Ohio Civil Rights Commission v. Dayton Christian Schools, Inc., 477

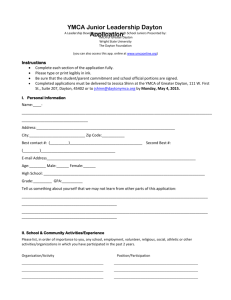

advertisement

100297 Send to: SCHUBMEHL, MEGHAN COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL 435 W 116TH ST NEW YORK, NY 10027-7201 Time of Request: Friday, April 02, 2010 Client ID/Project Name: Number of Lines: 541 Job Number: 2841:213628183 Research Information Service: LEXSEE(R) Feature Print Request: Current Document: 1 Source: Get by LEXSEE(R) Search Terms: 477 U.S. 619 12:51:31 EST Page 1 LEXSEE 477 U.S. 619 OHIO CIVIL RIGHTS COMMISSION ET AL. v. DAYTON CHRISTIAN SCHOOLS, INC., ET AL. No. 85-488 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES 477 U.S. 619; 106 S. Ct. 2718; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71; 54 U.S.L.W. 4860; 41 Fair Empl. Prac. Cas. (BNA) 78; 40 Empl. Prac. Dec. (CCH) P36,195 March 26, 1986, Argued June 27, 1986, Decided PRIOR HISTORY: APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT. DISPOSITION: 766 F.2d 932, reversed and remanded. DECISION: Younger v Harris abstention doctrine held to apply where school brought federal suit to enjoin proceeding by state agency investigating alleged sex discrimination in school's hiring and termination decisions. SUMMARY: A private, nonprofit corporation was formed by two churches in Dayton, Ohio to provide education at elementary and secondary school levels. When a teacher employed by the corporation told her principal that she was pregnant, she was told that her employment contract would not be renewed because of the corporation's religious doctrine that mothers should stay home with their preschool-age children. The teacher filed a complaint with the Ohio Civil Rights Commission, alleging that the nonrenewal decision constituted sex discrimination in violation of an Ohio statute. The corporation terminated the teacher's employment and rejected a proposal by the commission that it reinstate the teacher with backpay, whereupon the commission initiated administrative proceedings against the corporation by filing a complaint. While these proceedings were pending, the corporation filed an action in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio under 42 USCS 1983, seeking a permanent injunction of the state proceedings on the ground that any investigation of its hiring process or any imposition of sanctions for its nonrenewal or termination decisions would violate the religion clauses of the First Amendment. The commission filed a motion to dismiss, arguing that the District Court should refrain from enjoining the administrative proceedings based on federal abstention doctrines. Without addressing the abstention argument, the District Court refused to issue the injunction (578 F Supp 1004). The United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed, holding that the exercise of jurisdiction would violate both the free exercise and establishment of religion clauses of the First Amendment (766 F2d 932). On appeal, the United States Supreme Court reversed and remanded. In Page 2 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 an opinion by Rehnquist, J., joined by Burger, Ch. J., and White, Powell, and O'Connor, JJ., it was held that (1) the Supreme Court had appellate jurisdiction under 28 USCS 1254(2) to review the decision of the Court of Appeals that the Ohio sex discrimination statute, as applied, violated the religion clauses of the First Amendment, (2) the District Court should have abstained, under Younger v Harris, 401 US 37, 27 L Ed 2d 669, 91 S Ct 746, and later cases, from adjudicating the case, since the elimination of prohibited sex discrimination was a sufficiently important state interest to bring the case within the ambit of the Younger abstention principles, and there was no reason to doubt that the corporation would have an adequate opportunity to raise its constitutional claims, either before the Ohio Civil Rights Commission itself or in state court judicial review of the proceeding, and (3) the Ohio Civil Rights Commission did not violate the corporation's First Amendment rights by merely investigating the circumstances of the teacher's discharge. Stevens, J., joined by Brennan, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ., concurred in the judgment, expressing the view that (1) neither the investigation of certain charges by the Civil Rights Commission nor its conduct of a hearing on those charges was prohibited by the First Amendment, and (2) the corporation's constitutional challenge to the remedial provisions of the Ohio statute was not ripe for review, but (3) the Younger abstention doctrine did not require the District Court to dismiss the complaint, since such a disposition would presumably deny the corporation a federal forum to adjudicate the constitutionality of a provisional administrative remedy if the Civil Rights Commission were to impose such a remedy while refusing to address the merits of the corporation's constitutional claims. LAWYERS' EDITION HEADNOTES: [***LEdHN1] APPEAL §254 Supreme Court -- jurisdiction -Headnote:[1A][1B] The United States Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction under 28 USCS 1254(2) to review a decision of a Federal Court of Appeals that a state statute, as applied to authorize a state administrative body to investigate sex discrimination charges against a nonprofit corporation that operates Christian schools and to decide whether to impose sanctions, violates the religion clauses of the First Amendment. [***LEdHN2] COURTS §691 federal abstention -- injunction of state proceedings -Headnote:[2A][2B][2C] A Federal District Court should abstain, under Younger v Harris, 401 US 37, 27 L Ed 2d 669, 91 S Ct 746, and later cases, from adjudicating a case in which a nonprofit corporation that operates Christian schools seeks a permanent injunction of proceedings by a state civil rights commission investigating alleged sex discrimination in the corporation's hiring and termination decisions, where the