Joel Sherzer: Sketch of the Kuna language

advertisement

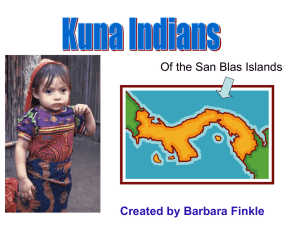

Joel Sherzer: Sketch of the Kuna language (2003) I. Introduction The Kuna Indians are probably best known for their molas, colorful appliqué and reverse-appliqué blouses made and worn by Kuna women and sold all over the world. They are one of the largest indigenous groups in the South American tropics, numbering about 70,000 individuals, the majority of whom inhabit Kuna Yala (formerly known as San Blas), a string of island villages stretching from near the Canal Zone to the PanamaColombia border, quite close to the jungle mainland, where they farm. Living on the edge of modern, urban civilization, the Kuna have managed to maintain their cultural uniqueness through a creative integration of old and new, constantly adapting and manipulating traditional patterns to make them fit new situations. About 24,000 Kuna now live in Panama City, a rapidly growing population. The Kuna language is a member of the Chibchan family, a very broad grouping which extends from the southern end of the Mayan region in Central America into northern South America, that is, from Nicaragua to Colombia. It is not closely related genetically to any other Amerindian language. With regard to social and cultural organization, the Kuna are also unique, remarkably different from the other indigenous populations of Panama and neighboring regions. On the other hand, close and deep analysis of Kuna language, culture, and society, and especially their interaction and intersection, reveals certain similarities with other native groups in Central and South America, including some as far away as Brazil. The Kuna have a rich and dynamic verbal life. Like most tropical forest and lowland South American Indian societies, the Kuna’s world is permeated by and in fact organized 1 by means of their discourse – the mythical chants of chiefs; the histories, legends, and stories of traditional leaders; the magical chants and secret charms of curing specialists; the speeches and reports of personal experience of all men and women; and the greetings, leave-takings, conversations, and joking of everyday life. All of this is oral – spoken, chanted, sung, shouted, and listened to. The Kuna are a fourth world people, a minority in a third world country, and this has implications for their linguistic situation. While one of the most robust of tropical, lowland languages in Latin America, Kuna is nonetheless a minor, minority, local, and oral, and therefore, for all these reasons, an endangered language. While Kuna might be considered to be a vibrant language, in that it has a large number of speakers, and serves as an important, perhaps the most important, identity marker for the Kuna, it must be placed alongside other minority and regional languages, especially in the third world, which are always in danger. In the Kuna case, what is changing and in danger, in addition to the constant possibility of the language just not being used by a new generation, is particular areas of vocabulary, semantic organizations, styles, and discourse forms, genres, processes, and patterns. II. Pronunciation and orthography There are five vowels in Kuna, a, e, i, o, u. These can be pronounced either short or long. The consonant sounds of Kuna are p, b, t, d, k, g, kw, gw, s, ch, m, n, l, r, w, and y. l, m, n, and y can be pronounced either short or long. The voiceless consonants, p, t, k, kw, occur only between vowels in the middle of words. The voiced consonants, b, d, g, gw, when they occur at the beginnings or ends of words, sound at times almost like their 2 voiceless counterparts and in fact in these positions b is pronounced somewhere between p and b, d somewhere between t and d, g somewhere between k and g, and gw somewhere between kw and gw. There is no official Kuna writing system and the language has been written in different ways by different individuals. There are mainly two orthographies in use today, and other orthographies are variants of these two. The main difference between the two is the level of abstraction they represent, especially with regard to intervocalic voiced and voiceless stops. In the more abstract orthography, the distinction between voiced and voiceless stops is represented with single versus double letters. Thus p is voiced; pp, voiceless; t is voiced; tt, voiceless; k is voiced, kk, voiceless; kw is voiced; kkw, voiceless. In the more concrete (and easier for readers to follow) orthography, letters which in Spanish and English are used to represent voiced and voiceless stops are used for Kuna. Thus b is voiced, p, voiceless; d is voiced; t, voiceless; g is voiced; k, voiceless; gw is voiced, kw, voiceless. In both systems the vowels and the sounds l, m, n, and y, when