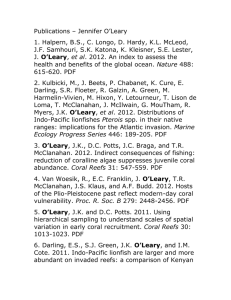

Biography

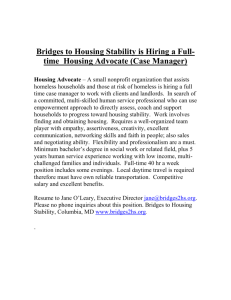

advertisement