corporation claims that the religion clauses of the First Amendment prohibit the commission from exercising jurisdiction over it or imposing sanctions on it, but where there is no reason to doubt that the corporation will have an adequate opportunity to raise its constitutional claims, either before the commission itself or in state court judicial review of the proceedings; the elimination of prohibited sex discrimination is a sufficiently important state interest to bring the case within the ambit of the Younger abstention principle. (Stevens, Brennan, Marshall, and Blackmun, JJ., dissented from this holding.) [***LEdHN3] APPEAL §254 Page 3 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 Supreme Court -- jurisdiction -Headnote:[3] Under 28 USCS 1254(2), which authorizes an appeal to the United States Supreme Court by a party relying on a state statute held by a Federal Court of Appeals to be unconstitutional, an appeal is authorized in cases holding a state statute unconstitutional as applied to the facts of the case. [***LEdHN7] CIVIL RIGHTS §30 [***LEdHN4] COURTS §691 COURTS §763 federal abstention -- state administrative proceedings -- exhaustion of remedies -- ripeness -Headnote:[4A][4B] The filing of an administrative action by a state civil rights commission, threatening sanctions against a corporation for allegedly engaging in sex discrimination in its hiring and termination decisions, creates a ripe controversy where the corporation seeks to enjoin the administrative action in a Federal District Court. [***LEdHN5] COURTS §683 federal state -- Ed 2d 669, 91 S Ct 746, holding that federal courts should generally not enjoin state proceedings, have been applied to pending state administrative proceedings in which an important state interest is involved, such abstention may not be appropriate where state law expressly indicates that the administrative proceedings are not judicial in nature. abstention -- waiver by Headnote:[5] A state may voluntarily submit to federal court jurisdiction even though it might have a tenable claim that the court should abstain from exercising its jurisdiction; however, a state does not waive its claim to abstention where it stipulates to the federal court's jurisdiction but does not expressly urge the court to proceed to an adjudication of the merits. [***LEdHN6] COURTS §691 federal abstention proceedings -- -- nonjudicial Headnote:[6A][6B] Although the abstention principles of Younger v Harris, 401 US 37, 27 L Headnote:[7A][7B] The application of the principles of Younger v Harris, 401 US 37, 27 L Ed 2d 669, 91 S Ct 746, holding that federal courts should generally not enjoin state proceedings, to pending state administrative proceedings is consistent with the rule that litigants need not exhaust their administrative remedies prior to bringing suit under 42 USCS 1983 in federal court; federal abstention is proper where the administrative proceedings in question (1) are coercive rather than remedial, (2) begin before any substantial advancement in the federal action takes place, and (3) involve an important state interest. [***LEdHN8] CONSTITUTIONAL LAW §963 schools -- First Amendment -- state investigation -Headnote:[8] A state civil rights commission does not violate the First Amendment rights of a nonprofit corporation that operates Christian schools by exercising jurisdiction over the corporation to investigate the circumstances under which one of its teachers was discharged, if only to ascertain whether the religious-based reason ascribed by the corporation was in fact the reason Page 4 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 for the discharge; religious schools cannot claim to be wholly free from some state regulation. [***LEdHN9] COURTS §691 federal abstention -- pending administrative proceeding -- constitutional objections -Headnote:[9] In order for the abstention principles of Younger v Harris, 401 US 37, 27 L Ed 2d 669, 91 S Ct 746, and later cases to apply to a pending state administrative proceeding in which important state interests are involved, it is sufficient that the party seeking to enjoin the proceeding has the opportunity to raise constitutional claims in state court judicial review of the proceeding; thus, the proceeding of a state civil rights commission affords an adequate opportunity for a target of its investigation to raise constitutional claims against the commission's potential sanctions for alleged sex discrimination where there is no indication that judicial review of the constitutional claims in state court is not authorized by state statute. SYLLABUS Appellee Dayton Christian Schools, Inc. (Dayton), a private nonprofit corporation that provides elementary and secondary education, requires that its teachers subscribe to a particular set of religious beliefs, including belief in the internal resolution of disputes through the "Biblical chain of command." As a contractual condition of employment, teachers must agree to present any grievance to their immediate supervisor and to acquiesce in the final authority of Dayton's board of directors, rather than to pursue a remedy in civil court. After a pregnant teacher was told that her employment contract would not be renewed because of Dayton's religious doctrine that mothers should stay home with their preschool age children, she contacted an attorney, who threatened Dayton with litigation under state and federal sex discrimination laws if it did not agree to rehire the teacher for the coming school year. Dayton then rescinded its nonrenewal decision, but terminated the teacher because of her violation of the internal dispute resolution doctrine. The teacher then filed a charge with appellant Ohio Civil Rights Commission, alleging that under Ohio statutes Dayton's original nonrenewal decision constituted unlawful sex discrimination and its termination decision unlawfully penalized her for asserting her rights. Ultimately, the Commission initiated administrative proceedings against