Intro - Oregon State University

advertisement

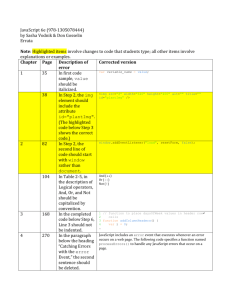

Knaus, Cronn and Liston 1 1 Knaus et al. 2 A fistful of Astragalus 3 4 5 6 7 8 A fistful of Astragalus: the morphometric architecture of an infra-specific group.1 9 Brian J. Knaus2, 4 10 Rich Cronn3 11 Aaron Liston2 12 13 14 Knaus, Cronn and Liston 2 15 1 Manuscript received _______; revision accepted _______. 16 2 Department of Botany and Plant Pathaology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 17 USA. 18 3 19 OR 97331 USA. 20 4 Pacific Northwest Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 3200 SW Jefferson Way, Corvallis, Author for correspondence (e-mail: knausb@science.oregonstate.edu). 21 22 BJK thanks Richard Halse (OSC) for arranging herbarium loans and support in the herbarium. 23 Nancy Mandel and Randy Johnson (USDA FS, PNW) provided help with statistical analyses. 24 Peter Dolan (OSU) helped fit sine waves to monthly data. Chris Poklemba (USDA FS, PNW) 25 helped with propagation of A. lentiginosus at the Corvallis FSL. Dana York, Kathy Davis, Dell 26 Heter, and Patrick and Christine Whitmarsh provided inspiration, locality information, and 27 housing during collections. Lisa Graumlich (Montana State University), John King (Lone Pine 28 Research, MT), Mark Fishbein (Portland State University), Lucinda McDade (Rancho Santa Ana 29 Botanical Garden), Constance Millar and Bob Westfall (USDA FS, PSW) provided inspiration to 30 BJK to pursue this study as a graduate program. The title is a tribute to Rupert Barneby who 31 titled a series of his papers “Pugillus Astragalorum.” 32 Grants!!! NPSO, NNPS, Hardman Award Knaus, Cronn and Liston 3 33 ABSTRACT 34 The study of infra-taxa has historically been considered the study of incipient species. The 35 species Astragalus lentiginosus (Fabaceae) is the most taxonomically complex species in the 36 United States flora. The implausible amount of diversity within A. lentiginosus is reflected by its 37 taxonomic history. Morphometric data presented here indicate that the varieties lack clear 38 regions of distinction, which is congruent with their circumscription as infra-taxa. Significant 39 correlations to climatic parameters suggest that the great diversity within A. lentiginosus may be 40 due to local adaptation. Existing infra-specific circumscription is surprisingly similar to 41 statistical optimization. K-means clustering was employed to determine the number of groups 42 but failed to result in an optimal number of groups, suggesting that the varieties are clinal and 43 can be divided into an arbitrary number of infra-taxa. The bewildering amount of diversity 44 contained within the species Astragalus lentiginosus begs for decomposition yet its clinal nature 45 precludes it from division into discrete groups. The use of infra-taxa in this species appears 46 useful in that it divides this bewildering diversity, however there does not appear to be an 47 optimal method based on morphology to decompose this species. Varieties of A. lentiginosus are 48 interpreted as important documentation of infraspecific diversity, however the authors wish to 49 stress that these groups should be interpreted as clinal in nature and not discrete. 50 51 Keywords: Astragalus; clines; Fabaceae; Great Basin; Mojave Desert; morphometrics; 52 speciation. 53 (up to 8) 54 Knaus, Cronn and Liston 4 55 INTRODUCTION 56 The ‘species’ is considered the fundamental unit of biology (Stebbins, 1950; Mayr and Ashlock, 57 1969; Raven and Johnson, 2002; Coyne and Orr, 2004); but see (Bachmann, 1998) Campbell 58 and Reese, 200X. While the PLANTS database of United States plants (USDA, 2006) includes 59 33,383 species it also includes 3,853 taxa at infraspecific ranks (table 1), indicating that around 60 11% of the species in the United States flora include infra-specifics (taxa recognized at the ranks 61 of subspecies or variety). If the species is the fundamental unit of biology then of what value is 62 the infra-specific rank and why do we have so many of them? 63 64 A unifying theme among species concepts is that the species is somehow ‘discrete’ (Mayden, 65 1997; Coyne and Orr, 2004) even though the metric is debatable (e.g., significant morphological 66 distinctiveness, reproductive isolation, reciprocal monophyly, etc.). For example, the Biological 67 Species Concept (Mayr and Ashlock, 1969) indicates that a species is a group of entities that are 68 reproductively isolated from other ‘species.’ This is philosophically attractive because it implies 69 that these entities (the species) no longer share a common evolutionary path due to an inability to 70 share genetic material. However, theory indicates that adaptive divergence, another important 71 concept in evolutionary biology, can occur in spite of gene flow (Wu, 2001; Via, 2002). This 72 indicates that ‘groups’ of organisms can diverge to occupy different adaptive peaks while 73 reproductive barriers may be incomplete or nonexistent. Therefore an important ‘unit’ of 74 evolution may not necessarily require reproductive isolation. However, as long as the transfer of 75 genetic material is possible, there is the possibility of intermediates which may represent poorly 76 adapted individuals or individuals that are adapted to selective forces that are intermediate to the Knaus, Cronn and Liston 5 77 ends of the spectrum. We believe Infra-taxa may represent these entities which represent 78 intermediates along a continuum that is too great to be considered as one. 79 80 If a species this is discrete than how does one delineate infraspecies, which therefore must be 81 somehow non-discrete? Here we employ the most taxonomically complicated species in the 82 United States Flora, Astragalus lentiginosus Dougl. ex Hook. (Fabaceae; USDA, NRCS 2007, 83 table 1), to explore the value and delineation of infraspecies. 