long, are written as double letters: aa, ee, ii, oo, uu, ll, mm, nn, and yy. The two orthographies are easily transferable from one to the other. In ailla, the deposits by Sherzer are transcribed in the more abstract orthography; the deposit by Velarde, in a version of the more concrete one. A complicated issue for the representation of Kuna is the determination of word boundaries. This issue is discussed in the section on grammar below. Here are some examples, which also constitute a glossary for some basic elements and concepts of Kuna life. When the transcription of a Kuna word is the same in the two orthographies discussed here, it is written only once. When the two transcriptions differ, both are provided, with the more abtract one first and the more concrete one second. Notice that k, when followed by a consonant, changes to y (see phonology discussion below). In the various transcriptions of Kuna, this is sometimes represented as y, sometimes as i. Notice also that there is a difference between w (a semivowel) and u (a 3 vowel). Thus wa “smoke;” ua “fish.” Similarly there is a difference between y and i: ye “optative suffix;” ie “forget.” Kuna English nuu dove tii, dii water pookwa, boogwa quiet kae, gae grab, catch sui husband koe, goe deer, baby ua fish waa smoke takke, dake see take, dage come opa oba corn yappa, yapa don’t feel like nate, nade he/she left satte, sate no, none, nothing ome woman, wife mimmi child korokwa, gorogwa yellow, ripe sina pig sinna kingfisher kwalu, gwalu sweet potato kwallu, gwallu oil, light 4 ari iguana asu nose achu dog wisi know wakwa, wagwa grandchild saila chief arkar, argar chief’s spokesman nele seer, shaman suar ipet, suar ibed “owner of stick” (native policeman) ina tulet, ina duled “medicine man” (medicinal specialist) kantule, gandule ritual specialist at girl’s puberty rites sappur, sapur jungle tanikki, daniki is coming warpo, warbo two oblong objects warkwen, wargwen one oblong object ikar, igar path, way soysa he/she said pe, be you neka, nega house neyse to the house tummat, dummad big pane, bane tomorrow kinnit, ginnid red tiwar, diwar river kati, gadi much 5 pinye, binye transform uysa he/she gave kwaysa, gwaysa he/she/it changed okop, ogob coconut wara tobacco wala pole ina medicine inna chicha mola woman’s blouse or cloth panel from blouse ommakket neka, ommaked nega gathering house tule, dule person, Kuna person waka, waga Panamanian merki, mergi North American ulu canoe temar, demar sea tiwar, diwar river purpa, burba spirit kurkin, gurgin hat, brain sunmakke, sunmake speak namakke, namake chant, sing kormakke, gormake shout poe, boe cry, lament totoe, dodoe dance naipe, naybe snake kabur, gabur hot pepper 6 nia devil suar nuchu stick doll karpa, garba basket III. Grammatical structure Kuna is a polysynthetic and agglutinative language, in which many morphemes combine into single words, and in this is typical of and in some ways paradigmatic of native American languages, north and south. The question of what constitutes a word and where word boundaries lie in this as in other unwritten languages is a complicated one. Phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics do not necessarily provide the same definitions of word boundaries. In addition, Kuna seems quite clearly to be undergoing processes of grammaticalization, the development of grammatical forms out of lexical items, a process which we can observe both diachronically and synchronically. With regard to the latter, I would argue that the process of grammaticalization must be central to an adequate description of Kuna grammar. This process is most notably observable in the verbal complex. It also becomes clear when the Kuna language is analyzed in relation to discourse. A. Phonology Typical Kuna morphemes have the structure CV or CVCV, of one or two syllable length. The basic characteristic of Kuna morphemes is that most occur in long or short form, the long form having a final vowel which is deleted in certain linguistic and discourse contexts. When morphemes come together in a single word, as they often do in 7 this polysynthetic language, consonantal changes among neighboring consonants, following the vowel deletion, also occur. The basic rules are as follows: 1. Vowel deletion: the deletion of he final vowel of stems and affixes. 2. consonant deletion rules: when more than two consonants cluster intervocalically, the cluster is reduced to two. a. when a double-stop consonant clusters with another consonant, the double-stop consonant is reduced to a single-stop consonant. b. when more than two consonants cluser intervocalically, all but the last two in the cluster are deleted. 