive work requires that individual professional, their communities, and organizations continiusly surpass themselves they develop new competencies, advance their knowledge and understanding as well as produce innovations and create new knowledge (Paavola, Hakkarainen, 2005). Human work is more and more focused on deliberate advancement of knowledge than joust production of material things (Bereiter, 2002 in Paavola, Hakkarainen, 2005). Knowledge and innovation is widely considered a key prequisite for achiving organizational competitiveness and sustained long term wealth in an increasingly volatile business environment (Esterhuizen, Schutte, Toit, 2011). Organization learning improve innovation process and their effectiveness (Huang, Wang, 2011), and competitive advantage (Barsh, 2007). Entrepreneurial orientation Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) refers to a firm’s strategic orientation and entrepreneurial activities, which captures specific entrepreneurial decision-making, such as taking calculated risks, being innovative and proactive (Covin and Slevin, 1989; Lumpkin and Dess, 1996). Entrepreneurial orientation reflects how a firm operates rather than what it does (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). EO is reflected in the leadership skills, the integration of proactive and aggressive initiative and turning competitive environment to their advantage (AtuatheneGima, 2001). EO companies have competences to respond quickly and take advantage in niche market (Zahra, Covina, 1995), they innovate and take risks on positioning new product strategy (Miller, Friesen, 1982). EO is composed of processes, structures and habits (Lumpkin, Dess, 1996), contains the following dimensions: innovation, risk taking, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness and autonomy (Miller, 1983; Covina, Slevin, 1991; Lumpkin, Dess, 1996). Each of these dimensions can be studied independently expressed differently (Kreiser, Marino, Weaver, 2002; Lamadrid, et al., 2008; Lumpkin, Dess, 1996, 2001 Rauch et al., 2009). Each dimension can be reflected complementary to the other, or in conjunction with them (Lyon et al., 2000). Innovation is defines innovation as: the successful generation, development and implementation of new and novel ideas , which introduce new products, processes and / or strategies to a company oe enhance current products, processes and/or strategies leading to commercial success and possible marketing leadership and creating value for shareholders, driving economic growth and improving standard of living (Katz, 2007). Risk-taking (Cantillon, 1730 in Jun, Deshoolmeester, 2006) is associated with entering in unknown field, with the involvement of their own and other resources to operate in an uncertain environment. It is important to reduce and manage risks. 2 Proactiveness is response and explore opportunities for products and services, to achieve advantages over its competitors and offers adjustments for future demand. Proactivity is reflected in relation to market opportunities. Competitive aggressiveness (Lumpkin, Dess, 2001, p. 431) is reflected in the intensity of response to competitors. Monitored by organizations such as the intensity of response to other bidders rivals. The activities of competitors can be sharp and decisive response, or lukewarm. Competitive aggressiveness is reflected as a challenge to enter the market and improve market position. Autonomy is reflected in the self-initiative to exploit opportunities (Lumpkin, Dess, 1996). Autonomy (Burgelman, 1984; Hart, 1992) is inherently a creative entrepreneur, creative and wants to be independent, autonomous independence so important for entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial teams in the establishment and management of new business. Autonomy is an independent function performed by managers or teams who make decisions (Rauch et al., 2004). Autonomy (Lumpkin, Dess, 2001, p. 431) is defined as an independent individual or team activity, which combines the design of the vision and its implementation. Hypothesis H1. Entrepreneurial orientation is five dimensoin process. Knowledge creation Knowledge is the fundamental source of competitiveness and success of the company. Knowledge is formed and exist in the minds of the people, for the creation of new ideas is an important interaction between individuals (Davenport, Prusak,2000; Nonaka, 1994). Nonaka, Toyama and Konno (2000) note that knowledge creation is necessarily context depend in terms of who participate and how they participate. From the perspective of resourceadvantage theory, knowledge is not easily transferred and dispersed due to its characteristics of tacitness and immobility (Grant, 1996; Hunt, Arnett, 2006; Hunt, Morgan, 1996). Knowledge creation (KC) process allows firms to amplify knowledge embedded internally and transfer knowledge into operational activities to improve efficiency and create business value (Nonaka, Konno, 1998; Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1995; Nonaka, Toyama, Nagata, 2000). KC include elements of EO and market orientation, which is further converted into knowledge capital, which can be transmitted between other employees (Li, Huang, Tsai, 2008). Corporate culture and leadership encourage people to communication, collaboration and social interaction (Chen, Huang, Li 2007, Huang, Tsai, 2009). Social cohesion provides an effective combination of knowledge from different areas of expertise (De Luca, AtuaheneGima, 2007). Interacting with a combination of knowledge comes to the extent that good interpersonal relationships (Floyd, Lane, 2000, in De Clecq et al., 2009), provided that atmosphere of honesty, trust and support organization (Kuratko et al., 2005). New insights affecting