Dayton, which answered the complaint by asserting that the First Amendment prevented the Commission from exercising jurisdiction over it since its actions had been taken pursuant to sincerely held religious beliefs. While the administrative proceedings were pending, Dayton and others (also appellees here) filed this action in Federal District Court, seeking an injunction against the state administrative proceedings on the ground that any investigation of Dayton's hiring process or any imposition of sanctions for its nonrenewal or termination decisions would violate the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment. Without addressing the Commission's argument that the court should abstain from exercising its jurisdiction, the District Court refused to issue an injunction, holding, inter alia, that the Commission's proposed action would not violate the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The Court of Appeals reversed, holding that the Commission's exercise of jurisdiction would violate both the Free Exercise Clause and the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. Held: 1. This Court has appellate jurisdiction over this case under 28 U. S. C. § 1254(2), which authorizes review of a court of appeals' decision holding a state statute unconstitutional as applied to the facts of the case. Page 5 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 Here, the Court of Appeals expressly held that the Ohio statutory provisions relied on by the teacher, as applied to authorize the administrative proceedings, were repugnant to the Religion Clauses. P. 625. 2. The District Court should have abstained from adjudicating this case under Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37, and its progeny. Younger, which held that a federal court should not enjoin a pending state criminal proceeding except when necessary to prevent great and immediate irreparable injury, was based on concerns for comity and federalism. Such concerns are equally applicable to other types of state proceedings, including state administrative proceedings, judicial in nature, in which important state interests are vindicated, so long as in the course of those proceedings the federal plaintiff will have a full and fair opportunity to litigate his constitutional claim. The elimination of prohibited sex discrimination is a sufficiently important state interest to bring the present case within the ambit of the Younger doctrine, and there is no reason to doubt that Dayton will receive an adequate opportunity to raise its constitutional claims. Even assuming that Ohio law is such that the Commission may not consider the constitutionality of the statute under which it operates, it is sufficient that under Ohio law constitutional claims may be raised in state-court judicial review of the administrative proceedings. Pp. 625-629. COUNSEL: Kathleen McManus argued the cause for appellants. With her on the briefs were Anthony J. Celebrezze, Jr., Attorney General of Ohio, and Helen M. Ninos, Assistant Attorney General. William Bentley Ball argued the cause for appellees. With him on the brief were Philip J. Murren, Sandra E. Wise, and Bruce E. Pence. * * Joan E. Bertin, George Kannar, Charles S. Sims, Isabelle Katz Pinzler, and Burt Neuborne filed a brief for the American Civil Liberties Union et al. as amici curiae urging reversal. Briefs of amici curiae urging affirmance were filed for the American Jewish Committee et al. by Kimberlee Wood Colby, Samuel E. Ericsson, Michael J. Woodruff, Samuel Rabinove, and Richard T. Foltin; for Americans United for Separation of Church and State by Lee Boothby and Robert A. Yingst; for the Associated Christian Conciliation Services by John D. Robb; for the Catholic Conference of Ohio by David J. Young; for Concerned Women of America by Diane E. White, Joy R. Powell, and Jordan W. Lorence; for the Council on Religious Freedom by Lee Boothby and Rolland Truman; for the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists by Walter E. Carson and Warren L. Johns; for the Gulf & Great Plains Legal Foundation by Jerald L. Hill and Mark J. Bredemeier; for the National Jewish Commission on Law and Public Affairs ("COLPA") by Daniel D. Chazin, Nathan Lewin, and Dennis Rapps; for the Rutherford Institute et al. by W. Charles Bundren, Guy O. Farley, Jr., John W. Whitehead, D. Kevin Ikenberry, Thomas O. Kotouc, Alfred Lindh, William B. Hollberg, and Wendell R. Bird; and for the United States Catholic Conference by Wilfred R. Caron and Mark E. Chopko. Briefs of amici curiae were filed for the American Jewish Congress by Marc D. Stern and Ronald A. Krauss; and for the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights et al. by Steven Frederick McDowell. JUDGES: REHNQUIST, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which BURGER, C. J., and WHITE, POWELL, and O'CONNOR, JJ., joined. STEVENS, J., filed an opinion concurring in the judgment, Page 6 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 in which BRENNAN, MARSHALL, and BLACKMUN, JJ., joined, post, p. 629. OPINION BY: REHNQUIST OPINION [*621] [***518] [**2720] JUSTICE REHNQUIST delivered the opinion of the Court. [***LEdHR1A] [1A] [***LEdHR2A] [2A]Appellee Dayton Christian Schools, Inc. (Dayton), and various individuals brought an action in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio under 42 U. S. C. § 1983, seeking to enjoin a pending state administrative proceeding brought against Dayton by appellant Ohio Civil Rights Commission (Commission). Dayton asserted that the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses of the First Amendment prohibited the Commission from exercising jurisdiction over it or from punishing it for engaging in employment discrimination. The District Court refused to [*622] issue the injunction on grounds that any conflict between the First Amendment and the administrative proceedings was not yet ripe, and that in any case the proposed action of the Commission violated neither the Free Exercise Clause nor the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, as made applicable to the States by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed, holding that the exercise of jurisdiction and the enforcement of the statute would impermissibly burden appellees' rights under the Free Exercise Clause and would result in excessive entanglement under the Establishment Clause. We postponed the question of jurisdiction pending consideration of the merits. 