Limno course outline 95 - Kennesaw State University College of

advertisement

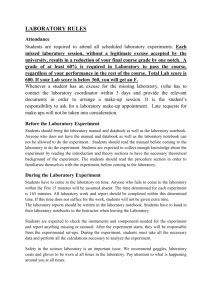

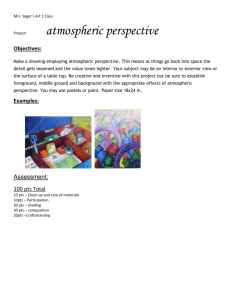

INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY BIOLOGY 3310 SPRING 2016 Dr. Dirnberger (770) 423-6546 338 Science Building jdirnber@kennesaw.edu http://science.kennesaw.edu/~jdirnber/InvertZoo "Indeed, invertebrate zoology was not a term that then existed (since Lamarck was to be the first to distinguish vertebrates from invertebrates). What he [Lamarck] was occupying was the chair of all the zoology that nobody wanted. Birds, mammals, reptiles, fishes…-- there were men eager to profess them all. What was left over -- in God’s good creation and the dusty museum drawers -– was a lot of vermin in the way of snails, squids, spiders, insects, scorpions, worms, and such ‘coquillage’ as oysters, lobsters, shrimps and the like. This protean rubbish had baffled Linnaeus and all the other systematizers, and it had neither been classified nor seriously examined…In short, it was in limbo –- the midden of God’s lowlier efforts. And it was nineteen-twentieths of the animal kingdom." -- A description of invertebrate zoology as it existed when the naturalist Jean Baptiste Lamarck was appointed its chair following the French Revolution: Donald Culross Peattie, Green Laurels: The Lives and Achievements of the Great Naturalists. Simon and Shuster, Inc., New York, 1936. "He seems to have an inordinate fondness for beetles." -- Repy by the famous British Biologist JBS Haldane (1892-1964) referring to the more than 250,000 described species of beetles when asked whether his life-long studies had taught him anything about the creator of the universe. LECTURE COURSE DESCRIPTION Unlike most other biology courses (which are based on specific sub-disciplines of biology), invertebrate zoology is a broad view across the fields of ecology, physiology, cell biology, embryology, behavior, evolutionary biology and others. The tremendous diversity in form and function of the invertebrates provides unique and important insights into these fields. This course is a journey into a world often overlooked, a world of the bizarre and the under-appreciated. There is an old Chinese curse that goes “may you live in interesting times”. These are interesting times for the field of Invertebrate Zoology. Most of the described species on Earth are invertebrates (~1 million invert species), and yet after two centuries of study we have failed to find a satisfying solution to the basic evolutionary relationships of the major invertebrate phyla. However, with the recent use of molecular sequence data, developmental genetics and new fossil discoveries, many zoologists feel that the puzzle pieces are finally falling into place. In addition to studying the phyla themselves, we will examine many of the controversies that surround this debate on their relationships to one another. COURSE OBJECTIVES Distinguish phyla and other taxonomic subdivisions of invertebrates based on unique sets of characteristics possessed by each group, and recognize the diversity in structure, function and natural history across the broad survey of biodiversity covered in this course. Argue phylogenetic relationships among major taxa based on characteristics of organisms surveyed in this course, and recognize difficulties inherent in using various types of evidence to construct such relationships. Describe the general pattern of phylogenetic relationships most currently accepted and contrast this to past ideas on the relationship of major invertebrate phyla. Generalize patterns and processes of macroevolution and ecology based on the broad survey of biodiversity covered in this course. Recognize the ecological, economic and medical importance of various invertebrate taxa. Demonstrate the ability to locate, sample and identify common taxa of invertebrates found in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial environments of Georgia. Relate structures observed in lab to the environment from which organisms were collected by applying evolutionary concepts. REQUIRED BOOKS Pechenik, Jan A. Biology of the Invertebrates, McGraw-Hill, NY. No lab manual for lab except for a blank bound notebook. CLASS WEB PAGE http://science.kennesaw.edu/~jdirnber/InvertZoo This will link you to lecture outlines and to other resources. While these outlines are detailed, they are not complete lecture notes (i.e. this is not an online course). EXAM DATES Mini-Exam on basic phylogeny: 29 January Exam I: 29 February Exam II: 15 April Exam III: 4 May, 8:00 am Mini-Research Paper, 14 March COURSE OUTLINE FOR INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY LECTURE I. Introductory Lectures – A basic phylogeny of the invertebrates and some basic terminology II. The parade of phyla! Each has its own story. MINI-RESEARCH PAPER This paper will address a question of your choosing from the “Topics for Further Discussion and Investigation” found at the end of every chapter in your textbook. You must choose a topic that has three or more sources cited below it. Read and use these scientific papers to answer your question. Paper format 1, State the question you choose to answer. 2. For each of the three journal articles you are using to answer the topic you have chosen, write a paragraph in your own words that summarizes that paper (do not use quotes). Cite these sources within the body of your summary; e.g. “(Smith, 2001)”, or “according to Smith (2001)…”. 