Open

advertisement

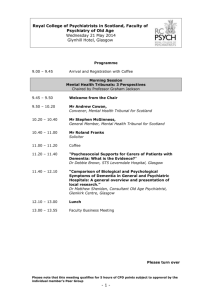

Feedback note of the Seminar on “Public Sector Residential Land Disposal and Development” Date: 23rd June 2009. Venue: University of Stirling, Stirling Management Centre. Programme: See Appendix 1. Participants: See Appendix 2. Speaker Biographies: See Appendix 3 Links to the Powerpoint Presentations: See Appendix 4 This event was hosted by Scottish Government and Homes for Scotland and supported by the Association of Chief Estate Surveyors (ACES) 1. INTRODUCTION This event asked how the component organisations involved in residential development could help unlock the potential of public sector land and help maximise new houses building in a turbulent market where little speculative development is being financed. These are testing times for those involved in the disposal of public sector sites. The housing development community needs to ensure that it has the best information to aid successful acquisition or disposal. This conference was an opportunity to hear the latest thinking on disposal techniques. Key topics covered included: an overview of current practice; the potential for Development under Licence, Development Agreements or Long Lease Agreements and innovative joint venture arrangements to facilitate disposal and subsequent housing development on publicly owned land. The benefits of attending the event included: the ability to gain key information and learn from best practice examples across the sector; develop understanding of how the financial markets impact on this work and to provide useful networking opportunities. This note provides a resume of the presentations made on the day, it highlights the issues that arose and notes the future action intended to address them. 2. RESUME OF THE PRESENTATIONS A. Frank Sheridan (The Council Perspective) Frank identified 3 main delivery mechanisms involving deferred payments. (i) Development lease This is normally a 175 year ground lease with provision to build within 7 years. The 175 year period satisfies lenders requirements for loan security. It is normally for commercial developments (they have only one residential scheme) receipts can be taken as a lump sum upfront, as rent and profit share. It combines upfront and deferred payments and can include an overage payment secured at end of the period. Developers like it because it involves less cash upfront. As parts of the scheme are built out they move onto a feu disposition which takes it out of the lease. The lease normally specifies a full master plan, development plan specification is also is in the lease together with timetables and milestones. (ii) Development agreements The example quoted was Drumchapel involving 8 sites and potentially 1400 houses, all of which are non-affordable. The developer draws down particular sites as required. Glasgow Council retains ownership throughout the scheme and developers bid on the basis of a detailed document, a detailed infrastructure, specifications etc. The whole scheme needs to be very flexible as the planning basis of the initial agreement may not be realised so terms need to be flexible. The developer never actually owns the sites. This involves a significant resource commitment of technical staff plus a close and sympathetic relationship with the local planners that is a strength in local authority led initiatives. (iii) Partnership This is a relationship between 2 or more distinct bodies coming together in a partnership to create a distinct entity – a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to undertake a particular project or set of projects. The example was working with British Waterways and ISIS. The focus of the work is the Glasgow branch of the Forth Clyde Canal where the Council and British Waterways have control over much of the land. Glasgow Council put the land into the pot together with British Waterways and the arrangement is that ISIS has first refusal as a developer on any schemes. Control is maintained by the fact that either partner can veto any proposal. The agreement includes profit sharing, development proposals, fixing targets, cash flow, and investment funds. The partnership offers flexibility. The partners’ master plan the schemes, coordinate community involvement and these are very big upfront investments in terms of time, staff and resources. They consider it pays off. Cash flow stays within the project but the council does take out a percentage of the value. Some of it goes into a canal investment fund for reinvestment in bridges, locks, tow paths etc. This scheme works because officials have a large degree of flexibility to work within broad Heads of Terms that the council have approved. The Heads of Terms give comfort to both parties but plenty of flexibility. Glasgow Council assesses best value by assessing the residual value of the land but includes externalities like improvements to employment, council tax revenue, and presumably reduction in vandalism, costs of fly tipping, litter etc. It is a holistic appraisal. B. Charles Church and Steven Tolson (The Developers Perspective) Developers are largely dependent on bank lending but even those with cash resources are being extremely cautious regarding risk. Previously they were willing to take a long-term view and pay for the cost of remediation and infrastructure to prepare large sites and then embark on a rolling programme of development. They are no longer able to incur the significant upfront cost of improving land by infrastructure and remediation. Similarly, they are now seeking to offset obligations to incur costs in advance for Section 75 agreements. Developers now lack money and cannot lay money out at the start. They also have significant difficulty dealing with risk Gladedale have been involved in Oatlands by the M74 near Shawfield south of the Clyde which they have taken on 175 year lease from Glasgow Council. The site has flood, contamination including chrome and other difficulties. They set up a sinking fund and a third of this can be drawn down by the developer, one third by the council and one third for the project. It is a 5-8 year programme for around 1200 houses and this is likely to be extended over a longer period. He agreed with Glasgow’s 3 deferred receipt disposal methods – long lease – licence agreement, JV etc and commented that long leases are available to their bank. Steven asked a very pertinent question as to what sectors of the market will remain active, which banks will actually lend consumers money, which banks will lend developers money and how will the value of the land be calculated. He thought there should be deferred payments and he was very keen on sharing profits and risks. He wanted the public sector to share in risk. He claimed that the public sector has not participated in risk for years and referred back to the days when the public sector “created places” and house builders were merely technicians who built houses within a framework of places. He alluded to the Scottish New Town Development Corporations, URCs and the Crown Street redevelopment. He thought there would be great rewards for the public sector