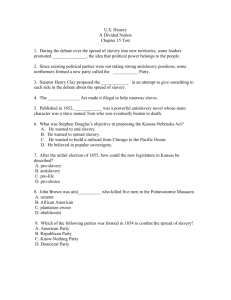

Chapter 11- Sectional Conflict Increases (1845

advertisement

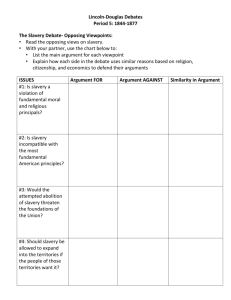

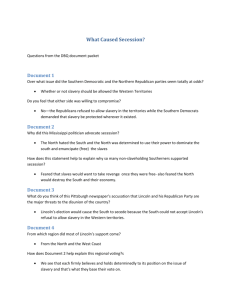

Chapter 11: Sectional Conflict Increases (1845-1861) Section 1: An Uneasy Balance The Debate Reopens The Missouri comprise of 1820 had not ended the debate over the spread of slavery. Congress had admitted Arkansas and Michigan to the Union without dispute in 1836 and 1837, respectively. The balance of power remained the same, however, because Arkansas allowed slavery whereas Michigan did not. Congressional debate dealing with the subject often ended in violence. In 1845, congress not only admitted Texas as a slave state but also added that the state legislature could divide Texas into as many as five states if it wished. The prospect of victory in the Mexican War revived the debate of weather slavery would be allowed in any territory acquired from Mexico. President James Polk and others suggested extending the Missouri Compromise line westward to the Pacific Ocean. Michigan senator Lewis Cass and Illinois senator Stephen Douglas proposed instead that the territories rely on popular sovereignty. Popular sovereignty: Practice of allowing voters in a territory to decide whether to permit slavery there. Neither proposal satisfied those strongly oppose to slavery. The 1848 Election Democrats chose Lewis Cass as their Presidential Candidate. Cass favored popular sovereignty. Whigs nominated Mexican War hero General Zachary Taylor. Taylor held slaves, but did not publicly proclaim himself as pro-slavery. Angered by the reluctance of either party to address the slavery issue, anti-slavery Whigs and Democrats formed the Free-Soil party in August 1848. The Free-Soilers demanded that congress prohibit the expansion of slavery into the territories. The Free-Soil party won enough Democratic votes in the key state of New York to enable the Whig candidate, Taylor, to win the election. Free-Soil candidates also won several seats in the House of Representatives. More important, the presence of the Free-Soil Party showed that politicians could not continue to ignore the slavery question. The Slavery issue in Congress When congress assembled in December 1849, tempers ran high over the slavery issue. Congress was particularly divided over California and New Mexico-the territories of the Mexican cession. California sought to enter the union as a free state. President Taylor urged congress to admit California as a free state. Southern members of congress, however, strongly oppose. The two sides clashed over New Mexico as well. Antislavery members of congress pushed to ban slavery from the territory. Southern member, on the other hand demanded a resolution affirming the right of settlers there to own slaves. Pro-slavery forces called for a tougher fugitive slave law. In 1842 the Supreme Court had ruled that state officials did not have to assist federal officials in capturing runaway slaves. Southern now wanted a law that forced state officials to help with this task. Southern members of Congress also resisted a plan to abolish the slave trade in the District of Columbia and continued to block efforts to prohibit slavery in the territories. Clay’s Proposal Henry Clay proposed admitting California as a free state and abolishing the slave trade not slavery itself- in the District of Colombia. He also advocated paying Texas $10 million to abandon its claim the part of the New Mexican Territory. To persuade southern to accept these terms, Clay suggested that the New Mexico Territory be divided into two territories- New Mexico and Utah- on the basis of popular sovereignty. Finally, he wanted congress to pass a tougher fugitive slave law. This law would force state and local officials as well as private citizens to aid federal officials in the capture and return of escaped slaves. Clay urged lawmakers to put aside their sectional differences and prevent the breakup of the union. Despite his pleas, angry calls from both northern and southern lawmakers supported the end of the union. Most of the northerners who supported the breakup of the Union were abolitionists. The southerners who did so were known as fire-eaters- a group of southern political leaders who held extreme pro-slavery views. Fire-eaters wanted slavery to be protected by federal law or constitutional amendment. The Great Debate in Congress For the next seven months congress heatedly debated Clay’s proposal. One of the bitterest attacks came from John C. Calhoun. Calhoun was the South’s elder statesman and a leading fire-eater with pro-slavery views. He served as a senator, secretary of war, secretary of state, and vice-president. By the 1820s Calhoun was a strong supporter of southern rights. The debates over slavery in the Mexican Cession convinced him that the only adequate guarantee for the South’s