3. Include a final paragraph with some original thought in which you draw some overall conclusions concerning these three papers. Do all three papers reach similar conclusions (if so, which paper presented the most convincing argument and why; if not, why did their conclusions differ)? What do these three paper collectively indicate still needs to be studied? 4. Provide a “Literature Cited” section listing the three papers you discussed. You must find and read (either in the KSU library, through inter-library loan, or online) at least three of the journal articles listed below your topic. Use (and cite) these journal articles to answer the question/topic in your paper. Your paper should be about 2-3 pages long. You may be able to get one or more of the articles on-line. For example, the KSU library gives us access to JSTOR (Journal Storage: The Scholarly Journal Archive). Go to: http://www.jstor.org/ if you are on-campus. The library may have these articles in there holdings. To see which journals the KSU library has, go to: http://dewey.kennesaw.edu/cf/jrnlsfrm.htm If you cannot get the article online or at the KSU library, you must go through interlibrary loan. This can be done online using an electronic form at: http://kennesaw.illiad.oclc.org/illiad/logon.html. It sometimes takes a week or two to get the article so plan to find your articles well before the due date. Do this only if you have confirmed that the library does not have this journal; they will not provide the article if the journal is at KSU. Due Date: 14 March – Turn in your paper electronically through Turnitin.com (you must “enroll” at this site: the class id is 11293216 and the password is “InvertZoo”) LAB We sat on a crate of oranges and thought what good men [people] most biologists are, the tenors of the scientific world-temperamental, moody, … loud-laughing, and healthy. Once in a while one comes on the other kind -- what used in the university to be called a "dry-ball" but such men are not really biologists. They are the embalmers of the field, the picklers who see only the preserved form of life without any of its principle. Out of their own crusted minds they create a world wrinkled with formaldehyde. The true biologist deals with life, with teeming boisterous life, and learns something from it, learns that the first rule of life is living. The dry-balls cannot possibly learn a thing every starfish knows in the core of his soul and in the vesicles between his rays. He must, so know the starfish and the student biologist who sits at the feet of living things, proliferate in all directions. Having certain tendencies, he must move along their lines to the limit of their potentialities. And we have known biologists who did proliferate in all directions: one or two have had a little trouble about it. Your true biologist will sing you a song as loud and off-key as will a blacksmith, for he knows that morals are too often diagnostic of prostatitis and stomach ulcers. Sometimes he may proliferate a little too much in all directions, but he is as easy to kill as any other organism, and meanwhile he is very good company. - John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts from The Sea Of Cortez, reflections on their collecting voyage along the Gulf of California LAB OBJECTIVES Invertebrate zoology labs typically focus on examination and dissections of standard specimens (the ‘usual suspects’ like the earthworm). However, labs in this course will focus on field collection and laboratory identification of invertebrates that inhabit our region. We will focus on collections, identification, and study of invertebrates in this region. By taking this approach, you will not only become familiar with basic invertebrate anatomy and diversity, but also gain an awareness of a major part of the biodiversity that surrounds us. LAB OUTLINE FOR INVERTEBRATE ZOOLOGY Topic No lab Intro to notebooks /Intro to illustration/ Intro to keys Pond sampling (plankton)* and work-up Stream sampling* Freshwater work-up Pond sampling (benthos)* and work-up Marine fauna work-up (live specimens) February 24 and FW Quiz March 2 Marine fauna work-up (arthropods) March 9 Marine fauna work-up (other macrobenthos) March 16 Marine fauna work-up (plankton and finish up other) March 23 Terrestrial sampling* (cryptozoa) and Marine Quiz March 30 Terrestrial sampling* (macro-inverts) No lab: Spring Break April 6 April 13 Terrestrial sampling* (macro-inverts & habitats) April 20 Terrestrial Quiz and Journal due April 27 No lab * field trips – dress accordingly; come to lab even if the weather is bad January 13 January 20 January 27 February 3 February 10 February 17 EXPLANATION OF THE LABS After some introductory activities and discussions, the lab proportion of this course will be divided into three main sections covered sequentially over the semester: freshwater, marine, and terrestrial. We will collect invertebrates from their native environments, and identify and describe collected specimens in lab. Your effort in lab will be assessed in two ways: Natural History Journal: You will be required to develop journals of your field and lab experiences. This will not only give you something more permanent to carry away from this course, but also help you develop a broader understanding of the natural history of the invertebrates, as well as refine your powers of observation. A notebook done well will help you as you study for your laboratory mini-practicals. I hope that you will produce something you will be proud of and can use in the future to find and recognize critters in this region. This journal should be neat and organized. The