and held up as examples EDI and Edinburgh Park, Fusion Assets (now wholly owned by North Lanarkshire Council), Stirling Development Co (Valad and Stirling Council) though he thought that the Council was taking more risk by placing most of its development assets with one partner. D. Paul Warner and Alasdair Fleming (Legal Perspective) Paul highlighted some areas of legal difficulty which often confront public authorities when selling land for development. Since the purpose of the conference was to explore how we can remove or abate factors which can hinder housing regeneration, Paul made some recommendations for legal changes and suggested the use of certain legal methods which he believed would simplify the process of achieving land sales and worthwhile development. I will also refer to some legal protections which the selling authority will wish to put in place when disposing of its surplus land for housing purposes. Legal Constraints Although, generally, private individuals and corporations can dispose of their land in any manner they think fit, this wide discretion is not open to public sector bodies which are under a general duty to preserve the public purse. The law affects how public bodies should choose purchasers of land for development and the level of price which an authority can accept. I will therefore briefly mention the constraints of procurement law and the law relating to the price which a selling authority should expect to receive. (a) Procurement For years, it was thought that when a public body disposed of land for development, such a disposal would fall outwith European procurement law. Even where a disposal by an authority involved an element of works to be undertaken by the developer which would then be returned to the authority upon completion, this ‘ancillary’ procurement of works would not be trapped by the procurement law if it were not the main purpose of the transaction. That view no longer applies since the judgement of the European Court of Justice in Auroux v. Commune de Roanne, a case decided at the beginning of 2007. In that case, the court decided that the EU procurement requirements apply to a contract between a regulated public body and an economic operator where (i) the development is to provide an economic or technical function and (ii) the development meets a specific objective of the public body. The public works in the Roanne case related to the provision of a leisure centre and this was held to perform an economic function. As for meeting the specific objectives of the disposing authority, this need not be in terms of a detailed specification – simply being in conformity with the authority’s policies for regeneration can be sufficient for the proposed procurement to fall under EU law. It is questionable as to whether the construction of housing alone performs an economic or technical function and, to that extent, the Roanne judgement may not apply to disposals for the development by a third party of housing only, but this position is uncertain. However, a development agreement which involves a disposal for mixed use including housing might well be caught by the principle in Roanne and this will require the disposing body to follow the requirements of the procurement regulations. Such requirements could seriously limit the disposing authority’s ability to deal with potential developers off-market. So, a public body with surplus land to be sold for housing development may well require to adopt formal procurement procedures and advice should always be taken from procurement lawyers for this purpose. (b ) Constraints affecting price The next legal constraint I wish to highlight is the suite of statutory provisions which require a disposing authority to obtain a certain level of price or consideration. As a former local government lawyer, section 74 of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 immediately springs to mind since it prohibits local authorities from disposing of land at less than the best consideration which might reasonably be obtained without the approval of the Scottish Ministers. That is a general duty but there are additional specific provisions too. Under the Housing legislation, not only is there a duty to obtain best consideration, but sale of land held on the housing revenue account will quite separately require the consent of the Scottish Ministers. Where land is held by a planning authority for planning purposes, a different statutory regime applies: here, the authority must obtain either best price or best terms which can reasonably be obtained but, unlike the general provision under section 74 of the 1973 Act, and the housing legislation, there is no power to dispose of land at less than best price or best terms even with the consent of the Ministers. There are no similar statutory provisions which govern the sale of Crown land, that is, land held by central government or the Scottish Government but guidance requires all surplus land to be disposed of preferably by competitive bidding in order to obtain best price. The main constraint as regards the price therefore applies to local authorities. The problem, if any, is the uncertainty which arises when a local authority proposes to deal off-market with a developer, usually for very good reasons, for example, where the developer already has a significant landholding in the area and is in the process of preparing a planning application. If that developer intends to use the local authority’s land for a relatively low value use, for example, for landscaping or open space, the value of that land might well be less than the best consideration which the authority could obtain if it sold the land separately, say, for retail – or housing (assuming the presence of a buoyant housing market). Such a transaction would inevitably require the consent of the Ministers but, if the land is held on the planning account, there is no facility to obtain the consent of the Ministers (or even the consent of the court) to such a disposal. Where the authority’s land is not held for planning purposes, the requirement to obtain ministers’ consent to a disposal is not usually a significant problem since the turnaround time for obtaining consent is generally within a month. However, The risks in relation to the sale of planning land are much greater and the authority must be sure of its position before proceeding to conclude a transaction. The statutory Best Value regime, introduced by the Local Government in Scotland Act 2003, intends to amend section 74 of the 1973 Act to make it a little easier for local authorities to demonstrate that they are obtaining best consideration but the amendment has still not come into force some six years after the passing of the Act. I think after six years, it is about time the legislature either brought the amendment into force or announces its intention to abandon the amendment. Note also that the best value amendment only alters section 74 – it does not deal at all with similar provisions in other legislation and, in particular, not the especially restrictive duty in relation to planning land. You must bear in mind that if a