Konkurso IPO Osle 2012 rezultatų protokolas

advertisement

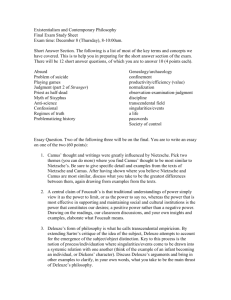

Konkurso IPO Osle 2012 rezultatų protokolas Konkursui darbus atsiuntė 4 mokiniai: Tadas Kriščiūnas Vilniaus licėjus 4c Austėja Masliukaitė Vilniaus licėjus 4a Miša Skalskis Vilniaus licėjus, 3b klasė Dominykas Milašius Kauno jėzuitų gimnazija 4a Darbai buvo vertinami pagal keturis kriterijus 1.Problemos supratimas 0-10 2. Kompetencija 0-10 3. Loginis nuoseklumas 0-10 4. Originalumas 0-10 Pagal šiuos kriterijus darbai įvertinti: 1. Miša Skalskis 1.-10; 2.-10; 3.- 10; 4-10. Viso 40 2. Tadas Kriščiūnas 1.-10; 2.-10; 3.- 10; 4-10. Viso 40 3. Dominykas Milašius 1.-10; 2.-9; 3-10; 4-10. Viso 39 4. Austėja Masliukaitė 1.-10; 2.-8; 3.-8; 4.-10. Viso 36 Visi pretendentai parašė darbus, kurie liudija jų pasirengimą tarptautinei olimpiadai. Pagal konkurso rezultatus pirmenybę vyksti į IPO 2012 Osle įgija Miša Skalskis bei Tadas Kriščiūnas. Jiems atsisakius – Dominykas Milašius;. Jam atsisakius – Austėja Masliukaitė. Labai prašome kuo greičiau atsiųsti savo sutikimą vykti į olimpiadą IPO Siuskite tikslius asmeninius duomenis: pilna vardą, pavardę, asmens tapatybės kortelės nr., asmens kodą, adresą, E-mailą, gimimo datą, telefoną, tėvų sutikimo patikinimą. Siųskite jurabara@gmail.com Prisegame atsiųstus darbus: Autorius: Miša Skalskis, Mokytojas: Ernestas Šidlauskas, Vilnius, 2012 “Philosophers are always recasting and even changing their concepts: sometimes the development of a point of detail that produces a new condensation, that adds or withdraws components, is enough” Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari 1 It’s not a secret that philosophy exists without any hopeful signs of progress. It always creates, rethinks, criticizes the biggest ideological projects of hers; and yet no philosopher has said his final word in this polemics; it is even silly to believe that one day this might happen. What causes this lack of progress in the history of ideas? Why philosophers recast and change their ideas? And who is responsible for the changes in their concepts? At first, it should be considered what topics this essay is going to cover. We need to clarify the meaning of the given quotation and put it into some frame. First of all, how can the concepts change their meaning? Is it because the author or philosopher of the concept has changed his opinion, or is it because the concept itself cannot be articulated without any pervasion of meaning? The quotation directly points towards the link between the philosophers and their concepts, so as we see, there are three main problems, which should be analyzed more carefully: philosophers, the creators of concepts, concepts and the link, a connection between both, situated in language. How concepts can be introduced into inter-subjective plane? American semiotic Ch. S. Peirce in his writings stated that: ‘The only thought, then, which can possibly be cognized, is thought in signs. But thought which cannot be cognized does not exist. All thought, therefore, must necessarily be in signs’1. When we have an idea or a thought we definitely are going to share it with someone; and when we speak, we use our language made of different signs! Thus, when speaking about concepts, we should define the medium of their appearance, the language in which the concepts are created. And what is more important, we shouldn’t forget, that concepts are not only created, but also shared, and so should be recognized and identified by the other. Hence, we need to designate, how the meaning is created, how a certain words or concepts can bear their meaning? Concepts and language are strongly related and inseparable, so the first point of this essay is going to cover two out of three of above mentioned problems: concepts and language, together. Additionally, it’s worth analyzing, why do philosophers change their concepts? What drives the philosophers to alter these concepts, and why it is difficult to make them stable? Is it of conscious or unconscious concern? Second point discussed in this essay is going to be about those, who create concepts, driven by many different factors like desire (Freud, Lacan), production desire (Deleuze & Guattari), and change them, intentionally or unaware. And finally, if the fact, that it is impossible to keep the concepts away from delusion, is true, we will try to derive some short ethical implications in our conclusion. 1 Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, 8 vols. 1931–1958. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Volume 5, §251. 2 Rules of a chess game The first thing one might notice is that signs and their referent are separate, because, when ‘a=a’ and ‘a=b’, we see that the ‘a’ and ‘b’ means the same thing, but the way they represent their referent are different. Thus the link between signs and their referents is merely arbitrary. Different nations named thing independently of the extra-linguistic world, except in the cases of onomatopoeia; that explains way in different languages words differ. If the signs are created according to the imagination of the speaker, therefore it cannot posses meaning in it, thereby it is obvious, that we should search for the meaning in relation between those signs. First who introduced language as a self-contained system was Ferdinand de Saussure. He realized that the historical approach to language, when it is believed, that signs get their meaning from extra-linguistic reality, is not going to give any answers; it cannot explain how words can mean something. So a language, as understood by Ferdinand de Saussure, is a diacritic system in which elements do not posses positive meaning in them, but rather they receive meaning because of the interrelationship between this units or signs: ‘in language [langue] there are only differences. Even more important a difference generally implies positive terms between which the difference is set up; but in language, there are only differences without positive terms’2 That implies that language is a totality of differences, in which certain element obtain its meaning only because of the interrelationship with the other elements. Hence, as we already mentioned, in contrast with traditional linguists, he showed that there is no relationship between meaning and things; and, what is more, he pointed out that the relation between signifier (signifiant, written word or soundpattern) and the signified (signifieґ, meaning) is arbitrary; consequently the language is absolutely autonomous in relation to reality. Delusion of language and identity As we mentioned above, Saussure considered language as a structure. He called this structure – langue. A term langue means an inter-subjective system or structure made of oppositions between its elements or signifiers. From the first view everything seems fine; the language still may possess concrete meaning in its structure. But, if the signifier gets the meaning because of its difference with other signifier, shouldn’t the latter also receive its sense due to ongoing signification process and incorporate other signifiers? The positive answer to this question is given in the 2 Ferdinand de Saussure. 1993. Course in General Linguistics, trans Roy Harris, London: Duckworth, p. 118. 