Indigo

advertisement

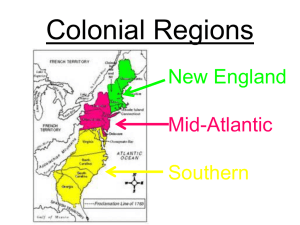

CRINKLES Jan./Feb. 2004, pp. 24+ Copyright © 2004, CRINKLES. Published by LMS Associates LLC. January/February 2004, pp. Indigo The Blue Gold of the South By Robin Pickens • Do you have a favorite pair of blue jeans? Did you ever wonder about the origin of the blue color? Today, your blue jeans are dyed with synthetic (human-made) chemicals. However, until about 100 years ago, the only way to dye clothes blue was to use natural dyes, many of which came from plants. The King of Dyes For millennia, the most favored natural dye was from the indigo plant. Its properties have been known for thousands of years. It was used in Egypt as early as 1600 BC. Egyptian mummies were wrapped in fabric dyed with indigo. Indigo has been linked with myth, superstitious ritual, and wealth. By the 17th century, indigo was in great demand throughout the world. Indigo was the best natural dye because it produced a rich, blue color that did not fade like other natural dyes. Indigo could be used to dye almost any natural fiber, from animal fibers to plant fibers. It was considered the "king of dyestuffs." Indigo gained in demand as common trade. It only grew in warm climates, such as India, Asia, South America, and Central America. These countries shipped it to other countries that were not able to grow indigo. Europe was one country where indigo was in high demand. English winters were too cold for the plant to grow. Those who could grow and sell indigo became rich. In 1663, King Charles II of England was in need of money. To settle a debt, he granted colonial land to eight friends. These "Lords of Proprietors" settled the land that the King named "Carolina" or what is today called North Carolina and South Carolina. Their settlement, the first in Carolina, was called Charles Town. It was later shortened to Charleston. Indigo and Charleston, South Carolina Charlestown was located by the rivers and the Atlantic Ocean, which was favorable for the new colony's economy. England was eager for the natural resources that Charlestown offered. Because Charlestown was a port city, it provided a market for trade of indigo, rice, naval stores (products made from pine trees, such as turpentine, pitch, and lumber for building and repairing ships), animal skins, and Native American goods. It would soon become the richest colony in the Americas. By the 1740s, indigo was a promising crop. Charlestown's high ground had sandy, loose soil, which was perfect for growing indigo. Colonists had unsuccessfully tried to grow other crops such as corn and potatoes. The crops did not thrive, because the ground was swampy. At this time, indigo was so valuable that the king of England offered a bounty to planters who successfully yielded indigo crops. This period was known as the "indigo Bonanza". First Lady of Blues By the mid 1750s, indigo was a booming industry. South Carolina exported nearly one million pounds of the blue dye per year! This bonanza in South Carolina was in large part due to a young woman, Miss Eliza Pinckney. She defied the conventions of her time and was an astute businesswoman. She ran three of her father's plantations when she was just sixteen years old! Her family's plantation needed a cash crop. Eliza chose indigo. Not fearful of the risks, Eliza experimented with indigo seeds her father sent from the West Indies. In 1744 she finally had a successful crop. She did not keep all the indigo seeds to herself. She gave them away to friends and neighbors. The challenges did not end there. Eliza had no one to explain to her the proper way to process the plants into the valuable dye. Not daunted, Eliza figured out the processing by trial and error. This was critical, because the processing determined the quality of the dye. She also shared her hard-earned knowledge about the processing of indigo. Soon, millions of pounds of indigo cakes were being exported to other countries. Plantation Life Indigo created fortunes and helped to form the southern plantation society. Some plantation owners became as wealthy as European royalty. Plantations were southern farms that were usually dedicated to the production and sale of a single crop. Plantations relied on the labor of many slaves, and were run to make money. Plantation owners differed from other southern farmers who may have even owned a few slaves because they participated in a market economy. This was risky business. If the crop failed, or no one bought their crop yield, they would lose money and their survival was threatened. Indigo production required intense manual effort. In the South, this manual labor was slave labor. Many slaves that manufactured the indigo dye became sick and died, probably from cancer. Demand for field labor increased the English slave trade from Africa. This is another reason indigo production was successful in the South. It fit into the already existing plantation and slave labor culture. By 1730, two-thirds of the South Carolina population were African slaves. Plantation owners believed that the plantation culture could not survive without slave labor. Revolution and Indigo Indigo production