rights would be a dual presidency. One president would come from the North and another from the South. By September 1850, congress passed Clay’s measures, known as the Compromise of 1850. Compromise of 1850: Agreement proposed by Henry Clay; allowed California to enter the Union as a free state and divided the rest of the Mexican Cession into two territories where slavery would be decided by popular sovereignty; also settled land claims between Texas and New Mexico, abolished the slave trade in the District of Columbia, and toughened fugitive slave laws. Section 2 Compromise Comes to an End The Early 1850s In the Presidential election of 1852, Democrats united behind Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire, a strong supporter of the Compromise of 1850. Pierce managed to persuade people on both sides of the slavery issue that he shared their views. Some Free-Soilers, convinced that Pierce could hold the South in check, returned to the Democratic Party. Southerners in the meantime generally agreed that Pierce was “sound on all southern questions.” Pierce won the election by a landslide. He called for national harmony and proceeded to appoint a cabinet that included both southerners and northerners. Pierce proved to be a weak leader. He was unable to control his diverse cabinet or to convince northerners that he was not caving in to southern pressure. Many anti-slavery northerners oppose the Compromise of 1850, which authorized the forcible capture of runaway slaves in Free states. Fugitive Slave Act (1850): Law that made it a federal crime to help runaway slaves and allowed for the arrest of escaped slaves even in areas where slavery was illegal. This law met vigorous opposition in the North. Anti-slavery Literature Abolitionist from the North and the Midwest used their pens to win people to their cause. These men and women hoped that their appeals, which were directed at the general public, would be more persuasive than political speeches and maneuverings. In the early 1850s Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel that proved to be particularly significant. Uncle Tom’s Cabin depicted slavery in its many forms, from the harsh sugar plantations to the homes of slaveholders to the plight of runaway slaves. It also showed how slavery broke up African American families. The book struck a chord with many northern readers. It helped justify their feelings that slavery was morally wrong and should be abolished. Although the book sold quickly in the North, southern audience hated it. The novel was banned in many parts of the South, where authors quickly wrote other novels that attempted to defend slavery. The Kansas-Nebraska Act Illinois senator Stephen Douglas was an enthusiastic believer in westward expansion. He declared his support for settlement on the western prairies and construction of a railroad from Chicago, IL to the Pacific Coast. Senator Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854. Kansas Nebraska Act (1854): Law that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska and allowed voters there to choose whether to allow slavery. The Kansas- Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise. It allowed the new states formed from the territories to “be received into the union with or without slavery, as their constitution may prescribe at the time of their admission.” Passage of the act in May 1854 renewed southern hopes of expanding slavery but outraged antislavery northerners. Not everyone opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act solely on abolitionist grounds. Some critics had economic motives. If slavery were allowed to spread to the territories, they argued, it would forced out white workers. These critics reasoned that employers would choose to use slave labor rather than hire wage laborers. “Bleeding Kansas” The Kansas-Nebraska Act pitted antislavery and pro-slavery forces against one another for control of the new territories. To increase the number of antislavery settlers, New Englanders formed the Emigrant Aid Company to help antislavery families move to Kansas. Pro-slavery forces countered by urging southerners to migrate to the new territories. Pro-slavery forces took action in March 1855. As Kansas settlers prepared to elect their first territorial legislation, some 5,000 proslavery Missouri residents crossed into the territory. In Douglas, a town with about 30 residents, more than 200 ballots were cast. The illegal votes cast by the Missouri residents helped elect a pro-slavery legislature in Kansas. The new governing body immediately passed a code making it illegal to criticize slavery. It also banned newspapers that supported Free states, abolitionist journals, and even the sermons of anti-slavery preachers. The antislavery settlers refused to recognize the legitimacy of his new government. They formed the Free State Party and elected