3. consonantal assimilation rules a. l changes to r before another consonant and at the end of a word before a pause. b. k changes to y (pronounced y or i) before another consonant other than k. c. p changes to m before an m. d. t changes to n before an n 4. single and double consonant readjustment rules a. p, t, k, kw are pronounced voiced (as if they were b, d, g, gw). b. pp, tt, kk, kkw are pronounced voiceless (as if they were p, t, k, kw). c. ss is pronounced ch. Notice that the rules move from more abstract representations to more concrete ones (see discussion of orthographies above). Here are two representative examples, with translations in both English and Spanish: (1) pal(i) itto(e)-s(a)-sul(i)-mal(a) 8 again feel-PAST-NEG-PL baritochurmala they didn’t feel anything/no sintieron nada (2) mas(i) itto(e)-na(e)-mal(a)-mo(k(a))-sunn(a)-o(e)-ye taste-go-PL-also-truly-FUT-OPT mas itonamarmosunnoye let’s go taste my food/vamos a probar mi comida Note here and elsewhere that morphemes are often very short, typically one and no more than two syllables, especially after the deletion of the final vowel. B. Morphosyntax With regard to syntax, Kuna is basically an SOV language, though other orders occur, for stylistic purposes. The SOV order is actually both syntactic and morphological, as when pronouns are incorporated morphologically into a single word, by being prefixed to the verb: (3) ome neka takk(e) woman house see ome nega take/ome neydake The woman sees the house/ La mujer ve la casa (4) an(i) pe takk(e) I you see 9 ambedake I see you/yo te veo The personal pronouns, almost clitic like, can be both prefixed and suffixed to various forms. (5) tek(i) an(i) penukk(e)-s(a) well I pay-PAST degan bennus Well I paid/pues pagué Another feature of Kuna morphosyntax worth noting, since it is an aspect of the grammaticalization process, is the existence of a class of preverbs, which modify the verb in various ways. These are often (but not always) words of independent meaning, which take on grammatical meaning in their preverbal context, and have a tendency to be prefixed. (6) sunn(a) “can, be able/puede, ser capaz” an(i) sunn(a) kunn(e) I can eat ansungunne I can eat/ yo puedo comer 10 The order of the preverbal and the pronoun can be switched: sunna an gunne. (7) yer “good, well, bueno, bien” yer kunn(e)-le(k(e)) yer gullege good eat-PAS it tastes good/tiene buen sabor C. Morphology Now to morphology and in particular verbal morphology (see also Llerena Villalobos 1987 and Sherzer 1989). The most characteristic feature of Kuna morphology is suffixation. Most words, especially verbs, which are the core of a Kuna sentence, are formed by adding several suffixes (and a few prefixes) to the stem. The grammatical description of the verb thus involves a statement of each of these suffixes, their meanings, their grouping into classes, their possibilities of order, and their possible cooccurrences. It is useful to group the verbal suffixes into various grammatical/semantic classes. These include tense, which is not well developed, and aspect, which is. Subcategories of aspect are temporal perspective and timing, movement and direction, and position. Other suffixes indicate number, distribution, modality, and passive. Others mark clause linkage and subordination, are narrative markers, or derivational markers. These suffixes tend to be optional, rather than obligatory. They can be viewed as a set of choices that speakers can draw on in discourse. 11 There are certain basic rules of order, selection, and cooccurrence that govern how these suffixes are strung along. In the first position after the verb stem occur suffixes that can also themselves stand alone as verbs. These include one of my primary examples of grammaticalization, the four positionals, which are independent lexical items which can become verbal suffixes. The suffixes of temporal perspective, and many of the movement and directional suffixes also occur in first position, as can the passive suffix leke and the clause connector kala “in order to.” Tense and other temporal perspective suffixes occur in second position, as do some of the movement and direction suffixes. A combination of temporal perspective, modality, number, and distributive suffixes occur in third position. Three of the four clause connectors occur in fourth position. One modality suffix, meaning “possible,” occurs in fifth position. The narrative suffix sunto occurs in sixth position. And the optative, emphatic ye occurs in seventh position. There is a tendency for metacommunicative and line and verse framing words and phrases to become suffixed in final positional also, another case of grammaticalization. Given this general statement of the structure of the Kuna verb, it might be imagined that there are many verbs which contain seven or even more suffixes. But in actual practice, fewer suffixes are used with each verb than