Structure and performance trends in Irish agriculture

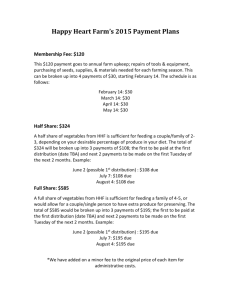

advertisement

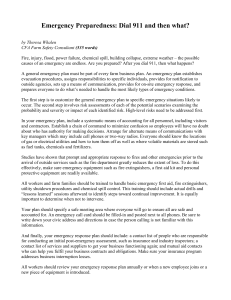

Structure and Performance Trends in Irish Agriculture Paper prepared for the Conference ‘Inside or Outside the Farm Gate? Exploring Strategies for Diversification”, Cork 10-11 April 2003 Alan Matthews Jean Monnet Professor of European Agricultural Policy Trinity College Dublin Introduction Agriculture is living through turbulent times. Rarely has uncertainty about the future been so great. While the CAP has faced budget and other crises before and has been in a state of perpetual reform over two decades, the combination of challenges to the continuation of CAP protection has rarely looked so strong. One source of pressure comes from the WTO agricultural trade talks, part of the Doha Development Round of comprehensive trade negotiations. Participants in these talks, and particularly the EU, the US and developing countries, are still wide apart on the modalities of these negotiations, meaning agreement on the nature of the support reductions which should be pursued and on the numerical targets for the scale of these reductions. The EU’s continued use of export subsidies has come under sustained criticism, while the use of the so-called Blue Box to protect the EU’s compensatory payments from reduction commitments has also been highlighted. Any limitations on the use of either of these instruments would impact seriously on Irish agriculture which has a heavy dependence on both of them. At the present time, the prospects for reaching agreement on the negotiations’ agenda by the self-imposed deadline of September this year at the Fifth WTO Ministerial Conference in Cancun, Mexico does not look promising, and thus these prospective WTO restrictions may not arise in the immediate future. The implications of failure, however, while bringing short-run advantage to the farm sector, could impose much higher costs on the economy as whole. A second source of pressure is the prospective EU enlargement, with membership offered to ten Central and Eastern European countries from 2004. While budget provisions have been made to cover the direct costs of enlargement up to 2013, these costs are not likely to leave much over in the kitty to provide compensation for further CAP price support reductions if these are necessary to reach agreement on a WTO package or otherwise pursued for internal reform reasons. Into this mixture Commissioner Fischler has thrown his Agenda 2000 Mid-Term Review proposals which clearly are influenced by the enlargement and WTO context. One of the motivations behind the proposal to decouple direct payments from 1 production would be to safeguard these payments from reduction requirements as a result of WTO rules. The motivation for another proposal, that of dynamic modulation, is to try to find resources not just to fund a stronger second pillar or rural development component of the CAP, but also to raise funds to enable some compensation to be paid for price reductions in the currently unreformed sectors. Other elements of the Review are intended to try to improve the competitiveness of the cereals and dairy sectors on world markets, making them less dependent on export subsidies and thus less vulnerable to changes in WTO rules. The proposals are also driven by the desire to improve the efficiency of farm income support and to take greater account of consumer and taxpayer concerns around the environmental and multifunctional aspects of agricultural production. While the proposals have met with a hostile response in most quarters in Ireland, they at least map out a coherent strategy in response to the pressures facing the CAP Meanwhile, at home, farm incomes are under pressure and the issue of farm succession has become a hot topic as young people appear to turn away from farming as a career. Against this background, this paper proposes not to engage in further analysis of alternative future scenarios, but rather to look back and examine the trends which have brought us to where we are today. In this, it follows the path set by the very useful paper by Harte (2002). Less than two months ago, the 30th anniversary of Ireland’s membership of the EU, then the European Economic Community, passed virtually unnoticed. Perhaps it is a sign of how thoroughly we now perceive EU affairs as essentially domestic. But it does provide a useful milestone to examine some of the longer-term trends in Irish agriculture which provide the context and background for current debates. Based on this presentation of statistical trends in the main part of the paper, we conclude with some comments on the implications of these trends for the future. Contribution of agriculture to the economy Figure 1 shows the long term trends in the shares of agriculture in total employment and GDP. Employment in agriculture (including forestry and fisheries) has fallen from 22 per cent in 1975 to just under 7 per cent in 2002. The downward trend slowed during the 1980s because of the difficulties which faced non-agricultural 2 employment creation at that time, but resumed its previous trend in the 1990s. However, in 2002, agriculture maintained its share of total employment due to a rise in employment in both