entrepreneurial behavior and allow the ability to successfully exploit opportunities (De Clecq et al., 2009). Important as the quantity and quality of information to be exchanged (Birckshaw, 2000 in Williams, Lee, 2009). Entrepreneurs need to replace the existing knowledge with the new, to recognize what is no longer optimal positioning for the organization, and develop an organization's ability to operate on tomorrow's market (Hamel, 3 Prahalad, 1994). It is necessary to balance between research and development eksploativnim (March, 1991 Renko, Carsrud, Brännback, 2009). Based on the Theory of knowledge creation, knowledge is created through a spiral process of socialization, externalization, combination, According to Nonaka’s knowledge creation (SECI) model an organization create knowledge through dynamic process through interactions amongst individuals and organizations, interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge (Nonaka, 1991, 1994, Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1995; Nonaka, Toyama, Konno, 2000; Lin, Lin, Huang, 2008). We call the interaction between the two types of knowledge `knowledge conversion'. Through the conversion process, tacit and explicit knowledge expands in both quality and quantity. In the organization, knowledge ‘becomes’ or ‘expands’ through a four-stage conversion process (SECI) (Nonaka, von Krogh, Voepl, 2006): (1) socialization (from tacit knowledge to tacit knowledge); (2) externalization (from tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge); (3) combination (from explicit knowledge to explicit knowledge); and (4) internalisation (from explicit knowledge to tacit knowledge). Socialisation is the process of converting new tacit knowledge through shared experiences. Since tacit knowledge is difficult to formalise and often time- and space-specific, tacit knowledge can be acquired only through shared experience, such as spending time together or living in the same environment. Socialisation typically occurs in a traditional apprenticeship, where apprentices learn the tacit knowledge needed in their craft through hands-on experience, rather than from written manuals or textbooks. Socialisation may also occur in informal social meetings outside of the workplace, where tacit knowledge such as world views, mental models and mutual trust can be created and shared socialisation also occurs beyond organizational boundaries. Firms often acquire and take advantage of the tacit knowledge embedded in customers or suppliers by interacting with them. Externalisation is the process of articulating tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge. When tacit knowledge is made explicit, knowledge is crystallised, thus allowing it to be shared by others, and it becomes the basis of new knowledge. Concept creation in new product development is an example of this conversion process. The successful conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge depends on the sequential use of metaphor, analogy and model. Combination is the process of converting explicit knowledge into more complex and systematic sets of explicit knowledge. Explicit knowledge is collected from inside or outside the organization and then combined, edited or processed to form new knowledge. The new explicit knowledge is then disseminated among the members of the organisation. Creative use of computerised communication networks and large-scale databases can facilitate this mode of knowledge conversion. The combination mode of knowledge conversion can also include the `breakdown' of concepts. Breaking down a concept such as a corporate vision into operational business or product concepts also creates systemic, explicit knowledge. Internalisation is the process of embodying explicit knowledge into tacit knowledge. Through internalisation, explicit knowledge created is shared throughout an organisation and converted into tacit knowledge by individuals. Internalisation is closely related to `learning by doing'. Explicit knowledge, such as the product concepts or the manufacturing 4 procedures, has to be actualised through action and practice. By reading documents or manuals about their jobs and the organisation, and by rejecting upon them, trainees can internalise the explicit knowledge written in such documents to enrich their tacit knowledge base. Explicit knowledge can be also embodied through simulations or experiments that trigger learning by doing. When knowledge is internalised to become part of individuals' tacit knowledge bases in the form of shared mental models or technical know-how, it becomes a valuable asset. This tacit knowledge accumulated at the individual level can then set off a new spiral of knowledge creation when it is shared with others through socialisation. In knowledge conversion, personal subjective knowledge is validated, connected to and synthesized with others’ knowledge (Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1995). Hypothesis H2. Knowledge creation process iz four dimension process Entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation process Entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviors are critical for new ventures to facilitate the utilization of new and existing knowledge to discover market opportunities (Wiklund, Shepherd, 2003). KC processes such as socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization (SECI) describe a spiral of interactions between explicit and tacit knowledge (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka, Konno, 1998). Firms exchange and transform knowledge continuously through dynamic self-transcendental processes (Nonaka, Konno, 1998; Nonaka et al., 2000). When developing EO, ventures can exploit the dynamic SECI spiral to create and share knowledge dispersed among