474 U.S. 978 (1985). We now conclude that we have jurisdiction, and we reverse, holding that the District Court should have abstained under our cases beginning with Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971). Dayton is a private nonprofit corporation that provides education at both the elementary and secondary school levels. It was formed by two local churches, the Patterson Park Brethren Church and the Christian Tabernacle, and it is regarded as a "nondenominational" extension of the Christian education ministries of these two churches. Dayton's corporate charter establishes a board of directors (board) to lead the corporation in both spiritual and temporal matters. App. 11. The charter also includes a section entitled "Statement of Faith," which serves to restrict membership on the board and the educational staff to persons who subscribe to a particular set of religious beliefs. The Statement of Faith requires each board or staff member to be a born-again Christian [***519] and to reaffirm his or her belief annually in the Bible, the Trinity, the nature and mission of Jesus Christ, the doctrine of original sin, the role of the Holy Ghost, the resurrection and judgment of the dead, the need for Christian unity, and the divine creation of human beings. Id., at 5-6. The board has elaborated these requirements to include a belief in the internal resolution of disputes through the "Biblical [*623] chain of command." The core of this doctrine, rooted in passages from the New Testament, is that one Christian should not take another Christian into courts of the State. Teachers are expected to present any grievance they may have to their immediate supervisor, and to acquiesce in the final authority of the board, rather than to pursue a remedy in civil court. The board has sought to ensure compliance with this internal dispute resolution doctrine by making it a contractual condition of employment. Linda Hoskinson was employed as a teacher at Dayton during the 1978-1979 school year. She subscribed to the Statement of Faith and expressly agreed to resolve disputes internally through the Biblical chain of command. In January 1979, she informed her principal, James Rakestraw, that she was pregnant. After consulting with his superiors, Rakestraw informed Page 7 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 Hoskinson that her employment contract would not be renewed at the end of the school year because of Dayton's religious doctrine that mothers should stay home with their preschool age children. Instead of appealing this decision internally, Hoskinson contacted an attorney who [**2721] sent a letter to Dayton's superintendent, Claude Schindler, threatening litigation based on state and federal sex discrimination laws if Dayton did not agree to rehire Hoskinson for the coming school year. Upon receipt of this letter, Schindler informed Hoskinson that she was suspended immediately for challenging the nonrenewal decision in a manner inconsistent with the internal dispute resolution doctrine. The board reviewed this decision and decided to terminate Hoskinson. It stated that the sole reason for her termination was her violation of the internal dispute resolution doctrine, and it rescinded the earlier nonrenewal decision because it said that she had not received adequate prior notice of the doctrine concerning a mother's duty to stay home with her young children. Hoskinson filed a complaint with appellant Ohio Civil Rights Commission (Commission), alleging that Dayton's [*624] nonrenewal decision constituted sex discrimination, in violation of Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 4112.02(A) (Supp. 1985), and that its termination decision penalized her for asserting her rights, in violation of Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 4112.02(I) (Supp. 1985). The Commission notified Dayton that it was conducting a preliminary investigation into the matter, and repeatedly urged Dayton to consider private settlement, warning that failure to do so could result in a formal adjudication of the matter. The Commission eventually determined that there was probable cause to believe that Dayton had discriminated against Hoskinson based on her sex and had retaliated against her for attempting to assert her rights in vio- lation of §§ 4112(A) and (I). Pursuant to Ohio Rev. Code Ann. [***520] § 4112.05(B) (Supp. 1985), it sent Dayton a proposed Conciliation Agreement and Consent Order that would have required Dayton to reinstate Hoskinson with backpay, and would have prohibited Dayton from taking retaliatory action against any employee for participating in the preliminary investigation. The Commission warned Dayton that failure to accede to this proposal or an acceptable counteroffer would result in formal administrative proceedings being initiated against it. When Dayton failed to respond, the Commission initiated administrative proceedings against it by filing a complaint. Dayton answered the complaint by asserting that the First Amendment prevented the Commission from exercising jurisdiction over it since its actions had been taken pursuant to sincerely held religious beliefs. App. 103. While these administrative proceedings were pending, Dayton filed this action against the Commission in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Ohio under 42 U. S. C. § 1983, seeking a permanent injunction against the state proceedings on the ground that any investigation of Dayton's hiring process or any imposition of sanctions for Dayton's nonrenewal or termination decisions would violate [*625] the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment. App. 118-120. The Commission filed a motion to dismiss, arguing, inter alia, that the District Court should refrain from enjoining the administrative proceedings based on federal abstention doctrines. Record, Doc. No. 9, pp. 78. It also filed various documents defending its action on the merits. Without addressing the abstention argument, the District Court refused to issue the injunction. 