their own legislature. As a result, Kansas had two territorial governments one pro-slavery, the other anti-slavery- competing for control. With two rival governments, conflict was inevitable. Proslavery raiders from Missouri attacked antislavery Kansas settlers. They destroyed printing presses and the town library and set fire to the Free State Hotel. In revenge, a group led by abolitionist John Brown attacked a pro-slavery settlement along Pottawatomie Creek. Pottawatomie Massacre (1856): Incident in which a group led by abolitionist John Brown murdered five pro-slavery Kansas. The Pottawatomie Massacre enraged southerners, shocked northerners, and sparked more violence in what newspapers began calling “Bleeding Kansas.” The Republican Party To carry their message to the nation, antislavery voters flocked to a new party gaining power in the north. In 1854 a group of antislavery Whigs and Democrats, together with some Free- Soilers, had organized a party firmly opposed to the expansion of slavery. Reviving the name of Thomas Jefferson’s Party, they called themselves the Republican Party. In Kansas, 1857, voters elected delegates for the territory’s upcoming constitutional convention. Suspecting that pro-slavery forces would rig the elections for delegates to the convention, the antislavery forces boycotted the elections. The constitutional convention, which was thus made up exclusively of proslavery delegates, met at Lecompton, Kansas. Lecompton Constitution (1857): Kansas constitution; gave voters the right to decide whether more slaves could enter the territory, but not whether slavery should exist there. Douglas’s principle of popular sovereignty had been largely discredited because it reflected only pro-slavery views. Section 3 On the Brink of War Dred Scott and the Supreme Court Dred Scott, a slave held by John Emerson. Scott had accompanied Emerson when he served on army posts in the Midwest. In 1846, after Emerson’s death, Scott sued for his freedom. He argued that his prior residence in the free state of Illinois and in the free Wisconsin Territory entitled him to freedom. The Missouri courts had already granted freedom to a number of slaves on similar grounds. In 1856 the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court after moving through the lower courts. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, one of five southerners on the court, wrote the majority opinion against Scott in March 1857. Taney declared that Scott was not a citizen and therefore could not bring suit in U.S. courts. The nation’s founders, Taney asserted, had viewed African Americans as “beings of an inferior order” having “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” He concluded that no African American, slave or free, could ever enjoy the rights of a U.S. citizen. In addition to rejecting Scott’s claim, Taney denied that the federal government had any authority to limit the expansion of slavery. Taney based his decision on the view that the Missouri Compromise had violated the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. This amendment forbids the government to deny anyone’s right to property without “due process of law.” Since slaves were legally classified as property, Taney asserted, Congress had acted unconstitutionally in barring slavery from territory north of the 36’ 30’ latitude. Although Dred Scott and his family were eventually freed by their owners, the Dred Scott decision outraged abolitionists and other opponents of the expansion of slavery. However, many antislavery leaders saw the decision as an opportunity for action. Lincoln and Douglass The year after the Dred Scott decision, a political race in Illinois drew national attention as Republican Abraham Lincoln ran for a seat in the U.S. senate. The conflict over slavery and the Kansas-Nebraska Act prompted Lincoln’s return to politics. In 1858 he ran against Senator Stephen Douglas, who was seeking a third term in the Senate. Douglas was a powerful public speaker and he soon became known as the little Giant. In 1846 Douglass was elected to the senate. As head of the committee on Territories, he helped draft the legislation by which several territories were admitted to the Union. Douglas strongly supported the policy of popular sovereignty. Abraham Lincoln ran against Douglas in the 1858 senatorial elections. Lincoln challenged Douglas to a series of seven debates between August and October 1858. During the debates, Lincoln attacked the Dred Scott decision, which seemed to grant broad constitutional protection to slavery. Like the Republican Party, Lincoln viewed slavery as “a moral, social, and political wrong.” Although he was willing to tolerate slavery in the South, he firmly opposed its expansion in the territories. In a heated debate at Freeport, Illinois, Lincoln challenged Douglas to explain how popular sovereignty was still