the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. What is surprising is that agriculture’s employment share did not fall more rapidly during that ‘Celtic Tiger’ period which saw a remarkable increase in non-agricultural employment. The trend in the share of agriculture’s contribution to GDP follows an almost parallel path, though with greater variability particularly in the first half of the period to 1987. Agriculture’s share has fallen from 18.3% in 1973 to reach 2.7% in 2001. This comparison leaves out the contribution of the rest of the agri-food sector, while comparison with GDP also underestimates the contribution of primary agriculture given the way GDP figures are inflated by the transfer pricing practices of the multinational sector. However, the shift in the importance of agriculture since EU accession thirty years ago has been dramatic, and Ireland is now much less of a European outlier than it used to be. Figure 2 shows trends in absolute employment levels in farming. Two series are shown. The first is the total employment in agriculture, forestry and fishing on a Principal Economic Status definition which only includes those whose principal status is in agriculture. The other series measures labour input into agriculture in Agricultural Work Units (AWU) based on the Farm Structure Surveys; this includes the contribution of those who work only part-time or on a casual basis in the industry. While the absolute levels of the two series differ, the two trends move closely in parallel until 1993, after which there is tendency for the AWU series to fall more rapidly. This provides greater evidence of a ‘Celtic Tiger’ effect than the other series examined. Closer analysis of the AWU figures would reveal whether the greater reduction is due to less full-time involvement in farm work by farm operators, or a greater difficulty in attracting labour other than the farm operator during those years. Indeed, data from the Teagasc National Farm Surveys show that the proportion of farms where both operator and/or spouse have an off-farm job has steadily increased over the past decade, from just over 30% in 1993 to 45% in 2001 (Figure 3). The rate of increase has been slightly faster for the spouse than for the farm operator. 3 Trends in output and inputs Long-run trends in gross output since Irish membership of the EU are shown in Figure 4.1 Two things stand out from this chart. The first is the cyclical pattern of output, with dips or slowdowns occurring after the cattle crisis of 1975, the cost-price squeeze caused by membership of the European Monetary System after 1979, again after 1984 and after 1994. The second feature is the apparent slowing down, indeed almost cessation, of growth after 1992, coinciding with the introduction of the MacSharry reforms. MacSharry is best known for substituting direct payments for part of the market price support provided in the arable and beef regimes. Figure 4 suggests that equally important was the effective ceilings placed on output expansion, partly because of the limits on the number of animals or hectares eligible for direct payments which reinforced the existing quota controls on milk and sugar beet output, but also because of the deliberate incentives for extensification in the beef and sheep sectors and as a result of the introduction of REPS. Figure 5 shows the corresponding trend in the use of intermediate inputs. The sharp rise in the use of inputs in the 1970s led to an anguished debate about productivity trends in agriculture at the time, but over the period as a whole, inputs grew only slightly faster than gross output. The same pattern of a levelling off in input use after 1994 is apparent, mirroring the levelling off in gross output. When trends in gross output and intermediate inputs are compared in value terms, a somewhat different picture emerges (Figure 6). Here the implications of the revision of the agricultural accounts for the interpretation of trends is more serious, and thus the trends are shown separately for both the old and new series. In both cases, there is a steep upward trend in the share of inputs to gross output, measured at market prices (old series) or producer prices (new series). The sharp acceleration took place after 1992, reflecting the fact that direct payments became an increasingly important part of 1 In charting long-term trends, the revision of the methodology to construct the agricultural output, input and income figures to bring it into line with the 1995 revision in the European System of National Accounts needs to be taken into account. 