578 F.Supp. 1004 (1984). The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed, as previously noted, holding that the exercise of such jurisdiction would violate both the Free Exercise Clause and the Page 8 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 Establishment Clause of the Amendment. 766 F.2d 932 (1985). First [***LEdHR1B] [1B] [***LEdHR3] [3]We hold that we have appellate jurisdiction under 28 U. S. C. § 1254(2) to review the decision of the Court of Appeals. That statute authorizes an appeal to this Court "by a party relying on a State statute held by a court of appeals to be invalid as repugnant to the Constitution." This authority embraces cases holding a state statute unconstitutional as applied to the facts of the case. Dutton v. Evans, 400 U.S. 74, 76, n. 6 [**2722] (1970). Here there is no doubt that the decision by the Court of Appeals satisfies this test. The court expressly held that Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 4112.02 et seq. (Supp. 1985) is repugnant to the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses as applied to authorize the administrative body to investigate the charges against Dayton and to decide whether to impose sanctions. See 766 F.2d, at 935, n. 5, 944, 955, 961. [***LEdHR2B] [2B] [***LEdHR4A] [4A] [***LEdHR5] [5]Having taken jurisdiction over the decision below, we now turn to whether the District Court should have exercised jurisdiction over the case itself. We conclude that the District Court should have abstained from adjudicating this case under Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 [***521] (1971), and later cases. 1 The Commission urged such abstention in the District [*626] Court, and on oral argument here. Tr. of Oral Arg. 7-8. Dayton has filed a postargument brief urging that the Commission has waived any claim to abstention because it had stipulated in the District Court that that court had jurisdiction of the action. We think, however, that this argument misconceives the nature of Younger abstention. It does not arise from lack of jurisdiction in the District Court, but from strong policies counseling against the exercise of such jurisdiction where particular kinds of state proceedings have already been commenced. A State may of course voluntarily submit to federal jurisdiction even though it might have had a tenable claim for abstention. See Brown v. Hotel Employees, 468 U.S. 491, 500, n. 9 (1984); Ohio Bureau of Employment Services v. Hodory, 431 U.S. 471, 479-480 (1977); Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393, 396-397, n. 3 (1975). But in each of these cases the State expressly urged this Court or the District Court to proceed to an adjudication of the constitutional merits. We think there was no similar consent or waiver here, and we therefore address the issue of whether the District Court should have abstained from deciding the case. [***LEdHR4B] [4B] 1 We think that any ripeness challenge to appellees' complaint is foreclosed by Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974), and Doran v. Salem Inn, Inc., 422 U.S. 922 (1975). Steffel held that a reasonable threat of prosecution for conduct allegedly protected by the Constitution gives rise to a sufficiently ripe controversy. 415 U.S., at 458460. If a reasonable threat of prosecution creates a ripe controversy, we fail to see how the actual filing of the administrative action threatening sanctions in this case does not. It is true that the administrative body may rule completely or partially in appellees' favor; but it was equally true that the plaintiffs in Steffel and Doran may have prevailed had they in fact been prosecuted. In Younger v. Harris, supra, we held that a federal court should not enjoin a pending state criminal proceeding except in the very unusual situation that an injunction is necessary to prevent great and immediate irreparable injury. We justified our decision both on equitable principles, id., at 43, and on the "more vital consideration" of the proper respect for the fundamental role of States in our federal system. Id., at [*627] Page 9 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 44. Because of our concerns for comity and federalism, we thought that it was "perfectly natural for our cases to repeat time and time again that the normal thing to do when federal courts are asked to enjoin pending proceedings in state courts is not to issue such injunctions." Id., at 45 (emphasis added). [***LEdHR6A] [6A] [***LEdHR7A] [7A]We have since recognized that our concern for comity and federalism is equally applicable to certain other pending state proceedings. We have applied the Younger principle to civil proceedings in which important state interests are involved. Huffman v. Pursue, Ltd., 420 U.S. 592 (1975); Juidice v. Vail, 430 U.S. 327 (1977); Trainor v. Hernandez, 431 U.S. 434 (1977); Moore v. Sims, 442 U.S. 415, 423 (1979). [***522] We have also applied it to state administrative [**2723] proceedings in which important state interests are vindicated, so long as in the course of those proceedings the federal plaintiff would have a full and fair opportunity to litigate his constitutional claim. We stated in Gibson v. Berryhill, 411 U.S. 564, 576-577 (1973), that "administrative proceedings looking toward the revocation of a license to practice medicine may in proper circumstances command the respect due court proceedings." Similarly, we have held that federal courts should refrain from