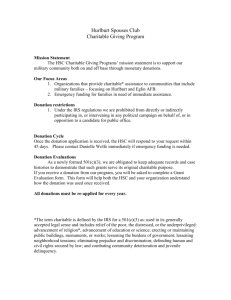

- The University of Sydney

advertisement