local authority does breach these rules, and this is successfully challenged in the courts, the sale transaction is set aside as void. The risk of this should certainly not be assumed by developers and lenders, let alone by the selling authority. I would therefore recommend that the best value amendment to section 74 be implemented quickly and that similar statutory provisions in relation to disposals of local authority land should be repealed. (c) Common good land While we are on the subject of legal constraints, I would recommend that the status of common good land should be abolished since its concept is anachronistic and unnecessary. The discovery of the fact that local authority land intended for development is inalienable common good land can prevent a transaction from completing where there is no time to obtain the court’s consent to the disposal as is required by law, for example, where it is critical to complete a disposal to a housing association by the end of the current financial year. The abolition of the status of common good land would be in line with the modernisation of land law brought about partly by the abolition of the feudal system a few years ago and it is suggested that abolishing common good status would be relatively simple to achieve. Imposing Development Conditions This conference is about promoting and enabling deals which result in the provision of housing. It is therefore critical, if this objective is to be met, for the selling authority to retain some degree of control over the development of the land being sold to ensure that the development takes place as envisaged and within agreed timescales. Otherwise the authority’s property might simply be land-banked. Isn’t this not the role of planning conditions and building standards? Not always. The legitimate economic and social aspirations of the selling authority may well be more detailed than anything which can be made the subject of planning conditions and, of course, it is always open for any person in the future to apply for a change to the planning permission. This then requires that the conditions relating to the nature and timescales of the development be set out in the contracts governing the disposal, which usually take the form of a development agreement and consequential conveyancing documents. The need to impose these conditions also influences the legal method of disposal. The purpose of the development agreement is to capture the whole terms of the deal reached between the selling authority and the developer. It contains the clauses you might expect to find in missives of sale and ties together what is to happen before entry is taken by the developer, how the property rights are to be granted and what is to happen during development and thereafter. The legal problem which arises here is that a development agreement, like any other contract, is only binding on the parties who sign it. So, what happens if a developer gains ownership of land and then sells on or goes bust prior to completion of the development? This is where the law of property, as opposed to the law of contract, steps in. (a) Disposals by way of dispositions/Section 15 agreements Unfortunately for selling authorities, it is not easy to create lasting conditions governing development and use of property after a sale as a result of the new land law introduced in 2004. Some attempt was made in the Title Conditions (Scotland) Act 2003 to enable some public bodies to create title conditions where no land is being retained but the scope of these might prove to be restricted in operation. For example, a local authority and the Scottish Ministers may impose an economic development burden which is intended to last in perpetuity but such a title condition only applies to a condition which is intended to promote economic development. My own view while at Glasgow City Council was that an economic development burden could not be imposed in relation to land to be used for the development of housing since the resulting use would not be business or economic use. That interpretation seems to have been adopted in the first case which has discussed economic development burdens, Teague Developments Limited v. City of Edinburgh Council, a case which came before the Lands Tribunal for Scotland in 2008. The title conditions in that case involved a restriction of use for general industrial purposes with certain specified qualifications. The determination of the Lands Tribunal in holding that these conditions promoted economic development suggests that some kind of business use of the land is required for there to be economic development for the purposes of creating an economic development burden. A housing estate clearly falls outwith the scope of this new statutory form of real burden. For that reason, a straight sale of land by an authority implemented in the usual way by granting a disposition is not attractive for the purposes of having some say in what happens once the developer has gained entry – unless an additional special statutory contract is entered into. This special contract is the section 15 agreement – this refers to section 15 of the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 in terms of which the local authority, as housing authority, can seek to regulate the use of land being sold by it, as well as other land owned by the developer, for the purposes of the development of housing. This agreement is registered in the Land Register and thus becomes binding on whoever comes to own the land in future. It is like a planning agreement under section 75 of the Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 but, unlike the section 75 agreement, it is not susceptible to discharge where planning permission is obtained for another use or development. So, if you represent a local authority which typically sells land by way of a disposition, I would recommend that you use section 15 agreements if you are not already doing so. (b) Disposals by way of licence agreements At the other end of the disposal spectrum, we have the licence for development. A licence is a synonym for ‘permission’ – the landowner grants permission to the developer to take entry to the land for the purposes of carrying out the development. Upon completion, whether or not in phases, the landowner is contractually obliged to pass ownership to the developer or, more usually, to third parties nominated by the developer (the house buyers). We used to do many licence agreements for the development of housing at Glasgow City Council. Sometimes, the developer would pay a premium upon taking entry to the site at the outset but the consideration payable to the Council would usually be in the form of a licence fee which would be paid to the Council in instalments on the sale of each residential unit to a house buyer. The beauty of the licence agreement from the Council’s point of view was that the Council remained the landowner of the land still under development and, if there was material breach of the licence agreement by the developer, or if it went bust, the Council could remove the developer and either procure a new developer to complete