enjoining lawyer disciplinary proceedings initiated by state ethics committees if the proceedings are within the appellate jurisdiction of the appropriate State Supreme Court. Middlesex County Ethics Committee v. Garden State Bar Assn., 457 U.S. 423 (1982). Because we found that the administrative proceedings in Middlesex were "judicial in nature" from the outset, id., at 432-434, it was not essential to the decision that they had progressed to state-court review by the time we heard the federal injunction case. 2 [***LEdHR6B] [6B] [***LEdHR7B] [7B] 2 The lower courts have been virtually uniform in holding that the Younger principle applies to pending state administrative proceedings in which an important state interest is involved. See, e. g., Williams v. Red Bank Board of Education, 662 F.2d 1008 (CA3 1981); Grandco Corp. v. Rochford, 536 F.2d 197, 206 (CA7 1976); McCune v. Frank, 521 F.2d 1152, 1158 (CA2 1975); McDonald v. Metro-North Commuter Railroad Division of Metropolitan Transit Authority, 565 F.Supp. 37 (SDNY 1983) (Weinfeld, J.). Only the recent case of Martori Bros. Distributors v. James-Massengale, 781 F.2d 1349, 1354 (CA9 1986), departs from this position, and it does so without analysis. Of course, if state law expressly indicates that the administrative proceedings are not even "judicial in nature," abstention may not be appropriate. See Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff, 467 U.S. 229, 237-239 (1984).The application of the Younger principle to pending state administrative proceedings is fully consistent with Patsy v. Florida Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496 (1982), which holds that litigants need not exhaust their administrative remedies prior to bringing a § 1983 suit in federal court. Cf. Huffman v. Pursue, Ltd., 420 U.S. 592, 607-611 (1975). Unlike Patsy, the administrative proceedings here are coercive rather than remedial, began before any substantial advancement in the federal action took place, and involve an important state interest. [*628] [***LEdHR2C] [2C] [***LEdHR8] [8]We think the principles enunciated in these cases govern the present one. We have no doubt that the elimination of prohibited sex discrimination is a sufficiently im- Page 10 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 portant state interest to bring the present case within the ambit of the cited authorities. We also have no reason to doubt that Dayton will receive an adequate opportunity to raise its constitutional claims. Dayton contends that the mere exercise of jurisdiction over it by the state administrative body violates its First Amendment rights. But we have repeatedly rejected the argument that a constitutional attack on state procedures themselves "automatically vitiates the adequacy of those procedures for purposes of the Younger-Huffman line of cases." Moore, supra, at 427, n. 10. Even religious schools cannot claim to be wholly free from some state regulation. Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 213 (1972). We therefore think that however Dayton's constitutional claim should be decided on the merits, the Commission violates [***523] no constitutional rights by merely investigating the circumstances of Hoskinson's discharge in this case, if only to ascertain whether the ascribed religious-based reason was in fact the reason for the discharge. the Commission could not construe its own statutory mandate in the light of federal constitutional principles. Cf. NLRB v. Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 440 U.S. 490 (1979). In any event, it is sufficient under Middlesex, supra, at 436, that constitutional claims may be raised in state-court judicial review of the administrative proceeding. Section 4112.06 of Ohio Rev. Code Ann. (1980) provides that any "respondent claiming to be aggrieved by a final order of the commission . . . may obtain judicial review thereof." Dayton cites us to no Ohio authority indicating that this provision does not authorize judicial review of claims that agency action violates the United States Constitution. The judgment of the Court of Appeals is therefore reversed, and the case remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. It is so ordered. CONCUR BY: STEVENS CONCUR [*629] [***LEdHR9] [9]Dayton also contends that the administrative proceedings do not afford the opportunity to level constitutional challenges against the potential sanctions for the alleged sex discrimination. In its reply brief in this Court, the Commission cites several rulings to demonstrate that religious justifications for otherwise illegal conduct are considered by it. See, e. g., In re St. Mary of the Falls, No. 948 (1975). Dayton in turn relies on a decision of the Supreme Court of Ohio, Mobil Oil Corp. v. Rocky River, 38 Ohio St. 2d 23, 26, 309 N. E. 2d 900, 902 [**2724] (1974), in which that court held that a local zoning commission could not consider constitutional claims. But even if Ohio law is such that the Commission may not consider the constitutionality of the statute under which it operates, it would seem an unusual doctrine, and one not supported by the cited case, to say that JUSTICE STEVENS, with whom JUSTICE BRENNAN, JUSTICE MARSHALL, and JUSTICE BLACKMUN join, concurring in the judgment. Appellee Dayton Christian Schools, Inc. (School), employed Mrs. Linda Hoskinson as a teacher. Shortly after [*630] learning that she was pregnant, the School refused to renew Mrs. Hoskinson's teaching contract for the next academic year. The two reasons for this decision, according to the School, were (1) the School's belief that Mrs. Hoskinson should remain at home to supervise and care for her forthcoming child; and (2) the School's belief that Mrs. Hoskinson had violated the "Biblical chain of command" by consulting an attorney regarding her disagreement with the School's conviction that she remain at home. App. 115 (complaint of Dayton Christian Schools, Inc., et al.). Page 11 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 After her termination, Mrs. Hoskinson filed a sex discrimination charge against the School with appellant Ohio Civil Rights Commission. The Commission investigated her charge and, upon finding probable cause to believe that the School had violated § 4112.02 of the Ohio [***524] Revised Code, 1 scheduled a hearing. The School thereupon filed this action in Federal District Court seeking declaratory and injunctive relief. 