would seem theoretically possible. The different styles and genres differ in their utilization of the suffix potential and in fact different constellations of these suffixes are markers of different styles and genres. This situation leads to interesting relations between and among styles and genres with regard to the utilization of suffixes. There are suffixes which have a greater frequency and greater range of meaning in particular styles or genres. In most everyday, colloquial speech, verbs often occur with one, two, or no suffixes. Verbs in magical-curing chanting 12 have at least one and usually two or three suffixes, practically always a positional and the optative suffix ye. The same is true of the chanting of chiefs, which makes use of a different but overlapping subset of suffixes from the magical-curing subset. Narration in formal contexts uses more suffixes per verb than these other styles and genres and exploits the full potential set more widely. Let me now illustrate the situation I have been describing with some representative examples. In addition to illustrating how constellations of suffixes are characteristic of different styles and genres, these examples also illustrate the process of grammaticalization in Kuna, which I will discuss further below. From everyday conversation: (8) ami(e)-s(a) get-PAST amisa Did (you) get (it)?/¿(Lo) encontraste? From magical-curing chanting (9) akku(e)-kwich(i)-ye reach-POS.standing-OPT akuegwichiye Would that (they) be reaching/que estén llegando 13 The interesting suffix -ye has an intersecting set of functions: optative mode, quotative, oral punctuation marker, and poetic line marker. From chief’s chanting (10) noni(kki)-mal(a)-ye come-PL-OPT nonimarye would that we came/que viniéramos From narration within conversation (11) sok(e)-al(i)-sunto say-INCEPTIVE-narrative sokarsundo At that point he said, or: he began to say/en este momento dijo Llerena Villalobos (1987) offers a somewhat different interpretation of -al(i) than the one I present here. He contrasts ali with te, stating that they are both movement suffixes, ali toward the speaker and te away from the speaker. A possible argument for this is that as an independent word ali means “return home,” and its use as a verbal suffix may be a case of grammaticalization. But temporal as well as aspectual (and perhaps discourse) functions and meanings are involved as well, as the following examples from everyday conversation demonstrate. 14 (12) bia be ome dakali “where did you first see (= meet) your wife?/¿Dónde encontraste tu mujer?” (13) gabiali “eyes beginning to close/ojos empezando a cerrarse” (14) gabite “moment in which one begins to sleep/momento en que uno empieza a dormir (se durmió)” (15) gabisa “already slept/ya durmió” Another interpretation of these contrasting meanings, suggested by Villalobos, is that they are metaphorical, i.e., that the suffixes, while grammaticalized, can also be used metaphorically. In particular, when movement suffixes are used with verbs involving mental or intellectual activities, they seem to result in a metaphorical meaning. Thus contrast: (16) madun gunnadapi “he is going along eating a banana/está caminando comiendo un guineo” (17) dule gaya durdaynadapi “he is learning Kuna/está en proceso de aprender el idioma Kuna (literally: going along learning) in which the suffix -natappi “going along” is used metaphorically (see Llerena Villalobos: 29, 31-32). From formal narration of a personal experience 15 (18) an(i) panku(e)-s(a)-mal(a)-mo(k(a))-ye I leave-PAST-PLURAL-also-OPT ambangusmarmoye/an bangusmarmoye I left you/les dejé From formal narration of a traditional folktale (19) amie(e)-al(i)-ku(a) look for-INCEPTIVE-when amiargua when he began to look for (it)/cuando empezó a buscarlo To summarize: What I have described here is a situation in which grammar, style, and discourse overlap and intersect. It is very hard and probably not appropriate to separate them. D. Grammaticalization Within the verbal complex I have just described, there are several classes with regard to grammaticalization. 1. There are suffixes which are purely grammatical and have no synchronic lexical equivalents, i.e., the process of grammaticalization is not evident. These include tense markers, some, but not all temporal perspective aspectual markers, the passive voice 16 marker, the distributive marker pali, some but not all movement and direction markers, and modals, except suli “no.” Note that the causative prefix o- is also in this class in that it has no lexical equivalent. 2. The distributive suffix moka “also” and the plural suffix mala can occur with both verbs and nouns, as can the benefactive suffix kal(a), which has slightly different meanings with nouns and verbs. None of these have lexical equivalents that can stand alone. 