the works or even complete the development itself. However, the model of the licence agreement became less popular, particularly since the turn f the century, as lenders increasingly insisted on obtaining a standard security over development sites in respect of their loans to developers. As self-financing of development also became less usual, the use of licence agreements for development became rare. I very much doubt that the licence agreement model would be used by anyone in the current economic situation where development funding is not easy to obtain and where developers are not exactly rolling in unused capital to be in a position to self-finance. (c) Disposals by way of lease with an option to purchase Since a straight sale is not particularly attractive to a selling authority (at least where the development is to be for mixed use including housing), and a licence is not attractive to developers and their funders, there has to be something in the middle which is just right – the ‘Goldilocks’ model of disposal. This is the grant of a long lease by the authority incorporating an option to purchase in favour of the developer. This mechanism satisfies some fundamental requirements:- the selling authority retains the ability to enforce development conditions during the lease since it is the landlord; if there is a serious enough breach of the lease by the developer (who is the tenant), the landlord authority might be able to terminate the lease and replace the developer; unlike with the licence, the developer obtains property rights as tenant and, in the case of long leases, the lease is registrable in the Land Register which then enables the developer to grant a standard security over the development site in favour of the funder. The development agreement which is the over-arching agreement between the selling authority and the developer, as well as the long lease itself, will both contain provisions which allow the developer to purchase the authority’s ownership of the site once the development has been satisfactorily completed. If the full price for the land has already been paid at entry, or in earlier phases, this final stage when the developer takes ownership usually does not involve the payment of any price. This option to purchase procedure can be flexible – as with the Oatlands development in Glasgow - it can be staged in phases or even on a residential block by block basis with completed blocks or sites cut out of the lease as ownership passes to the developer. Site Assembly and Compulsory Purchase Orders I could cover this topic in significant and mind numbing detail but lack of time has spared you from this. What I would point out is that local authorities, as housing authorities, are in a position to use powers of compulsory purchase, not only for their own housing developments, but also to assist third party developers who are unable to complete their site acquisition required for a development. It depends on the nature of the deal whether the developer is to reimburse the authority for the whole costs of promoting the compulsory purchase order and the compensation payable to proprietors but the legal contract, the back-toback agreement between the authority and the developer governing what is to happen is a tried and judicially approved mechanism for governing the use of a CPO for the benefit of a developer. Glasgow City Council has developed a template back-to-back agreement for this purpose and copies have been made available to other local authorities through regular meetings of local authority property lawyers. Although the back-to-back agreement is a stand-alone document, its provisions can be incorporated into a development agreement where the promotion of a CPO is required to facilitate a larger transaction involving disposal of land by the authority. Deferred Payment of Price There is nothing new in the concept of a purchaser of land paying the price, or part of it, either by instalments or on the occurrence of some future event. In addition to the idea of delaying payment of the price, there is also the mechanism of profit sharing. Although there are many ways in which the payment of price can be deferred, I will deal briefly with three principal methods in turn. (a) Instalment payments Instalment payments are easy enough to understand – the whole price can be agreed at the outset and instalment amounts and dates for payment are written into the sale contracts. As with the imposition of development conditions, the most advantageous model from the authority’s point of view is to have the instalments linked to phases of the development so that land is only released to the developer once planning permission for that phase has been obtained, the developer is ready to go on site and the instalment for that phase is paid. This process can be made more flexible in a phased release where the parties agree to negotiate the price for each successive phase at the time the developer is ready to take entry. Of course, in the absence of agreement as to price, the contract should provide for third party determination and the basis of valuation should be clearly set out in the development agreement to avoid time consuming squabbles. (b) Clawback A second model for deferred payment is the situation where there is a quick sale of the land, with or without payment of price at the outset but providing for a further payment to be made if a specified event occurs – for example, the developer obtains detailed planning permission for a development the detailed nature or scale of which is not clear at the time of purchase. In this scenario, the grant of planning permission would either trigger the payment of a known sum, or a sum which can be calculated with reference to the number of housing units for which planning permission has been obtained, or the parties can negotiate an uplift in the value and refer the matter to a third party where there is a dispute. This kind of deferred payment is called clawback and it should not be confused with overage which is another term for profit sharing. (c) Overage The third model, the payment of overage, is really the sharing of surplus profit made by the developer since it is usually the case, but not always, that the developer will want to take the developer’s return, a percentage of development costs, before any further profits are shared with the selling authority. Overage provisions were very popular with selling authorities during a rising market since developers often underestimated total sales receipts and it remains to be seen when overage becomes a viable concept again when the economic recovery begins. At Glasgow City Council, the payment of overage was usually required as a matter of policy where land was being sold off-market. The sharing of surplus profits helped the Council to ensure that it was obtaining best consideration in a situation where exposure to the market had not occurred. As with the Oatlands project itself, overage can also be used as the only means of obtaining a price where the land has little or no value itself; perhaps due to the cost of demolition, site clearance, flood