3 deconstruction theory of Jacques Derrida, where he suggests his own interpretation of language and identity. a. Famous French post-structuralist thinker agrees that meaning is uttered through the differences, but he adds that any signified is already a signifier of the other signified and this new signified is a signifier too, and so on and so forth. ‘There the signified always already functions as a signifier. The secondarity that it seemed possible to ascribe to writing alone affects all signifieds in general, affects them always already, the moment they enter the game.’3 As we see, there is no structure at all, every time signifiers make sequences of reference, which ways are anarchic. So, first of all, Derrida pointed out that meaning is possible due to differance, which means, that raison d’etre arouses due to uninterruptible signification process in time; every signified already is a signifier to other signifiers. Derrida obliterated the difference between signifier and signified. Thus, even writing or reading is already made of signifiers, which evokes uninterruptible games of language. From Derrida’s oeuvre we see that there is no structure, every meaning plays its own game. Every time when something is expressed the meaning cannot be the, because the ways of signification are unpredictable. This concept of delusion in meaning Derrida called dissemination. b. The concept of identity, as postulated by Plato, Aristotle, Leibniz, Bertrand Russell and others, played a magnificent role, throughout the history of Western philosophy. Derrida was brave enough and tried to countervail the logic of identity, which might be formulated like this: The law of identity: ‘Whatever is, is.’ The law of contradiction: ‘Nothing can both be and not be.’ The law of excluded middle: ‘Everything must either be or not be’ 4 Derrida showed that time is essential for meaning to emerge, and signifiers get their meaning, as in R. Jakobson’s binarism, because of the oppositions; signifier can be, because it is not itself and is other than itself. Différance, made from the French word différer, means both ‘to defer’ and ‘to differ’, as the signifiers already bears the reference to another signifier. Thereby, Identity, as the meaning in the context of language, disseminate in time, so everything can be and not be at the same time. So we can reformulate the logic of identity in such way: ‘Whatever is, may be not.’ 3 Jacques Derrida. 1997. Of Grammatology, trans G.Ch. Spivak, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 7 4 Russell Bertrand. 1973. The Problems of Philosophy, London and New York: Oxford University Press, p. 40 4‘Everything can both be and not be.’ ‘Everything cannot either be or not be’ As an example of such aporetic logic Derrida use word pharmakon, which is neither drug nor poison, and supplement, which he takes from Rousseaunian concept of nature. Rousseau saw a nature as a self-sufficient, which can be supplemented by education. But additionally he said that without education nature cannot express itself, so: ‘…the supplement supplements. It adds only to replace. It intervenes or insinuates itself in-the-place-of; if it fills, it is as if one fills a void.’5 The supplement not only adds something to the nature, but it substitutes the nature, it doesn’t make nature more positive, it shows that nature is lacking and not selfsufficient. This again means that identity always has lack of something, which masks its selfefficiency and shows that it needs supplements to fill this gap. Lack constitutes identity, so the latter cannot be self-efficient. There is nothing outside of the text6 or am I what I am? As seen from Peirce quotation at the beginning of this essay, every thought is mediated in signs. That means that as we think we use a systems of signs to express ourselves: ‘for Husserl, as we have seen, the voice - not empirical speech but the phenomenological structure of the voice - is the most immediate evidence of self-presence. In that silent interior monologue, where no alien material signifier need be introduced, pure self-communication (auto-affection) is possible.’7indicated Spivak. First, we see that only while speaking we can testify our self-presence, the Cartesian ego. And secondly Spivak noted that, for Husserl, self-communication does not need any signifiers; the pure though is built without any intervention of alien source. However Derrida, while deconstructing metaphysical identity, argued that any signified is already a signifier, so even an auto-affection cannot be a pure thought and it is supplemented by principle of signification. And what is more, he believed that principle of signification is prior to self-identical entity. Thinking is familiar to writing, in both signs are created; thinking is just a supplement, which substitutes selfefficient ego, but only in cogitating or while thinking ego can express itself. Thus even consciousness is mediated in language. When talking about ego as a sequence of signs, we must not forget the principle of dissemination, only possible due to différance. The unlimited semiosis, as Peirce would have called Jacques Derrida. 1997. Of Grammatology, trans G.Ch. Spivak, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 145 6 Ibid, p. 158 7Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. 1997. Translators Preface. Derrida. Of Grammatology, trans G.Ch. Spivak, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. liii 5 5 it, or when a sign only points towards another sign and so ad infinitum, indicates that we cannot control anarchic movements of the process of signification. It means that ego is not responsible for itself in the role of cogito. The expression of ‘I’ cannot be identical to the ego, because it would be a reference to an extra-linguistic reality, which is illegal. Therefore even reading is similar to writing; we recreate the incontrollable sequence of signification which every time is different due to the changes in context. Even the slightliest changes in context, will bring new connotations to the meaning; for example when a ‘yes’ is said in an everyday life or in a marriage ceremony. $ and desire of other Similarly to Derrida’s view, famous French psychoanalytic, Jacques Lacan postulated that subject is not self-sufficient. He introduced a concept of a mirror stage; it’s when an infant, before he is able to talk, realizes himself as an entity in other. What he sees in the mirror is not the exact ‘I’ he thinks he sees. Yet he identifies himself through this picture and he thinks he is the one in the mirror. As we see, Lacanian subject ($) is divided into two parts: the subject as the other (autrui; the Imaginary) and the unrepresented kernel of ego. Before the ego has a possibility to see itself, it creates the image of pseudo-self in the other. ‘Here arises the ambiguity of a misrecognizing that is essential to knowing myself. For, in this "rear view," all the subject can be sure of is the anticipated image—which he had caught of himself in his mirror—coming to meet him.’8 We see that it is impossible to distinguish the Imaginary (la réalité) from real (le réel). But the Imaginary is already represented with a lack, because the ego can’t be symbolized precisely; it leaves ‘I’ incomplete. The lack is hidden from a subject through the fantasy, which is groundwork for réalité to happen. In such state of affairs every desire is traumatic, because the subject seeks not a genuine goal, but a false one, which makes his ambitions inaccessible. The only place where desire might be fulfilled is dreams. The desire in Lacanian psychoanalysis is derived from the gaze of the Other (Autrui) and not from the subject itself. So: the object of desire is out of the subject’s control; this object is provided by a social grid, the jouissance as a law. The psychoanalysis of Lacan was strongly criticized by Deleuze and Guattari in their Anti-Oedipus. As they said: ‘We attack psychoanalysis on the following points, which relate to its practice as well as its theory: its cult of Oedipus, the way it reduces everything to the libido and domestic investments, even when these are transposed and generalized into structuralist or symbolic Jacques Lacan. Ecrits: the first complete edition in English; trans Bruce Fink, New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, p. 684 8 6 forms.’9 They criticized Lacan because he confined a subject in a family cell and transferred desire to social institutions. Also they sought to de-identify subject, by suggesting schizoanalysis, when subject tries to decode and deterritorize himself. Body without organs