volunteer - Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum

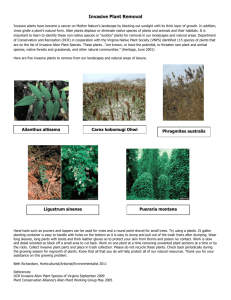

advertisement