protection measures and ground remediation works, such as the removal of contamination. However, in a declining market, reducing the initial price in the hope of receiving overage upon completion of the development may not be a good idea if the developer struggles to make any real profit at all. Such an arrangement might well offend against the legal duty to obtain best consideration. (d) Security for deferred payments It goes without saying that where the authority’s land has been sold or leased to a developer where any part of the price or overage is payable in the future, there has to be some security for this liability to be granted by the developer in favour of the public body. Obtaining a security in the form of a standard security is generally not a problem but ranking of this security as a first security can cause problems for the developer and their lenders. I have always taken the view that payment of instalments and clawback require a first ranking security in favour of the selling authority. After all, if all of the price were to be paid at the outset, then the seller has received all of the price in preference to any sums due by the developer to the lenders. By arranging for the price to be paid in instalments or by way of clawback, the seller grants a concession to the developer and it is only right that the seller should receive its full price before the purchaser pays off its loan. The position is a little different in relation to overage where a more relaxed view can be taken by the selling authority. Since overage is only payable to the authority where surplus profits are made, it is very likely that the unexpectedly high sales receipts will be used by the developer to finance its borrowing and the risk of default in relation to the payment of overage is consequently very low. Although deferred payment arrangements might seem attractive as a means of making it easier for developers to proceed with their projects without too much financial outlay at the start, selling authorities must be mindful of their legal duty to obtain best consideration and these deferred payment mechanisms should be negotiated on a strictly commercial basis with proper security for future liabilities. Disposals Via Joint Ventures Finally, I turn to joint ventures. This is an area in which I have not had much experience since Glasgow City Council preferred to dispose of land for development in terms of development agreements which state in terms that no partnership or joint venture relationship exists between the parties. The development agreement approach also ensured that the developer alone was taking the business risk. The legal concept behind a joint venture is that, at least for the purposes of a specific project or projects, a new business entity is created in which the partners share an equity interest as well as the business risk. At the informal end of the scale, the joint venture will simply be governed by a joint venture agreement, which might look quite like a development agreement, but for very large scale projects, the business relationship can be formalised by incorporation into companies, limited liability partnerships and urban regeneration companies. The establishment of a formal joint venture company, though, may well have adverse tax implications for any private sector partner since income received may be taxed in the hands of the JV and then again when distributed to the JV parties. There therefore has to be a very good reason for using the JV approach and I would have thought that this is really only appropriate where a long term relationship is envisaged not usually required where housing developments alone are concerned and where a sale by development agreement might be more appropriate. Another issue to be addressed when setting up a JV, or even a subsidiary which is wholly owned by the authority, is whether the authority’s land is to be transferred into that entity. If so, the requirement to obtain best consideration still applies. The current guidance issued by the Scottish Government in relation to applications for section 74 consent make it clear that a disposal of land even to a wholly owned subsidiary at less than best consideration still requires ministerial consent. This consent is more likely to be granted where the subsidiary is wholly owned by the authority but a disposal at less than best consideration to a JV might be seen in some way as a donation to the private sector partner. Remember also that a transfer to a JV of land held for planning purposes at less than best price or on best terms cannot be sanctioned by ministerial consent. There are no such difficulties where the subsidiary or JV merely acts as an agent for the selling authority in procuring a disposal for development at market terms. Finally, to complete the circle, the authority will require to take advice on the procurement of a JV partner since, although the intended development might well be restricted to the erection of housing, what is being set up is a business entity and this is the economic function I mentioned earlier in relation to the Roanne case. Again, advice from procurement lawyers is essential here. F. Liam Fennell (The Banks Perspective) RBS has experience deferred receipts work particularly using the long lease mechanism. Property Ventures, RBS, has the mandate for equity and mezzanine finance of property projects within UK, though given the current market the emphasis is towards senior and mezzanine finance. There are relatively few funders providing mezzanine funding in the market and there is little or no appetite for speculative funding and highlighted the importance of having income producing assets. In assessing a development the quality of the partner is key, i.e. high calibre and good track record, high quality assets, and a sharing of risk and reward. He pointed out that the public sector was pre-occupied with cash receipts but he thinks that getting construction going is much more vital. The purpose of Basel II, an international banking standard about how much capital banks need to put aside to guard against the types of financial and operational risks banks face Generally speaking, these rules mean that the greater risk to which the bank is exposed, the greater the amount of capital the bank needs to hold to safeguard its solvency and overall economic stability. The impact means that funding mezzanine and equity is much more capital intensive and returns need to reflect this position. In his view the public sector can bring forward development and reduce the risk profile of projects by pulling together the initial ground work e.g. master planning/site assembly and infrastructure. Within the current environment there is a greater emphasis on the development partner putting cash equity in to projects and not relying on implied land value.. Liam touched on infrastructure fund mechanisms such as the tariff basis used by Milton Keynes, SWERDA, JESSICA and FIFF. He then mentioned 3 developments which Property Ventures has with public sector partners; the Cart Corridor where Renfrewshire Scottish Enterprise and Renfrewshire Council are working