and a productive desire Deleuze and Guattari reconsidered Freudian/Lacanian and Marxist ideas and postulated new way of interpreting the nowadays era. They saw Capitalism as a schizophrenic system, which is interested in deterritorialization of it subjects (emergent as refusal of institutions like church, family, etc.) because it sees subject as individual interested in profit; so this subject, as individual, needs to refuse any social arrangement. But capitalism do both, de-structures and re-structures social grid, because first, it needs autonomous individual and secondly, it needs social groupings in order to function. That’s why Capitalism is ambivalent, it should help individual to escape from social constraints, but at the same time it creates other constraints; and still, it allows the individual to be private; he is the only owner of his body and labour. The social grid became multipartite, made of different individuals, it avoids definition and articulation. What is more, by establishing schizoanalysis Deleuze and Guattari said that: ‘The unconscious poses no problem of meaning, solely problems of use. The question posed by desire is not "What does it mean?" but rather "How does it work?"’10; and that ‘desire makes its entry with the general collapse of the question "What does it mean?"’11 They see a desire as pure desire, by refusing to answer any question of its origins; they only seek to know where it would lead. This desire is vertically put on the horizontal milieu of a subject; the subject is connected to this desire. The desire generates production, which is the reality of a subject: ‘hence everything is production: production of productions, of actions and of passions; productions of recording processes, of distributions and of co-ordinates that serve as points of reference; productions of consumptions, of sensual pleasures, of anxieties, and of pain.’12 Thus, the subject is divided into to parts, desire machine and body without organs. Desire machine is connected to particular desire, without any possibility to change it or to fulfill it; body without organs is something that stands horizontally in the milieu of the subject, it suggests new ways for desire to emerge by decoding the vertical desire machines. So, as the subject becomes body without organs, his productive desire may be detoured in any direction. The productive desire of Deleuze’s and Guattari’s schizoanalysis is similar to Gilles Deleuze. 1995. Negotiations. trans by Martin Joughin. New Work: Columbia university press, p.20 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. 2000. Anti-Oedipus Minnesota : University of Minnesota Press, p.109 11 Ibid., p.109 12 Ibid., p.4 9 10 7 Nietzsche’s will-to-power. Although the Nietzsche’s will-to-power has some negative connotations, because it might be caused by the ressentiment. The productive desire is more spontaneous, coming from the unidentified subject itself, who reached the mode of active schizophrenia (not a medical schizophrenia, which is similar due to the loss of ego or identity). Thereby Deleuze and Guattari with their schizoanalysis tried to decode their subjects into bodies without organs: nomads without any religion, territory, social arrangement. Additionally, by breaking oedipal triangle, they showed that in Capitalistic society it is impossible to speak about humanity as a whole, because everyone now is individual with his own desires. But, apart all the disagreements between the Lacanian psychoanalysis and Deleuzian and Guattarian schizoanalaysis, they both clearly indicate, that the desire cannot be identified either from position of ‘I’ or from position of other. Moving towards the conclusion: ‘The logical picture of facts is a thought‘13 How can concepts change their meaning? In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, true knowledge is outside the cave and only a man free from the chains can see the sun; this man, after depicting reality, as Wittgenstein would have said, now should share this knowledge. Thus, the knowledge becomes contained in a thought; the ‘picture of facts’ or reality becomes a though, which is possible only trough a system of signs or, in other words, language. Therefore, as demonstrated by Derrida in his deconstruction theory, even while reading or perceiving information, subject actually participates in creating what Derrida spoke of as le sens. ‘The best one can say about disscusion is that it takes things no further, since the participants never talk about the same thing,‘ 14 – pointed out Deleuze and Guattari. The dissemination of meaning, doesn’t allow to the participants to understand each other; maybe they will do think, that they get the point of the discussion, but it won’t be the exact the same meaning to each of them. Plato thought that all knowledge comes from anamnesis. He believed that there is somewhere knowledge in pure state, but the possibility of genuine anamnesis is doubted due to theory of deconstruction. Even If anamnesis is possible, argues Derrida, it can’t be similar to each individual; it can’t be the same even to the same subject every time. In psychoanalysis of Lacan the reality or le reel is inaccessible due to distortion of language, which cannot represent the Real as it is, subject as the object a, similarly to Kantian Dingan-sich, is left unknowable. Judging about the subject participating in the creating of concepts, from the perspective of Lacanian psychoanalysis, it should be noted that the subject is cleaved ($). He is mediated in Ludwig Wittgenstein. Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari. What is philosophy?, trans H. Tomlinson and G. Burchell, New York : Columbia university press, p.28 13 14 8 language, which means that he cannot identify himself as it is; thus, the subject and his desires are created through the gaze of Simbolic or the Other (Autrui). So even the concepts, which he expresses cannot be genuine, because the language or Autrui finishes creating and forming the meaning of the concept. Consequently the concepts are created and changed not by the subject itself, but rather by the other. From the Deleuze’s and Guattari’s point of view the situation is quite different. When subject reaches its state of body without organs, when the oedipal triangle or the family cell and any social restraints are overcame, it is difficult to identify a him; therefore it’s difficult for such people to share and to communicate their concepts. Also, these concepts continuously change because of the lack of form in the subject, every time subject re-identifies himself, he do it differently. There is no vertical progress (Hegel), but rather horizontal, rhizomatic (Deleuze and Guattari) antiprogress as a movement towards perfection, because every concept or identity of such body without organs is absolute and perfect in their own way. ‘The concept is therefore both absolute and relative: it is relative to its own components, to other concepts, to the plane on which it is defined, and to the problems it is supposed to resolve; but it is absolute through the condensation it carries out, the site it occupies on the plane, and the conditions it assigns to the problem.’ 15 Conclusion ( finally! :) ) Milan Kundera, in his masterpiece “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”, used Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return. It suggests us the idea of cyclic history, when everything reoccurs, again and again, which roughly depicts the history of Western philosophy. This idea makes everything similarly unimportant, but at the other hand it gives the possibility to create over and over, from the start point. We may see a link between this allegory and the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari. Repetition was essential for them in forming their concept of meaning and schizoid being of a person, constituted from body without organs and production desire. Only through the repetitions we may distinguish differences (due to difference between actual and virtual), which becomes very important, because everything what occurs is original and absolute, yet relative. The cyclic modus of time doesn’t allow things to be the same every time they emerge, and the concepts are not an exception. Time makes the concepts, identity and the history of ideas itself unstable, but, as they are absolute every time they are articulated, we should not forget to create them, to fill every milieu of this world; to grasp and depict the moments of reality by achieving the state of the body without organs and connecting it to productive desire. Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari. What is philosophy?, trans H. Tomlinson and G. Burchell, New York : Columbia university press, p.21 15 9 “Philosophers are always recasting and even changing their concepts: sometimes the development of a point of detail that produces a new condensation1, that adds or withdraws components, is enough.” Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, “What is Philosophy?” 1 In the handout given to the participants of the olympiad a word “consideration” appeared instead of “condensation”. However, “condensation” and not “consideration” figures in the original Deleuze's text. author: Tadas Kriščiūnas, teacher: Ernestas Šidlauskas, Vilnius, 2012 In his “The Republic,” Plato argued that philosophers should seize the control of the state. According to him, philosophers were wiser than other men and the nearest to eternal Forms of various things, amongst which was, for example, Justice itself, therefore, they were most suitable for the role of rulers. This example from the history of philosophy indicates the importance of the definition of philosophy. If Plato's definition was right and philosophers were truly wisest, their seizure of power would be justifiable. However, if philosophers did not substantially differ from other people, a state ruled by “philosopher kings” could be a terrible place to live in. Everything depends on whether Plato got it right. In this essay, we will discuss the nature of philosophy using some ideas of a famous 20th century philosopher Gilles Deleuze. Talking more concretely, we will try to decipher the meaning of a quote taken from philosopher's collaborative work with Felix Guattari, “What is Philosophy?”, which has been specified as the title of the work. We are going to begin with some general observations about the nature of any definition of philosophy, then move on to a historical survey of various conceptions of philosophy and finally expose the conception of Gilles Deleuze by comparing it with that of Isaiah Berlin. We should note before commencing that, although the work we are going to discuss, “What is Philosophy?”, is written jointly by two people, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, we will use a single name – Gilles Deleuze – to refer to the author of the work. This is purely for the sake of brevity, without any hidden motives to neglect the other of the authors. I. The contours of a definition of philosophy If we are seeking a definition of philosophy, we should attempt to understand what a definition itself is at first. To accomplish this task, some remarks of W. V. Quine might be useful 2. Quine distinguishes between what we will call a dictionary definition and what he calls explication. On the one hand, a dictionary definition simply explains the meaning of a word as it is used in a language by giving an exact synonym of the word. On the other hand, explication refines or supplements the meaning of the word by giving a bulk of partial synonyms. Having distinguished between two different kinds of definitions, we are bound to ask which kind would a definition of philosophy belong to. In order to answer the question, let's observe at first that the word “philosophy” is, we might say, a technical one as it is not a part of ordinary, “natural” language but denotes a formal academic discipline (or the activities associated with the discipline). As the majority of such technical words, “philosophy” was intensionally designed (to name a then newly formed discipline). Being designed it is only one to name the discipline it is meant to name, because other words to name the same discipline would be redundant and hence irrational to design. Then the word “philosophy” has no exact synonym3. Therefore, any 2 Quine, W. V. O. Two Dogmas of Empiricism, in Huemer, Michael. Epistemology: Contemporary Readings. London: Routledge, 2002. pp. 176 – 194. 3 As a matter of fact, Quine (quite convincingly) argued that the idea of outright synonyms is flawed, hence there are no outright, exact synonyms at all. This fact gives additional support to our argument: a definition of philosophy should be of explicative kind. Putting it plainly, there is no firm meaning of the word “philosophy.” Consequently, a definition of philosophy is always normative (or even revisionary), emphasizing some aspects of the discipline but neglecting others, directing philosophers in their activities rather than simply describing what philosophers do. Having in mind the normative nature of any definition of philosophy, it seems more correct to talk in terms of competing and evolving conceptions of philosophy rather than one true way of doing philosophy. Therefore, the objective of the essay is to expose and explain Deleuzian conception of philosophy and contrast it with some other possible conceptions, but not to engage into discussions about the nature of philosophy. For there is no single true nature of philosophy, only different conceptions of it. II. A brief historical survey of the conceptions of philosophy Having clearly stated the nature of any definition of philosophy, there naturally comes an urge to take a quick historical survey of different conceptions of philosophy. Of course, there have been way too many of them to cover even a tenth here. However, it is possible to distinguish three major “eras” defined by dominating views on the nature of philosophy. We will call these “metaphysical”, “epistemological” and “conceptual” respectively. Perhaps the most convenient and concise way of representing each of the “eras” is to give an example of a famous philosopher belonging to it. The most vivid example of “metaphysical era” could be Aristotle. For Aristotle, “first philosophy” was metaphysics4. So, the main task of Aristotelian philosophy was to apprehend the basic structure of the world. All other tasks were thought to be dependent on the accomplishment of this most fundamental one. This might be related to Aristotelian conception of knowledge. For, in Aristotle's hierarchy of different types of knowledge, an intuitive apprehension of first principles, nous, is postulated. According to Aristotle, episteme, which is what we could equate to scientific knowledge, must be built upon first principles which can only be intuitively understood, so neither proved nor observed. We can clearly see that such a conception of knowledge allows metaphysics to take the place of “first philosophy,” for, if only we followed it, there would be no doubts about our availability to grasp the basic truths of the world. However, Descartes introduced an innovation here5. His famous method of systematic doubt forced him to reject Aristotelian notion of nous. Hence, for Descartes, the place of “first philosophy” is taken up by epistemology; question “What can we know about the world?” comes before the question “What kinds of things are there in the world?”. Descartes is a good example of a philosopher of “epistemological era.” But there also are philosophers who, as far as the question of “first philosophy” is concerned, do not agree with neither Aristotle nor Descartes. For example, W. V. Quine insisted on the unity of philosophy and science and wanted to replace epistemology with psychology without subscribing to Aristotelian nous or a similar notion6. Similarly, the philosopher this essay is going definition of philosophy must be of explicative kind, as indeed any other definition. 