individual members. Firms with innovativeness may have a tendency to support new ideas and novelty, and further increase the engagement in developing new products, services, or processes (Lumpkin, Dess, 1996). The development of new products and services involves extensive and intensive knowledge activities. The knowledge conversion provides value to their customers and help to make competitive position in the market (Griffith et al., 2006). The organization creates a new combination of resources and products, intended to upcoming changes, opportunities and entry to market and take advantege to exploit opportunities (Lumpkin, Dess, 2001). The SECI spiral can facilitate knowledge conversion and transformation into new types of knowledge (Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1995). In knowledge conversion, new product development or marketing activities starts with socialization (Nonaka & Toyama, 2005). Socialization processes such as direct interaction, brainstorming, and informal meetings help employees to share and exchange valuable knowledge (Zhang, Lim, & Cao, 2004). Entrepreneurs explore business opportunities and promote innovation (Lumpkin, Dess, 1996), and they should motivate employees to take risks to deal with the challenging and creative activities. Employees need socialization process to build more interaction to exchange tacit knowledge, solve problems, and avoid mistakes (Nonaka, Takeuchi, Umemoto, 1996; Quinn, 1992). Externalization activities articulate tacit knowledge into explicit forms. Through externalization, employees can understand new product development and increase their involvement in the activities of articulating tacit knowledge into substantial concepts and 5 notions (Nonaka, Konno, 1998; Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1995; Nonaka, Toyama, 2005). Combination process can make innovative ideas more usable, thereby crystallizing knowledge into new products or services. Internalization process promotes the actualization of new product innovation or improvement within the organization. The newly created knowledge and existing knowledge are then combined, edited, or processed to form more complex and explicit knowledge through the combination process (Nonaka, Konno, 1998). The use of documents, meetings, and computerized communication networks facilitates this mode of knowledge conversion. Internalization activities accumulate and systemize the experiences and concepts of employees to the organizational tacit knowledge. Autonomous orientation reflects the ability to be self-directed in the pursuit of market opportunities (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). Employees need autonomy and the independent assortment and selection activities to achieve the goals (Li, Huang, Tsai, 2009). Socialization process makes employees build interaction to freely exchange highly personal or professional knowledge. To translate tacit knowledge into understandable forms, the firm engages in externalization activities such as action, experimentation, and observation. The combination activities edit and integrate knowledge by using documents or databases to generate new knowledge application. Through internalization activities, employees learn by doing autonomously to enrich their experiences and accumulate valuable know_how in an organization (Nonaka et al., 1996). The acquisition of knowledge is associated with learning at work, learning from work or learning by doing. In entrepreneurial firms sharing knowledge within the company led to the creation of new knowledge and its diffusion across an enterprise (Cohen, Levinthal, 1990). This is reflected in the use of knowledge (Li et al., 2009). Wiklund and Shepherd (2003) note a positive relationship between resources, knowledge-based, and performance of the organization. Hoegl and Schultze (2008) compared the creation of knowledge through the processes of creating knowledge - which are defined by Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995): socialization, externalization, internalisation and socialization - through the generation of ideas for new products. They found a positive correlation between idea creation to the processes of socialization and internalisation and externalization of negative correlation and the combination. Grant (1996), Spender (1996), Teece (2000), Watson and Helvet (2006, Li et al., 2009) observed correlation with innovation and creating knowledge through the collection and its use in the enterprise. Business-oriented reorganization often directly supports generative learning by focusing management to identify and exploit new opportunities and motivates employees to move from the pressure armor routine work (Cui, Zheng, 2007). A high degree of entrepreneurial orientation involves long-term development guidelines vision, mission, work with customers, setting up new capacities. Realizing the vision of entrepreneurs is related to the double loop learning (Cui, Zheng, 2007). According to the above, SME's with entrepreneurial orientation are more prone to focus attention and effort towards knowledge creation process. The SECI spiral can utilize the full potential of knowledge and further facilitate its creation and utilization within the firm, 6 which facilitates the transformation and activation of entrepreneurial orientation. We can reasonably expect the positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation process. Hypothesis 3. Entrepreneurial orientation will be in correlation with knowledge creation process. Research methods 3.1. Sample and data collection We employed a questionnaire survey approach to collect data, and all items required fivepoint Likert-style responses ranged from 1=“strongly disagree,” through 3=“neutral,” to 5=“strongly agree.” Explain sample 2500 questionnaires were mailed to executive managers SME's in Slovenia. We selected the firms with more than 6 and less than 250 employees. We asked respondents (entrepreneurs or executives) to evaluate their level of agreement with each of questions. 