together sharing surplus income and have an option of a land that they can draw down on, Higher Broughton, Salford, a complex JV with RBS 41%, Council 19%, City Spirits 20%, He also mentioned the regeneration at Polkemmet, West Lothian. G. Allan Lundmark, (Homes for Scotland) Alan felt that Section 75 Agreements were too extravagant, often over engineered, over specified and simply unsustainable in the present climate. During the boom the housing industry was a major supplier of public sector infrastructure. He felt the public sector had to get to grips with the reality of the present situation and seemed to doubt whether in current circumstances the house builders could sustain most forms of planning agreement. He considered that the “Firm Foundations” discussion of 25,000 homes roughly represented replacement levels of housing but that he saw this year and possibly next year housing output plummeting to 9,000 units and that it could take many years before we clawback to replacement levels. He pointed out that £800 billion have disappeared from the funding market with overseas lenders with drawing from the residential market and real estate is fighting for a share of the remaining market which he estimated at around £300 billion. Even that is difficult for the construction industry as many banks will not lend to real estate. Not only is the supply of borrowing to house buyers highly constrained, but so is the supply of finance to builders. The supply of land to the house builders is also constrained. He pointed out that a 20% drop in gross development value (what the developers get for the development before the deduction of cost) has a 58% effect on land values. Land values are disproportionately affected when house prices move up or down. He made the point that the industry can build units for as little as £120,000 but what they cannot fund is the land price, and all the associated infrastructure. He put up a number of graphs which showed that the housing market is polarised between those on benefit/pension who are provided for through affordable housing, and the private house building market which deals with the financially better off. What is deeply concerning is that the gap in the middle where people on modest, medium and average incomes lie cannot quality for affordable housing and cannot afford to buy a house. Alan questioned the emphasis on large sites with huge infrastructure requirements that cannot be provided in the foreseeable future. He noted that the immediate future lies with smaller sites within the urban envelope with existing infrastructure. He also pointed out the enormous pressure that our carbon reduction programme will impose which basically means that one has to develop where there is good public transport. What Homes for Scotland would like the public sector to help ameliorate risk for developers, reduce the administrative, planning and regulatory burdens on the sector, cut costs and make procurement easier. 3. ISSUES FROM ROUND TABLE AND PANEL DISCUSSIONS. (i) Disposal of Public Land There was extensive discussion on the 1/3 “sinking fund” for market failure as used by Gladedale in Oatlands. Participants would welcome more information on how this works in practice. There is a significant role for performance bonds to cover some of the assets if developers go bust. The meeting agreed that any follow up work should look at the implications of the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 Section 15 which can record an agreement in the Land Register which is binding. There was a lot of concern expressed over the affect of the current downturn on existing development agreements. In best practice long lease arrangements values can be re-appraised as the project goes along. However, the significant drop in land values over the last year will be having an affect on existing agreements that do not have reappraisal clauses. Information on re-appraisal clause was sought. Landowners have aspirations of land value based on their asset management. There was concern that a number of owners do not wish to sell at current values and will await uplift as the market improves. There was a wish for clarity on the scope that local authorities had and were willing to take on whether to accept housing / other delivered development as their receipt rather than capital receipt. There was also discussion also around whether capital receipt income should be ring fenced for reinvestment in property. However there was a recognition that this cuts across the autonomy of local government. Could the public sector budgets be re-profiled over time to allow them to enter into JVs, etc, and share the cost of infrastructure in the knowledge that the government or the share in uplift in value of the development will replace their budgets in years to come. The developers asked for greater consistency across the different public bodies in their approaches to development and their expectations of developer obligations. There was discussion on whether local authorities sometimes apply a different policy regarding to Section 75 Agreements (including affordable housing) to central government sites than they do to local government land. Some of the developers, however, also noted that whilst the pressure on public sector budgets was acknowledged there also needed to be much more public sector led approaches to development in new models. The meeting asked for a review of different models e.g. Drumchapel, Oatlands and a comparison with the new Kick Start scheme in England would be useful to understand in more detail how different approaches and models might be developed to respond to the current economic situation. The meeting welcomed the fact that all public sector landowners in Scotland were being brought into this debate. Some Council participants were concerned that in practice Audit Scotland’s `working’ definition of best value may lead to criticism of innovative disposal activity such as the deferred receipt mechanisms. They would welcome Audit Scotland being consulted on deferred receipt mechanisms and its impact on best value in situations such as disposal at less than best consideration. There is a perception that pace of implementation and decision making by the public sector was too slow. In many cases large projects are taking too long to reach the market. Raploch implementation timescales were cited with the delay now impacting negatively on the project. It was recognised that existing positive arrangements should be better publicised, eg the Highland Housing Alliance and Oatlands arrangements. It was felt that we could do more to share knowledge on best practice. This would be in addition to the functional best practice advice that may be useful in the form of a toolkit for technical issues regarding deferred receipt mechanisms. (ii) Lending The present position seemed to be that lending institutions are seeking to de-risk investment and they are working towards a "flight to prime" / "flight to certainty of return (e.g. PPP, PFI) agenda that will see many sites not considered for development regardless of ownership. The meeting agreed that close