4 Marias, J. (1967) History of Philosophy, translated by Stanley Appelbaum and Clarence C. Strowbridge, New York: Dover Publications, pp. 62 - 65. 5 Ibid., pp. 213 6 Quine, W. V. O. Epistemology Naturalized, in Kornblith, Hilary. Naturalizing to be about, Gilles Deleuze, insisted that the chief task of philosophy was the creation of new concepts, not the development of metaphysics or epistemology. Drawing from a similarity of Quine and Deleuze, namely, the fact that they both acknowledge a special role human language (or rather the conceptual apparatus in the case of Deleuze) plays in knowledge, we could label the third “era” “conceptual.” From now on, we will be looking exclusively to the conceptions of philosophy assignable to the third “era,” because the Deleuzian conception we are dealing with belongs to it. III. A comparison of Isaiah Berlin and Gilles Deleuze Having clarified the sense in which we are talking about definitions of philosophy and introduced the main “eras” of dominant conceptions of philosophy, it is high time we started dealing with Deleuzian conception itself. Perhaps the most clear and convenient way of introducing the Deleuzian conception of philosophy would be to compare it with a similar, but nonetheless different conception. The conception of Isaiah Berlin is one of the most suitable for this task. It is better to overview Berlin's conception at first7. The philosopher distinguishes amongst three kinds of questions: factual (e. g. “Where is my coat?”), formal (e. g. “Is Fermat's Last Theorem true?”) and philosophical (e. g. “What is consciousness?”). Factual questions are those the answer to which is established by observation or empirical testing, whereas the answers to formal questions are always determined by a recourse to some formal discipline or pure calculation. (Although Isaiah Berlin has doubts about the dichotomy between empirical and formal statements and hence states that there is no strict division between factual and formal questions, he nevertheless admits that the distinction is precise enough not to be completely misleading.) The most important common feature of factual and formal questions is that these questions themselves point to the methods we ought to use or the ways we ought to proceed in to answer them. Then philosophical questions, as you might have rightly guessed, are all those which have no such builtin pointers. Presented in such a way, philosophy hardly seems to be a meaningful activity, but this is not the end of Berlin's argumentation. Largely drawing from Kant, Isaiah Berlin distinguishes between the “items of experience” and the ways in which they are viewed, “categories in terms of which experience is conceived and classified.” Subsequently, Isaiah Berlin points out the chief purpose of philosophy: to reveal what is obscure or contradictory in the terms, categories and models in terms of which human beings think or classify their experiences. So, to generalize a bit, the subject-matter of philosophy is precisely those categories or models, and the task of it is the clarification of obscurities or elimination of internal contradictions implicit in the frameworks of sciences or dominant ways of looking to the world. Such are Berlin's views on the nature of philosophy. With which of Berlin's points would Deleuze agree and which would he dismiss? There are three important Berlin's statements which Deleuze would for sure reject: 1. Berlin openly borrows his conception of “categories in terms of which experience is conceived and classified” from Kant, who endorsed the subject-object dualism. Moreover, Berlin does not explicitly deny the validity of subject-object dualism. This suggests that Berlin is content with it. On the other hand, Deleuze distances himself from this dualism because, to describe the proper place of the subject-matter of philosophy, Deleuze invents his own metaphor of space between territory and earth Epistemology. Boston: MIT Press, 1994. pp. 15 – 31. 7 Berlin, I. The Purpose of Philosophy, in Berlin, I. The Power of Ideas. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2002. pp. 24 – 36. without using any Kantian notions8. 2. When talking about the purpose of philosophy, Berlin puts an emphasis on clarification and the elimination of contradictions. However, Deleuze believes the chief task of philosophy to be the creation of new concepts rather than simple clarification of the existing ones. In fact, Deleuze draws a line between philosophy and sciences by denying the need of philosophical reflection on the sciences9, whereas Berlin thinks the frameworks of sciences should be amended by philosophers. 3. Berlin defines philosophical questions as all those containing no clear pointers to the methods of answering them. While Deleuze might agree with Berlin regarding the nature of philosophical questions, he would criticize the manner of speaking employed in this definition. For the notion of “containment” would most certainly appear suspicious for Deleuze. This is due to the fact that the main point of Deleuzian metaphysics is the denial of the existence of unities. For Deleuze, there are no unities capable of “containing” something in them; throughout his work, Deleuze stresses on the exterior nature of various qualities of things. This point might appear marginal, as it only touches Berlin's manner of speaking, but it actually is very important, because it shows one of the main points of Deleuze10. Having clarified the points where Deleuze denies Berlin, a certain question arises naturally. If Deleuze disagrees with Berlin regarding both the subject-matter of philosophy (in (1)) and the task or purpose of philosophy (in (2)), what similarities could their conceptions of philosophy have? We could formulate the similarity of their positions as follows. Although, as (3) indicates, the metaphysics employed by Berlin is completely different from that of Deleuze, their conceptions of philosophy would be indistinguishable if they were expressed in broader, “metaphysically neutral” terms. Here is a proposition which both thinkers, it is possible, would willingly accept: Philosophy is the discipline which amends the ways in which people view the world. It is easy to see how this broad and vague definition could equally well summarize the positions of Berlin and Deleuze. IV. The meaning of the quote In the light of all that we have discussed, we can finally attempt to decipher the quote from Deleuze's and Guattari's book. Talking crudely, the quote simply expresses the main point of Deleuzian conception of philosophy which we have already discussed in the previous section of the essay. However, there are some technical details in the quote worth noting, as Deleuze's language is highly metaphorical and filled with neologisms. 8 Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1994) What is Philosophy?, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 85. 9 Ibid., pp. 22 – 24. 