203 responses were received and eight of them were incomplete. The remaining 195 valid and complete questionnaires were used for the quantitative analysis. It represented a useable response rate of 7,8% Table 1. Within each company, we collected the measures of knowledge creation process, innovativeness and company performance. A principal component factor analysis on the questionnaire measurement items yielded seven factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 that accounted for 69.67% of the total variance, and factor 1 accounted for 16.46% for the variance. Since several factors, as opposed to one single factor, were identified and the first factor did not account for most of the variance, common method bias is unlikely to be a serious problem in the data (Podsakoff , Organ, 1986). Table: Comparison between sent and returned questionnaires according to the number of full and part-time employees Sent questionnaires Returned questionnaires Percentage Percentage No. of employees Frequency (%) Frekvenca (%) 57 6–9 968 38,72 28,64 62 10–19 853 34,12 31,16 46 20–49 480 19,20 23,12 24 50–99 129 5,16 12,06 10 100–250 70 2,80 5,02 4 No answer 203 Cumulative 2500 3.2. Measures 7 3.2.1. Knowledge creation process This study used a five-point scale, adapted from Sabherwal and Becerra-Fernandez (2003), to measure knowledge creation process variable. The four dimensions of knowledge creation process were socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization (Nonaka, 1994; Nonaka et al., 2000; Sabherwal & Becerra-Fernandez, 2003). Four items measured socialization: cooperative projects across directorates, the use of apprentices and mentors to transfer knowledge, brainstorming retreats or camps, and employee rotation across areas. Five items measured externalization: a problem-solving system based on a technology like case-based reasoning, groupware and other collaboration learning tools, pointers to expertise, modeling based on analogies and metaphors, and capture and transfer of experts' knowledge. Four items measured combination: web-based access to data, web pages, databases, and repositories of information, best practices, and lessons learned. Three items measured internalization: on-the-job training, learning by doing, and learning by observation. 3.2.2. Entrepreneurial orientation Drawing upon previous studies (e.g. Lumpkin & Dess, 1996, 2001; Miller, 1983), entrepreneurial orientation was measured with five dimensions: innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, competitive aggressiveness, and autonomy. Innovativeness refers to a willingness to support creativity and experimentation in introducing new products/services, and novelty, technological leadership and R&D in developing new processes. Risk-taking means a tendency to take bold actions such as venturing into unknown new markets, committing a large portion of resources to ventures with uncertain outcomes, and/ or borrowing heavily. Proactiveness refers to how firms relate to market opportunities by seizing initiative in the marketplace. Competitive aggressiveness refers to how firms react to competitive trends and demands that already exist in the marketplace. Autonomy is defined as independent action by an individual or team aimed at bringing forth a business concept or vision and carrying it through to completion. Innovativeness refers to a willingness to support creativity and experimentation in introducing new products/services, and novelty, technological leadership and R&D in developing new processes. Drawing upon previous studies (e.g. Lumpkin & Dess, 1996, 2001; Miller, 1983), innovativenss as one of five dimensions etrepreneurial orientation was measured with: three questions. 3.Analysis and results We first performed for all variables descriptive analysis and to establish their suitability for statistical analysis using factor analysis. Then we performed ekplorativno and then continue konfirmativno factor analysis, and in the end we are structured modeling method to check the validity of the model equations. Exploratory factor analysis was performed with the software package SPSS 18. This analysis provided an answer on what the basic explanatory variables. Each theoretical construct, we specifically checked and, where necessary, reduce the number of 8 variables. For further analysis of the construct of entrepreneurial orientation, we keep five sub-dimensions. Two of them are explained by two variables, the rest with three variables. To analyze the construct of market orientation we kept seven subdimensions, one is explained by two variables, three by three variables, one has four, six and seven variables. For further analysis of the construct dimensions of knowledge creation, we keep the four sub-dimensions, one is explained by the three variables and other variables of five. Because we were interested in business performance, was included in the integrated model, the dimensions of business performance. Just-what we in accordance with theoretical standards developed with three sub-dimensions, which we call the profitability, growth and efficiency. Each of these three variables explain All the set constructs were verified by factor analysis and konfirmativno with structured equation modeling with EQS software package 6.1. We confirmed the validity of the results of the exploratory analysis demonstrated the reliability of the measurement model and its convergent and discriminatory validity. Thus we have proved Multidimensionality model and its comparability, as most