4 farmers’ returns after that date. Because the payments were coupled to production, farmers had to maintain production (and thus input use) even though market returns were falling. The significance of this chart is what it tells about the likely impact of decoupling on input use which looks like it will fall back from 60 percent of output value to 40 per cent of output value were decoupling introduced on the basis of historic trends. The motor of Irish agriculture is the cattle sector, both dairying and beef, and the engine is the size of the breeding herd. Figure 7 shows the evolution of cow numbers in the period since EU membership. Two sub-periods can be distinguished. The first is the remarkable stability in total cow numbers during the period 1975 through 1987, at time when GAO was growing rapidly. Dairy cow numbers increased but only very slightly up to 1984, since when there has been a steady decline. Suckler cow numbers declined throughout the second half of the 1970s and stabilised in the first half of the 1980s, but increased by almost 150% between 1987 and 1998 after which numbers have stabilised again. This astonishing increase in the suckler herd over this decade is rarely commented on. It was due, in part, to the milk quota restrictions on dairy farmers, but must also have reflected the growth of direct subsidies, even though these subsidies were mainly compensating for reductions in market price support and thus there was no real improvement in suckler gross margins over this period. Total cow numbers peaked in 1998 at 2.44 million, probably the largest number of cows we will ever see in this country. Even the 30% fall in suckler cow numbers predicted to follow from introducing the decoupling proposal (FAPRI-Ireland, 2002) would only bring their numbers back to the pre-MacSharry level, which in itself was more than double the average number in the 1970s. Sheep and pig numbers follow a similar trend (Figure 8). Sheep numbers were gently declining in the second half of the 1970s until the opening of the French market in 1980 led to a huge expansion in sheep numbers, which more than doubled over the next decade. Sheep numbers peaked at 6.1 million in 1992 and since then have fallen 5 to 4.8 million or a drop of 27%. Pig numbers were static until somewhat later, but rose sharply in the decade 1987-1999, after which they have stagnated again. Total cattle numbers follow directly the trend in cow numbers (Figure 9). It does look from the graph as if cow numbers have increased slightly faster than cattle numbers, but this may be an artifact of using two different scales. Cattle output per cow has in fact declined slightly over the period. Milk output per dairy cow increased steadily up until about 1991 after which the growth in yields appears to have levelled off (Figure 10). Trends in farm income Trends in farm incomes are a function of trends in output, prices and increasingly, in direct payments. Price trends are shown in Figure 11 for the years since 1980. What is striking is the way output and input price trends diverge after 1994, when the price reductions introduced by the MacSharry CAP reform and continued in Agenda 2000 began to take effect. As a result, there has been a marked deterioration in farmers’ terms of trade since then. However, as an indicator of income trends, these terms of trade movements are misleading because they do not take account of the increase in direct payments which substituted for the reduction in prices. Trends in aggregate income from farming and the growing importance of direct payments are shown in Figure 13. Income is expressed in real terms by converting into constant November 1996 prices. After a sharp fall in incomes in 1975 due to the cattle crisis in that year, income recovered quickly and peaked at €3.5 billion in 1978, a figure never again reached in the post-EU membership period. Income fell dramatically in the next two years by 40% after which they began a slow, if cyclical recovery to reach a further, but lower, peak in 1996 of €2.8 billion. Since then, aggregate income has fallen in real terms and continued to fall in 2002. A trendline through the data suggests a steady fall in aggregate income from farming over time, despite much volatility around this trend. This fall in aggregate income from farming does not reflect the trend at individual farm household level. First, as shown earlier, there has been a steady decline in 6 agricultural employment so that the aggregate farm income is shared among fewer persons over time. Second, as also shown earlier, there is a much greater prevalence of off-farm work thus ensuring a growing importance of off-farm income in the total income of farm households. This fall in aggregate income has occurred despite the growing importance of direct payments. Direct payments have increased steadily since the early 1990s; the apparent fall in 1999 is due more to a statistical break in the way the figures are constructed which underestimates the size of direct payments in those last three years.2 Direct payments only tell part of the story of farm income support; within the balance of income from market activity there remains a considerable amount of indirect support, due to way market prices continue to be protected and maintained above world market levels. Indeed, if indirect and direct support to Irish agriculture is aggregated, it amounts to nearly all of the income arising in the sector (Matthews, 2001). Trends in farm structures This section examines changes in the underlying structure of farming since EU accession. Figure 14 shows trends in the number and average size of farms. The series was revised in 1991 based on farms rather than holdings, and the minimum size threshold was raised from 1 acre to 1 hectare. Thus data prior to 1991 cannot be compared with the data after that year. In the decade since 1991, the number of farms has declined smoothly in line with the decline in employment; indeed, the rate of decline was slower in the second half of the 1990s (8.4% drop in the 6 years 19952000 compared to 11.2% drop in the 5-year period 1991-1995). This slowdown in the rate of farm reduction and amalgamation is somewhat surprising in the face of the Celtic Tiger boom, and the jump in average farm size in 2000 despite no apparent increase in the rate of decline in farm numbers suggests another anomaly which needs further exploration. 