10 See the entry on Gilles Deleuze in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessible at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/deleuze/ (last accessed 12:00, 10th of August, 2012) A few notions specific to Deleuze are used in the quote, namely, “a point of detail,” “condensation,” “components,” “concepts.” Before being able to claim to understand the quote, we are bound to find the meaning of each of these terms. Deleuze defines the concept as a point of “survey” which holds together the components of itself11. Speaking in Deleuze's metaphorical language, the concept is the point which constantly traverses its components at an infinite speed. Therefore, the concept is infinite by its speed (though finite by the contours of its components). It is “thought operating at infinite (although greater or lesser) speed.” In fact, there is little difference between terms “condensation” and “concept,” they seem to be usable interchangeably. As far as the components of a concept are concerned, they can themselves be other concepts. An important point to stress is that the components of a concept are indistinguishable: though they are different from each other, they are connected by “zones of neighborhood” or “thresholds of indiscernibility.” The point of stressing the indistinguishableness of components of concepts was to distance concepts from simple sets of things (in the mathematical sense of the word “set”), which should have been important to Deleuze. At last we are ready to state the precise meaning of the quote. Having stated the meanings of “concept,” “condensation” and “components,” it becomes pretty obvious that the second part of the quote or, to be more precise, the phrase the development of a point of detail that produces a new condensation, that adds or withdraws components points to the moment of a change of a concept. That is, it describes the moment when an old concept is being changed by a new concept or “condensation.” Therefore, the quote we were dealing with, if expressed in broader, simpler and “metaphysically neutral” terms, would look similarly to this sentence: Philosophers are always recasting and even changing their concepts: sometimes a change of a concept is enough. As we can see, we have just established what we claimed previously, namely, that the quote expresses the main thesis of Deleuzian conception of philosophy: the chief task of philosophy is the creation of new concepts. V. Conclusions We have given arguments for the view that there is no single and true definition of philosophy, but there exist different, competing conceptions of it. Then we divided all of the different conceptions into three groups, namely, “metaphysical,” “epistemological” and “conceptual” ones. Subsequently, we have taken a closer look at the sphere of “conceptual” definitions. A comparison of the conceptions of philosophy of Isaiah Berlin and Gilles Deleuze allowed us to contrast and sharpen differences of the conceptions and thus see each of the conceptions in more detail. Finally, we have deciphered the meaning of a highly metaphorical quote which was the topic of the essay. It might be worth noting that, it seems, the “conceptual” conception of philosophy has some primacy over other conceptions, because it is the only conception to fully appreciate the explicative nature of any definition of philosophy. Both “metaphysical” and “epistemological” 11 Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1994) What is Philosophy?, translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell, New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 15 – 34. conceptions often don't realize that a definition of philosophy is dependent on the world view the one who is defining posses. Returning to Plato's “The Republic,” we should state that, according to those subscribing to the “conceptual” conception of philosophy, there is no justification of philosophers' seizure of power. Hence, although philosophers have some power in their hands (as a change of ideas or concepts or categories or simply ways of looking to the world can change human lives and political situations), the job of ruling people should be left to politicians or other professionals of the task. Nevertheless, the concepts philosophers create play a huge role in society and sometimes might even be amongst the reasons of a revolution, as has happened twice (in France and in Russian Empire). Dominykas Milašius “Philosophers are always recasting and even changing their concepts: sometimes the development of a point of detail that produces a new condensation, that adds or withdraws components, is enough” (“What is Philosophy?” Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari) Philosophers can be affected and shaped by a variety of factors; besides society, education or mentors, time stands as one of the most important influences on the individual. Just like a programmer, a politician or a physicist, a philosopher is stuck in a vicious cycle of questions and answers, with the latter being so temporal and leaving such a wide range for being right or wrong. Just as different philosophers come to different conclusions while analysing the same problems, the same philosopher is doomed to constantly reconsider his own ideas as well, because philosophy is a never-ending journey of questions, both for the thinker himself, his characters and the society as a whole, directly related to the concept of time. 1. Conceptualization The idea of time forces humanity to try to solve the notorious dichotomy of “Absolutism Versus Relativism.” On one hand, time is seen as an absolute entity; on the other - as a relative outside phenomenon, differently perceived by everyone. As various thinkers try to analyse the features or identities of time, that’s not the abstract time they are having in mind, but the concept of time - their interpretation of the idea. As defined by Gilles Deleuze, leading contemporary French philosopher, a concept is “the inseparability of a finite number of heterogeneous components traversed by a point of absolute survey at infinite speed”1. Later on, Deleuze’s work portrays a concept as an event, rather than an essence of the object. The conclusion that follows, comprehends philosophy as conceptualization. The historic shift in the form of writing about philosophy happened when existentialist thinkers including, but not limiting to, Soren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche2 started writing about philosophy in a literary form, rather than complex terms the preceding tradition. Even before them, Thomas More in his “Utopia” and Homer in the “Odysseus,” and especially after them, Jonathan Swift in his “Gulliver’s Travels,” Voltaire in his “Candid” and etcetera - have chosen to reveal the world through the eyes of a conceptual literary character. Often, these characters are travelers, presented with certain riddles and enigmas they 1 Deleuze, Gilles; Guattari, Felix. What is Philosophy? Transl. by H.Tomlinson and G.Burchill. London, New York: Verso, 1994. 2 Concepts like das Übermensch (Nietzsche) and Don Juan (Kierkegaard) 2 must solve while traveling. The idea of conceptuality often involves the problem of infinity, because analysis of one concept usually requires existence of another concept, on which to base the idea, and so ad infinitum3. Therefore, a concept, which might be useful to employ while analysing the metamorphosis of the philosophers and their ideas, is a concept of journey. Due to the fact, that journey might be understood both as a spatio-temporally continuos action and as an infinite phenomenon, this essay will try to inspect both.2 must solve while traveling. The idea of conceptuality often involves the problem of infinity, because analysis of one concept usually requires existence of another concept, on which to base the idea, and so ad infinitum3. Therefore, a concept, which might be useful to employ while analysing the metamorphosis of the philosophers and their ideas, is a concept of journey. Due to the fact, that journey might be understood both as a spatio-temporally continuos action and as an infinite phenomenon, this essay will try to inspect both. 2. Traveler’s Diaries “I thought I had reached the port; but... I seemed to be cast back again into the open sea” Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz as quoted by Deleuze in “What is Philosophy?” Looking through a historic perspective, it is worth to inspect the pre-Socratic discourse of Parmenides versus Heraclitus. The subject of their debates was the notion of change (gr. κίυησις, lat. kinesis). While Parmenides believed that the changing identities of the universe are only manifestations of its indivisible and constant reality. Heraclitus idea sheds yet another