Plato v Aristotle - Oxford Books Online

advertisement

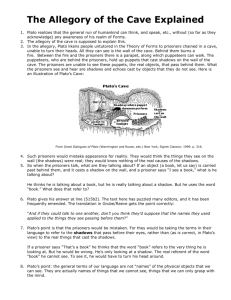

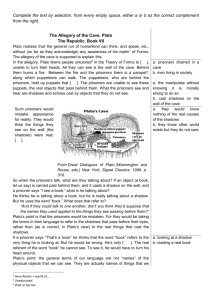

Page 1 of 7 Page 2 of 7 Page 3 of 7 Plato vs. Aristotle - questions 1. Explain Aristotle's Four Causes. 2. Explain Plato's allegory of the cave. 3. Explain Aristotle's concepts of actuality and potentiality. 4. Define 'Actus Purus'. 5. What is empiricism? 6. What is the 'unmoved mover'? 7. Compare and contrast Aristotle's and Plato's views of God. 8. Define Plato's Theory of Forms. 9. Compare and contrast Plato's and Aristotle's influence on Christianity. 10. Where else might you find the concept of a first mover and purpose important? Page 4 of 7 Plato v Aristotle – answers 1. Four causes answers the questions: What is it made of? ; What is its form/essence? ; What made it? ; For what purpose? 2. Here is an excellent step by step explanation, but also add the difficulty of the journey to seek/find the truth once out of the cave: Plato realizes that the general run of humankind can think, and speak, etc., without (so far as they acknowledge) any awareness of his realm of Forms. The allegory of the cave is supposed to explain this. In the allegory, Plato likens people untutored in the Theory of Forms to prisoners chained in a cave, unable to turn their heads. All they can see is the wall of the cave. Behind them burns a fire. Between the fire and the prisoners there is a parapet, along which puppeteers can walk. The puppeteers, who are behind the prisoners, hold up puppets that cast shadows on the wall of the cave. The prisoners are unable to see these puppets, the real objects, that pass behind them. What the prisoners see and hear are shadows and echoes cast by objects that they do not see. Such prisoners would mistake appearance for reality. They would think the things they see on the wall (the shadows) were real; they would know nothing of the real causes of the shadows. So when the prisoners talk, what are they talking about? If an object (a book, let us say) is carried past behind them, and it casts a shadow on the wall, and a prisoner says “I see a book,” what is he talking about? He thinks he is talking about a book, but he is really talking about a shadow. But he uses the word “book.” What does that refer to? Plato gives his answer at line (515b2). The text here has puzzled many editors, and it has been frequently emended. The translation in Grube/Reeve gets the point correctly: “And if they could talk to one another, don’t you think they’d suppose that the names they used applied to the things they see passing before them?” Plato’s point is that the prisoners would be mistaken. For they would be taking the terms in their language to refer to the shadows that pass before their eyes, rather than (as is correct, in Plato’s view) to the real things that cast the shadows. If a prisoner says “That’s a book” he thinks that the word “book” refers to the very thing he is looking at. But he would be wrong. He’s only looking at a shadow. The real referent of the word “book” he cannot see. To see it, he would have to turn his head around. Plato’s point: the general terms of our language are not “names” of the physical objects that we can see. They are actually names of things that we cannot see, things that we can only grasp with the mind. When the prisoners are released, they can turn their heads and see the real objects. Then they realize their error. What can we do that is analogous to turning our heads and seeing the causes of the shadows? We can come to grasp the Forms with our minds. Plato’s aim in the Republic is to describe what is necessary for us to achieve this reflective understanding. But even without it, it remains true that our very ability to think and to speak depends on the Forms. For the terms of the language we use get their meaning by “naming” the Forms that the objects we perceive participate in. The prisoners may learn what a book is by their experience with shadows of books. But they would be mistaken if they thought that the word “book” refers to something that any of them has ever seen. Likewise, we may acquire concepts by our perceptual experience of physical objects. But we would be mistaken if we thought that the concepts that we grasp were on the same level as the things we perceive. Source: http://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/cave.htm Page 5 of 7 3. Potentiality is the capability of the being to realise the fullness of its being; actuality is the fulfilment of that capability. 4. ‘Actus purus’ is perfection – it is complete fulfilment of potentiality, and refers to God, who is infinitely perfect. It is pure actuality. 5. The doctrine that all knowledge is derived from sense experience. 6. The first cause which sets the universe in motion, who is not moved itself and is perfect. 7. And again, see below: To Plato, God is transcendent-the highest and most perfect being-and one who uses eternal forms, or archetypes, to fashion a universe that is eternal and uncreated. The order and purpose he gives the universe is limited by the imperfections inherent in material. Flaws are therefore real and exist in the universe; they are not merely higher divine purposes misunderstood by humans. God is not the author of everything because some things are evil. We can infer that God is the author of the punishments of the wicked because those punishments benefit the wicked. God, being good, is also unchangeable since any change would be for the worse. For Plato, this does not mean (as some later Christian thought held) that God is the ground of moral goodness; rather, whatever is good is good in an of itself. God must be a first cause and a self-moved mover otherwise there will be an infinite regress to causes of causes. Plato is not committed to monotheism, but suggests for example that since planetary motion is uniform and circular, and since such motion is the motion of reason, then a planet must be driven by a rational soul. These souls that drive the planets could be called gods. Aristotle made God passively responsible for change in the world in the sense that all things seek divine perfection. God imbues all things with order and purpose, both of which can be discovered and point to his (or its) divine existence. From those contingent things we come to know universals, whereas God knows universals prior to their existence in things. God, the highest being (though not a loving being), engages in perfect contemplation of the most worthy object, which is himself. He is thus unaware of the world and cares nothing for it, being an unmoved mover. God as pure form is wholly immaterial, and as perfect he is unchanging since he cannot become more perfect. This perfect and immutable God is therefore the apex of being and knowledge. God must be eternal. That is because time is eternal, and since there can be no time without change, change must be eternal. And for change to be eternal the cause of change-the unmoved mover-must also be eternal. To be eternal God must also be immaterial since only immaterial things are immune from change. Additionally, as an immaterial being, God is not extended in space. Source: http://www.iep.utm.edu/g/god-west.htm#SH2a 8. The Theory of Forms states that there is a world inhabited by the real, unchanging, ideal essences/archetypes of all things and ideas that exist. Page 6 of 7 9. This could keep you busy forever: start with their concept of God, their ideas of the soul, their moral philosophy and trace their influences on some of the major theologians: Augustine, Aquinas, etc. Don’t have a heart attack, this is just a question for you to consolidate your knowledge, not a real exam question! 10. Cosmological and design arguments. Further reading: http://www.wisdomworld.org/additional/ancientlandmarks/PlatoAndAristotle.html http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/aristplatoguide/Plato_Aristotle_Study_Guides.htm http://rpp.missouri.edu/disciplines/D28.shtml Page 7 of 7