Martha Ann Allen - Wake Forest University

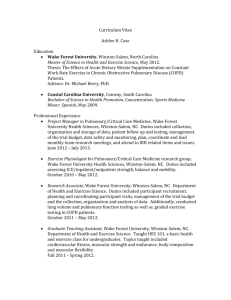

advertisement

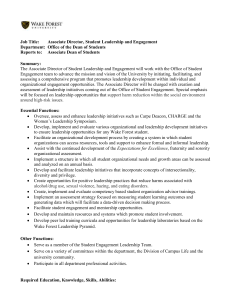

A Historical Look at the Story and Significance of Martha Ann (Allen) Turnage: The First Female Debater at Wake Forest College Rebecca R. Eaton History of Wake Forest Dr. Ed Hendricks May 8, 2003 Since the earliest days at Wake Forest College, a tradition of prestige and excellence has continued throughout the school’s history in the form of a particular organized activity. That activity is debate. Throughout the years, the debate team has grown and changed, but it has always continued to earn high honors for Wake Forest each debate season. One of the major changes to debate as an activity at the school was the inclusion of women on the team. This change represented the beginning of a whole new era, in which women were allowed to prove themselves to be as successful in public speaking and argumentation as the Wake Forest men that were praised time and time again for their persuasive and oratorical skills. In early years at Wake Forest College, and even before the school became a college but was instead the Wake Forest Institute, the students were required to participate in one of two Literary Societies (Paschal, 527). These Literary Societies were called the Philomathesian Society, and the Euzelian Society. According to George Washington Paschal, “their principal literary concern was their debates” (536). At their society meetings the young men would debate about various social and/or philosophical issues. Ironically, long before women ever participated in these debates themselves, they were in a way included in the debates from time to time by virtue of the topic of discussion. For example, “In the year that Wake Forest opened as a college the Philomathesians were debating the question, ‘Is the education of females as much entitled to the consideration of an enlightened people as that of males?’” (Paschal, 542). Later on, debates were expanded beyond the realm of merely Literary Society activities. A Debate team was formed, and Dr. G.W. Paschal coached the first members. 2 Dr. Paschal was also the faculty sponsor of Pi Kappa Delta, the national honorary debating fraternity (Louden, online). Following Dr. Paschal, the team was coached by Dr. H.B. Jones in 1927, Dr. J. Rice Quisenberry from 1930-1936, Zon Robinson from 19361939, and 1940-1941, Joseph E. Copple for a brief period in 1939, 1940, and Professor A. Lewis Aycock from 1941-1948 (Louden, online). In 1942, while the debate team was newly under the leadership of Professor Aycock, the Board of Trustees made the decision to admit women to Wake Forest College for the duration of World War II.1 This historic change followed on the heels of a changing trend at many other institutions of higher learning in the area (Wake Forest Alumni News, online). Since Wake Forest was no longer a college dedicated only to educating young men, many Wake Forest organizations, social groups, and activities were now open to the women who attended the school. This change meant that women could choose to participate as members of the competitive traveling debate team at Wake Forest. This would allow for a stark contrast from the usual all-male makeup of the team as pictured above. For years it was unclear exactly who the first female member of the team was, but in a recent interview with the author of this paper, a woman named Martha Ann (Allen) 1 Many of the male students at Wake Forest were forced to join the military and fight in the war at this time. Wake Forest was in financial danger due to the extreme drop in the level of applicants and admittance of women was the only viable solution to guarantee that the college did not have to shut down (Wake Forest Alumni News, online). 3 Turnage stated with certainty, “I am one hundred percent positive that I was the first.” She set foot on the campus of Wake Forest College in 1942, and oddly enough she felt right at home. Unlike her other female colleagues, Ms. Allen never felt like the proverbial small fish in a big bowl. “I grew up with seven brothers so boys didn’t scare me,” (Turnage). She was among the first class of coeds, and her roommate, Beth Perry, was actually the first woman admitted to the college (Turnage). Beth Perry was the daughter of one of the Trustees. Ms. Turnage now recalls that there were approximately thirty women and three hundred men in attendance at Wake Forest College during the war years. She immediately immersed herself into the rigors of academic studies at Wake Forest, and she also made the decision to try out for the debate team. In the present day, participation on the debate team is purely voluntary and open to anyone, male or female, who is interested. That was not the case in 1942. “We had to try out for the team, but I made it” (Turnage). Ms. Turnage contributes her success at the team try-outs largely to the fact that she had debated in high school, as she was experienced in the skills required of debaters at the time. For two years, she traveled to debate tournaments around the country with the team (Old Gold and Black, online). The picture to the left of some members of the team and Professor Aycock was taken in 1942. Martha Ann Allen is pictured right in front. This picture likely appeared in the student newspaper. 4 Martha Ann Allen’s achievement did not go unnoticed at Wake Forest College. On April 9, 1943, the student newspaper read: “Coeds are making history on this campus, and this week the oldest extracurricular activity of the school was invaded by a woman for the first time. Accompanying the Wake Forest forensic squad to Charlotte and speaking in the Pi Kappa Delta regional contest there was Martha Ann Allen, who now holds two "firsts" in the debate field. She is the first girl to be invited to join the local chapter of Pi Kappa Delta, national forensic fraternity. And she holds the distinction of being the first member of the weaker sex ever to represent Wake Forest in an varsity debate tournament” (Old Gold and Black, online). In addition to becoming a member of Pi Kappa Delta, and becoming the first woman to travel with Wake Forest to an intercollegiate debate tournament, she was also awarded the school letter in Forensics for the 1942-1943 season. Professor Aycock is quoted as having once told her, “You make me think of a breeze blowing across a field of new- mown hay. Don't ever lose your enthusiasm” (Old Gold and Black, online). In those days debate tournaments followed a little different format than the tournaments Wake Forest attends typically do now. According