84 85 A Brief History of Infra-Taxa— Linnaeus is credited with providing the modern system 86 of binomenal nomenclature however he also employed the trinomial at the rank of ‘variety’ 87 (Linnaeus, 1753). Linnaeus considered the species to be the product of creation while the variety 88 to be variation that has arisen since the creation (Stearn, 1957). Modern nomenclature has 89 adapted an evolutionary system, however, the systems share the concept that infraspecies are 90 recently derived. 91 92 One path to speciation described by Darwin (Darwin, 1859) is the increase in variation to a point 93 where the magnitude of variation is no longer maintainable, resulting in divergence that ends in 94 distinct species. Subsequently he relied on the multitude of artificial selection experiments 95 performed informally by breeders (Darwin, 18??; animals under domestication) to demonstrate 96 this increase in variation, and how this variation can accumulate in a relatively short amount of 97 time. These ideas were somewhat formalized by Fisher (Fisher, 1958) who described the idea of 98 ‘steady states’ and their maintenance, which would break down at large magnitudes. 99 Knaus, Cronn and Liston 6 100 A slightly different perspective was presented by Huxley (Huxley, 1938, 1939) through the study 101 of clines. Huxley addressed the study of large amounts of discontinuous variation and sought to 102 classify it. Huxley tried to decompose the problem of clines, in part, by proposing the idea of 103 stepped clines, clines in which different groups possess a shallower slope than the entire group. 104 This usually requires the a priori determination of groups, a move that is as contentious as the 105 argument between lumpers and splitters. 106 107 Wilson and Brown (Wilson and Brown, 1953) criticized the subspecific rank. Among their 108 points were that the naming of these groups detracted attention from the species and implied a 109 discrete nature to these infraspecific groups. This is misleading because it is the ‘species’ that is 110 supposedly discrete. This leaves the subspecies as a group of entities whose divisions appear 111 arbitrary and therefore may have little value. In a rebuttal to these criticisms Mayr (1953) agreed 112 that the infraspecific rank confused the importance of the species (which should be the focus of 113 biology) but defended the infraspecies as an important record of infraspecific diversity. 114 115 The controversy surrounding infraspecies continues in the literature. Perhaps the most recent 116 critic being Zink (Zink, 2004) who presents mitochondrial data as refuting the evolutionary 117 relavence of the infraspecies. A shortcoming of Zink’s argument is that it doesn’t address 118 current research topics such as the coalescence (Hudson, 1991; Nordborg, 2001; Hudson and 119 Coyne, 2002; Roseberg and Nordborg, 2002) or adaptive divergence (Wu, 2001; Via, 2002; 120 Dieckmann et al., 2004). Haig et al. (Haig et al., 2006) have provided a recent review of the 121 infraspecies in the context of the Endangered Species Act and biological conservation. They 122 supported recognition of the infraspecies in part on grounds that in the United States legal Knaus, Cronn and Liston 7 123 protection is applied only to named groups of organisms (particularly in plants) which puts an 124 emphasis on recognizing polymorphism, even if it may be geographical. 125 126 What’s wrong with geographical variation??? 127 128 Much of the theoretical discussion of the speciation process (Hudson, 1991; Nordborg, 2001; 129 Wu, 2001; Roseberg and Nordborg, 2002; Via, 2002; Dieckmann et al., 2004) employs explicitly 130 genetic models of evolution. While the discrete character of molecular genetic data (e.g., A, T, 131 G or C) promises a discrete answer these authors present theoretical rationale for the existence of 132 genetic intermediates. Here we choose to focus on the morphometrics of a varietal complex. 133 The phenotype has many obvious relations to the genotype (Falconer and Mackay, 1996; Waitt 134 and Levin, 1997; Walsh, 2001) and is of great relevance to the species problem (Rieseberg, 135 Wood, and Baack, 2006). The vast majority of plant taxa have been circumscribed based on the 136 Linnaean Species Concept, or Morphological Species Concept (Mayden, 1997), based on its ease 137 of application and relatively long history. The quantification of the morphological aspects of a 138 taxon of evolutionary interest is therefore a logical first step in gaining inference into processes 139 that may be active within the group. 140 141 The Most Taxonomically Complex Species in the United States Flora— Astragalus 142 lentiginosus Dougl. ex Hook. (Fabaceae) is the most taxonomically complex species in the North 143 American Flora (USDA, NRCS, 2007, table 1). The species is distributed throughout the arid 144 regions of western North America (Fig. 1) where it frequently occupies disturbed, saline, or 145 otherwise marginal habitats. Many of the varieties were originally described as species (Hooker, Knaus, Cronn and Liston 8 146 1833; Gray, 1856, 1863; Sheldon, 1894). As collections increased intermediate forms became 147 apparent which led to their reduction as varieties (Jones, 1895, 1923). Rydberg (Rydberg, 148 1929a, b) employed a very different species concept, elevating the varieties of A. lentiginosus to 149 species in the genera Cystium (inflated pods) and Tium (slightly inflated pods). Within the genus 150 Cystium he included the subgenera Lentiginosa ,Coulteriana, and Diphysa which were separated 151 based on inflorescence length, flower size, and flower color. This grouping is no longer formally 152 recognized with a name but is reflected in the modern keys to the group (Barneby, 1964, 1989; 153 Spellenberg, 1993; Isely, 1998; Welsh et al., 2003) which largely follow the treatments of 154 Barneby. Barneby (Barneby, 1945) returned the group to a single species with numerous 155 varieties. Through time several varieties have been reduced to synonymy (Barneby, 1964, 1989) 156 while new varieties have also been described (Barneby, 1977; Welsh, 1981; Welsh and Barneby, 157 1981; Welsh and Atwood, 2001). As many as 40 varieties have been recognized at once 158 (Barneby, 1945; Isely, 1998), currently we recognize 35 (USDA, NRCS, 2007, table 1). 