NEOLITHIC_REVOLUTION_1 - Mr. Grande`s World History

advertisement

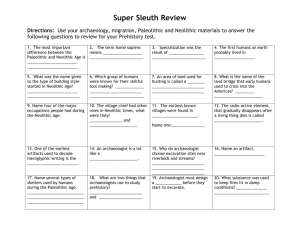

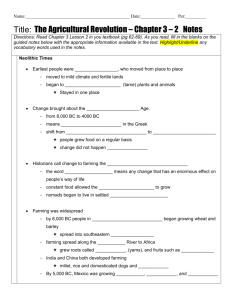

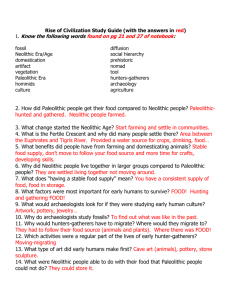

Pre-Modern World History, Mr. Grande Historiography: The Practices and Pitfalls of History The Neolithic Conversion Source: McKay, John P, Hill, Bennett D., Buckler, John. A History of World Societies: Volume I to 1715. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company (1996). THE PALEOLITHIC AGE Paleolithic peoples hunted a huge variety of animals, ranging from elephants in Spain to deer in China. The hunters were thoroughly familiar with the habits and migratory patterns of the animals on which they relied. But success in the hunt also depended on the quality and effectiveness of the hunters' social organization. Paleolithic hunters were organized—they hunted in groups. They used their knowledge of the animal world and their power of thinking to plan how to down their prey. Paleolithic peoples also nourished themselves by gathering nuts, berries, and seeds. Just as they knew the habits of animals, so they had vast knowledge of the plant kingdom. Some Paleolithic peoples even knew how to plant wild seeds to supplement their food supply. Thus they relied on every part of the environment for survival. The basic social unit of Paleolithic societies was probably the family, and family bonds were no doubt stronger and more extensive than those of families in modern, urban, and industrialized societies. It is likely that the bonds of kinship were strong not just within the nuclear family of father, mother, and children but throughout the extended family of uncles, aunts, cousins, nephews, and nieces. People in nomadic societies typically depend on the extended family for cooperative work and mutual protection. The ties of kinship probably also extended beyond the family to the tribe. A tribe was a group of families led by a patriarch, a dominant male who governed the group. Tribe members considered themselves descendants of a common ancestor. Most tribes probably consisted of from thirty to fifty people. As in the hunt, so too in other aspects of life—group members had to cooperate to survive. The adult males normally hunted abroad and between hunts made stone weapons. The women's realm was primarily the camp, but women too ranged through the neighborhood gathering nuts, grains, and fruits to supplement the group's diet. The women's primary responsibility was the bearing of children, who were essential to the continuation of the group. Women also had to care for the children, especially the infants. Part of women's work, too, was tending the fire, which served for warmth, cooking, and protection against wild animals. Some of the most striking accomplishments of Paleolithic peoples were intellectual. They used reason to govern their actions. Thought and language permitted the lore and experience of the old to be passed on to the young. An invisible world also opened up to Homo sapiens. They developed the custom of burying their dead and leaving offerings with the body, perhaps in the belief that somehow life continued after death. Paleolithic peoples produced the first art. They decorated cave walls with lifelike paintings of animals and scenes of the hunt. Located deep in the caves, some of these paintings still survive. Paleolithic peoples also began to fashion clay models of pregnant women and of animals. The statuettes of pregnant women seem to express a wish for fertile women to have babies and thus ensure the group's survival. The wall paintings and clay statuettes of Paleolithic peoples represent the earliest yearnings of human beings to control their environment. THE NEOLITHIC AGE Hunting is at best a precarious way of life, even when the diet is supplemented with seeds and fruits. Paleolithic tribes either moved with the herds and adapted themselves to new circumstances or perished. Several long ice ages— periods when glaciers covered vast parts of Europe—subjected the small bands of Paleolithic hunters to extreme hardship. Not long after the last ice age, around 7000 B.C., some hunters and gatherers began to rely chiefly on agriculture for their sustenance. Others continued the old pastoral and nomadic ways. Indeed, agriculture evolved over the course of time. Neolithic peoples had long known how to grow crops. The real transformation of human life occurred only when large numbers of people began to rely primarily and permanently "on the grain they grew and the animals they domesticated. Agriculture made possible a more stable and secure life. Neolithic peoples were responsible for many fundamental inventions and innovations that the modern world takes for granted. First, obviously, is systematic agriculture as the primary source of food. Neolithic peoples developed the primary economic activity of the entire ancient world, and the basis of all modern life. With the settled routine of Neolithic farmers came the evolution of towns and eventually cities. Neolithic farmers usually raised more food than they could consume, and their surpluses gave rise to larger, healthier populations. Population growth in turn increased reliance on settled farming, for only systematic agriculture could sustain the growing numbers of people. Some surpluses of food could be bartered for other commodities, the Neolithic era also witnessed the beginnings of the large-scale exchange of goods. In time the increasing complexity of Neolithic societies led to the development of writing, prompted by the need to keep records and later by the urge to chronicle experiences, learning, and beliefs. The transition to settled life had a profound impact on the family. The shared needs and pressures that encourage extended-family ties are less prominent in settled than in nomadic societies. Bonds to the extended family weakened. In towns and cities, the nuclear family was more dependent on its immediate neighbors than on kinfolk. Nevertheless, the nomadic way of life and the family relationships it nurtured continued to flourish alongside settled agriculture. Dramatic evidence of this fact came to light on September 19, 1991, when a hiker in the Tyrolean Alps in Italy discovered the frozen body of a Neolithic herdsman. The corpse is the oldest found intact, and its preservation results from the man having been covered for some fifty-three hundred years by glacial ice. Although the discoverers did irreparable damage to the site, enough remains to give a unique impression of European nomadic life and a surprising glimpse of its sophistication. The "Iceman," as he is now called, was found equipped with the implements of everyday life. Among them are advanced bows and arrows that prove a remarkable knowledge of ballistics. A number of tools, some of bone, wood, and even copper, show that