indices suitability of the integrated model of excellent value. Calculations and exploratory factor analysis konfirmativne and structural equation modeling, we examined the control variables, namely, we checked the calculations for the case of companies with more or fewer than 20 employees and with more or less than 2 million euros. Calculations of the control variables confirmed the number of sub-dimensions and variables as well as the validity of the constructs of the structural model, the validity of hypotheses related to the exogenous part of the construct The results of the study are closing the gap in research theory, based on the resources and on the theory and complementary mosaic of research conducted in different countries, a survey among Slovenian companies. The results of empirical analysis, an additional doctoral dissertation, which includes different dimensions of attitudes, their inter-relations and contribution to the success of the organization. From the results of research showing the relationship of entrepreneurial orientation, market orientation and knowledge creation process between Slovenian small and medium-sized enterprises. The results allow a better understanding of the dynamic internal processes within the company, the development offers proactive, knowledge creation and performance in a dynamic and competitive environment and the correlation matrix of the variables. To test the hypothesized relationships in our path-analytic framework, we employed LISREL (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988; Joreskog & Sorbom, 1986). Calculating parameter estimates and standard errors that can be used to test statistical significance, LISREL also analyzes hypothesized relationships. The hypotheses were examined using LISREL 8.52. Paths between constructs represent individual hypotheses, and each was assessed for statistical significance of the path coefficient. This study tested hypothesized relationships with a full model, and the LISREL analysis of this model produced a chi-square of 72.05 (df=40). In addition to this chi-square value, the various goodness-of-fit indices also suggested a very good fit (GFI=0.932, AGFI=0.867, NFI =0.975, CFI=0.989, RMSR=0.0124). The analysis also provided support for the first three study's hypotheses. The results were reported in Table 4 and Fig. 1 showing the path coefficients, t-values, and construct relationships. 9 As hypothesized, there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance (γ11=0.47, t=7.32). Therefore, H1 is supported. Results uphold the proposition that the two concepts are indeed related and, therefore, support the conclusions, which postulate that entrepreneurial orientation is important to enhance firm performance. A positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation process is established (γ21=1.19, t=11.70). Therefore, H2 is supported. As scholars have postulated, perhaps the firms in newventures may be better served by adopting appropriate entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation process. As predicted, there is a significantly positive relationship between knowledge creation process and firm performance (β12=0.52, t=8.26). Therefore, H3 is supported. The finding may add to the understanding that every knowledge creation process is indeed necessary and may be linked to performance, which adds further credence to the knowledge creation theory. An empirical study with mediator must propose that (1) the independent variable significantly influence the mediating variable, (2) the independent variable significantly influence the dependent variable without the mediator, and (3) the inclusion of the mediator attenuates the relationships between the independent and the dependent variables while showing a significant relationship between the mediator and the dependent variable (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The independent variable was entrepreneurial orientation, and the proposed mediating variable was knowledge creation process. The dependent variable was firm performance. We tested the three conditions by using LISREL analysis. First, we examined the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge creation process to determine if they had significant relationship. Results show that entrepreneurial orientation has significantly positive relationship with knowledge creation process (γ21=1.08, t=13.13). Thus, the first condition for mediating effect is met. Then, the relationship between the independent and the dependent variable show that entrepreneurial orientation has significantly positive relationship with firm performance (γ11=1.31, t=11.91), also supporting the second condition. In the third condition, entrepreneurial orientation has significantly positive relationship Napaka! Predmetov ne morete ustvariti z urejanjem kod polj. 10 0.67 PNPT 0.74 E132* PNKA 0.85 E133* PNA 0.88 E134* PNI 0.58 E135* PNP 0.52 E136* KZS 0.65 E144* KZE 0.61 E145* KZK 0.54 E146* KZI 0.70 E147* 0.53* F1* 0.48* 0.82* 0.86* 0.78* 0.76 0.79* F2* 0.84* 0.72* Figure X: EQS 6 kor Chi Sq.=48.94 P=0.00 CFI=0.96 RMSEA=0.11 Figure EQS12 korel Chi Sq.=45,58; P=0,06; CFI=0,97; RMSEA=0,08; Table 4 Standardized path estimates a. Hypothesized relationships Hypothesis Variables Path coefficient tvalue Result H1 Entrepreneurial orientation will be positively related to firm performance. 0.47⁎ 7.32 Supported H2 Entrepreneurial orientation will be positively related to knowledge creation process. 1.19⁎ ⁎ 11.70 Supported H3 Knowledge creation process will be positively related to firm performance. 0.52⁎ ⁎ 8.26 Supported *pb0.05, **pb0.01. a n=165 (two-tailed test). 