159 160 161 MATERIALS AND METHODS Morphometric measurements— Specimens from major western herbaria were measured 162 including BRY, JEPS, NESH, NY, ORE, OSC, POM, RENO, RM, RSA, UC and WILLU. A 163 goal of 20 specimens, possessing fruit and flower, were attained for the common varieties of A. 164 lentiginosus (table 2). Sampling was focused on the widespread varieties for the practical reason 165 that these taxa have been most abundantly collected. Some endemic taxa only occur at a few 166 localities (e.g., A. l. vars. albifolius, sesquimetralis, and piscinensis). Sampling of endemic taxa, 167 even if there were sufficient specimens, would have confounded the sampling of single 168 populations versus the range of widespread taxa. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 9 169 170 Fourteen linear morphometric characters were chosen from the keys of Barneby (Barneby, 1945, 171 1964, 1989) and measured with a ruler, electronic caliper, or ocular micrometer (table 3). Three 172 measurements were made of each structure whenever possible and a mean of these values was 173 recorded. Measurements were made from different parts of the plant (e.g., different stems or 174 racemes) whenever possible or from different plants when more than one was on a sheet. The 175 fourteen characters were: stem internode length, leaf rachis length, leaf petiole length, leaflet 176 number, leaflet width, leaflet length, peduncle length, floral axis in fruit, keel length, calyx tooth 177 length, calyx tube length, pod length, pod height, pod valve thickness, beak length. 178 179 Assesment of infraspecific structure— All data were examined for univariate normality 180 and heteroscedacity using histograms and scatterplots (using the generic functions ‘hist’ and 181 ‘plot’, R package ‘graphics’)(R Development Core Team, 2007). The characters ‘floral axis in 182 fruit’ and ‘pod valve thickness’ were natural log transformed to improve normality. Principle 183 components analysis was performed (using the function ‘princomp’ in the R package ‘stats’) on a 184 matrix of correlations to explore patterns of structure in the group. Principle components 185 analysis is an eigen analysis used to explore data without the a priori assignment of groups 186 (Everitt, 2005; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). A matrix of correlations was chosen to give each 187 character equal weighting in the analysis. 188 189 Assesment of varieties— Discriminant function analysis was performed (using the 190 function ‘lda’ in the R package ‘MASS’) to explore structure given the a priori grouping as 191 varieties (Barneby, 1964, 1989) both with and without the use of latitude and longitude as Knaus, Cronn and Liston 10 192 additional explanatory variables (fig. 3). All characters were standardized by standard deviations 193 in order to equalize the magnitude of each character. Discriminant function analysis seeks to 194 build multivariate functions that best discriminate among a priori groups (Everitt, 2005; 195 Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). These functions can then be plotted in ordination space. 196 197 In order to asses the optimal number of groups k-means clustering was performed on the data 198 (using the function kmeans in the R package ‘stats’). K-means analysis uses a predefined 199 number of groups and utilizes an optimality criterion to fit the data within these groups (Everitt, 200 2005; Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). A sum of squares can then be calculated to assess the fit. 201 Note that as the number of groups increases the sum of squares is expected to decrease, therefore 202 researchers usually examine plots for a breakpoint in the data where additional groups no longer 203 appear to dramatically decrease the sum of squares. Standardization by standard deviation was 204 performed to equalize the contribution of each trait. In order to explore the sensitivity of the data 205 to the optimality criterion several methods were employed (Hartigan-Wong, Lloyd, Forgy, and 206 MacQueen). 207 208 Phenological standardization— In order to explore climatic trends in morphology the 209 PRISM dataset (Daly et al., 2002) was used. Specimens were assigned a latitude and longitude 210 by referencing label information to a place-name database (topozone.com) or converted from 211 township and range when available this data was available (www.esg.montana.edu/gl/trs- 212 data.html). The spatial join command in ESRI’s ArcView Spatial Analyst (Redlands, California) 213 was used to extract elevation, monthly minimum and maximum temperature and monthly 214 precipitation from the PRISM dataset. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 11 215 216 Units are sort of mixed up, get radians and days straight 217 In order to assign phenologically meaningful data to the monthly PRISM data a sine wave was fit 218 to each specimen’s annual set of monthly data using: y A sin x t 219 220 where y is degrees Celsius, A is [max(temp)-min(temp)]/2 and scales the amplitude of the wave 221 (which in radians has a maximum and minimum amplitude of 1 and -1), x is days from January 222 1, ω is angular frequency and here is set to 1, and t indicates the initial phase where sin(π/2)=1 223 and occurs at 91.25 days. The initial phase was set by averaging the two greatest temperatures 224 and subtracting 91.25. Trigonometric functions were performed in radians and were converted 225 to days (instead of 360 degrees) with radians = days*π/182.5. The fitting of sine waves was 226 performed using the R statistical programming language (R). 227 228 Simple linear regression was performed (using the function ‘lm’ in the R package ‘stats’) using 229 morphological characters as well as principle components as dependent variables and climatic 230 parameters as independent variables to explore the relative importance of climate on 231 morphology. All statistical analyses were performed with R (R Development Core Team, 2007). 