light on the subject. What has become a commonly used proverb, Heraclitus proclaimed, that “you could not step twice into the same river; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” The main idea behind this consideration assumes the time being a superior concept and having power over the material and physical worlds. The archetype of the water (in this case - river), symbolizes not only the changing nature of matter, but vitality as well, and vitality assumes growth and development of identities. Even if the change is the only constant variable left 4, the philosophers change as well, because the philosophy is a journey of the mind and time leaves its mark in the reflecting system of an individual philosopher. Richard Rorty, a contemporary philosopher from over the Atlantic, has provided an interesting path of exploration while analysing the works of Wittgenstein, Heidegger and Dewey5. Rorty notices, that in the journey of their lives the approach to the philosophy of the above mentioned thinkers has shifted from the constructive and structural Kantian conception, to a more 3 “Concepts extend to infinity,” note Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in “What is philosophy?” only thing constant being change” is often regarded as a solution, considered to solve the dispute between Parmenides and Heraclitus. 5 Rorty, Richard. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature 4 “The 3 therapeutic and edifying approach6. This shift reveals the realisation these thinkers overcome - that the essence of philosophy is an individual journey of the mind; thus, the purpose of a philosopher is not to travel the journey for the reader, but to guide him gently and show the questions worth considering. Furthermore, the purpose of a philosophical work then is not to be scholastic to be read and memorised as a bible, but rather to be lived and interpreted - as a travel diary. The metamorphosis of these personas sends a clear message, trying to help people escape the temptation to seek for meaning behind everything; it only shows, that there is no truth just the quest for it. 3. A Never-ending Journey 'I think you might do something better with the time,' she said, 'than waste it in asking riddles that have no answers.' Alice in the Wonderland, Lewis Carroll A concept of “diary” implies a chronological sequence of events. But what if philosophy and therefore a concept of journey - is to be perceived not as a hierarchical structure like an upgrowing tree, but as a rhizome with an infinite number of variables, where the stems might grow in an unpredicted manner? That is the objection that Gilles Deleuze presents to the Philosophy of his time. Deleuze builds up on the age-old Fletcher’s paradox, introduced by another preSocratic thinker Zeno. The paradox assumes that at every given moment, the arrow cannot be where it is not, because no motion is occurring; yet at the same time, it cannot move to where it is, because it is already there. The conclusion can be drawn, that at every single moment, no motion is occurring and therefore motion is impossible. It seems that Deleuze tries to build on this presumption and claims that experience does not have spatiotemporal coordinates - it is infinite. Interesting to note, that Lewis Carol, a professor of Logic, has also inspected the idea of non-temporal experience in his book “Alice in the Wonderland.” In the book, Alice is stuck in an underground labyrinth there is no certain way out, the time has stopped - the clearest evidence of this is Mad Hatter’s Tea party, which is a never-ending one. The analogy of labyrinth might be interpreted as Deleuze’s concept of a rhizome - a non-hierarchical structure. The lessons behind the children story include a moral, that a journey is not a simple trip from A to B, but a growth of a person, which is not simply defined by assigning temporal identities. The same conclusion is reached by Voltaire in his satire “Candide,” 6 Most notable change has probably happened with Wittgenstein completely changing his concepts in the latter work “Philosophical Investigations” in comparison to the earlier “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus” 4 where the main character - Candide - travels around the globe and spends years while traveling just to find out, that the Philosophy cannot answer all the questions. As he changes, he realises that happiness is keeping "free of three great evils: boredom, vice and necessity7" - an answer he could have gotten without having to step out of home. These two conceptualized characters illustrate the idea, that journey matters not as a trip defined by time and space, but as an ever-lasting phenomenon. 4.A Thriving Society “There is no history of mankind, there are only many histories of all kinds of aspects of human life. And one of these is the history of political power. This is elevated into the history of the world.” Karl Popper, “The Open Society and It’s Enemies” When considering the effects of time on the society, the two are inseparable, for the development of the society and culture as a whole is only possible over time. Due to the changing variables - individuals constituting the society and the politicians architecting it, every society is living a cycle, or a journey. Historically, George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel has presented the concept of Geist - the movement of the society to the the greatest goal through the infinite mechanism of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. As the society develops, so does every concept born in it. An Austrian sociologist and philosopher Karl Popper has extended this idea by applying the concept of competition8. His conclusion describes the verification process - a mechanism, through which a concept might become a general truth. This mechanism is only possible in an open (pluralistic) society, where constant argumentation is going on. Instead of assuming everything to be true, Popper invites everyone to consider everything being false, and according to him, this method of falsification promotes argumentation to prove a certain concept to be true. Thus, as the society changes, the demand for different concepts varies and so their existence or change is defined by the mechanisms of the society. Conclusions Summa summarum, this essay has concentrated on the three levels of influences, which might foster change. “Candide, ou l'Optimisme”. Popper “The Open Society and Itʼs Enemies”. 7 Voltaire 8 Karl 5 1) Individual level. Philosophers change, because their approach to philosophy and attitude changes. Due to subjective journeys, their stories (and diaries) change. 2) Level of characters. Characters change not because the time requires them to change, but because an infinite inside journey of experiences helps them to develop. 