3.3. Reliability and validility Reliability of the multi-item scale for each dimension was measured using Cronbach alphas and composite reliabilities measures. Both measures of reliability were above the recommended minimum standard of 0.60 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Baker, Parasuraman, Grewal, & Voss, 2002; Nunnally, 1978). For all twelve dimensions, both measures of reliability are above 0.70. Table 2 summarizes all measurement items, Cronbach alphas, composite reliability, and their scales for all the items. EQS 12 provides a chi-square value and five additional indices that assess the fit of path models, the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), the normed fit index (NFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the root mean square residual (RMSR). 11 The fit indexes of confirmatory factor analysis for the measurement models ranged from adequate to excellent (entrepreneurial orientation: GFI=0.98, AGFI=0.92, NFI=0.93, CFI=0.96, RMSR=0.02; knowledge creation process: GFI=0.96, AGFI=0.81, NFI=0.93, CFI=0.96, RMSR=0.01; firm performance: GFI=0.92, AGFI=0.85, NFI=0.93, CFI=0.95, RMSR=0.04). Additionally, three models had chi-squares less than three times their degrees of freedom (entrepreneurial orientation, 139.63/60=2.33; knowledge creation process, 219.98/ 100=2.12; firm performance, 63.27/24=2.64). Overall, the CFA results suggested that the models of entrepreneurial orientation, knowledge creation process, and firm performance provided a good fit for the data. According to Anderson and Gerbing (1988), convergent validity can be assessed from the measurement model by determining whether each indicator's estimated pattern coefficient on its posited underlying construct factor is significant (greater than twice its standard error). Convergent validity was assessed using the t-statistics for the path coefficients from the latent constructs to the corresponding items. As mentioned above, all the path coefficients from the three constructs to the twelve measures are statistically significant, with the highest t-value for the items measuring entrepreneurial orientation being 9.33 and the lowest t-value for the items measuring firm performance being 2.02. That all the t-values exceed the standard of 2.00 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988) indicates satisfactory convergent validity for all twelve dimensions. Discriminant validity was assessed in three ways (Baker et al., 2002). First, the confidence interval for each pairwise correlation estimate (i.e., ±two standard errors) should not include 1 (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). This condition was satisfied for all pairwise correlations in three measurement models. Second, for every construct, the percentage of variance extracted should exceed the construct's shared variance with every other construct (i.e., the square of the correlation) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hult, Hurley, Giunipero, & Nichols, 2000). As may be seen from Table 3, this condition is also satisfied for all the constructs. For example, the extracted variance for innovativeness is 5. Discusion and conclusion Literature on knowledge management pertaining to the capturing, locating, transferring, and sharing of primarily existing knowledge (von Krogh, Ichijo, Nonaka, 2000). This study develops a conceptual model to examine the mediating role of knowledge creation process in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. The results show that entrepreneurial orientation can positively enhance firm performance; however, if we add knowledge creation process as a mediator, the directly positive relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance will attenuate. It specifically implies that entrepreneurial orientation indirectly influences firm performance by influencing knowledge creation process. Thus, knowledge creation process plays a mediating role through which entrepreneurial orientation benefits firm performance. 12 Our findings contribute to theoretical development in several ways. First, while the importance of entrepreneurial orientation in firm performance has been recognized, the link between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance has remained inconsistent (Lumpkin & Dess, 1996). This study reveals that entrepreneurial orientation is critical to business ventures and has positive impact on firm performance, which gives additional grounding for statements about the positive effect of entrepreneurial orientation on firm performance (e.g. Barringer & Bluedorn, 1999; Lumpkin & Dess, 2001; Wiklund & Shepherd, 2003; Zahra & Covin, 1995). The inclusion of knowledge creation process as a mediating variable may help to enhance our understanding of howentrepreneurial orientation affects firm performance. Our findings support recent arguments for a contingency perspective on the entrepreneurial orientation — firm performance link (Lumpkin & Dess, 2001) and make a contribution to the entrepreneurship literature by clarifying the role that knowledge creation process plays. Second, the emergent model provides empirical support of Nonaka's (1994) theory of knowledge creation. The findings demonstrate the mediating effect of knowledge creation process when new ventures want to execute entrepreneurial orientation to achieve firm performance. We place primary emphasis on the dynamic processes rather than the outcomes of knowledge creation (Nonaka,1994; Nonaka & Konno,1998; Nonaka et al., 2000a). Tacit and explicit knowledge is connected and converted by the interactive spiral process of socialization, externalization, combination, and internalization. The dynamic SECI model enables the firm to create new knowledge or combine existing knowledge to form new insights and become valuable knowledge assets for the use of firms. New ventures can amplify the mobilization of knowledge and