liaison with the banking sector on this issue was necessary as the market develops. In discussion developers said there had been recent changes to or withdrawals of existing bank overdraft facilities. Often these changes are announced by the banks with only a short period of notice with the effect of undermining the viability of planned investments by developers. Where overdraft facilities have been extended these have often been provided on condition of payment of high arrangement fees in addition to rates of interest far exceeding the inter bank rate. Some banks have placed a blanket ban on issuing loans for whole categories of properties of investment such as residential development in City Centres. (iii) Legal The long lease arrangement for deferred payments best suit our highly specialised agencies and NDPBs which on the whole do not have staff resources or the breadth of portfolio to justify an SPV Head leases have proved problematic for certain local authorities in the past. It would be useful if the potential for this initiative to act as a catalyst could be investigated. There remains the issue of how the public sector would maintain its capital programme if long lease arrangements were put in place. Could the government underwrite? Would the banks be prepared to release short term funding to make such arrangements possible? There might be a case for legislative reform to allow residential leases of over 20 years, and introducing a public sector title restriction for housing to remedy the gap in Title Restrictions Bill. Questions also arose around the need for Legislation to implement the changes to Section 74 of the Local Government (Scotland) Bill. The ability of local authorities to have agreements on housing land under the Housing (Scotland) Act 1987 s15 could be extended to central government. The meeting considered tax proposals to capture uplift in land values but highlighted the difficulties England (and UK in past) has found in implementing such initiatives. (iv) Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) The meeting discussed the benefits of SPVs and urban regeneration companies. The participants would welcome more information on the performance of existing SPVs in the current market. Some developers felt that a well managed Joint Venture (JV) or SPV could continue if one of the partners went into administration. Whereas in a long lease market failure may prove to be an insurmountable problem. Some Council officers felt that their structures would work against JV involvement as their decision making processes can be slow. Others felt that this has not been a problem to date as members knew that they have to act primarily as Board Members in a JV. JVs may be best used if they had a wider regeneration purpose and the commitment of a number of partners and especially the Council SPVs also may best suit local authorities that are multi agency, and have considerable internal resources to help them staff, support and monitor an SPV. It might occasionally serve large health boards with a number of sites to dispose off such as NHS Lothian or Scottish Water. Joint ventures may seem attractive but they pose resource challenges for public bodies including URCs. This is in relation to the time involved, whether the capacity is there to participate effectively and more importantly to be able to assess and manage the risks involved. When entering into any joint venture arrangement all parties should take a long term view on the returns from this. The public sector wants its maximised return early and the developer needs to show early profit winners. However a longer term view should not be an excuse for delayed implementation. Developers are looking for turnover at present. (v) Infrastructure and Planning The developers would welcome a review of planning agreements and in particular what can be expected in the current climate from Section 75 contributions. Planners, like others involved in residential development, are having to tailor their authority’s expectations of developers, of the revenue implications that will flow from planning agreements and the subsequent contribution to infrastructure development. It was hoped that current work around SPP3 and “16/96” would help there to be more consistency in how planning agreements are managed. Some Council officers felt that their prudential borrowing powers could be a useful tool in supporting development as it allowed them to support specified development. Some developers suggested that diversion of resources into infrastructure would be welcome. There was a tacit assumption that the public sector could fund up front infrastructure. There was, however, also recognition of the political nature of funding for large sites hungry for infrastructure. It was suggested that there may be a need to switch policy towards looking at sites in urban areas with existing infrastructure of schools, roads, drainage etc Appendix 1 Programme 10.00-10.30 Registration and Coffee 10.30-10.40 Welcome from Chair Craig McLaren, Scottish Centre for Regeneration, Scottish Government 10:40-10:50 Introduction and context Patrick Flynn, Housing Investment Division, Scottish Government 10.50-11.20 Council Experience of Deferred Receipt Mechanisms Frank Sheridan, Glasgow City Council 11.20-11.40 Coffee 11.40-12.10 Developer Experience of Deferred Receipt Mechanisms Charles Church, Gladedale Ltd Steven Tolson, Ogilvie Ltd 12.10-13.00 Round Table Discussions 13.00-13.45 Lunch 13.45-14.15 Current Legal Aspects of: a) Development Agreements/Licence b) Long Lease Arrangements Paul Warner, Biggart Baillie LLP Alasdair Fleming, Brodies LLP 14.15-14.45 Current Financial and Risks Aspects of a) Development Agreement/Licence b) Long Lease arrangements Liam Fennell, RBS 14.45-15.00 Coffee 15.00-15.50 Panel Discussion and Q&A Featuring all speakers from throughout the day 15.50-16.00 Closing Remarks Allan Lundmark, Homes for Scotland Appendix 2 Public Sector Residential Land Disposal and Development Stirling Management Centre 23 June 2009 Participants List First Name Geraldine Paul Craig Patrick Frank Charles Steve Paul Alasdair Liam Gareth Jim John K Derick Surname McAteer Ballantyne McLaren Flynn Sheridan Church Tolson Warner Fleming Fennell Beaton Low Ferguson Reid Alan Bauer Organisation Scottish Government Scottish Government Scottish Government Scottish Government Glasgow City Council Gladevale Ogilvie Ltd Biggart Baillie Brodies RBS RBS Perth & Kinross Council North Ayshire Council Meridian Residential East Dunbartonshire Council Calum Murray CCG Homes Ltd Andy Wyles Taylor Wimpey Stan Hugh Richard Mike Stephen Jim Mansoor Stuart David David George Mathieson Blake Hughes Duncan Booth Preston Ali Rennie Stewart Metcalfe Adamson NHS Grampian Argyll & Bute Council Tulloch Homes Aberdeen City Council Aberdeen City Council Carronvale Barratt (East Scotland) Lomond Timber Frame Ltd SFHA Clackmannanshire Council Clackmannanshire Council Lucile Stuart Alan Jack Rankin Beveridge Stewart Orr Scottish Government Moray Council East Renfrewshire Council West Lothian Council Steven McLucas Brian Peter Clarke Thomson Moira Alasdair John