Chapter 14

advertisement

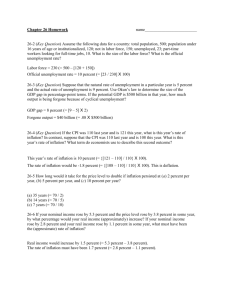

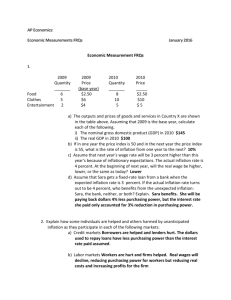

471 C h a p t e r 14 INFLATION O u t l i n e From Rome to Rio de Janeiro A. Inflation is a very old problem and some countries even in recent times have experienced rates as high as 40% per month. B. The United States has low inflation now, but during the 1970s the price level doubled. C. Why does inflation occur, how do our expectations of inflation influence the economy, is there a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment, and how does inflation affect the interest rate? I. Inflation and the Price Level A. Inflation is a process in which the price level is rising and money is losing value. 1. Inflation is a rise in the price level, not in the price of a particular commodity. 2. Figure 29.1 (page 678/332) illustrates the distinction between inflation and a one-time rise in the price level. 3. The inflation rate is the percentage change in the price level; that is, the inflation rate is [(P1 – P0)/P0] 100 where P1 is the current price level and P0 is last year’s price level. 4. Inflation can result from either an increase in aggregate demand--demand-pull—or a decrease in aggregate supply—cost-push. II. Demand-Pull Inflation A. Demand-pull inflation is an inflation that results from an initial increase in aggregate demand. 1. Demand-pull inflation may result from any factor that increases aggregate demand. 2. Two factors controlled by the government are increases in the quantity of money and increases in government purchases. 3. A third possibility is an increase in exports. A. Initial Effect of an Increase in Aggregate Demand 1. Figure 29.2 (page 679/333) illustrates the start of a demand-pull inflation 2. Starting from full employment, an increase in aggregate demand shifts the AD curve rightward. 3. Real GDP increases, the price level rises, and an inflationary gap arises. 4. The rising price level is the first step in the demand-pull inflation. B. Money Wage Rate Response 1. The higher level of output means that real GDP exceeds potential GDP—an inflationary gap. 2. The money wages rises and the SAS curve shifts leftward. 3. Real GDP decreases back to potential GDP but the price level rises again. C. A Demand-Pull Inflation Process 1. Figure 29.3 (page 680/334) illustrates a demand-pull inflation spiral. 2. Aggregate demand keeps increases and the process just described repeats indefinitely. 3. Although any of several factors can increase aggregate demand to start a demand-pull inflation, only an ongoing increase in the quantity of money can sustain it. 4. Demand-pull inflation occurred in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s. III. Cost-Push Inflation A. Cost-push inflation is an inflation that results from an initial increase in costs. There are two main sources of increased costs: an increase in the money wage rate or an increase in the money price of raw materials, such as oil. A. Initial Effect of a Decrease in Aggregate Supply 1. Figure 29.4 (page 682/336) illustrates the start of cost-push inflation. 2. A rise in the price of oil decreases short-run aggregate supply and shifts the SAS curve leftward. 3. Real GDP decreases and the price level rises—a combination called stagflation. 4. The rising price level is the start of the cost-push inflation. B. Aggregate Demand Response 1. The initial increase in costs creates a one-time rise in the price level, not inflation. To create inflation, aggregate demand must increase. 2. Figure 29.5 (page 682/336) illustrates an aggregate demand response to stagflation, which might arise because the Fed stimulates demand to counter the higher unemployment rate and lower level of real GDP. 3. The increase in aggregate demand shifts the AD curve rightward. 4. Real GDP increases and the price level rises again. C. A Cost-Push Inflation Process 1. Figure 29.6 (page 683/337) illustrates a cost-push inflation spiral. 2. If the oil producers again raise the price of oil to try to keep its relative price higher, and the Fed responds with a further increase in aggregate demand, the process of cost-push inflation continues. 3. Cost-push inflation occurred in the United States during 1974–1978. IV. Effects of Inflation A. Unanticipated Inflation in the Labor Market 1. Unanticipated inflation has two main consequences in the labor market: it redistributes income and brings departures from full employment. 2. Higher than anticipated inflation lowers the real wage rate and employers gain at the expense of workers. 3. Lower than anticipated inflation raises the real wage rate and workers gain at the expense of employers. 4. Higher than anticipated inflation lowers the real wage rate, increases the quantity of labor demanded, makes jobs easier to find, and lowers the unemployment rate. 5. Lower than anticipated inflation raises the real wage rate, decreases the quantity of labor demanded, and increases the unemployment rate. 6. Unanticipated inflation imposes costs on both workers and firms. B. Unanticipated Inflation in the Market for Financial Capital 1. Unanticipated inflation has two main consequences in the market for financial capital: it redistributes income and results in too much or too little lending and borrowing. 