continued up until the Revolutionary War. Until that time, indigo was more valuable than gold. It was considered the "blue gold" of the south. Without indigo, many cities such as Georgetown would not have existed nor prospered were it not for the plant and the dye it produced. Indigo trade provided the wealth that made it possible for the colonies to sever ties with England. Ironically, after the Revolutionary War, the colonies could no longer depend upon indigo trade to England. England was no longer ruling over the colonies, and thus the state lost its indigo bounty and principal trading partner. So the south changed its economy. Rice, cotton, and tobacco took indigo's place as cash crops. Nevertheless, even today, indigo has retained a value and popularity that has not really diminished. Indigo Magic Just looking at the indigo plant, you would never know that it could yield such a deep, beautiful blue color. The plant itself is not remarkable at all. It has small green leaves, pinkish pea-shaped flowers in late summer, and small bean-like seed pod clusters in fall. Colonists had to go through a long and complicated process to get the blue indigo dye: First, harvested indigo plants were placed in three successive fermentation vats or pits filled with water. As the plants sat in the vats, they rotted, or fermented. This produced a liquid, called indican. Indican was formed from a chemical reaction between the plant debris, the water, and the air. The fermented plants were stirred with large paddles. Then, the water was drained. The remaining residue was strained, and left to dry. This resulted in a stiff, blue paste. The paste was formed and cut into blocks called cakes. The indigo cakes could then be shipped. To dye fabric, the cakes were dissolved in water with lime, potash, or soda. This would sit for several days. The solution turned a copper color. The solution was now ready to dye fabrics. The fabric was submerged into the dye solution for a few minutes. When it was lifted out, an amazing thing happened. Like magic, the fabric turned a deep blue indigo color. Read More About It: Resources on Indigo and South Carolina: These books are mainly for research. Balfour-Paul, Jenny. Indigo. British Museum Press, 1998. 264 p. This popular blue dye has been around for more than 5,000 years. Read the story of the world's oldest and most valued dye. Messmer, Catherine C. South Carolina Low Country: A Past Preserved. Photography by C. Andrew Halcomb. Sandlapper Publishing Co., 1988. 143 p. Contains pictures and history of plantations and churches from the South Carolina cities of Charleston, Georgetown, and Beaufort counties. Pettit, Florence. America's Indigo Blues: Resist--Printed and Dyed Textiles of the Eighteenth Century. Hastings House, 1988. 469 p. Detailed reference about indigo in America's colonial period. Weir, Robert M. Colonial South Carolina: A History. University of South Carolina Press, 1997. 430 p. A great source on one of the most interesting colonies in North America. These books will be interesting to read. Krebs, Laurie. A Day in the Life of a Colonial Indigo Planter. PowerKids Press, 2003. 24 p. Read the story of a typical day for Eliza Pinckney, a remarkable woman in Colonial South Carolina. L'Hommedieu, Arthur John. From Plant to Blue Jeans. Children's Press, 1998. 32 p. Discover the process of making blue jeans, from the harvesting of cotton to sewing the finished product. Whitehurst, Susan. The Colony of South Carolina. Rosen Publishing Group PowerKids Press, 2000. 24 p. From the founding of Carolina to just after the Revolutionary War, read about the colony of South Carolina. On the Web: Eliza Lucas Pinckney http://scetv.org/legacy/laureates/Eliza%20Lucs%20Pinckney.html From the South Carolina public television web site, a brief biography of Eliza Pinckney. Includes a short video segment. Part of the SCETV "Legacy of Leadership" series. South Carolina Colonization http://www.usgennet.org/usa/topic/colonial/book/chap4_4.html If you would like to find out more about the colonization of South Carolina, look at this web site. South Carolina Women of the American Revolution http://sciway3.net/clark/revolutionarywar/elizelucas.html Read about the background of Eliza Pinckney. Trade Topics http://www.apl.com/boomerangbox/d110501.htm A short history of indigo. True Colors http://www.si.edu/lemelson/centerpieces/whole_cloth/u3tc/u3materials/tcessa y.html "Where Do Colors Come From?" Find out about the chemistry and history of dyeing at this web site. Who Was Eliza Pinckney? Eliza Pinckney was inducted into the South Carolina business hall of fame in 1989, the first woman to be so honored. She spent her last days with her daughter at the Hampton Plantation which is now a state park. You can see the tree under which George Washington stood while visiting her. Learn more about her at: http://www.distinguishedwomen.com/biographies/pinckney.html http://www.alexanderstreet2.com/NWLDLive/bios/A21BIO.html Color by Numbers Can you find the indigo leaves? Follow the codes and color the spaces according to the numbers. (See picture, "Indigo Coloring Activity" and "Indigo Coloring Activity [Answer].") H