trigger new spirals of knowledge creation continuously to transform entrepreneurial orientation into better business value and performance. Furthermore, the consideration of knowledge creation process makes a related support of the resource-advantage theory. According to the resource-advantage theory, knowledge embedded internally is a valuable resource because it is unique to create and difficult to imitate (Barney, 1991; Grant, 1996; Hunt & Morgan, 1996; Zack, 1999). The findings reveal that SECI spiral enhances the capabilities of new ventures to transform tacit knowledge into the organizational memory and thereby leads to improved efficiency, growth, and profit. This result joins other studies to highlight the strategic value of knowledge creation for firms to sustain competitive advantages (Chia, 2003; Grant, 1996; Lee & Choi, 2003; Matusik & Hill, 1998; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995). Finally, this study contributes to integrate the domains of entrepreneurial orientation and knowledge management research. Entrepreneurship literature (e.g. Lee et al., 2001; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000) suggests that entrepreneurial orientation of new ventures is critical for their success because entrepreneurial orientation represents an important means to discover and exploit profitable business opportunities. Knowledge management literature (e.g. Grant, 1996; Nonaka et al., 2000a,b; Zack, 1999) emphasizes the value of leveraging knowledge and creating newcombinations.We showhere that the conversion process of knowledge creation appears to be a key mechanism through which entrepreneurial orientation is developed and implemented to accomplish favorable firm performance. From a practical point of view, our study suggests that managers should be aware of the importance of knowledge creation process in the link of entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. 13 Managers have to facilitate dynamics and spiral of knowledge creation by taking a leading role in managing the SECI process. Firms can amplify and enlarge knowledge through the dynamic conversion between tacit and explicit knowledge. Managers need to nurture an enabling environment that allows employees to share and exchange tacit knowledge to create new knowledge. Each mode of knowledge conversion requires different approaches for knowledge to be created and shared effectively (Nonaka & Konno, 1998; Nonaka et al., 2000b). For example, employees rely on shared experiences such as apprenticeship or practice to build mutual understanding and trust in the socialization process. In externalization, the use of metaphors in dialogue is essential for concept creation. Combination process can disseminate knowledge by utilizing information technology such as on-line network, groupware, and database. Knowledge is articulated and embodied through simulations or experiments in the internalization process. Thus, managers should carefully choose and design appropriate methods according to the SECI process to facilitate knowledge creation. Furthermore, firms need to enhance employees' involvement and participation in SECI activities. Managers should provide incentive and support to reinforce the desired behaviors of knowledge creation. Employees will be motivated to exchange, learn, and create knowledge and further transform knowledge to fulfill strategic objectives and execution. This study has some inherent limitations. First, our cross-sectional design prevents us from studying causal relationships among our variables. A longitudinal investigation would provide further insights into the dynamic nature of knowledge creation and different organizational levels. Future researches might use longitudinal design to drawcausal inferences of our model. Second, this study goes further than other studies in examining a potential mediator in the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance. However, we do not consider the roles played by organizational routines, cultures, and other possible knowledge management processes such as knowledge accumulation and knowledge integration. In addition, we also know that often the firm's orientation looks like its manager. If the manager is changed or changes, entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance may be influenced. Future studies might gain additional insights by exploring other potential mediators such as organizational factors, other knowledge management processes, or the change of manager. Third, the firm age of this study is restricted within ten years and the majority of our response samples are small and medium enterprises. Larger firms tend to have sufficient resources or money to invest in knowledge management process. Future research could overcome this limitation by expanding the scope of studies to include larger and elder firms. Fourth, the study is based on self-report data incurring the possibility of common method bias. However, our tests of common method variance do not find it to be a significant problem in this study. We also use multiple assessments including Cronbach alphas, composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity to support the accuracy of the data and the results. Future studies might use objective measures for firm performance to strengthen the research design. In summary, entrepreneurial orientation is critical for enhancing firm performance. Our study highlights the crucial importance of the mediating role of knowledge creation process when examining the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and firm 14 performance. The viewpoints proposed in this study have important implication for new ventures in today's dynamic and competitive environment. The first responsibility of management is to unleash the potential of an organizational knowledge into value creating activities (von Krogh, Ichijo, Nonaka, 2000). Knowledge capital can be dynamically deployed and redeployed to form the basis for competitive advantage (Teece, 2000). References 1. Barsh, J. (2007). Innovation Management: A conversation with Gary Hamel and Lowell Bryan. The McKinsey Quarterly, 3, 1–10 2. Bereiter, C. (2002). Education and mind in the knowledge age. