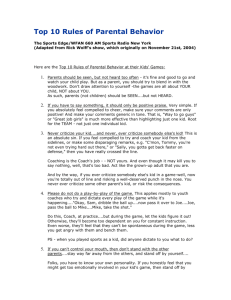

Graduating (from the business of youth sports) Thirty million kids

advertisement

Graduating (from the business of youth sports) Thirty million kids play in youth league sports in this country. When 30 million people do any one thing, that one thing soon becomes big business. In the past 15 years, there has been an explosion of club teams, private coaching, strength and conditioning gyms, sport-specific camps, and any other pay-to-play endeavor to capture this market. Winter indoor leagues for warm weather sports. Offseason leagues. Year-round this, year-round that. It is all designed to help kids become high school stars and -- the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow -- help them get college scholarships. Thirty million kids play, but for a healthy slice of that number, it becomes work. This is the story of one of them. For years, the father told his kid's story as a cautionary tale about youth sports burnout. The kid was a natural. The minute she picked up a field hockey stick, she loved the game, and it loved her back. She ran the field with colts' legs and ponytail flying. When she got where she was going, good things happened. In her first season in middle school, she was leading scorer, then came back and did it again. Her high school team was a perennial state power, but the kid played a little varsity by sophomore year. Senior year, she was captain, and once hit the ball so hard during a game, it broke in half. Everybody froze as the refs tried to figure what to do. After her freshman year she joined a private club. The coach was a former Olympian, from a South Asian country where men play field hockey. She became a better player, yes, but the schedule was nonstop. There were weekend tournaments in places like Virginia Beach and Scranton. For eight hours a day over two days, the girls would play a 20-minute game, and then have the next 20 minutes off. All day like that. By the end of the day, the girls were spending their 20 minutes off massaging their sore feet. There were national tournaments in California and Florida. There were programs called "Futures" that promised "Olympic development." The team traveled to Holland one summer. Good experiences, yes. But an awful lot of field hockey. But that's what she wanted: to concentrate on her sport. How can a parent say no? How can you derail a kid's dreams? That's where they get you. That's why youth sports has become such a big business. While the kid played, the father saw how a kid's sport can cannibalize family life. Dinnertimes on the bleachers, instead of at the table. Sunday mornings on the bleachers, instead of in church. Families packing up like nomads, wandering the landscape of youth sports, going off distant cities for weekend tournaments, living out of hotels, eating out of fast-food bags, caddying their little stars' equipment bags. The kid got her scholarship. She went D-1, as they say in jock circles. Better yet, she was red-shirted as a freshman, meaning the Maryland university that signed her was willing to give her five years of education. As long as she played. But when the kid got to college she learned the truth. She wasn't there to be a college student; she was there to be a field hockey player. Year-round. Early A.M. workouts, afternoon sessions. Lifting and running came before learning and studying. Classes were what you did when you weren't with the team. The father went down for a game during her freshman year, even though he knew she wasn't playing. At the end of the game, there was a team tailgate. The hover parents were there with their flowers, balloons and casseroles and sandwiches. When the kid came out of the locker room, the father saw it on her face. This wasn't college. This was an extension of high school. "She's done," the father thought. The next spring, she made it official. "Dad, I don't want to play anymore," she said. Too much sport, and not enough school. And she loved the school. But the free ride was over. What happened next was this: the kid who grew out of her sport and grew into adulthood. She made up the scholarship money by working as a waitress. First at a crummy chain, then graduating to finer restaurants. She got her in-state residency after a year of showing income and a permanent state address. She did this by signing a townhouse lease then finding roommates to fill it up. There were bumps along the way. Work was exhausting. She got stiffed on the rent by one deadbeat. All in all, it was probably harder than playing. But it got her ready for the world outside the lines. Long story short, the kid graduates this week with a degree in economics. The story has gone from a cautionary tale to one of success. She attacked school the way she played, and now graduate school awaits, paid for by a teaching assistantship. The kid, my oldest daughter, is already thinking Ph.D. Of course, some of these life lessons she learned from playing sports. But most she learned from living life off the playing field, where winning and losing isn't black-andwhite, and where the game is not packaged in manageable time slots, but comes at you relentlessly and unexpectedly.