1 That part: section provides, in "§ 4112.02 Unlawful discriminatory practices. "It shall be an unlawful discriminatory practice: "(A) For any employer, because of the race, color, religion, sex, national origin, handicap, age, or ancestry of any person, to discharge without just cause, to refuse to hire, or otherwise to discriminate against that person with respect to hire, tenure, terms, conditions, or privileges of employment, or any matter directly or indirectly related to employment." Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 4112.02 (Supp. 1985). In the District Court, the School argued that the Ohio antidiscrimination statute violates the First Amendment Religion Clauses as applied to sectarian schools. 2 The District Court determined that "[the] only conduct on the part of the Commission that is presently being threatened with sufficient [*631] immediacy and reality to present a justiciable controversy is the investigation, which has already taken place, and the pending hearing on the complaint filed by the [Commission] concerning the discharge of Mrs. Hoskinson." 578 F.Supp. 1004, 1029 [**2725] (SD Ohio 1984). Accord, id., at 1039. On the merits, the District Court concluded that the Commission's investigation and adjudication of sex discrimination charges was constitutional. The court recognized that "the statute could be ap- plied in any number of ways that could impermissibly interfere with" appellees' religious freedom, but it concluded that these concerns -- which relate to the possible remedies that might or might not be ordered if a violation is found -- were "hypothetical or speculative" and therefore not ripe on the current state of the record. Id., at 1028. 3 2 The School also argued that § 4112.02 of the Ohio Revised Code is unconstitutional on its face. The District Court held the section to be neither overbroad nor void for vagueness. Because the Court of Appeals invalidated the section as applied to the School, it did not address appellees' facial attack. The School no longer presses the argument that the statute is unconstitutional on its face. 3 "In permitting the [Commission] to exercise jurisdiction over the instant controversy, the Court has in no way determined either that the full force of [the Commission's] jurisdiction under [Ohio Revised Code] Chapter 4112 can be brought to bear on [Dayton Christian Schools] without impermissibly burdening [appellees'] first amendment rights or, even with respect to the present controversy, that any remedy deemed appropriate by the [Commission] should they find [Dayton Christian Schools] liable, would necessarily present no further first amendment problems. However, because many of the concerns voiced by [appellees] about state encroachment on their religious freedoms remain as yet only possibilities, they cannot serve as the basis for the issuing of a permanent injunction against the [Commission]." 578 F.Supp., at 1041. The Court of Appeals reversed. 766 F.2d 932 (CA6 1985). It recognized that the School "[challenged] only the [Commission's] exercise of jurisdiction and its issuance of the complaint Page 12 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 in this case." Id., at 950, n. 31. It further acknowledged that "an order of reinstatement or backpay is not at issue in this case." Ibid. It nevertheless determined that the "chilling knowledge" that the School's selection criteria for teachers "will be reevaluated, and, perhaps, adjusted by the state applying secular criteria" placed an impermissible burden on appellees' religious freedoms. Ibid. Looking into the future, the Court of Appeals also concluded that the [*632] "highly intrusive nature" of backpay and reinstatement, as well as the "continuing surveillance implicated by the conciliation agreement proposed by the Commission" [***525] and rejected by the School, "reveal the 'significant risk that the First Amendment will be infringed.'" Id., at 942-943 (quoting NLRB v. Catholic Bishop of Chicago, 440 U.S. 490, 502 (1979)). Accord, 766 F.2d, at 951. Like the majority, I agree with the District Court that neither the investigation of certain charges nor the conduct of a hearing on those charges is prohibited by the First Amendment: "the Commission violates no constitutional rights by merely investigating the circumstances of Hoskinson's discharge in this case, if only to ascertain whether the ascribed religiousbased reason was in fact the reason for the discharge." Ante, at 628. I further agree with the District Court that any challenge to a possibly intrusive remedy is premature at this juncture. As the majority points out, ante, at 629, the Commission recognizes religious justifications for conduct that might otherwise be illegal. Thus, although § 4112.02 forbids discrimination on the basis of religion, the Commission has dismissed complaints alleging religious discrimination by religious educational institutions, see Menz v. St. Pius School, No. 3823 (1983), and in particular has dismissed complaints by teachers against sectarian schools for limiting employment to instructors who subscribe to the appropriate faith, see In re St. Michael's School, No. 2726 (1976); In re St. Mary of the Falls, No. 948 (1975). It bears emphasis that the Commission dismissed these complaints only after investigating charges of discrimination, finding probable cause that the statute had been violated, and holding a hearing on the complaint. It therefore follows that the Commission's finding of probable cause and decision to schedule a hearing in this case does not also mean that the Commission intends to impose any sanction, let alone a sanction in derogation of the First Amendment's Religion Clauses. In view of this fact, the District [*633] Court was entirely correct [**2726] in concluding that appellees' constitutional challenge to the remedial provisions of the Ohio statute is not ripe for review. 