232 233 234 RESULTS Summarize!!! 235 Assesment of infraspecific structure— The naming of infraspecific taxa as well as the 236 provision of infraspecific keys implies a discrete nature to these taxa (Wilson & Brown, 1953). 237 This hierarchy also implies a high degree of diagnosability to these taxa. Names and keys have Knaus, Cronn and Liston 12 238 both been applied to the varieties of Astragalus lentiginosus (Jones, 1923; Barneby, 1945, 1964, 239 1989). In order to explore these implications principle component analysis (Fig. 2) and 240 discriminant function analysis (Fig. 3) were performed on taxonomically important characters 241 (table 3). Principal components analysis (Fig. 2) indicates clustering of morphotypes that show 242 cohesiveness to varieties within morpho-space but lack discrete boundaries. Similarily 243 discriminant function analysis (Fig. 3a) shows cohesiveness to varieties but no distinctiveness. 244 These results demonstrate a clinal nature to the varieties. The varieties appear to occupy 245 contiguous ordination space but lack regions of clear distinction. The inclusion of latitude and 246 longitude (Fig. 3b) as explanatory variables reveales an increase in structure. This demonstrates 247 that a lack of morphometric clustering can be improved by the knowledge of geographic 248 position, indicating that the varieties of A. lentiginosus are geographic races. This is intuitive as 249 botanists viewing herbarium specimens usually look for label information, and frequently curse 250 the collector whom omits locality information. 251 252 Optimal number of groups— In order to asses the optimal number of groups within this 253 species, and thus the number of infraspecific taxa, k-means clustering was performed (Fig. 4). It 254 is important to note that as the number of groups increases the sum of squares is expected to 255 decrease. Researchers are expected to look for a ‘break point’ where inclusion of another group 256 does not dramatically decrease the within group sum of squares. There does not appear to be a 257 ‘natural’ break point in the data (Fig. 4). This indicates that no clear subdivisions exist within 258 the excessive amount of diversity contained within this group. The subgenera of Rydberg (1929) 259 and the varieties of Barneby (1964) are included for comparison. These data indicate that the 260 inclusion of more subgroups decreases the within group sum of squares but does not demonstrate Knaus, Cronn and Liston 13 261 a ‘break point’ where the inclusion of another group does not dramatically decrease the within 262 group sum of squares. This indicates that there are not any ‘natural’ break points within A. 263 lentiginosus. The varieties of A. lentiginosus largely occupy different regions of ordination 264 space, but do not occupy discrete regions of ordination space. This is congruent with current 265 understanding of infraspecies. 266 267 Climatic correlations— In order to explore climatic correlations principle components 268 were compared to climatic parameters. Principle component one is loaded with vegetative 269 characters (table 4.) and is highly negatively correlated with dormant season precipitation (Fig. 270 5a; R2 = 38.38%, p < 2.2 * 10-16). Principle component two is loaded with floral characters 271 (table 4.) and is highly correlated with growing season temperature (Fig. 5b. R2 = 20.9%, p = 272 1.082 * 10-10). These statistics imply a significant and dramatic proportion of the variation in 273 multivariate diversity to be attributable to climatic factors. While the present study design 274 cannot disentangle the relationship between correlation and causation it is nevertheless very 275 intriguing that these correlations are so significant and account for a moderate amount of the 276 variation in these traits. Meta-analyses (Waitt and Levin, 1997) seem to suggest that the 277 correlations may be improved upon if the environmental component of the phenotype is 278 controlled for. 279 280 281 282 283 DISCUSSION Summarize!!! The importance of the morphological species concept— We have chosen to focus on the morphological species concept for largely practical reasons, mainly, its ease of application to Knaus, Cronn and Liston 14 284 herbarium specimens. Evolutionary biologists frequently refer to the Biological Species Concept 285 (Mayr and Ashlock, 1969; Coyne and Orr, 2004) which defines the species as a group of 286 organisms that are reproductively isolated from other species. This is philosophically attractive 287 because it delimits units which can no longer share an evolutionary fate due to their inability to 288 share genetic material. Of the 33,000 species included in the PLANTS database it seems 289 doubtful that a large percentage of the taxa have been subjected to tests of interfertility. 290 Furthermore, the botanical literature includes numerous examples of interfertility among groups 291 which taxonomists have considered to be ‘good’ species (lots of citations). Theory predicts that 292 divergence can progress despite gene flow (Wu, 2001; Via, 2002; Beaumont, 2005). Given the 293 multiple paths to speciation proposed (Dobzhansky, 1951; Grant, 1981; Coyne and Orr, 2004) it 294 seems reasonable to accept a plurality in species concepts (Mayden, 1997). Selection acts on the 295 phenotype so here we have chosen to explore phenotypic divergence within A. lentiginosis, a 296 process that may exceed that of reproductive divergence (Wilding, Butlin, and Grahame, 2001; 297 Beaumont, 2005) (Qst Fst refs). 298 299 Infraspecific structure— The naming of infraspecific taxa and the provision of keys 300 implies a discrete nature to infraspecies (Wilson and Brown, 1953). This is in conflict with the 301 idea of the species as the fundamental unit of biology, where the ‘species’ is considered discrete. 