Douglas Chris Jackie Kirsty Anderson Morrison Dobbie Davidson Burrows McGuire Davidson West Lothian Council Park Lane Development Ltd Miller NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde GVA Grimley Dundee City Council Dundee City Council John Dickie Homes Brodies Brodies Bill Audrey Ian Rhona Miller Greenwood Muir Cameron Alan Colin Tom Jim Brian Ross Connell Axford Kirkwood Skinner City of Edinburgh Council South Ayrshire Council Muir Homes Ltd Scottish Government Redrow Homes (Scotland) Ltd Persimmon Homes Scottish Water Allanvale Land CB Richard Ellis Ltd Sandy Watson Scottish Government _________________________________________________________ _____ Appendix 3 Speaker Biographies. Charles Church, Land Director, Gladedale Ltd Charles is a Chartered Surveyor and Economist with over 25 yrs experience in the property Development Industry having worked across all sectors including commercial and industrial but has concentrated recently on housing and regeneration opportunities. He is currently working with Gladedale , based in Stirling who are one of the largest Private National Housebuilders with offices across the UK. His remit is to secure and negotiate new land and development opportunities in Scotland covering all the major cities including Glasgow, Edin, Aberdeen and Dundee. Liam Fennell, Director Property Ventures, Royal Bank of Scotland Liam Fennell joined RBS Property Ventures in April 2006. Property Ventures has the mandate for equity and mezzanine investment in property projects across the UK. His particular focus is on joint ventures with the public sector . Liam has over 17 years working in economic regeneration projects across Scotland with Scottish Enterprise. He has experience of private public sector partnerships in area regeneration initiatives, commercial property development and specialist science and technology park developments. In addition he has extensive experience in the support and development of industry sectors including biotechnology, life sciences and chemicals. Liam joined the Real Estate Finance in April 2006. Alasdair Fleming, Partner, Brodies LLP Alasdair is a highly regarded commercial property lawyer who heads the firm’s urban regeneration group. Alasdair's reputation and experience as a deal maker, together with his commercial awareness and focus on achieving the best outcome for his clients, has been instrumental in securing his reputation as a leader in the regeneration and commercial property market. With over 20 years' experience in commercial property work, he has been involved in almost every aspect of commercial property, ranging from large scale residential and regeneration projects, to investment and site assembly and disposal. He is admired for developing strong and flexible working relationships with his clients, in both the public and private sectors and is well experienced in developing innovative solutions in ever-changing markets. Allan Lundmark, Director of Planning & Communications, Homes for Scotland Allan joined Homes for Scotland from local government where he dealt, in the main, with economic development and environmental issues. By profession, Allan is a Chartered Town Planner, with extensive project management experience both in the UK and overseas. Allan is responsible for all aspects of planning policy relating to the release of housing land, the design and layout of housing developments and the provision of supporting infrastructure. He also speaks for Homes for Scotland on a range of policy matters and is responsible for developing its communication strategy. Steven Tolson, Director, Ogilvie Ltd Steven is a Chartered Valuation Surveyor and has worked in the development and valuation sectors for some 25 years. He has experience in both the private and public sectors and following his post graduate urban design studies at the University of Strathclyde has developed a niche interest in the value of good urban design. Steven has been engaged in the delivery of a number of master plan projects such as Crown Street Regeneration Project and Craigmillar PARC URC. He also acted as facilitator on the at Homes for the Future, Glasgow City of Architecture and The Drum Housing Project in Bo’Ness. He is now a Director of Ogilvie Group Developments working on mixed use developments throughout Scotland. In addition, Steven has been a visiting lecturer for some 16 years on Urban Design and Planning post-graduate courses at the University of Strathclyde and Edinburgh College of Art and continues to contribute to CPD programmes on urban design and development. He represents RICS Scotland on the Built Environment Forum Scotland and the Scottish Centre for Regeneration Learning Networks and is a member of the RICS Regeneration Forum. Frank Sheridan, Property Development Manager, Glasgow City Council Frank Sheridan is a Chartered Surveyor employed by Glasgow City Council as the Property Development Manager in the Development and Regeneration Services Department. He leads a number of teams with responsibility for Land & Property Development, Valuation, Marketing, Property Information & Mapping. The Land and Property Development Team, was set up to identify, prepare and progress development opportunities, to release additional resources, and to investigate and bring forward opportunities for new and innovative approaches to implementing development, through joint ventures and partnership working. The team is currently at the forefront of developing and implementing development agreements on behalf of the Council and has been responsible for development agreements for Glasgow Harbour, Tradeston, Custom House Quay, the Canal Corridor and the New Neighbourhoods, of Oatlands, Garthamlock & Drumchapel. Paul Warner, Associate, Biggart Baillie LLP Paul joined Biggart Baillie as an associate in the firm's commercial property department in July 2008, having worked previously for Glasgow City Council where he led the in-house commercial property team as Legal Manager for the Council’s Development and Regeneration Services department. In addition to having gained considerable experience in many areas of property work, including disposals, acquisitions, leases and compulsory purchase orders, Paul specialises in multi-faceted, large scale urban regeneration projects. Paul’s previous achievements include acting for Glasgow City Council in the conclusion of a framework agreement governing the £500m Glasgow Harbour project and the conclusion of a development agreement for the regeneration of a 50-acre site in the Oatlands district of the city to yield a development value of approximately £200m. Paul acts for Falkirk Council in connection with the proposed regeneration of Grangemouth Town Centre and generally works closely with colleagues in the Property and Infrastructure, Environment and Transport departments in developing the firm's public sector and projects practices. Appendix 4. Presentations. Please find below a hyperlink to the presentations given on the day. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/BuiltEnvironment/regeneration/pir/learningnetworks/mixedcommunities/recentevent s/PublicSectorLandEvent.