DELIRIUM

advertisement

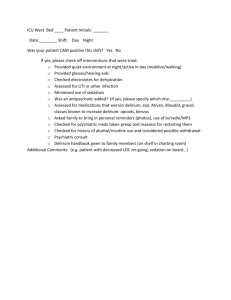

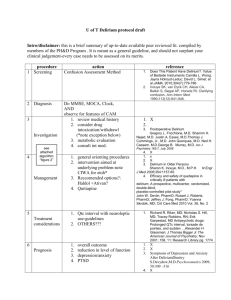

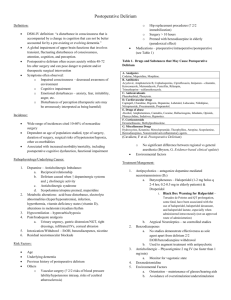

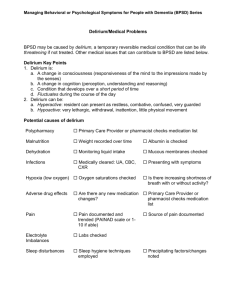

Care Management Guidelines Delirium Page 1 of 8 Delirium Introduction Delirium is not a disease nor a symptom, but a complex syndrome with multiple causes. It is a frequent and serious complication of advanced illness affecting up to 48% of patients with advanced cancer, and up to 90% of all patients in the last hours or days of life but is overlooked in up to 66% of cases. It is often associated with organ failure, and carries a poor overall prognosis. Suffering may be severe yet overlooked, especially in hypoactive delirium. It has a high impact on families and carers: it is a common cause of breakdown of care at home and is a common cause of emergency hospital admission. Key Principles Failure to recognise delirium is common. Identify those at risk - Screen and assess with the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) tool Potentially modifiable causes or aggravating factors are common and often iatrogenic. Early Intervention: 50% of patients with hypo-active delirium progress to a hyperactive state unless adequately treated, or the causes are easily modified. Neuroleptic (antipsychotic) agents are the first line drug class of choice; ensure access to prn doses, even when regular doses are commenced. Benzodiazepines are used: o As first line agents for delirium associated with seizures or alcohol withdrawal. See Terminal Care Guidelines for information terminal restlessness. o As second line agents for escalating agitation; and where sedation is required for the benefit or safety of the patient. Review frequently. In a reversible delirium the natural lag time between the removal of causative factors and improvement may lead to drug-induced over-sedation. Ensure you have a back up plan for unstable symptoms, unsafe behaviours, or an unsustainable environment. Assessment The family and caregivers are often the first to notice subtle changes in behaviours and can give a history of what is normal for the patient. Assessment needs to determine cause, impact on quality of life of the patient and their family, and effectiveness of interventions. Ongoing comprehensive assessment is the foundation of effective management of delirium including interview, physical assessment, medication review, medical review and appropriate diagnostics, sleep patterns, psychosocial review, and review of the physical environment. Page 2 of 8 Identifying Patients at Risk Previous delirium. History of significant drug and alcohol exposure. Rapid escalation of opioid dose (e.g. morphine - particularly if frail, elderly with renal impairment, reduced oral fluid intake, and previously opioid naive). Brain injury/failure: dementia, cerebral tumour, CVAs, significant head injury. Organ impairment/failure: renal, hepatic, cardiac, lung. Frail aged, hearing or visually impaired, immobile. Recurrent sepsis: UTI, chest, cellulitis, gangrene. At risk of hypercalcaemia (bone metastases, malignancies: breast, prostate, lung, myeloma, etc.). Multiple medications, especially those with anticholinergic effects. Sleep deprived. Nicotine withdrawal. Potentially Modifiable Causes or Aggravating Factors Causal Metabolic e.g. hypercalcaemia, dehydration, hypo/hyperglycaemia; Sepsis e.g. Urinary tract, chest infection; Severe hypoxia; Drug side effects or toxicity eg steroids, digoxin, anticholinergic load, accumulation of morphine metabolites due to impaired renal clearance, states of serotonin excess; Withdrawal states e.g. opioid, alcohol, benzodiazepine, nicotine, antidepressant. Aggravating Pain; Constipation; Urinary retention – this should always be excluded. Factors likely to be associated with irreversibility Advanced organ failure (brain, liver, renal, cardiac, lung); Advanced metabolic failure (e.g. hypercalcaemia, hyponatraemia); Cerebral malignancy; Advanced sepsis (e.g. inoperable gangrene, peritonitis, pneumonia); Encephalopathy (hepatic, hypoxic) etc. Diagnosis Delirium can be misdiagnosed as dementia or depression. Use the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) tool. Presence of (1) and (2) and either (3) or (4) is required to firmly diagnose delirium: o (1) acute onset, fluctuating course; and o (2) impaired attention, impaired focus of concentration (initiating, maintaining, shifting focus at will); and o Either (3) confusion or any impaired cognition; or o (4) altered consciousness: alertness/activity Page 3 of 8 Management When deciding whether to investigate and