302 Here we’ve demonstrated that the varietal complex Astragalus lentiginosus does not contain 303 ‘discrete’ varieties. Instead, these taxa occupy cohesive regions of ordination space but lack 304 clear or ‘natural’ breaks. The varieties of A. lentiginosus fall along a cline of morphometric 305 diversity. This is consistent within the hierarchical system of nomenclature where the 306 infraspecies (e.g., subspecies or variety) is subordinate to the species. Within this system the Knaus, Cronn and Liston 15 307 ‘species’ is considered ‘discrete’ while subdivisions of this category must necessarily be non- 308 discrete. This is consistent with the presented data where the varieties of A. lentiginosus are 309 contiguous in morphospace but are not discrete. 310 311 Optimal number of groups— The varieties of A. lentiginosus do not fall into coherent 312 classes. This is consistent with PCA and DFA not finding discrete groups within A. lentiginosus. 313 Instead of falling into easily classified groups the varieties of A. lentiginosus fall into regions of a 314 continuum. The morphometric diversity within this group begs distinction, as its taxonomic 315 history reflects. However, despite this great morphological diversity, the species A. lentiginosus 316 appears to be a cohesive unit, eve if this cohesiveness requires disparate parts of the range in 317 order to explain. 318 319 Comparison of Rydberg’s three sections (Rydberg, 1929a) and Barneby’s 14 varieties (Barneby, 320 1964) Fig. 4) demonstrates a large coherence between existing taxonomy and the presented 321 statistical methodology. While statistical methods do demonstrate an improvement upon existing 322 taxonomy it is unclear how dramatic this improvement is. The delimitations of Rydberg 323 (Rydberg, 1929a) and Barneby (Barneby, 1964) represent close approximations to the presented 324 statistical analysis (Fig. 4.). In the interest of stability in the taxonomic system it seems that any 325 ‘improvement’ on the system needs to address this lack of discrete boundaries and the 326 delimitation of somewhat arbitrary groups. 327 328 The inclusion of several optimality criteria was intended to demonstrate the sensitivity of the 329 data to the optimality criterion, however, this does not address the sensitivity of the data to Knaus, Cronn and Liston 16 330 differing analysis methodologies. The presented data demonstrate a lack of distinctiveness to the 331 varieties, however the varieties do possess 332 333 Climatic correlations— Morphologies of A. lentiginosus have significant correlation to 334 climatic parameters (fig. 4) which suggests causation. Climatic change during the beginning of 335 the Holocene has been implicated in changing the distributions of plants (Hewitt)(Grayson, 336 1993). The distribution of A. lentiginosus includes inland sand dunes, desert seeps, as well as 337 regions such as the Lahontan Basin. These habitats have changed dramatically since the last 338 glacial maximum and have undoubtedly played a role in the evolution of A. lentiginosus. Here 339 we’ve explored the role of climate as a potential selective force that may be responsible for the 340 diversity in morphology currently expressed in A. lentiginosus. 341 342 ‘Auxiliary’ systems of taxonomy— A vocabulary to describe clinal relationships among 343 infrataxa exists as “rassenkreis” (Endler, 1977), clines (Huxley, 1938, 1939) and ecotypes 344 (Clausen, Keck, and Hiesey, 1939). This vocabulary does not appear to have become prevalent 345 in the taxonomic literature, and hasn’t been mentioned in the literature of A. lentiginosus. This 346 may be due to several reasons. Naming implies homogeneity within a group and distinctiveness 347 among groups, this perhaps is reflected in the Linnaean background where the ‘species’ is a 348 product of Creation. Typification reinforces this idea by suggesting that one specimen is 349 representative of an entire taxon. Conversely, there is an insistence from authors such as Mayr 350 (1940) who feel that species are inherently polymorphic and that the ‘species’ should be 351 considered to contain this diversity. This is perhaps an issue of perspective. Organisms which 352 we are unfamiliar with may appear uniform while taxa we are familiar with may appear to host a Knaus, Cronn and Liston 17 353 wealth of diversity. The more we study something the more detail we discover. In A. 354 lentiginosus we make the argument that while morphological diversity appears to be clinal in 355 nature, particularly for taxonomically important characters, this diversity is of a profound range 356 warranting division. Furthermore, division facilitates one of the most basic purposes of 357 nomenclature and assigns names to allow conversation. The keel lengths of varieties of A. 358 lentiginosus range from 7-11 mm, an almost doubling in size. Keel length is not only important 359 taxonomically but may be tied to pollinator success, so this may be a character under relatively 360 strong selection. It would appear implausible to refer to organisms that are erect, tomentose, and 361 purple flowered and prostrate, glabrous, and white flowered by the same name. Therefore we are 362 stuck with the issue of applying names to arbitrary divisions along the cline between these two 363 extremes. 364 365 The problem of ‘groups’— The major problem within A. lentiginosus is the delimitation 366 of groups or statistical ‘factors.’ The ‘species’ may be considered by many to be a ‘natural’ 367 group. Recent empirical and theoretical research has shown this to be an unreasonable manner to 368 group organisms. The geographical ‘population’ has recently been shown to be an untenable 369 ‘group’ to organize organisms based on migration and admixture (Pritchard, Stephens, and 370 Donnelly, 2000; Falush, Stephens, and Pritchard, 2003; Corander and Marttinen, 2006; Falush, 371 Stephens, and Pritchard, 2007). 372 373 Conclusion—Astragalus lentiginosus is the most taxon rich species in the U.S. flora. 