3. The personal pronouns, especially an(i) “I” and pe “you,” which are prefixed, and many positional, directional, and movement suffixes all have lexical equivalents and are quite obviously derived from them. Examples are kwichi “in a standing position,” natappi “going along,” nae “go,” tani “come,” and noni “came.” 4. An interesting class I have not discussed involves a set of line and verse and turn at talk framing words and phrases, akin to discourse markers. Some of these can be suffixed to verbs and grammaticalized. (20) an(i) pe attursa(e)-ma(i)-ma(i) takken I you rob-POS.lying-POS.lying see ambeatursamamadaken we are robbing you see/les estamos robando ve. (21) kaa sunmakk(e) soke pepper speak say kaa sunmaysoge 17 The pepper speaks it is said/El ají habla se dice E. Positional suffixes A very good example of the Kuna grammaticalization process is the set of positional suffixes, which when suffixed can lose their positional meaning and take on other, grammatical meanings. When they are verbal suffixes, their primary meanings are existence and ongoing state, though the positional meaning can emerge and even be marked. (22) yartakk(e)-na(i) trick-POS.perched yardaynai they go about tricking one another/andan engañándose (23) panama-ki(ne) arpa(e)-mai panama-in work-POS.lying banamagi arbamai he is working in Panama/está trabajando en Panamá (24) mas(i) kunn(e)-si(i) food eat-POS.sitting masgunsi he is sitting eating/está comiendo sentado 18 (25) sunmakk(e)-kwich(i) speak-POS.standing sunmakwichi he is standing speaking/está hablando parado 4. Semantics Since my goal here is to provide a general typology of the Kuna language, I want to say a few words about semantics. I begin with a particular feature which Kuna shares with a number of American Indian languages, including some Chibchan languages and most Mayan languages, neighbors to the north, form/shape numeral classifiers (Sherzer 1978). These are part of a general semantic/grammatical attention in Kuna to form and shape, as well as position, movement, and direction. Here are some examples. (26) es ka-kwen “one (slender) machete/un machete (delgado)” (27) aswe kwa-kwen “one (round) avocado/un aguacate (redondo)” (28) tule war-kwen “one (oblong) person/una persona (oblonga)” Grammaticalization seems to be involved with at least some of these, for example, wala “oblong, pole-shaped,” which is quite obviously derived from the noun wala “tree, pole.” Another aspect of semantics is lexicon. The Kuna lexicon reflects its close relation to the dense tropical and maritime ecology of San Blas, with literally hundreds of words for 19 different types of fish, plants, and birds. Also focused on ecology is the fascinating vocabulary of reduplicated adjectives, which is used to describe the textures of plants and trees. Plants and trees are organized in terms of underlying semantic systems, which involve political economy, curing practices, and ownership. 5. Discourse I turn now to a final focus on discourse. Kuna discourse, especially traditional, is remarkable for its diversity. This includes much chanting -- of legends, myths, and personal experiences by chiefs, of curing and magical chants by medicinal specialists, of puberty chants by puberty specialists, of playful narratives by their knowers and of lullabies. Traditional and personal narratives can be either chanted or spoken. Speeches of all kinds are common. These include reports and political rhetoric. In addition to these forms and genres of discourse, there are also patterns and processes. These include grammatical and semantic parallelism, constant quotation of direct discourse, considerable metacommunication, line and verse framing words and phrases, and dialogic performances. (For Kuna discourse, see Sherzer 1983, 1990.) 20 References Llerena Villalobos, Rito (1987): Relación y determinación en el predicado de la lengua Kuna. Bogotá, Colombia: Centro de publicaciones de la Universidad de los Andes. Sherzer, Joel (1978): Cuna numeral classifiers, in M. A. Jazayery, E. C. Polomé, and W. Winter (eds.), Linguistic and literary studies in honor of Archibald A. Hill. The Hague: Mouton, Volume 2, 331-337. Sherzer, Joel (1983): Kuna ways of speaking: An ethnographic perspective. Austin: University of Texas press. Sherzer, Joel (1989): The Kuna verb: A study in the interplay of grammar, discourse, and style, in: Mary Ritchie Key and Henry Hoenigswald (eds.), General and Amerindian Ethnolinguistics: In Remembrance of Stanley Newman . Berlin: Mouton, 261-272. Sherzer, Joel (1990): Verbal art in San Blas: Kuna culture through its discourse. Austin: University of Texas press. (This document also appears in Professor Sherzer´s web project www.ailla.org. We thank him for allowing us to feature it here). 21