treat underlying causes if present, consider if this would be: o appropriate to goals of care and stage of illness; o realistic and reasonably likely to be achievable; o likely to improve quality of life; o overly burdensome; and o consistent with patient’s understanding and wishes/advanced directives. Goals of management Preservation of patient dignity, comfort and safety; Reduction of carer stress and distress; Modification of aggressive and disruptive behaviours; Improvement of sleep quality; and Identify and treat underlying cause or aggravating factors where possible. Non Pharmacological Management “A failing brain, like a failing heart, benefits from the reduction of its workload” Sandy McLeod Environment: Familiar environment where possible; Familiar carer/s present, familiar objects may be reassuring; Night light to assist with orientation; Reduce unnecessary stimulation - loud speech or an over-stimulating environment e.g. avoid TV news; Avoid, if possible: o ambiguous actions e.g. suddenly waking patient in poorly lit room; and o sudden moves or approaches which may startle the patient. Plan for frequent rest periods for patient – and carers; Safety: determine ease of access to investigation, care and need for extra support services to be mobilised Involve patient and carers in decision making: Clarifying goals of care; Whether to investigate; Whether to treat potentially modifiable causes; Place of care; and Developing a plan of care and support for patient and carers. Information and explanation for patient and carers needs to include: That the patient is not choosing this behaviour. Causes are illness progression, complications, etc. The behaviour observed: especially drowsiness, irritability, agitation, confusion, illusions, hallucinations (e.g. visual, tactile, auditory), bizarre thinking, delusions, incomprehensible speech, emotional lability, etc. Emphasis on the fluctuation over time of symptoms, behaviour and severity. Page 4 of 8 This may or may not be reversible: explain possible causes. Why and how neuroleptics (antipsychotics) and sedatives are used: o regular and prn doses; and o ensure ready access to medication. What to do/who to call if the plan is not working. Suggestions for how to respond to unusual behaviour: Don’t dismiss, collude, react strongly, or make fun of the patient. Instead, it may be helpful to gently, briefly acknowledge what the patient is likely to be experiencing and any accompanying emotion or distress observed in the patient. Briefly give reorientating information whatever feels appropriate e.g.: o identify yourself – i.e. who the carer is; o where you both are, what is happening; o why you are here; o what you are doing or about to do. Always allow time for the patient to process the information: o use simple and brief sentences; and o understand that the patient’s response may be delayed. Pharmacological Management Principle drug classes used: Antipsychotic agents: o Butyrophenones o Phenothiazines o atyptical Sedatives: o Benzodiazepines First line treatment Haloperidol is the drug of choice. o It is inexpensive and available on the PBS. o Duration of action: initially 8 - 12 hrs, but up to 24hrs once steady state achieved. o Oral or subcutaneous routes are reliable for regular and PRN doses. o Continuous subcutaneous infusion via syringe driver may also be used to deliver continuous cover. o Titrate dose to effect: doses of more than 2mg/24 hr are rarely required unless delirium is severe. o Watch for akathisia, extra pyramidal side effects (EPSEs), and the need for sedation. o Side effect profile is excellent if low doses used: If up to 5 mg/24 hr: minimal or no sedative effect, minimal anticholinergic burden, no drop in blood pressure. Likely to have less effect on heart than droperidol, olanzepine, etc. If used in doses >3-5mg/24 hr there may be increased risk of akathisia: motor restlessness, EPSEs (Parkinsonism, especially rigidity). Page 5 of 8 o o o o Mild symptoms Night time vivid dreams and mild confusion 0.5mg nocté, and 0.5mg prn. Maximum 2mg/24 hrs Day time hypoactive delirium 0.5mg mane and 0.5mg prn. Maximum 2mg/24 hrs Moderate symptoms Hyperactive delirium 0.5 to 1mg tds, and 0.5mg prn. Maximum 10mg/24 hrs per day Severe Symptoms Doses usually are higher initially 5mg/24hr, up to 20mg/24 hrs Sedation with an appropriate benzodiazepine may be temporarily needed: Option 1: Replace haloperidol with a sedating neuroleptic e.g. Olanzepine (see below) Option 2: Add an appropriate benzodiazepine in addition to regular and prn neuroleptic (unopposed benzodiazepine may exacerbate delirium e.g. in