Moral Assessment

advertisement

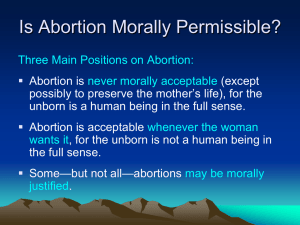

MORAL ASSESSMENT 1. Morally Assessing Actions - - - An action is morally desirable just in case it is especially morally good and morally undesirable just in case it is especially morally bad. An action is morally permissible just in case it violates no moral requirement. (Some permissible actions may be morally undesirable.) o An option is morally obligatory (alternatively: justice-obligatory) just in case it is permissible (just) and no feasible alternative is. o An option is morally optional (alternatively: justice-optional) just in case it is permissible (just) and some feasible alternative is also. Optional actions may be subdivided as follows: recommended (desirable)= significantly morally better than the worst optional action and not significantly worse than the best optional action o If it involves significant sacrifice by the agent relative to his prudentially best optional action, then it is supererogatory. indifferent = either (1) significantly morally better than the worst optional action and significantly worse than the best optional action, or (2) neither of these (in which case the best and worst are close together). discouraged (undesirable) = not significantly morally better than the worst optional action and significantly worse than the best optional action o If it involves no significant sacrifice by the agent relative to his prudentially best optional action, then it is suberogatory. An action is morally just (in one sense) just in case it infringes no one’s rights. (Some just actions may be morally wrong because they violate an impersonal duty or because they have sufficiently bad results for individuals. Some unjust actions may be permissible because they have sufficiently better results for individuals.) An action is morally legitimate just in case others are not permitted to interfere forcibly with the action—either because it’s permissible or because it’s non-enforceably impermissible. o Note: Some impermissible (e.g., unjust) actions may not be enforceable because the harm involved is not significant enough to justify forcible interference. Also, even an impersonal duty may be enforceable. Enforceable duties thus need not be limited to duties of justice. o “Legitimacy” is used in many different senses, and this is but one of them. Enforceably impermissible -> impermissible -> undesirable (but not in other direction). Objective (external) vs. Subjective (internal) Assessment: An action or agent can be assessed on the basis of the objective facts about actions performed (objective assessment) or on the basis of the agent’s beliefs (or perhaps intentions) about the actions performed. Thus, an action might be objectively permissible by subjectively impermissible. My view is that the most basic assessment of actions is the objective assessment, and that for the purposes of blame and praise of actions, or of agents, some kind of subjective assessment is appropriate. A common objective way of assessing the justice of agents (or organizations, such as the state) is to judge that the agent is (e.g.) just if and only if his/her actions are typically just. The qualification “at least typically” is used here so that occasional failures do not automatically make, for example, an agent unjust (even though it makes him/her less than perfectly just). (This is like assessing the justice of an agent’s character, except that it considers only past actions, and not the disposition for future action.) 2. The Meaning of “Justice” Although I use “justice” in the sense of not violating anyone’s rights, it is used in several different senses by others. Here are some of the main uses: - Justice as moral permissibility of social structures (e.g., laws). - Justice as fairness (roughly: comparative desert; it is but one consideration for moral permissibility; efficiency and liberty may be others). - Justice as satisfying the duties we owe each other (including ourselves) [i.e., as what people have a right to]: This is silent about impersonal duties (owed to no one). - Justice as satisfying the duties we owe others: This is silent about impersonal duties (owed to no one) and duties to self. - Justice as satisfying the enforceable duties that we have (or more narrowly: owe others): This is silent about duties that are not permissibly enforceable. (Just acts are those that are morally permissible or that are impermissible but not enforceable.) There are two main views about how the justice of actions and the justice of social structures are related. On one view, the justice of actions is assessed directly, and a social structure is just if and only if it forbids all and only unjust actions. On the other view, the justice of social structures is assessed directly, and an action is just if and only if it is permitted by a just social structure. 