4 Accordingly, I concur in the judgment. 5 4 I fully agree with the majority's general statement that "a reasonable threat of prosecution for conduct allegedly protected by the Constitution gives rise to a sufficiently ripe controversy." Ante, at 626, n. 1 (citation omitted). Thus, when the constitutional challenge is to the arrest and initiation of criminal proceedings -- as was the case with the pamphleteer in Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452, 458460 (1974), and the operators of the bars in Doran v. Salem Inn, Inc., 422 U.S. 922, 930-931 (1975) -- a "reasonable threat" of arrest and prosecution is sufficient to make the controversy ripe for judicial review. For purposes of this case, it follows from Steffel and Doran that appellees' First Amendment challenge to the Commission's decision to investigate and adjudicate a charge of sex discrimination against the School is ripe, because the investigation has been completed and the matter set for hearing. However, it does not follow that a challenge to whatever remedy might ultimately be fashioned Page 13 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 (should liability be established and relief ordered) is ripe merely upon a showing of a "reasonable threat" that proceedings will commence. Doran and Steffel do not suggest this result, for they did not address the constitutionality of possible remedies for the conduct prosecuted in those cases. In view of the absence of any finding of liability in this case, and the Commission's demonstrated willingness to tailor remedies to accommodate the exercise of religious freedoms, there is plainly no "reasonable threat" that an overly intrusive remedy will trench on appellees' First Amendment rights. To hold otherwise would require the District Court to detail the constitutionally permissible range of the Commission's sentencing discretion in advance of any facts regarding the School's discriminatory conduct or any explanation by the Commission justifying the relief it might fashion. Either or both of these items of information would inform the First Amendment analysis and might prove decisive in determining the constitutionality of the Commission's hypothesized remedy. 5 I do not agree with the majority that the doctrine of abstention associated with Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971), required the District Court to dismiss appellees' complaint. That disposition would presumably deny the School a federal forum to adjudicate the constitutionality of a provisional administrative remedy, such as reinstatement pending resolution of the complainant's charges, even though the constitutional issues have become ripe for review by the Commission's entry of a coercive order and the Commission refuses to address the merits of the constitutional claims. Younger abstention has never been applied to subject a federalcourt plaintiff to an allegedly unconstitutional state administrative order when the constitutional challenge to that order can be asserted, if at all, only in state-court judicial review of the administrative proceeding. See Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S., at 462 (holding that Younger abstention is inappropriate when no state-court proceeding "is pending at the time the federal complaint is filed," because in that circumstance "federal intervention does not result in duplicative legal proceedings or disruption of the state criminal justice system"; it cannot "be interpreted as reflecting negatively upon [a] state court's ability to enforce constitutional principles"; and the absence of a pending state-court proceeding deprives "the federal plaintiff [of] a concrete opportunity to vindicate his constitutional rights"). See also Middlesex County Ethics Committee v. Garden State Bar Assn., 457 U.S. 423, 437 (1982) (requiring abstention where "an adequate state forum for all relevant issues has clearly been demonstrated to be available prior to any proceedings on the merits in federal court" (citation omitted)). REFERENCES 32A Am Jur 2d, Federal Practice and Procedure 587, 1797, 1803 1 Federal Procedure, L Ed, Access to District Courts 1:577, 1:583; 2 Federal Procedure, L Ed, Appeal, Certiorari and Review 3:10 2 Federal Procedural Forms, L Ed, Appeal, Certiorari and Review 3:764; 8 Federal Procedural Forms, L Ed, Declaratory Judgments 21:34 11 Am Jur Pl & Pr Forms (Rev), Federal Practice and Procedure 1991-1995 USCS, Constitution, 1st Amendment; 28 USCS 1254 Page 14 477 U.S. 619, *; 106 S. Ct. 2718, **; 91 L. Ed. 2d 512, ***; 1986 U.S. LEXIS 71 US L Ed Digest, 683, 691, 700.5 Appeal 254; Courts Index to Annotations, Abstention Doctrine; Appeal and Error; Courts; Pending Actions and Proceedings; Sex Discrimination; Supreme Court of United States Supreme Court's rule, and exceptions to rule, against federal judicial intervention in pending or threatened state criminal proceedings. 44 L Ed 2d 692. Annotation References: Exhaustion of state administrative remedies as prerequisite to federal civil rights action based on 42 USCS 1983. 43 L Ed 2d 833. Supreme Court's views as to application to noncriminal proceedings of rule against federal judicial intervention in pending or threatened state proceedings. 73 L Ed 2d 1416. Construction and application of 28 USCS 1254(2) authorizing appeal to Supreme Court from Court of Appeals judgment invalidating state statute. 27 L Ed 2d 840. 100297 ********** Print Completed ********** Time of Request: Friday, April 02, 2010 Print Number: 2841:213628183 Number of Lines: 541 Number of Pages: Send To: SCHUBMEHL, MEGHAN COLUMBIA LAW SCHOOL 435 W 116TH ST NEW YORK, NY 10027-7201 12:51:31 EST