notebook itself should be sturdy, bound, and hard-covered; it maybe lined or un-lined depending on your preference. Notebooks are sold at most bookstores and art supply stores. Spiral bound notebooks are not allowed. Bring your journal notebook to every lab. During the semester, I will check your progress (for credit) and make suggestions for improvement. The journal will be turned in near the end of the semester (see lab schedule on previous page). There will be a 5% deduction per 24 hours after the due date! Criteria used in grading notebooks: Completeness, neatness, organization, accuracy, and clarity Observation ability Synthesis of observations and thoughts A detailed handout on requirements and suggestions for your journals is available on the lab webpage for this class. The final entry in your journal should be a “Final Synthesis Section” that will include a few pages comparing and contrasting adaptations of invertebrates from the different environments that we collected from. Describe any general trends in morphology, behavior, lifestyle, dispersal stages, general size, etc. among environments. Be sure to include a discussion of how these environments differ and relate this to specific adaptations that you have observed. See the handout on the Invert Zoo Lab Webpage for some ideas. Be sure to cite some specific examples from your previous journal entries to back up your conclusions! Lab quiz/mini practicals: I will post a list of the most common organisms on the lab webpage prior to the “lab quiz/mini practical”. The “lab quiz/mini practical” will consist of identifying some of these taxa from some combination of descriptions, illustrations and actual specimens. The best study guide for these mini practicals are your journals, so make sure you make good, detailed notes of specimens in your journals. OFFICIAL STUFF FOR BOTH LECTURE AND LAB: GRADING LETURE POINTS Mini-Exam on basic phylogeny Exam I: Wednesday Exam II: Wednesday Exam III Wednesday Mini-Research Paper 50 pts 100 pts 100 pts 100 pts 25 pts (375 pts) LAB POINTS Journal (lab notebook) 3 Lab Quizzes/Mini-practicals @ 30 points each 5 notebook checks at the end of some labs @ 4 points each 50 pts 90 pts 20 pts (160 pts) Participation / group work points Total points for determination of final course grade: 15 pts 550 pts A= >90%; B= >80%; C= >70%; D= >60% OFFICE HOURS MONDAY, WEDNESDAY 1:30-3:30 PM; TUESDAY 9 AM – 12 PM If you cannot make it during these times, I will be glad to make an appointment with you. If you are having any problems with the material, please come by and see me. Don't put it off until it is too late! PREREQUISITES Biology 2107, 2108 POLICIES You must show up for field trips on time or you will get left behind! Attendance for both fieldtrips and lab are important; the quality of the material in your notebook will suffer considerably if you miss both fieldtrips and ID labs! Keep all of your returned, graded work. You must have these materials if you decide to contest your final course grade. To find out about school closings due to inclement weather, check the KSU website: http://www.kennesaw.edu. Late assignments will result in a 5% reduction per 24 hours. For excused absences, provide documentation as soon as possible. Do not request grade info by email. I am not allowed to send grades by email. LAB SAFETY Safety must be a primary concern when in lab and in the field. You must review the Laboratory Safety Guidelines at: http://science.kennesaw.edu/biophys/LabSafetyGuideNoPi c.doc. When we are in the field, watch where you step. Don’t reach into an area that you cannot see into. Wear shoes that cover the foot and socks that cover the ankle to avoid poison ivy and bites. Avoid contact with wildlife and even with domesticated animals including dogs and cats. If the weather is hot and sunny, be sure to stay hydrated. Avoid fast moving water and deep areas, especially while wearing waders. Let me know before going into the field whether you are allergic to such things as bee stings. ACCOMMODATIONS Any student with a documented disability or medical condition needing academic accommodations of class-related activities or schedules must contact the instructor immediately. Written verification from the KSU disAbled Student Support Services is required. No requirements exist that accommodations be made prior to completion of this approved University documentation. All discussions will remain confidential. ACADEMIC WITHDRAWAL The policy for academic withdrawal can be found at http://catalog.kennesaw.edu/content.php?catoid=24&navoid=2171#withdrawalfromclasses LAST DATE TO WITHDRAW WITHOUT ACADEMIC PENALTY is 2 March 2016 ACADEMIC INTEGRITY Every KSU student is responsible for upholding the provisions of the Student code of Conduct, as published in the Undergraduate and Graduate catalogs. Section II of the Student Code of Conduct addresses the University’s policy on academic honesty, including provisions regarding plagiarism and cheating, unauthorized access to University materials, misrepresentation/falsification of University records or academic malicious/intentional misuses of computer facilities and/or services, and misuse of student identification cards. Incidents of alleged academic misconduct will be handled through the established procedures of the University Judiciary Program, which includes either an “Informal” resolution by a faculty member, resulting in a grade adjustment, or a formal hearing procedure, which may subject a student to the Code of Conduct’s minimum one semester suspension requirement.