European people were making the transition from the Neolithic Age to the time when they relied primarily on metals for their tools. Dental evidence suggests that the Iceman's diet consisted of milled grain. These findings strongly suggest that the Iceman was a hunter and gatherer but also that he and his society depended on tilled grain as a vital part of their diet. The Iceman proves that nomadic and pastoral life could and did coincide peacefully with the emerging agricultural settlements. Often farmers and nomads bartered with one another, each group trading its surpluses for those of the other. Although nomadic peoples continued to exist throughout the Neolithic period and into modern times, the future belonged to the Neolithic farmers and their descendants. The development of systematic agriculture may not have been revolutionary, but the changes that it ushered in certainly were. Until recently, scholars thought that agriculture originated in the ancient Near East and gradually spread elsewhere. Contemporary work, however, points to a more complex pattern of development. For unknown reasons people in various parts of the world all seem to have begun domesticating plants and animals at roughly the same time, around 7000 B.C. Four main points of origin have been identified: (1) In the Near East, people in places as far apart as Tepe Yahya in modern Iran, Jarmo in modern Iraq, Jericho in Palestine, and Hacilar in modern Turkey raised wheat, barley, peas, and lentils. They also kept herds of sheep, pigs, and possibly goats. (2) In western Africa, Neolithic farmers domesticated many plants, including millet, sorghum, and yams. (3) In northeastern China, peoples of the Yangshao culture developed techniques of field agriculture, animal husbandry, pottery making, and bronze metallurgy. (4) In Central and South America, Neolithic peoples domesticated a host of plants, among them corn, beans, and squash. Once people began to rely on farming for their livelihood, they settled in permanent villages and built houses. The location of the village was crucial. Early farmers chose places where the water supply was constant and adequate for their crops and flocks. At first, villages were small, consisting of a few households. But by about 7000 B.C., as the population expanded and prospered, villages usually were transformed into walled towns. The fortifications were so large that they could have been raised only by a large labor force. They indicate that towns were developing social and political organization as well as growing in size and wealth. The fortifications, constructed by the whole community, would have been impossible without central planning. One of the major effects of the advent of agriculture and settled life was a dramatic increase in population. The number and size of the towns prove that Neolithic society was expanding. Early farmers found that agriculture provided a larger and much more dependable food supply than hunting and gathering. No longer did the long winter months bring the -threat of starvation. Farmers learned to store the surplus for the winter. Because the farming community was better fed than ever before, it was also more resistant to diseases that kill people suffering from malnutrition. Thus Neolithic farmers were healthier and longer-lived than their predecessors. The surplus of food had two other momentous consequences. First, grain became an article of commerce. The farming community traded surplus grain for items it could not produce itself. The community thus obtained raw materials such as precious gems and metals. Early towns in the region now known as Mesopotamia (see Map 1.1) imported copper from the north, and eventually copper replaced stone for tools and weapons. Trade also brought Neolithic communities into touch with one another, making possible the spread of ideas and techniques. Second, agricultural surplus made possible the division of labor. It freed some members of the community from the necessity of raising food. Some artisans and craftsmen devoted their attention to making the new stone tools that farming demanded—hoes and sickles for working in the fields and mortars and pestles for grinding grain. Other artisans began to shape clay into pottery vessels, which were used to store grain, wine, and oil and served as kitchen utensils. Still others wove baskets and cloth. People who could specialize in particular crafts produced more and better goods than any single farmer could. Until recently it was impossible to say much about these goods. But in April 1985 archaeologists announced the discovery near the Dead Sea in modern Israel of a unique deposit of Neolithic artifacts. Buried in a cave were fragments of the earliest cloth yet found, the oldest painted mask, remains of woven baskets and boxes, and jewelry. The textiles are surprisingly elaborate, some woven in eleven intricate designs. These artifacts give eloquent testimony to the sophistication and artistry of Neolithic craftsmanship. Prosperity and stable conditions nurtured other innovations and discoveries. Neolithic farmers improved their tools and agricultural techniques. They domesticated bigger, stronger animals, such as the bull and the horse, to work for them, and they invented tools such as the plow, which came into use by 3000 B.C. By then the wheel had been invented, and farmers devised ways of hitching bulls and horses to wagons. Neolithic farmers could raise more food more easily, because animals and machines were doing more of the work. In arid regions such as Mesopotamia and Egypt, farmers learned to irrigate their land and later to drain it to prevent the buildup of salt in the soil. Water diverted from rivers opened new land to cultivation and deposited layers of rich mud, which increased the fertility of the soil. Thus the rivers, together with the manure of domesticated animals, kept replenishing the land. One result was a further increase in population and wealth. Irrigation, especially on a large scale, demanded group effort. The entire community had to plan which land to irrigate and how to lay out the canals. Then everyone had to help dig the canals. The demands of irrigation thus underscored the need for strong central authority within the community. Successful irrigation projects in turn strengthened such central authority by proving it effective and beneficial. Thus corporate spirit and governments to which individuals were subordinate— the makings of urban life—began to evolve. The development of systematic agriculture was a fundamental turning point in the history of civilization. Farming gave rise to stable, settled societies, which enjoyed considerable prosperity. Settled circumstances and a certain amount of leisure made the accumulation and spread of knowledge easier. Sustained farming prepared the way for urban life.