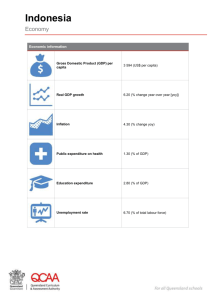

Trade, aid and development in Indonesia

advertisement