374 Taxa have been historically circumscribed to attempt to account for the amazing amount of 375 morphological diversity contained in the group. We present data which demonstrate Knaus, Cronn and Liston 18 376 taxonomically important characters to be clinal in nature indicating that the varieties may be 377 arbitrary divisions along this cline. Climatic correlations suggest that the differences within A. 378 lentiginosus may be climatic which are also correlated with geography. We recognize that 379 despite this clinal nature important infraspecific differences are present. These differences have 380 been demonstrated in the quantitative genetics literature and can be demonstrated in the present 381 dataset. Optimization of the varieties could be performed through various methods, such as 382 division of principle components into equal partitions. Molecular data (Knaus in prep) promises 383 to add alternate perspectives on the evolutionary relationships with this perplexing group. Future 384 studies are encouraged to address the issue of clinality when making nomenclatural decisions. 385 Further research into this perplexing group may provide interesting insights into the evolution of 386 morphological complexity, climatic adaptation and diversification. 387 388 A species is an array of populations that are evolving collectively ((Rieseberg and Burke, 2001; 389 Morjan and Rieseberg, 2004). This collectiveness can be facilitated through some level of gene 390 flow, shared retention of ancestral traits, or homologous responses to selective pressures. This 391 collectiveness most occur despite the pressures of local adaptation (St Clair, Mandel, and Vance- 392 Borland, 2005) and drift. We present the idea that a varietal complex is an array of populations 393 where the processes that promote collective evolution are giving way to more localized 394 processes. The lack of distinctiveness to the varieties of A. lentiginosus are demonstrative of the 395 collective processes that have historically help this group together. Yet the great amount of 396 diversity and climatic correlations suggest the group is beginning to diverge due to local 397 processes. Further research is required to substantiate these claims but the foundations for these Knaus, Cronn and Liston 19 398 claims have been set with this empirical investigation into the phenotypic divergence within this 399 group. 400 Knaus, Cronn and Liston 20 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 LITERATURE CITED BACHMANN, K. 1998. Species as units of diversity: an outdated concept. Theory in Bioscience 117: 213-230. BARNEBY, R. C. 1945. Pugillus Astragalorum IV: the section diplocystium. Leaflets of Western Botany 4: 65-147. ______. 1964. Atlas of North American Astragalus. Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 13: 1-1188. 408 ______. 1977. Dragma hippomanicum III: novitates Californae. Brittonia 29: 376-381. 409 ______. 1989. Fabales: Intermountain Flora. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx. 410 BEAUMONT, M. A. 2005. Adaptation and speciation: what can FST tell us? Trends in Ecology & 411 412 413 414 415 Evolution 20: 435-440. CLAUSEN, J., D. D. KECK, AND W. M. HIESEY. 1939. The concept of species based on experiment. American Journal of Botany 26: 103-106. CORANDER, J., AND P. MARTTINEN. 2006. Bayesian identification of admixture events using multilocus molecular markers. Molecular Ecology 15: 2833-2843. 416 COYNE, J. A., AND H. A. ORR. 2004. Speciation. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass. 417 DALY, C., W. P. GIBSON, G. H. TAYLOR, G. L. JOHNSON, AND P. PASTERIS. 2002. A knowledge- 418 based approach to the statistical mapping of climate. Climate Research 22: 99-113. 419 DARWIN, C. 1859. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation 420 of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. In D.M. Porter and P.W. Graham eds. The 421 Portable Darwin, 1993. Penguin Books. 422 423 DIECKMANN, U., M. DOEBELI, J. A. J. METZ, AND D. TAUTZ. 2004. Adaptive speciation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK ; New York. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 21 424 425 426 427 DOBZHANSKY, T. 1951. Genetics and the Origin of Species. Columbia University Press, New York. ENDLER, J. A. 1977. Geographic Variation, Speciation, and Clines. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. 428 EVERITT, B. 2005. An R and S-plus companion to multivariate analysis. Springer, London. 429 FALCONER, D. S., AND T. F. C. MACKAY. 1996. Introduction to Quantitative Genetics. Pearson. 430 FALUSH, D., M. STEPHENS, AND J. K. PRITCHARD. 2003. Inference of population structure using 431 multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 164: 432 1567-1587. 433 434 ______. 2007. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: dominant markers and null alleles. Molecular Ecology Notes 7: 574-578. 435 FISHER, R. A. 1958. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Dover. 436 GRANT, V. 1981. Plant Speciation. Columbia University Press, New York. 437 GRAY, A. 1856. Astragalus fremontii. In J. Torrey [ed.], Pacific Rail Road Reports, Vol. 4., 438 Report on the Botany of the Expedition, Washington, D.C. 439 ______. 1863. Revision and arrangement (mainly by the fruit) of the North American species of 440 Astragalus and Oxytropis. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 6: 441 188-237. 442 443 444 445 GRAYSON, D. K. 1993. The desert's past: a natural prehistory of the Great Basin. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington. HAIG, S. M., E. BEEVER, S. M. CHAMBERS, H. M. DRAHEIM, B. D. DUGGER, S. DUNHAM, E. ELLIOT-SMITH, F. J., D. C. KESLER, B. J. KNAUS, I. F. LOPES, P. LOSCHL, T. D. MULLINS, Knaus, Cronn and Liston 22 446 AND L. M. SHEFFIELD. 2006. Taxonomic considerations in listing subspecies under the 447 U.S. endangered species act. Conservation Biology. 448 HOOKER, W. J. 1833. Flora Boreali-Americana. Treuttel & Wurtz, London. 449 HUDSON, R. R. 1991. Gene genealogies and the coalescent process. In D. J. Futuyma and J. 450 Antonovics [eds.], Oxford Surveys in Evolutionary Biology, 1-44. Oxford University 451 Press, Oxford, UK. 452 453 HUDSON, R. R., AND J. A. COYNE. 2002. Mathematical consequences of the genealogical species concept. Evolution 56: 1557-1565. 454 HUXLEY, J. 1938. Clines: an auxiliary taxonomic principle. Nature 142: 219-220. 