hepatic encephalopathy) Short acting sedation (2 - 3 hrs): - prn midazolam 2.5mg sc - rarely doses of 5mg or greater are required Longer acting (8 - 24 hrs, and will accumulate): - prn clonazepam 0.25mg (0.1ml of 2.5mg/ml solution) buccal, prn 612 hrly or 0.25mg sc, prn - rarely higher amounts or more frequent doses may be required, e.g. clonazepam 0.5mg (0.2ml of 2.5mg/ml solution) buccal or 0.5mg sc Crisis intervention of severe agitated delirium Give extra neuroleptic and sedation initially. Haloperidol 10mg sc stat, or chlorpromazine 100 - 200mg IM or PR stat AND midazolam 5 - 10mg sc stat or clonazepam 1mg sc stat Consider starting S/C infusion of haloperidol 5 - 7.5mg per 24 hrs and midazolam 20 - 40 mg/24 hrs. Assess for increased risk to safety, or reduced capacity of carers to deliver care, and consider admission if: - Patient no longer agrees to the plan of care or treatment, despite escalation of mixed or hyperactive type of delirium. - Carer no longer feels able to deliver care (e.g. fatigue, distress, feels unsafe). - Patient or carers refuse to remove weapons or other sources of danger from the home. 2nd line treatment Risperidone non sedating single agent for mild/moderate symptoms: o Oral route, tablets and orally disintegrating ‘quicklets’. o Doses: regular dose: 0.25mg (- 0.5mg) oral bd, and prn 0.25mg, up to 4 doses in 24hrs. total dose: may require between 0.5 - 3mg/24 hr. Page 6 of 8 Excellent side effect profile in usual doses: non sedating, no EPSEs, no akathisia, very little anticholinergic side effects. Note: using doses >1mg/24 hr does increase the risk of EPSEs and akathisia appearing in the frail elderly. Olanzepine sedating single agent for mild to moderate symptoms: o oral or buccal (soluble wafer) o Doses: regular dose : 2.5mg-5mg oral or buccal (half - one x 5mg wafer) bd; and prn 2.5mg oral or buccal. Total dose: may require between 5-20mg/24 hr. o Multiple sites of action: Serotonin, 5 HT, Dopamine antagonists, anticholinergic muscarinic; adrenergic alpha; histamine H1. o Side effect profile: sedating effect may be useful; little or no risk of EPSEs or akathisia; anticholinergic effect may be significant, especially at doses >10mg/24 hr. o 3rd line where sedation and anti nausea action is required Methotrimeprazine (levomepromazine) o Doses oral or subcutaneous regular dose: 25 - 50 mg po or sc bd, and prn 12.5 - 25mg po or sc; Total dose: 50 - 300mg CSCI 24/24hr. o Potent D2 antagonist, alpha1 antagonist, potent 5HT2 antagonist side effects; sedating; dose dependent postural hypotension; extra Pyramidal Side Effects; potent antiemetic; or analgesic. Consultation and Advice Consider seeking advice if: Assistance required determining modifiable causes of delirium. Opioids suspected as major contributing cause. Delirium not responding to usual doses of haloperidol – first line approach. Patient lives alone or has limited supports. Patient has Parkinson’s disease or develops EPSEs or akathisia with usual dose of haloperidol. Patient has moderate to severe symptoms, especially where sedation may be required. Any risk to patient or carer safety. Carer stress and respite needs. Hospitalisation is being considered for investigation, interventions or safety. Treatment of underlying cause requires specialist assistance e.g. hypercalcaemia. Page 7 of 8 Definition of Terms Delirium is an acute organic brain syndrome, characterised by sudden onset (hours or days) of disordered attention and arousal - a reduced ability to focus, sustain or shift attention. It may be accompanied by disturbances of cognition, psychomotor behaviour and perception. It has a fluctuating course and lucid intervals may occur. There are three main clinical categories of delirium: o Hypoactive: Easily missed or misdiagnosed as depression or fatigue. Quiet, passive, withdrawn, drowsy, can’t concentrate. o Hyperactive: Not missed. Irritable, vigilant, restless, agitated, has insomnia. o Mixed with fluctuations between hypo-active and hyper-active: the most common type of delirium. [1] Other clinical terms include: o Dementia: distinguished from delirium by its gradual onset, and being a disorder of cognition, with no alteration to arousal or attention. o Confusion: altered mental state, cognitive impairment. o Restlessness: inability to relax or be still; ceaselessly moving or a feeling of agitation expressed in motion. o Terminal restlessness: agitated delirium in a dying patient, frequently associated with impaired consciousness and non-purposeful movement. Revision history and planned frequency Endorsed September 2009 Next review September 2010 Page 8 of 8