3) Societal level. As the society changes, the concepts within it change as well, due to the demand and local mechanisms of falsification. These three levels show that Philosophy itself is a journey of questions. As every journey, Philosophy meets new challenges constantly. With these obstacles on the road, philosophers are forced to recast and even change the concepts, because certain consequences require adequate solutions. Austėja Masliukaitė 2012 'Philosophers are always recasting and even changing their concepts: sometimes the development of a point of detail that produces a new consideration, that adds or withdraws components, is enough' (G.Deleuze) There is a great importance regarding the relationship between philosophy as a scientific subject of interest and the ability to form a personal point of view by using the learned material. Although it is rather illogical to say that 'now' is the time, when we have already reached a completely independent state of a human mind (as independence as we know it is also just a concept of our society), we can attempt to view the horizon of philosophical evolution more independently than before 'now'. This also means that the personal point of view, formed by understanding of previous theories of knowledge or being, is to be far more paradoxical, therefore meaning that having a subjective opinion to phenomenons especially in the 20th century, some time after revolutions, psychotic wars and human destroying ideologies, was basically understood as simply another view and not as a next step to overall thinking of the human race. Hence, being shaken by a harmful and prevailing control of human perception, philosophy had to be viewed at from a different angle. Previously, philosophical theories were often embodied in subjective situations (where they were convenient). Naturally, finally having in mind that there is no absolutely right point of view, somehow the universal ground of philosophy had to be formed. At this time, constructivism could be finally used to explain the way of thinking and the substance of thought. The basic idea of constructivism is that the being of every particular thing is defined by its reactions and relations to other things. The 'atom' of constructivism might be the concept, but the main principle is that it reflects in every situation regarding different phenomenons in the whole reality. Most importantly: a person is learning according to the relations between his previously gained information, so every learning is subjective. Learning here should not be understood only by learning of particular disciplines, but more as the existance in life as a social personality. One of the founders of constructivism, russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky states: 'Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological).' 'Child' here can be replaced by simply 'human', as an example of child's interaction with the world is just a way of expressing more general, less subjective relation to things. This leads to Vygotsky's social development theory: 'Social interaction plays a fundamental role in the process of cognitive development' . This is why after experiencing revolutions, fascism, communism, repressions etc. we (separate individuals) are not able to hold both logical and subjective point of view regarding our current world. Moreover, if we are talking about usefulness, meaning and future of the whole philosophy, we might come to a dead end. However, this is why constructivism is though to be adaptable in a proper way: it comprises all parts of overall human being. Having that in mind we can now focus on Deleuze's thought. It is of great importance to state the primary view of Gilles Deleuze regarding the history of philosophy: 'The history of philosophy has always been the agent of power in philosophy, and even in thought. It has played the repressors role: how can you think without having read Plato, Descartes, Kant and Heidegger, and so-and-so’s book about them? A formidable school of intimidation which manufactures specialists in thought – but which also makes those who stay outside conform all the more to this specialism which they despise. An image of thought called philosophy has been formed historically and it effectively stops people from thinking.' This is the way to talk radically about the historians, because as a discipline, philosophy is nothing but a pile of information of the past events and thoughts of past-lived people, which inevitably eventually leads to perceiving that in that sense 'philosophy is dead', again, due to the fact that our 'now' doesn't cohere with rightness of subjectivity anymore. However, Deleuze interprets other past philosophers (Hume, Spinoza, Nietzsche), writes on their past theories and thoughts. If that is not adaptable (in time of 'now'), not modern enough, why did he still do that? This is where all falls to its places: although clinging to one philosopher or one theory is yet completely useless, the importance is the new concepts that are formed by reading those past texts. For Deleuze, the whole point of philosophy is to form those new concepts. This is how a specific science logically gains meaning by producing individual thought and also continues the same process to the future. Only with this cooperation, the philosophy (meaning it generally, both by history and perception theory) is not dead, and is never to become dead. This is an actual reflection of constructivism, because according to Deleuze (and Vygotsky), a philosopher here is a learner, who forms his point of view by adapting his previous knowledge and this (if he is an actual philosopher) then helps him make new concepts. Deleuze admired Spinoza because he saw him as a pure subjectivist. As Spinoza states, there is only one substance, God or Nature. Furthermore, there is nothing transcendental, as the perception of something above our point of view is actually 'made' of a same substance and is analogically subjective, meaning that everything is basically subjective. This interpretation of Spinoza helps Deleuze greatly prove and establish his own theories, based on constructivism. This way Deleuze develops his thoughts much further. The concept (as the 'atom' of existence of human mind and world) is defined by its possible world, existing face and real language or speech. This is how you can explain the ever-lasting subjectivity of phenomenons. Possible world is all the potential faces of the objects (ways it can be seen by every single individual), and the real language or speech criterion adapts it all to our society. Owing to this, we can better grasp Wittgenstein's ideas, because as the language is one of the main parts of the concepts of life, there is no doubt that society has formed itself in a natural convenient way and there is no need to question our reality, as it is an outcome of all our historic human life concepts. But what is the point of all this eventually? If we admit that every concept has a different subjective face (although shaped by social language context), we state, that concept is not definite. It is actually similar to a physical atom. The idea of the concept is like a nucleus of an atom, and the existing face of the concept is like an electron, whose position in an actual atom cannot be stated. We can only predict where an electron is more likely to be at a particular moment, and the totality of those positions form a potential uncertain shape of the atom. The concept, similarly, is also a shape or a volume, formed by every single personal perception (existing faces). This is why philosophers are always recasting and even changing their concepts. In this way, the core idea is the same, however, by changing or developing a point of detail, a new consideration is produced, which helps understand the concept not from one existing face, but from more, forming a broader opinion, more open mind of a philosophy reader. This doesn't mean that philosophers in the past had thought it all through to the future, the majority of changes of concepts' details were most likely unpredicted. But this only helps the nowadays philosopher acquire more philosophical knowledge. It may seem as a drawback if we looked at it only from a historical angle, however, as stated in the beginning, the philosophy without consequential formation of new ideas is nothing. We all now have an inevitable a priori opinion to all social or political situations, theories as our culture and history tell us that. So again, it might seem not rational to read particular philosophers, as their concepts are historically subjective, not to mention, they (as said before) might even change overtime. Nevertheless, Deleuze's theories and opinions leads us to an outcome, that precisely the movement, the alteration of philosopher's concepts reveals us a significantly broader understanding. Therefore, knowing a huge number of philosophers' theories may not make someone a better philosopher than deeply focusing on a few and creating personal concepts of though.