to Ms. Turnage, “Tournaments weren’t just about debates, there were debates, and parliamentary procedure”. The students competed in multiple different speaking events, and the Wake 5 Forest team always did well. “Professor Aycock used to rent a van and we would all pack ourselves into it and drive to whatever school was hosting the tournament” (Turnage). Martha debated in a two-person cross-examination format, and her debate partner was fellow student and team colleague, John McMillan (Old Gold and Black, online). During the time that Ms. Allen was on the team she may have debated two different topics. Each season a debate topic was chosen in advance so that teams could do research and prepare their arguments before encountering their opponents at tournaments. The topic for the 1942-43 season was: “RESOLVED: That the United States should establish a permanent federal union with power to tax and regulate commerce, to settle international disputes and to enforce such settlements, to maintain a police force, and to provide for the admission of other nations which accept the principles of the Union” (Louden, online). In order to prepare for this topic and to prepare for tournaments Ms. Turnage recalls that the team would hold inter-team practice debates. “We used to debate each other before we went to tournaments, and we had to be prepared for anything because we would never know what side we had to take at the tournament until we got there” (Turnage). Martha ventured out into areas at Wake Forest that no woman had entered before. In addition to becoming the first woman on the debate team, she became the first female editor of the student newspaper, The Old Gold and Black, and she received the highest praises from her faculty advisors (Turnage). Bynum Shaw, a former debater during the time that Ms. Allen was present on the team notes, “Following the lead of Martha Ann 6 Allen, who in 1943 had become the first female editor of Old Gold and Black, campus coeds contributed regularly to student publications and gradually moved into leadership positions” (Shaw, 56). Martha Ann Allen set an example in many ways for the future female students that would enroll at Wake Forest College. She demonstrated that a woman did not have to conform to the traditional domesticated role that most women of the time found themselves locked in. Immediately after receiving her diploma from Wake Forest College, her first job was working as a reporter for the Winston-Salem Journal. Of her post-college career, she says, “In those days women were secretaries or teachers, and everyone used to presume I was one of the two and ask me where I taught or who’s secretary I was. It was quite different for a woman to hold my position” (Turnage). Many things that Martha Ann Allen did were “quite different” from what women did at the time. But her courage and determination to succeed in an academic environment surrounded by men paved the way for many women. Soon after Ms. Allen left Wake Forest, another woman named Betty Stansbury, succeeded her to become the second female editor of the Old Gold and Black. Additionally, not long after Allen left, several more women joined the debate team. In 1946, Nancy Easley competed on the debate team, and in 1948 Lucie Jenkins Johnson did the same (Louden, online). Throughout the years, more women joined the team and represented Wake Forest College, and eventually Wake Forest University, at competitive intercollegiate debate tournaments all around the country. Now the team at Wake Forest has approximately twenty members, seven of which are women. Martha Ann (Allen) Turnage looks upon 7 this female representation with great respect and pride. If not for her, who else might have become the first woman on the debate team, and when? According to Martha, women in her class weren’t exactly lining up to try out, as she explains, “I didn’t know of a single other girl who was even interested in trying to debate on the team at the time” (Turnage). Interestingly enough, there are still many more men in debate at Wake Forest and in debate organizations at most other schools as well, than there are women. Much of this may be due to the fact that “there are many biases which women face in debate (Stafford, online). One woman explains in a symposium on women in debate that there are sadly all too often “accounts of discrimination against women, sexual harassment” in the activity (Bjork et al, online). While such problems may or may not have existed at Wake Forest at the time, one can imagine that the environment in which a woman entered a traditionally male activity for the first time might have presented quite a challenge for her. It is quite remarkable that Martha Ann (Allen) Turnage looks back on her experience as the first woman (and only woman at the time) on the Wake Forest debate team and recalls nothing but positive memories. When asked how she got along with the men on the team, she replied “It would have been difficult for women with less association with the other sex” (Turnage). She added, “I wanted to be a boy when I was younger. I heard that if you kissed your elbow you could be a boy, so I spent years trying to kiss my elbow” (Turnage). She laughed as she quickly explained, “this desire to be a boy promptly ended when I found out that boys eventually had to be in the military” (Turnage). Ms. Allen was as comfortable being the only woman on a team of men as she was being around her seven brothers. 8 Martha Ann (Allen) Turnage accomplished many great things at Wake Forest College, and her level of success never dropped after she left the school. She eventually went on to obtain her Master’s Degree in sociology from The College of William and Mary, and later became the Dean at three community colleges (Turnage). She then served as the Vice-President of two prestigious Universities, George Mason University and Ohio University. She retired in 1992 and now lives in the comfort of her residence in Virginia, while keeping in close contact with her four children and eight grandchildren. Today the Wake Forest Debate team continually enjoys great success and carries on the same proud tradition of honor that was begun with the founding of the Wake Forest Institute. However, thanks to Martha Ann Allen, the history of the team represents a story of diversity in addition to hard work, intelligence, and rhetorical skill. Women who debate at Wake Forest University are proud to look back and learn the story of a young women, Martha Ann (Allen) Turnage, now in her eighties, who had the courage and willpower to enter a territory new to her gender. 9