workable. Douglas replied that the people of a territory could still keep slavery out simply by refusing to pass the local laws necessary to make a slave system work. This agreement, which came to be called the Freeport Doctrine, helped Douglas narrowly defeat Lincoln in the U.S. senate race. Freeport Doctrine (1858): Statement made by Stephen Doulas during the LincolnDouglas debates arguing that people in the territories had the power to ban slavery by refusing to pass laws to protect it. John Brown’s Raid John Brown leader of the 1856 Pottawatomie Massacre again captured the nation’s attention. After fleeing Kansas, Brown made his way east. With money obtained from New England abolitionists, Brown armed a band of some 20 men, including five African Americans. On October 16, 1859, Brown’s small force seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Brown planned to give the arsenal’s guns to slaves living nearby and to establish an independent regime in the southern Appalachian Mountains. He hoped that runaway slaves and free African American would join him in his attempts to liberate slaves form their owners. Brown and his followers easily took possession of the armory and rifle works. However, no slaves came to aid the group. In mid-October feral troops under the command of colonel Robert E. Lee assaulted Brown’s position, killing half of his men and capturing the rest. Brown was convicted of “murder, criminal conspiracy, and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia” and was hanged on December 2, 1859. Six of his followers were later executed. Although some people questioned Brown’s sanity, many of his supporters remained convinced that he had acted justly and heroically. Well-known abolitionists viewed Brown as a great moral figure. In contrast, many southern whites, alarmed by the treat of slave revolts, viewed Brown as a blood thirsty fanatic who deserved his punishment. Many southern secessionists, however, were pleased by the hysteria. They believed that the incident at Harpers Ferry would lead yeoman farmers and poor whites of the south to support the planters cause. The Election of 1860 Southerners nominated Vice-President John Breckinridge for the Presidential election of 1860. Like many other southerners, Breckinridge interpreted the Dred Scott decision to mean that congress had a duty to protect slavery in the territories. The Republican Party nominated Abraham Lincoln, who seemed a more moderate choice than a strong abolitionist. The Republicans design their platform to attract northern industrialists and wage earners as well as Midwestern farmers. The Republicans had little hope for success in the South and in the end did not even campaign in most southern states. Although Lincoln received only about 40 percent of the popular vote, his election victory was a landslide: 180 electoral votes to Breckinridge’s 72. Secession Despite Abraham Lincoln moderate stance on slavery, many southerners viewed his victory as a victory for abolition. Lincoln’s win particularly mobilized the lower South. Within days of the election, the South Carolina legislature called a convention and unanimously voted to leave the Union. Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas soon passed similar acts of secession. Early in 1861, debates from six of the seven seceding states met in Montgomery, Alabama, and drafted a constitution for the Confederate States of America. This new constitution resembled the U.S. Constitution, with two key exceptions: 1) the confederate constitution guaranteed the right to own slaves and 2) it stressed that each state was “sovereign and independent.” The delegates chose Mississippi planter and former U.S. senator and Secretary of War Jefferson Davis as provisional president of the confederacy. As the Union dissolved, outgoing president James Buchanan announced that no state had the right to secede. However, he concluded that the federal government had no power to hold a state in the union against its will. Caught in a dilemma, Buchanan let the incoming president deal with the problem. The southern secessionist justified their position by stating that since individual states had come together to form the union, a state had the right to withdraw from the union. Northerners countered that by ratifying the Constitution, the states had agreed to recognize it as the supreme law of the land. They argued that there could be no nation if a state was free to withdraw anytime it did not like the actions of the federal government or of the majority of states. Also at stake was the determination of the southerners to protect slavery. They feared that restricting slavery in the territories would ensure that the slave states remained a minority voting alliance. Then, eventually, the northern majority in congress would not only prohibit slavery in the territories but also abolish it in the South.