LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE - The University of Sydney

advertisement

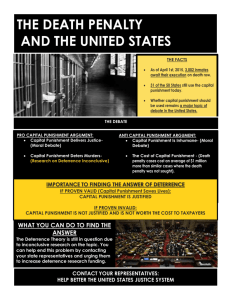

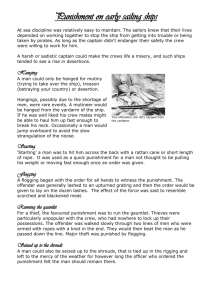

LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY JURISPRUDENCE LECTURE OUTLINE ALL STUDENTS PLEASE NOTE: The outline below is intended to assist students in following the lectures in the course and in understanding the recommended reading. The outline is not a substitute for the lectures and reading. The outline is not intended to be comprehensive. Students who have merely familiarised themselves with the outline but not attended the lectures and read the prescribed text and readings will be inadequately prepared for the exam and at substantial risk of failure. Examination questions will increasingly ask students to apply the concepts and arguments taught in the course to an issue or problem. Students will be best prepared to deal with the paper who have attended the lectures or weekend schools and read widely. Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 1 LECTURE 11 CRIME AND PUNISHMENT Introduction Philosophy has provided a number of important theories about the nature of our responsibility for criminal conduct and the justification of punishment. These two issues are related. The nature and amount of punishment we consider appropriate for a crime is closely related to the reasons we believe people should be held responsible. Why do we punish people? Anglo-American jurisprudence usually distinguishes between the mens rea or criminal intent of an offender, and the actus reus, the criminal act. The necessity for each element to be present in regard to most crimes reflects the underlying doctrine of the criminal law that people are not punished merely for wicked intentions if those intentions have not been acted upon, nor for causing harm where it occurred through accident or in the absence of a blameworthy mental state. The usual mens rea for a criminal offence is that the criminal has intended the consequences which occurred, or acted with reckless indifference to whether such consequences were caused. The problem of moral luck and free will The doctrine of mens rea in the criminal law reflects a belief about the nature of human conduct. Most of us believe that we choose to engage in our intentional conduct, that we could have chosen otherwise, and that this process of choice involves some form of mental act. Only being responsible for those actions that we have intentionally chosen ensures that we have some control over life. Imagine being criminal liable for anything that you caused, even accidentally. Further, whether the punishment is based upon deterrence or upon retribution, it seems to make more sense to punish people where they have chosen to do wrong rather than in instances where they have caused harm but could not have avoided it. Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 2 Many have argued that our system of criminal law thereby assumes that we have a free will. Although some philosophers have accepted that we are able to alter our future through completely unconstrained mental choices, science appears to present us with a picture of the universe determined by physical law and without room for the existence of a notion of free will. In suggesting that the punishment should be proportionate to the crime we usually intend that what makes crimes of greater or lesser significance is the extent of the offender’s wickedness, governed by the extent of the intended harm. The principles just referred to create a paradox for the criminal law. It appears hard to justify different punishments because of different consequences where the different consequences were purely the result of luck. (eg, The NSW Crimes Act provides for a penalty of up to 10 years for causing death or serious injury driving under the influence of liquor or a drug or at speed or in a manner dangerous. By contrast, traffic legislation provides for a summary offence of driving in a manner dangerous with a much lesser penalty. However whether one causes death or serious injury while driving in a manner dangerous will usually have little to do with the intention of the offender). Nagel and Williams in essays both entitled “Moral Luck” have argued that we can never eliminate entirely an element of luck in the way in which we apportion moral or criminal responsibility. The justifications of punishment It has frequently been asserted that punishment is justified by one or a combination of the following reasons: Rehabilitation Deterrence Retribution Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 3 Rehabilitation The rehabilitative model represents criminal conduct as a symptom of a psychological condition from which the offender should be cured. If it be possible to rehabilitate people while they are being punished for other reasons there seems good ground for attempting rehabilitation. Difficulties may arise where the demands of effective rehabilitation conflict with effective punishment justified on deterrence or retributive grounds. Deterrence Deterrence justifications treat punishment as a means to an end. Contemporary deterrence theories are often traced back to Bentham’s utilitarian moral philosophy. Bentham also wrote on criminological and penological theory. The utilitarian calculus treats any form of human suffering as a cost requiring justification through the production of a greater and countervailing measure of human happiness. From this perspective punishment of offenders will only be justified if the punishment will have the effect of deterring the offender and other potential offenders from future criminal acts that would, if committed have caused suffering in excess of the offender’s suffering from being punished. Leaving aside the practical difficulties of measuring the gains and losses, deterrence theories raise a number of other issues. Firstly, it treats the punishment of the offender not as something the offender deserves for his wrong but as a means to the achievement of some other desirable social end. Some argue that it devalues individual autonomy in treating people as means rather than ends. It does not appear necessary from the viewpoint of the utilitarian calculus that a person actually be guilty. If sufficiently many people believe the person punished was guilty and Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 4 are deterred by the example of that punishment, the punishment may be an effective deterrent even if the prisoner be innocent. Many utilitarians argue that if we did not strive to avoid punishing the innocent there would be further suffering caused through the anxiety of the general population, fearful that they might be the next victim of an undeserved episode of punishment. This might be a practical reason why we would not usually punish innocent people, but it appears to be a deficiency in the theory that it says that there is nothing in principal wrong with punishing innocent people. It also follows from the deterrence theory that the punishment need not be proportionate to the crime. The deterrence theory treats the suffering of the offender in being punished, and the suffering of the victim, as of equal moral significance. There are certain offences which appear undeterrable, deterrence theory would therefore suggest we do not punish at all. Braithwaite and Pettit argue for a modified theory of deterrence. They suggest that the error of early deterrence theories was to advocate the maximisation of human happiness or welfare. They suggest that punishment seeks to maximise the value of personal dominion. This value reflects our autonomy and ability to control our own lives. If we punish in a fashion which will seek to increase the importance of this value in society then we will not punish innocent people and our punishment may also reflect in some fashion the proportionality principle but we will also have the flexibility to adjust punishments to reflect rehabilitative and deterrence aims. Why however, should we maximise only this value? Retributive theories of punishment Retributive theories have had a renewed popularity in criminological theory in the last thirty odd years. Herbert Morris’ article “Persons and Punishment” (see course materials) was one of the first examples of the new retributivism. Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 5 Morris’ argument is firmly based on the principle of justice that a criminal deserves punishment, because, having enjoyed the benefits of living in society, criminal conduct reflects an attempt to evade the burden of obedience. Punishing the offender deprives him or her of the unmerited advantage which he or she would otherwise gain and hence restores a just equilibrium with all other members of society in bearing the benefits and burdens of social life. It is sometime objected to arguments akin to that of Morris’ that it assumes the offender gained some benefit from their criminal conduct. This may seem improbable if it was a spontaneous outburst of uncontrolled violence. Sadurski in “Giving Desert Its Due” points out that it is not the benefit gained by the criminal in breaking the law which merits punishment, but rather, the criminal’s rejection or refusal to accept the restraints imposed by law on the conduct of us all, which brings into play the principle of punishment. Finnis also puts forward a retributive theory arguing that in breaking the law the criminal has arrogated to him or herself a freedom of choice or liberty in action to which he or she is not entitled. Punishment restores the balance or equilibrium by depriving the offender of that liberty. The advantage of retributive arguments In suggesting that the justification of punishment lies in restoring some sort of equilibrium between the obligations or burdens borne by the law abiding on the one hand, and the offender on the other, retributivism can explain why we punish only the guilty and never the innocent, since only the guilty have gained the unmerited advantage which calls for punishment. Likewise, retributivism can explain the principle of proportionality. The graver the offence the greater the burden of obligation or control the offender has repudiated and the greater the punishment called for. Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 6 It is also said in support of the retributive justification of punishment that it treats people as ends rather than means. It explains why offenders deserve their punishment and why we should punish them regardless of the social benefit that might otherwise flow. Criticisms of the retributive viewpoint The concept of proportionality while explicable in theory is hard to give effect to in practice. How do I decide how much more punishment an armed robber deserves then someone who commits a common assault? The proportions awarded by the criminal law appear to be determined more by historical and cultural factors then by some scale of objective moral dessert. Strong retributivists argue that there should be no clemency or discounts. Indeed, it will be unjust on this view to punish an offender any less than the amount that he or she deserves. The retributive viewpoint may be difficult to reconcile with rehabilitative aims. Mixed theories HLA Hart in his work “Punishment and Responsibility” argued that we appeal to utilitarian and deterrence type arguments in justifying the existence of a law or general rule. Thus, the law against dangerous driving exists because of the general social good produced by having a norm discouraging dangerous driving. On the other hand, Hart considered that in punishing individual offenders one had to give recognition to a principle of justice which required that they not be punished beyond the amount that would be proportionate to the offence. Most sentencing judges argue that they take into account deterrence, retributive and rehabilitative goals in arriving at the correct sentence. Some might argue that some values may be pre-eminent over others. Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 7 Are we permitted to punish people more than they deserve for deterrence reasons? Perhaps however we should discount punishment to reward informers. The correctness of appealing to multiple value justifications of punishment depends upon one’s general views about moral justification, and whether one accepts that there are a plurality of moral values which need reconciliation, or whether there is a pre-eminent moral value which will usually dictate the outcome in a case. Usual sentencing practices reflect the plural approach. Teleological theories of punishment Some philosophers (eg, Robert Nozick and Joel Feinberg) have argued that punishment is justified as an expression of society’s values, and aims to bring the offender to the point of recognising those values. On some of these theories it is important that the offender achieve a state of repentance. It does seem important in the process of punishment that people know and acknowledge why they are being punished. On the other hand, teleological justifications appear insufficient as complete justifications. How can I justify continuing to punish someone who has fully repented and fully accepted society’s values? Punishment, time and personal identity A further major issue in the justification of punishment is the impact upon an offender’s moral or legal responsibilities of the passage of time. Are we right to treat a person as a single indivisible entity that persists throughout time? Does an offender deserve to be punished just the same amount if caught 20 years after the offence, as when punished straight after the offence? Derrick Parfit argued for a reductive theory of personal identity. In this theory we are in a sense not a single indivisible entity throughout our lives but a series of phases, albeit closely Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 8 connected ones. The term ‘person’ describes that bundle of phases, usually associated with a specific body (but not perhaps in the future if we master brain transplants – or perhaps better described as body transplants). Parfit argues that in a real sense we are not the same person now as we were 20 or 30 years ago. We have different memories, different values, different thoughts. This may affect the extent to which we deserve to be punished for something we did long ago in our past. Does memory loss affect our liability for punishment? What if after having committed a crime I suffer a brain accident and lose the whole of my autobiographical memory regarding my life at the time of the offence. Do I still deserve to be punished even though I have no internal recollection or knowledge of having committed the crime, or how or why I did it? Dr C Birch (LEC Winter 2006 Session) 9