455 ______. 1939. Clines: an auxiliary method in taxonomy. Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde 456 457 458 459 460 (Contributions to Zoology) 27: 491-520. ISELY, D. 1998. Native and Naturalized Leguminosae (Fabaceae) of the United Stated. Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum, Provo, Utah. JONES, M. E. 1895. Contributions to Western Botany. No. 7. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 5: 611-732. 461 ______. 1923. Revision of North American Astragalus, Salt Lake City, Utah. 462 LINNAEUS, C. 1753. Species Plantarum. Facsimile of the first edition with introduction by W.T. 463 Stearn. 1957. The Ray Society, London. 464 MAYDEN, R. L. 1997. A hierarchy of species concepts: the denouement in the saga of the species 465 problem. In H. A. D. a. M. R. W. M.F. Claridge [ed.], Species: The Units of Biodiversity, 466 381-422. Chapman & Hall. 467 MAYR, E., AND P. D. ASHLOCK. 1969. Principles of Systematic Zoology. McGraw-Hill. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 23 468 MORJAN, C. L., AND L. H. RIESEBERG. 2004. How species evolve collectively: implications of 469 gene flow and selection for the spread of advantageous alleles. Molecular Ecology 13: 470 1341-1356. 471 NORDBORG, M. 2001. Coalescent Theory. In D. J. Balding, M. J. Bishop, and C. Cannings [eds.], 472 Handbook of Statistical Genetics, 179-212. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK. 473 474 475 476 PRITCHARD, J. K., M. STEPHENS, AND P. DONNELLY. 2000. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155: 945-959. R DEVELOPMENT CORE TEAM. 2007. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. 477 RAVEN, P. H., AND G. B. JOHNSON. 2002. Biology. McGraw-Hill. 478 RIESEBERG, L. H., AND J. M. BURKE. 2001. The biological reality of species: gene flow, 479 480 481 482 483 selection, and collective evolution. Taxon 50: 47-67. RIESEBERG, L. H., T. E. WOOD, AND E. J. BAACK. 2006. The nature of plant species. Nature 440: 524-527. ROSEBERG, N. A., AND M. NORDBORG. 2002. Genealogical trees, coalescent theory and the analysis of genetic polymorphisms. Nature Reviews: Genetics 3: 380-390. 484 RYDBERG, P. A. 1929a. Astragalanae. North American Flora 24: 251-462. 485 ______. 1929b. Scylla and Charybdis. Proceedings of the International congress of plant 486 487 488 489 490 sciences, Ithica, New York 2: 1539-1551. SHELDON, E. P. 1894. A preliminary list of the North American species of Astragalus. Minnesota Botanical Studies 1: 116-175. SPELLENBERG, R. 1993. Astragalus. In J. C. Hickman [ed.], The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 24 491 492 493 494 495 496 ST CLAIR, J. B., N. L. MANDEL, AND K. W. VANCE-BORLAND. 2005. Genecology of douglas fir in western Oregon and Washington. Annals of Botany 96: 119-1214. STEARN, W. T. 1957. Introduction, Species Plantarum: a Facsimile of the First Edition, 1753. The Ray Society, London. STEBBINS, G. L. J. 1950. Variation and Evolution in Plants. Columbia University Press, New York. 497 TABACHNICK, B. G., AND L. S. FIDELL. 2007. Using Multivariate Statistics. Pearson. 498 USDA, N. 2006. The PLANTS database (http://plants.usda.gov, 11 Nov. 2006). National Plant 499 Data Center, Baton Rogue, LA 70874-4490 USA. 500 VIA, S. 2002. The ecological genetics of speciation. The American Naturalist 159: S1-S7. 501 WAITT, D. E., AND D. A. LEVIN. 1997. Genetic and phenotypic correlations in plants: a 502 503 504 botanical test of Cheverud's conjecture. Heredity 80: 310-319. WALSH, B. 2001. Quantitative genetics in the age of genomics. Theoretical Population Biology 59: 175-184. 505 WELSH, S. L. 1981. New taxa of western plants - in tribute. Brittonia 33: 294-303. 506 WELSH, S. L., AND R. C. BARNEBY. 1981. Astragalus lentiginosus (Fabaceae) revisited - a 507 508 509 510 511 unique new variety. Iselya 2: 1-2. WELSH, S. L., AND N. D. ATWOOD. 2001. New taxa and nomenclatural proposals in miscellaneous families - Utah and Arizona. Rhodora 103: 71-95. WELSH, S. L., N. D. ATWOOD, S. GOODRICH, AND L. C. HIGGINS. 2003. A Utah Flora. Brigham Young University, Provo. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 25 512 WILDING, C. S., R. K. BUTLIN, AND J. GRAHAME. 2001. Differential gene exchange between 513 parapatric morphs of Littorina saxatilis detected using AFLP markers. Journal of 514 Evolutionary Biology 14: 611-619. 515 516 517 518 WILSON, E. O., AND W. L. BROWN. 1953. The subspecies concept and its taxonomic application. Systematic Zoology 2: 97-111. WU, C.-I. 2001. The genic view of the process of speciation. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 14: 851-865. 519 ZINK, R. M. 2004. The role of subspecies in obscuring avian biological diversity and misleading 520 conservation policy. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 271: 561-564. 521 522 523 Knaus, Cronn and Liston 26 524 525 Table 1. Species of North American plants with 10 or more infrataxa (USDA, NRCS, 2007). Family Fabaceae Polygonaceae Asteraceae Asteraceae Malvaceae Polygonaceae Asteraceae Asteraceae Brassicaceae Asteraceae Caryophyllaceae Fabaceae Rosaceae Asteraceae Brassicaceae Fabaceae Onagraceae Polygonaceae Polygonaceae 526 527 528 529 Scientific Name Astragalus lentiginosus Eriogonum umbellatum Ericameria nauseosa Hymenopappus filifolius Sidalcea malviflora Eriogonum nudum Ericameria parryi Eriophyllum lanatum Lepidium montanum Achillea millefolium Arenaria congesta Trifolium longipes Potentilla glandulosa Machaeranthera canescens Descurainia pinnata Oxytropis campestris Camissonia claviformis Eriogonum heermannii Eriogonum ovalifolium Infra-rank var. var. ssp. & var. var. ssp. var. var. var. var. var. var. ssp. ssp. ssp. & var. ssp. var. ssp. var. var. count 35 30 22 13 13 13 12 12 12 11 11 11 11 10 10 10 10 10 10 Note: There are 33,383 species in the PLANTS database, 1,330 subspecies, and 2,523 varieties. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 27 530 531 532 Table 2. The varieties of Astragalus lentiginosus (USDA, NRCS, 2007), sampled taxa are in bold. Variety A. l. var. australis A. l. var. borreganus A. l. var. kennedyi A. l. var. nigricalycis A. l. var. palansb A. l. var. variabilis A. l. var. ambiguus A. l. var. coachellae A. l. var. maricopae A. l. var. micans A. l. var. stramineus A. l. var. vitreus A. l. var. yuccanus A. l. var. araneosusc A. l. var. chartaceus A. l. var. diphysus A. l. var. higginsii A. l. var. idriensis A. l. var. latus A. l. var. oropedii A. l. var. piscinensis A. l. var. pohlii A. l. var. sesquimetralis A. l. var. wilsonii A. l. var. floribundus A. l. var. fremontii A. l. var. ineptus A. l. var. lentiginosus A. l. var. salinus A. l. var. albifolius A. l. var. antonius A. l. var. kernensis A. l. var. scorpionis A. l. var. semotus A. l. var. sierrae A.l. var. trumbellensis 36 varieties 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 Section Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Coulteriana Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Diphysa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Lentiginosa Distribution widespread widespread widespread widespread widespread widespread endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic widespread widespread widespread endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic widespread widespread widespread widespread widespread endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic endemic Barneby's Samplea 31 31 31 56 40 114 4 34 5 5 9 16 16 39 55 66 NA 24 5 7 NA NA 1 16 26 101 23 73 80 16 8 8 26 14 18 NA 998 Barneby's Specimensa 5 4 3 2 9 9 1 2 0 0 1 2 3 8 8 10 NA 1 1 0 NA NA 0 2 2 14 2 3 10 3 0 0 1 0 2 NA 108 Current Sample NA 19 19 NA 20 21 NA 20 NA NA NA NA NA 20 10 16 NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA 14 21 21 13 20 NA NA NA 10 NA NA NA 244 Notes: This study includes 14 varieties. a Barneby (1964) reports the number of specimens he viewed in preparation of his monograph as well as the number of specimens that were his own collections. Barneby is known for his attention to detail, many of his own collections include drawings with measurements of key characters. We believe these personal collections may represent the sample from which he Knaus, Cronn and Liston 28 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 reports measurements in his monograph as opposed to the multitude which he may have only viewed. b Rydberg (1929) placed many of what is currently known as A. lentiginosus in the two genera Cystium and Tium. Here we have assigned A. l. var. palans to a section of Cystium in order to treat A. lentiginosus as a group. c The variety araneosus is considered a synonym to var. diphysus in Barneby 1989 and the PLANTS database, but was considered a valid taxon in Barneby 1964, the last comprehensive treatment of A. lentiginosus. d Several varieties have been described since Rydberg’s 1929 treatment. Here we’ve taken liberty to place these taxa as we feel Rydberg would have. Knaus, Cronn and Liston 29 554 555 Table 3. Characters measured from specimens of Astragalus lentiginosus. Character Floral peduncle length Fl axis in fruit keel length(mm) calyx tooth length calyx tube length Fruit pod length pod height pod valve thickness beak length Vegetative Stem internode length Leaf rachis length Leaf petiole length Leaflet number Leaflet width Leaflet length 556 557 558 Units Transformation 0.5 mm 0.5 mm 0.5 mm 0.5 mm 0.5 mm Na Ln Na Na Na 0.5 mm 0.5 mm 0.01 mm 0.5 mm Na Na Ln Na 0.5 mm 0.5 mm 0.5 mm n 0.5 mm 0.5 mm Na Na Na Na Na Na Knaus, Cronn and Liston 30 559 Table 4. Loadings on the first five principle components. PC 1 Peduncle_length Fl_axis_in_fruit Keel_length.mm. Pod_length Pod_height Pod_valve_thickness Beak_length Calyx_tooth_length Calyx_tube_length Stem_internode_length Leaf_rachis_length Leaf_petiole_length Leaflet_number Leaflet_width Leaflet_length 560 0.3658 0.2937 0.2956 0.2543 0.0993 0.0866 0.0663 0.2741 0.2577 0.3047 0.3683 0.0242 0.0850 0.3381 0.3375 PC 2 PC 3 PC 4 PC 5 0.2069 0.3250 -0.3821 -0.2265 0.0835 -0.1807 -0.2751 -0.3029 -0.4654 0.2498 0.1681 0.0828 -0.2800 0.1692 0.1614 0.0409 0.0267 0.2145 -0.3597 -0.5256 0.4458 -0.5270 0.0415 0.0713 -0.0130 0.0536 -0.2333 -0.0470 0.0552 -0.0020 0.1855 0.2569 0.0518 -0.0146 -0.0238 -0.2919 -0.1199 -0.2239 0.0142 0.1416 0.1309 -0.3237 0.6515 -0.3395 -0.2540 0.0599 -0.0601 0.1036 -0.2220 0.0625 -0.0139 -0.2473 -0.0528 0.1306 -0.1239 0.1656 0.8459 0.2710 -0.0358 -0.1211 Knaus, Cronn and Liston 31 561 Fig. 1. Geographic distribution of sampled Astragalus lentiginosus. The distribution of A. 562 lentiginosus is primarily between the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Nevada/Cascade Crest, 563 from British Columbia to Baja California Norte. 564 565 Fig. 2. Discriminant function analysis of morphometric data standardized by standard 566 deviations. Analysis was performed with (a) morphology as well as (b) morphology plus latitude 567 and longitude as explanatory factors of Barneby’s varieties (table 2). Grey scale corresponds to 568 Rydberg’s sections, white = Coulteriana, grey = Diphysa, Black = Lentiginosa. 569 570 Fig. 3. K-means clustering of data standardized by standard deviations. Lines represent the 571 optimality criteria Hartigan-Wong, Lloyd, Forgy, and MacQueen. Sum of squares for Rydberg’s 572 three sections and Barneby’s 14 varieties are provided for comparison. 573 574 Fig. 4. Simple linear regression of principle components one and two of morphometric data 575 against climatic parameters. Grey scale corresponds to Rydberg’s sections, white = Coulteriana, 576 grey = Diphysa, Black = Lentiginosa. PC1 is correlated to dormant season precipitation with R2 577 = 38% (F1, 196 = 123.7, p < 2.2e-16). PC2 is correlated to dormant season precipitation with R2 = 578 21% (F1, 174 = 47.23, p = 1.082e-10). 579 580 Fig. 5. Normal distributions of keel lengths plotted from the mean and variance of each variety 581 sampled (table 2). Using A. l. var. diphysus as a reference (μ = 11.5 mm, σ = 1.4 mm) the keel 582 lengths of A. lentiginosus span just over three standard deviations to A. l. var. lentiginosus (μ = 583 7.1 mm, σ = 0.6 mm).