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NY. Capedaa, G. & Vera, D. (2007). Dynamic capabilities and dynamic capabilities: a knowledge next term management perspective. Journal of business research, 60( 426437. 3. Covin, J.G. & Slevin, D.P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal 10: 75–87. 4. Davenport, T. & Prusak, L. (2000). Working knowledge: how organizations manage, what they know.Boston: Harvard business school press. 5. Drucker, P.F. (2009). A century of social transformation:emergence of knowledge society. In managing in a time of great change. Boston: Harvard business press, 177-230. 6. Essmann, H.E. (2009). Toward innovation capatibility maturity.Ph.D.thesis, University of Stelenbosch. Esterhuizen, D., Schutte, C.S.L. & du Toit, A.S.A. (2011). Knowledge creation process as critical enablers for innovation. International journal of information management. 7. Fischer, M.M. & Fröhlich, J. (2001). Knowledge complexity and innovation system. Springer. 8. Gray, (2000). Knowledgemanagement overview. Irwine, CA: University of California. 9. Hoegl, M. & Shulze, A. (2005). How to support knowledge creation in new product development: an investigation methods. European management journals,23 (3), 263273. 10. Huang, S.K.& Wang, Y.,L. (2011): Entrepreneurial orientation, learning orientation and innovaton in small and medium enterprises. Procedia social and behavioural sciences, 24, 463-570. 11. Katz, B. (2007). Integration of project management processes with methology to manage radical uinnovation project. M.Sc disertation University of Stelenbosch. 12. Kleinsmann, M., Buijs, J. & Valkenburg, R. (2010).Understanding the complexity of knowlege integration in collaborative new product development teams: a case study. Journal of engineering and technology management, 27(1-2), 20-32. 13. Korposch, D., Lee, Y.C, Wei, C.C. & Wei, C.S. (2011). Modelling the effects of existing knowledge on creation of new knowledge. Concurrent engineering: research and applications, 19(3), 225- 233. 14. Li, Y.H., Huang, J.W. & Tsai, M.T. (2009). Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: the role of knowledge creation process. Industrial marketing management, 38, 440-449. 15 15. Li, Y, Liu, X., Wang, L., Li, M. & Guo, H. (2009). How entrepreneurial effect on knowledge management on innovation. System research and behavioural science, 26, 645-660. 16. Lumpkin, G.T. & Dess, G.G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of management review, 21 (1), 135-172. 17. Malone, D. (2002). Knowledge management: a model for organizational learning. International journal of accounting informational systems, 3(2), 111-123. 18. McAdam, R. (2004). Knowledge creation and idea generation: a critical quality perspective. Technovation, 24, 697-705. 19. Miller D.J., Fern, M.J. & Cardinal, L.B. (2007). The use of knowledge for technological innovation within diversified firms. Academy of management journal, 50, 308–326. 20. Moller C. (2007). Process innovation laboratory: a new approach to business process innovation based on enterprise information systems. Enterprise information systems 1(1), 113–128. 21. Murphy, G. B., Trailer, J. W., & Hill, R. C. (1996). Measuring performance in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Research, 36(1), 15−23. 22. Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization science, 5 (1), 14-37. 23. Nonaka, I. (1991). The knowledge-creating company. Harvard business review, 69, 96105. 24. Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company. Oxford university press. 25. Nonaka, I., Toyama, R. & Konno, N. (2000). SECI, ba and leadership: a unified model of dynamic knowledge creation. Long range planning, 33 (1), 5-34. 26. Nonaka, I., von Krogh, G. & Voepel, S. (2006). Organizational knowledge creation: evolutionary paths and future advances. Organization studies, 27 (8), 1179-1208. 27. Paavola, S. & Hkkarainen, K. (2005). The knowledge creation metaphor – an emergent metaphor epistemological approach to learning. Science & education, 14, 535-557. 28. Prajogo, D.I.& Ahmed P.K. (2006). Relationships between innovation stimulus, innovation capacity, and innovation performance. R&D Management, 36 (5), 499–515 29. Samaddar, S. & Kadiyala, S.S. (2006). An analysis of interorganizational resorce sharing discusiopn in collaborative knowledge creation. European journal of operational research, 170, 192-210. 30. Teece, D.F. (2000). Strategies for managing knowledge assets: the role of firm structure and industrial context. Long range planning, 33, 35-54. 31. Von Krogh, G., Ichijo, K. & Nonaka I. (2000). Enabling knowledge creation: how to unlock the mystery of tacit. Oxford university press, 292. Franc Vidic Ph D Franc Vidic is Professor in the GEA College faculty for entrepreneurship. He is lecturer on marketing, and has published numerous articles and books on marketing, entrepreneurship and knowledge creation. Address: GEA College, faculty for entrepreneurship, Dunajska cesta 156,1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia. Email: franc.vidic@gea-college.si 16 1. 2. 3. 4. Entrepreneurial Orientation, Organizational Learning, and Performance: Evidence From China Yongbin Zhao1, Yuan Li1, Soo Hoon Lee2,*, Long Bo Chen1 Article first published online: 16 MAR 2011 DOI: 10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00359.x 17