2 The official statistics in the new system of agricultural accounts aggregate subsidies not related to production and taxes, so the figures post-1999 are on a net basis as opposed to the gross figure for direct payments for earlier years. 7 Data on changes in numbers in different farm size groups over time can be used to infer the minimum average viable scale of farm using what is called the ‘survivorship approach’. The basic assumptions of the approach are that farm income should rise with the average size of farm, and that there should be a correspondence between differences in profitability of various size groups and changes in the numbers of farms in each group. If small farms have to struggle to keep going, one would expect their number to gradually decline and the number of farms at or above some economically viable size to increase. Further, it might be expected that the pressure of competition for land would squeeze out the smallest farm business most rapidly, the somewhat larger farms less rapidly, and so on, until a size could be identified at which the number of farms being absorbed into larger, more economic, units was just about balanced by the number that were attaining that size by the process of absorption of smaller units. This reasoning suggests that there is a break-even point which could be taken to represent a minimum size for economic viability. The trend would show a decrease in the number of farms below that size and an increase in the number above it. Furthermore, as agricultural technology and enterprise profitability changes, the minimum size for viability will itself be changing over time. Figure 15 finds some support for these contentions. It shows the percentage change in the number of holdings enumerated in each size group for four periods. Taking the 1975-1980 period first and ignoring the growth in farms under 5 ha as being an anomaly, the transition group separating those farm sizes in which numbers are declining from those where they are increasing is the 20-30 ha size group, and the chart line crosses the breakeven axis at about 25 ha. The data for 1980-87 are less easy to rationalise. They suggest a small increase in the minimum viable size (the breakeven point is a little to the right of the 1975-80 point) but the 30-50 ha size group and the over 100 ha group also appear to be declining. Only in 1991-95 (based on the new census methodology) do we fully observe the ‘expected pattern’. The breakeven point has now clearly moved to the right and the minimum viable size appears to be around the 50 ha mark. The data for the most recent 1995-99 period 8 confirm this shift in the breakeven size and suggest there has been a further small shift to the right in this minimum size. Again, however, the number of the very largest farms does not appear to have increased in line with expectations. This apparent doubling of the minimum viable farm size over the past two decades is mirrored in the data on structural change for the major farm enterprises. Details are given for dairying, suckler cows and pigs for illustration (comparable data for sheep flocks are not available). In dairying, for example, the total number of holdings with dairy cows has fallen from 144,000 in 1973 to 32,000 in 2000 (Figure 16). At the same time, the average size of dairy herds has increased from 10 cows to 37. Trends in the structure of pig herds show an even more dramatic change. While the number of holdings with pigs has fallen from 35,700 in 1973 to 1,300 in 2000, the average number of pigs per holding has increased from 20 to 1,345 (Figure 17). Against this background, the lack of change in the suckler enterprise is striking, and is perhaps confirmation of the residual nature of this enterprise in Irish agriculture. The total number of suckler cow herds fell from only 95,000 in 1973 to 84,000 in 2000 (90,000 in 1999) while the average size of herd has only doubled, from 7 to 14 (Figure 18). The final trend to highlight with respect to farm structure is the declining role of the land market in structural change. The volume of land transactions was never large in Irish farming, but has steadily fallen throughout the 1990s at the same time as land prices nearly tripled from €4,800 per ha in 1991 to almost €14,000 in 2001 (Figure 19). The first signs of easing appeared in 2002 when (in the first three quarters) average prices fell back to €12,500 and sales increased. These damaging trends (from the point of view of structural change) are often blamed on the sale of development land around towns and cities driving up the price of agricultural land. I would argue that it is much more to do with perverse policy incentives which have linked support payments to land and created an artificial value for land for extensification and REPS eligibility purposes. Conclusions The previous sections have presented a largely factual picture