2. If the inflation rate is unexpectedly high, borrowers gain but lenders lose. 3. If the inflation rate is unexpectedly low, lenders gain but borrowers lose. 4. When the inflation rate is higher than anticipated, the real interest rate is lower than anticipated, and borrowers want to have borrowed more and lenders want to have loaned less. 5. When the inflation rate is lower than anticipated, the real interest rate is higher than anticipated, and borrowers want to have borrowed less and lenders want to have loaned more. C. Forecasting Inflation 1. To minimize the costs of incorrectly anticipating inflation, people form rational expectations about the inflation rate. 2. A rational expectation is one based on all relevant information and is the most accurate forecast possible, although that does not mean it is always right; to the contrary, it will often be wrong. D. Anticipated Inflation 1. Figure 29.7 (page 686/340) illustrates an anticipated inflation. 2. Aggregate demand increases, but the increase is anticipated, so its effect on the price level is anticipated. 3. The money wage rate rises in line with the anticipated rise in the price level. 4. The AD curve shifts rightward and the SAS curve shifts leftward so that the price level rises as anticipated and real GDP remains at potential GDP. E. Unanticipated Inflation 1. If aggregate demand increases by more than expected, inflation is higher than expected. Money wages do not adjust for all the inflation, and the SAS curve does not shift leftward enough to keep the economy at full employment. Real GDP exceeds potential GDP. Wages eventually rise, which leads to a decrease in the SAS. The economy experiences more inflation as it returns to full employment. This inflation is like a demandpull inflation. 2. If aggregate demand increases by less than expected, inflation is less than expected. Money wages rise too much and the SAS curve shifts leftward more than the AD curve shifts rightward. Real GDP is less than potential GDP. This inflation is like a cost-push inflation. F. The Costs of Anticipated Inflation 1. Anticipated inflation occurs at full employment with real GDP equal to potential GDP. 2. But anticipated inflation, particularly high anticipated inflation, inflicts three costs: a) Transactions costs. People spend money more rapidly when they anticipate high inflation and so transact more frequently. b) Tax consequences. Anticipated inflation reduces the after-tax return from saving, which decreases capital accumulation and long-term economic growth. c) Increased uncertainty. A high inflation rate increases uncertainty, which makes long-term planning for investment more difficult and causes people to spend time forecasting inflation rather than undertaking more productive activities. Both of these effects reduce the economy’s long-term growth rate. V. Inflation and Unemployment: The Phillips Curve A. A Phillips curve is a curve that shows the relationship between the inflation rate and the unemployment rate. There are two time frames for Phillips curves. B. The Short-Run Phillips Curve 1. The short-run Phillips curve shows the tradeoff between the inflation rate and unemployment rate holding constant the expected inflation rate and natural rate of unemployment. 2. Figure 29.8 (page 688/342) illustrates a short-run Phillips curve (SRPC)—a downward-sloping curve. 3. Figure 29.9 (page 689/343) shows that the negative relationship between the inflation rate and unemployment rate is explained by the AS-AD model. An unexpectedly large increase in aggregate demand raises the inflation rate and increases real GDP, which lowers the unemployment rate. So a higher inflation is associated with a lower unemployment, as shown by a movement along a short-run Phillips curve. C. The Long-Run Phillips Curve 1. The long-run Phillips curve shows the relationship between inflation and unemployment when the actual inflation rate equals the expected inflation rate. 2. Figure 29.10 (page 690/344) illustrates the long-run Phillips curve (LRPC) which is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment. 3. Along the long-run Phillips curve, because a change in the inflation rate is anticipated, has no effect on the unemployment rate. 4. Figure 29.10 (page 690/344) also shows how the shortrun Phillips curve shifts when the expected inflation rate changes. A higher expected inflation rate shifts the short-run Phillips curve upward by an amount equal to the increase in the expected inflation rate. D. Changes in the Natural Rate of Unemployment 1. A change in the natural rate of unemployment shifts both the long-run and short-run Phillips curves. 2. Figure 29.11 (page 691/345) illustrates. E. The U.S. Phillips Curve 1. The data for the United States are consistent with a shifting short-run Phillips curve. It has shifted because of changes in the expected inflation rate and changes in the natural rate of unemployment. 2. Figure 29.12 (page 691/345) shows the actual path traced out in inflation rate-unemployment rate space [panel (a)] and interprets this as four separate short-run Phillips curves [panel (b)]. VI. Interest Rates and Inflation A. Interest rates and inflation rates are correlated, although they differ around the world. Figure 29.13 (page 346) plots U.S. data over time and international data, showing that other things the same, higher inflation correlates with higher nominal interest rates. B. How Interest Rates are Determined 1. The nominal interest rate and real interest rate differ. 2. The real interest rate is determined by investment demand and saving supply in the global capital market. a) The real interest rate adjusts to make the quantity of investment equal the quantity of saving. b) National rates vary because of differences in risk. 3. The nominal interest rate is determined by the demand for money and the supply of money in each nation’s money market. The nominal interest rate adjusts to make the quantity of money demanded equal to the quantity supplied. C. Why Inflation Influences the Nominal Interest Rate The key relationship is that the nominal interest rate equals the real interest rate plus the expected inflation rate.