RS Origins of Writing

advertisement

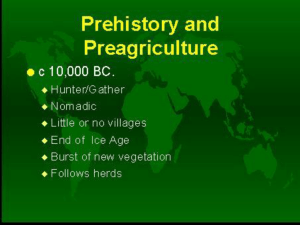

Anthropology 5 -- Ancient Civilizations Review Sheet #2: Writing Systems and Counting Systems Counting systems: The first evidence of a numerical system (i.e., orderly and accurate counting) is evident in the Upper Paleolithic (i.e., c. 35,000 – 15,000 B. P.). As trade became more complex and extensive, a numerical system of accounting for the goods traded was needed. The Sumerians had a base-60 counting system, we still use it for counting time; today we have a base-10 decimal system. The Romans used numbers made up of strings of letters, i.e., Roman Numeral. Modern numerals and the base10 system originated in India c. A.D. 500. Writing system: Writing created an information revolution, allowing for the first time one generation to pass on its accumulated knowledge in permanent form to succeeding generations. There are four primary writing systems: 1) pictographic writing For example, the hieroglyphic systems of the Egyptians or Mayans, in which a given picture or sign stands for a particular word or idea (e.g., a picture of a fish means fish). There are two problems with pictographs: 1) many symbols are needed and 2) abstract concepts cannot be easily expressed. 2) syllabic writing For example, the cuneiform (Latin for wedge-shaped) system of the Sumerians and most of the ancient Near East, in which words and ideas are spelled out phonetically, syllable by syllable. The characters consist of arrangements of wedgelike strokes, generally on clay tablets. The Babylonian and Assyrian writing system used 700 arbitrary cuneiform symbols for words and syllables, some originally pictographic. Cuneiform writing was used to express political, juridical, literary, philosophical, and religious ideas. Cuneiform writing was used outside of Mesopotamia, but was not common after the Persian conquest of Babylon (c. 539 B.C.E.). In use for almost 3000 years until Aramaic, an alphabetic writing system replaced it in the Near East. NOTE that hieroglyphic writing is not entirely pictographic, nor is cuneiform wholly syllabic. 3) ideograph writing A refinement of pictographic writing. Here a symbol conveys an idea, but the symbol does not necessarily resemble the idea being conveyed. For example, in the Aztec writing system a “feather” represented the number 400. Since the association between an ideograph’s structure and meaning is highly arbitrary, one can create ideographs for any concepts one might wish to express in speech. The problem with ideographic writing systems like Chinese is that to read a newspaper requires knowledge of about 3000 symbols (there are 4500 symbols in Chinese writing). 4) alphabetic writing in which phonetic symbols represents a particular sound. This is the most efficient system because the number of basic sounds in any language is very limited; no language has more than about 50 sounds. For example, English uses only 26 symbols to form an alphabet. Alphabetic symbols for phonemes are combined to make syllables and then words. The Phoenicians were the first to developed an alphabetic writing system c. 3300 B.P.. It spread around the Mediterranean Sea, in particular, to the Etruscans and then to the Romans and eventually to us. These systems are much more efficient that earlier systems. The Phoenician L and Q are same as ours; Hebrew script stems from the Phoenician writing system. Two innovations in the recording system occurred c. 5400 B.P. as urbanization occurs and trade becomes more extensive and diverse: 1) clay tokens The first evidence of written system is c. 10,500 B.P. in Mesopotamia. A newly developing agricultural economy required a recording system. Archaeologists first thought that clay tokens were gaming pieces, but because they were fire-harden for permanence some scholars wonder. Clay tokens are small, i.e., less than an inch in size; imprinted with shapes that include: spheres, rods, discs, and cones; each representing a different item or commodity. Some of the geometric forms were symbolic, e.g., they were a unit of a particular commodity like a basket of grain. They become more complex, e.g., with parallel lines and dots, and eventually the system expands to 250 different shapes as new commodities, both local and imported, appear. Some have perforations so that they could be strung together as records of transactions during transportation between the urban areas. This system of recording remained stable and in use from c. 10,000 B.P. to 4000 B.P.. They are very abundant and widespread in the archaeological record of the Near East; indicating their popularity and extensive use in ancient times. 2) bullae These are clay balls which were used as envelopes to hold the clay tokens, are about the size of softballs. They are sealed to prevent tampering with contents. They were often impressed with a cylinder sealed representing the owner. The drawback was that they concealed the contents and had to be destroyed to verify the transaction. To overcome this problem, people began to impress the wet surface of the bullae with the number and rough shape of the tokens within. Note: this is the critical link between the three-dimensional tokens and the two-dimensional writing system. Now anyone familiar with the token system could read the clay balls and understand the details of the transaction. A marginal innovation, the bullae actually transformed an accounting method into writing system. clay tablets Eventually, the bullae and tokens were replaced by a flattened piece of clay. On these the numerical signs and images were impressed. Token impressions were quickly replace by incised markings which were more precise and easier to read. Clay tablets with economic information on them first appear c. 5400 B.P. in Uruk. The script is written with different shaped styli made from reeds. Scribes were important craft specialists in the urbanization process. It took years to learn the 600 or more characters used in cuneiform or hieroglyphic writing. H. W. Schulz, City College of San Francisco 09/26/07