of structure and performance trends in Irish agriculture since EU membership 30 years ago. In this 9 concluding section, we enter more speculative mode to ask what conclusions can be drawn from this retrospective look at long-term trends. I suggest there are at least three important lessons. First, the growth momentum of Irish agriculture now appears to be exhausted. Steady growth of 2.5% per annum between 1973 and 1993 has now petered out and output has stagnated since then. The reason for this is not the exhaustion of the potential for productivity growth – indeed, technical change in some farm enterprises continues at a respectable rate. Rather, it appears to reflect increasing policy constraints and changing policy priorities since 1993. The constraints refer to the ceilings on the number of animals and hectares eligible for support. While these ceilings do not prevent increased production in the way that milk and sugar quotas do, they nonetheless curtail expansion through creating artificial barriers to increased scale at farm level (the need to purchase suckler cow and ewe quotas) and by raising input costs to a level which makes additional unsupported production uneconomic. Perhaps more important is the change in policy priorities. From the single-minded pursuit of increased production of farm commodities, agricultural policy is now pursuing an increased number of, often conflicting, policy objectives. Extensification conditions and stocking density restrictions clearly militate against further increases in farm output. These measures are introduced in the name of achieving greater environmental sustainability, though they are motivated as much by the need to restrict EU production to the limits of what can be absorbed by the domestic market plus the allowed amounts of subsidised exports under WTO rules. Whatever the motivation, further restrictions arising from the introduction of nitrate vulnerable zones and the need to curtail livestock numbers in order that agriculture makes its contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions are in prospect. At the same time, if the elimination or even reduction of export subsidies were agreed in the Doha Development Round of WTO negotiations, and if improved market access were offered to the EU market to third countries, these would seriously reduce the economic incentive to increased production. If the decoupling of direct payments were agreed as part of the Mid-Term Review, this would add further to the downward pressures on output. Thus the ceiling on agricultural production appears to be more 10 than a short-term phenomenon, with consequent implications for the levels of activity in the food processing and input supply industries. The second lesson concerns income trends and prospects. If the 1970s are ignored, real income from farming has remained more or less constant in the past two decades. But the composition of this income has changed dramatically, with a significant fall in marketplace returns and a corresponding increase in the relative importance of direct payments. However, the EU’s ability to continue to pursue the MacSharry and Agenda 2000 reform philosophy of compensating farmers for reductions in support prices through increased direct payments is in doubt. The budget ceiling for CAP income and market support is now in place until 2013. Once the additional expenditure to extend direct payments to farmers in the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe is accounted for, there is virtually nothing left to compensate farmers in the EU15 for further reforms of the unreformed sectors. Commissioner Fischler has recognised this reality in the January 2003 version of his MTR proposals, by suggesting the modulation of current direct payments to create an additional pool of cash from which to provide such compensation. But while this may lead to greater equity within the farm sector, it is only robbing Peter to pay Paul and does nothing to raise the overall level of income available from farm production. A peculiar Irish problem which will have a serious adverse effect on the real value of these payments in the next few years is the high rate of inflation here which will rapidly erode the real value of existing direct payments which are now accounting for two-thirds of aggregate income from farming. These considerations suggest that, as in the past decade, an increasing proportion of the income of farm households will come from off-farm sources as these households attempt to diversify to more remunerative activities. The third lesson concerns the prospects for structural change. The evidence presented here on structural change in the post-EU membership period presents an ambiguous picture. On the one hand, there is evidence of rapid structural change at the individual enterprise level, illustrated here in dairying and pig production, but evident also in other sectors such as cereals, root crop and horticultural production. Evidence was also presented that the minimum viable size of farm has increased from 25 ha to 50 ha over the last two decades. But on the other hand, the stability in the long-term decline 11 in farm numbers and farm employment, despite the dramatic changes in the off-farm employment context between, say, the 1980s and the 1990s