3. Theories of Justice Two definitions of terms used below: An option is Pareto optimal just in case no feasible alternative makes someone better off and no one worse off. This is a weak efficiency condition. It does not require that total wellbeing (or benefits) be maximized. Indeed, it does not make any interpersonal comparisons of wellbeing. Example with two people: <2,2> vs. <2,3> vs. <1,9>. The first is not Pareto optimal, but the latter two are. An option leximins (short for lexically maximizes the minimum) wellbeing just in case, relative to the feasible options (1) it maximizes the wellbeing of the worst off position, (2) in cases of 2 ties, maximizes the wellbeing of the second worst off position, and so on. Example with two people: <2,2> vs. <2,3> vs. <1,9>. The third option does not maximize the wellbeing of the worst off position, but the first two do. Only the second option leximins wellbeing. Leximin is a kind of prioritarian theory (i.e., a theory that attaches extra moral importance to increasing the benefits of those who are worse off). The following are some standard theories of justice. Note that there are two general approaches: (1) Assessment of actions is primary, and assessment of social structures is derivative (e.g., social structure is just if and only if it permits only just actions). (I favor this approach.) (2) Assessment of social structures is primary and assessment of actions is derivative (e.g., action is just if and only if it conforms to just social structures). 3.1 Theories of the Justice of Actions a. Divine Command Theory: An action is just if and only if it would violate God’s commands for anyone else to coercively prevent the agent from performing it. b. Libertarianism: An action is just if and only if it violates no one’s the libertarian rights (full self-ownership plus specified property rights in external things). c. Act Utilitarianism: An action is just if and only if it would not maximize aggregate utility for anyone else to coercively prevent the agent from performing it. d. Pure Egalitarianism: An action is just if and only if would not maximize equality (of the relevant sort) for anyone else to coercively prevent the agent from performing it. e. Liberal Paretian Egalitarianism: An action is just if and only if (1) it would violate no one’s liberal (e.g., libertarian) rights, (2) relative to those feasible actions that violate no such rights, it is Pareto optimal (see above for definition), and (3) relative to those feasible actions that are Pareto optimal in this manner, it maximizes equality (of the relevant sort). Rawls’s Two Principles of Justice—modified to apply to actions and in some other ways as well— have roughly this form: An action is just if and only if (1) it would violate no one’s right to maximum equal liberty or to fair (merit-based) equality of opportunity for offices and positions, and (2) relative to those feasible actions that violate no such rights, it leximins well-being (see above for definition). f. Rule Contractarianism: An action is just if and only if the rules that the members of society would agree to under free and equal dialogue would not permit anyone to coercively prevent the agent from performing the action. 3.2 Theories of the Justice of Social Structures: a. Divine Command Theory: A social structure is just if and only if it does not permit enforcement by means of actions that violate God’s commands. 3 b. Libertarianism: A social structure is just if and only if it prohibits (all and?) only actions that violate someone’s libertarian rights (full self-ownership plus property rights in external things). c. Utilitarianism: A social structure is just if and only if its adoption would maximize aggregate utility. d. Pure Egalitarianism: A social structure is just if and only if its adoption would maximize equality (of the relevant sort). e. Liberal Paretian Egalitarianism: A social structure is just if and only if (1) it prohibits the violation of specified liberal (e.g., libertarian) rights, (2) relative to those feasible social structures that so prohibit, it is Pareto optimal, and (3) relative to those feasible social structures are Pareto in this manner, it maximizes equality (of the relevant sort). Rawls’s Two Principles of Justice—modified certain ways—have roughly this form: A social structure is just if and only if (1) it prohibits all actions that would violate someone’s right to maximum equal liberty or to fair (merit-based) equality of opportunity for offices and positions, and (2) relative to those feasible social structures that prohibit all such actions, it leximins well-being. f. Contractarianism: A social structure is just if and only if the members of society would agree to its terms under free and equal dialogue. 4. Criteria for assessing moral theories: (1) Does it ensure that agents have enough moral liberty (with a wide array of their options being permissible or just)? (2) Does it ensure that agents have enough basic moral protection against being abused (e.g., it being impermissible or unjust for others to torture, assault, or kill them)? (3) Does it ensure that people’s well-being is efficiently promoted (Pareto optimality)? (4) Does it ensure that equality of opportunity is adequately promoted in the relevant sense? (5) Does it ensure that people are adequately accountable for their past actions (wrong-doings, commitments, etc.)? (6) Other considerations? 4