in Ireland, is remarkable. One of the keys to understanding this paradox appears to be the role played by the suckler cow herd and possibly also sheep production in allowing some farmers to retain occupation of their land while their main income source comes either from offfarm employment or social welfare payments. As has been commented previously (Boyle 2002), the beef sector has become a residual enterprise in Irish agriculture and would be hopelessly uneconomic in the absence of current subsidies. The difficulty is that these payments have become capitalised into the price of land and have led to the constipation of the land market, with adverse consequences for new and expanding farmers and thus the future competitiveness of the agricultural sector. There is clearly a trade-off here, as government policy seeks to maintain the maximum number of family farms albeit through supporting what has been an uncompetitive enterprise. It would be more desirable to use these funds to stimulate and encourage viable alternative opportunities and enterprises to keep people in rural areas. It is for this reason that I welcome the conference theme today ‘Exploring Strategies for Diversification’ and hope it will lead to a stimulating and productive discussion. References Boyle, G., 2002. The Competitiveness of Irish Agriculture – Final Report, Dublin, Department of Agriculture and Food. FAPRI-Ireland, 2002. An Analysis of the Effects of Decoupling Direct Payments from Production in the Beef, Sheep, and Cereal Sectors (Binfield, J. et al), Dublin, Teagasc. Harte, L., 2002. Questioning Agricultural Policy in the Modern Irish Economy, Paper read to the Agricultural Research Forum, March 2002. Matthews, A., 2001. How important is agriculture and the agri-food sector in Ireland?, Irish Banking Review Winter 2001, pp. 28-40. 12 Figure 1 Agriculture's employment and GDP shares, percent 26% 24% 22% 20% 18% 16% 14% 12% 10% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 Figure 2 Labour force in agriculture, thousands 400 350 300 250 2 200 150 100 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 Total AWU Employment in Agriculture, forestry & fisheries 13 Figure 3 % of farm households with off farm job, 1993-2001 50% 45% 40% 35% 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 Holder or Spouse 1998 Holder 1999 2000 2001 Spouse Figure 4 Gross Agricultural Output Index, 1995=100 110 105 100 95 90 85 80 75 70 65 60 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 14 Figure 5 Intermediate consumption index, 1995=100 110 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 Figure 6 Ratio of input use to output, per cent 80 70 New series 60 Per cent 50 40 I 30 20 10 0 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2002 15 Figure 7 Cow Numbers (thousands) 2,500 2,000 1,500 1,000 500 0 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 Dairy cows Other cows Total cows Figure 8 Total sheep and pig numbers, thousands Dec census 250 7000 Pig nos (thousands) 5000 150 4000 3000 100 2000 50 1000 0 0 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 Total pigs Total sheep 16 Sheep nos (thousands) 6000 200 Figure 9 Cow and cattle nos, thousands, Dec census 2500 7500 2400 7000 2300 2200 2100 6000 2000 5500 1900 Total cows Total cattle 6500 1800 5000 1700 4500 1600 1500 4000 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 Total cattle Total cows Figure 10 Yield (Kg per Cow) 4,500 4,000 3,500 3,000 2,500 2,000 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 17 Figure 11 Agricultural output and input prices and terms of trade, 1995=100 120 110 100 90 80 70 60 50 1970 1972 1974 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 Agricultural Output Price Index Agricultural Input Price Index Terms of Trade Figure 12 Real income from agriculture, € million Nov 1996 prices 4000 3500 3000 2500 2000 1500 1000 500 0 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 Real Income Index Real direct payments 18 Figure 13 Number (thousands) and average size of farms (ha) 240 35.0 220 30.0 200 25.0 180 20.0 160 15.0 140 10.0 120 5.0 100 0.0 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 Figure 14 Changes in farm size structure, per cent change in various periods 5.0 0.0 -5.0 % -10.0 -15.0 -20.0 -25.0 <5 ha 5-10 ha 1975-1980 10-20 ha 20-30 ha 1980-1987 30-50 ha 1991-1995 50-100 ha >= 100 ha 1995-1999 19 Figure 15 160 40 140 35 120 30 100 25 80 20 60 15 40 10 20 5 0 Average herd size No herds, thousands Structural change in dairying 0 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 2000 Total Holdings with Dairy Cows Average size of herd Figure 16 Structural change in the pig herd 40 1,600 30 1,200 1,000 20 800 600 10 Herd size, nos Herd no, thousands 1,400 400 200 0 0 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 2000 Total Holdings with Pigs Average size of herd 20 Figure 17 Structural change in suckler herds 16 14 100 12 80 10 60 8 6 40 4 20 2 0 Average no. cows No. herds, thousands 120 0 1973 1977 1981 1985 1989 Total Holdings with Suckler Cows 1993 1997 Average size of herd Figure 18 Land transactions 35,000 16,000 30,000 14,000 12,000 10,000 20,000 8,000 € hectares 25,000 15,000 6,000 10,000 4,000 5,000 2,000 - 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002e Aggregate Area Sold Average Price 21