HOMINID EVOLUTION Hominid Evolution consists of a series of

advertisement

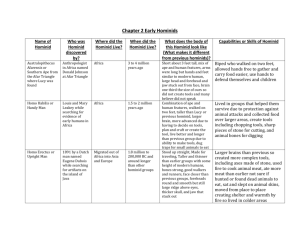

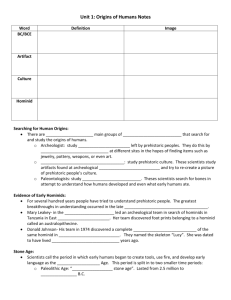

HOMINID EVOLUTION Hominid Evolution consists of a series of sequential Adaptive Radiations: I. FIRST ADAPTIVE RADIATION was precipitated by the Terminal Miocene Event (cold, dry, arid period about 5.3 mya) and produced an array of potential possible LAST COMMON ANCESTORS for hominids and the chimps. Among these late Miocene species, two are particularly important: Sahelanthropus tchadensis: 6 to 7 million year old species from north central African country of Chad. The species is known only from fragmentary skull, mandible, and tooth remains. While some paleoanthropologists believe S. tchadensis walked upright, others disagree and think it was a form of ape. Orrorin tungenensis: 6 million year old species from the Tugen Hills region in Kenya, east Africa. The species is known only from fragmentary postcranial remains: femur, humerous, jaw, and teeth. There is disagreement as to whether this species was an upright or opportunistic biped. We know very little about the life ways of either species; however, we do know that they were forest adapted. II. SECOND ADAPTIVE RADIATION occurred around 4 to 5 million years ago and produced a number of true hominid genera and species during the early Pliocene (cooler and drier grasslands). Among these hominids, two species are notable: Ardipithecus ramidus: 4.5 to 5.5 million year old species from Ethiopia. The species is known only from fragmentary cranial and postcranial remains. It is the most ape-like true hominid yet to be found. It inhabited open forests and woodlands. Australopithecus anamensis: 4.2 to 3.9 million year old species from Kenya. Both ape-like and human-like features, but clearly a biped. It inhabited open forests and woodlands. May represent the ancestor of all later hominids. We know very little about the life ways of either species; however, we do know that they were forest adapted and fully bipedal. However, their form of bipedalism was not exactly like ours. III. THIRD ADAPTIVE RADIATION occurred between 3 and 4 million years ago and produced a number of hominid species and at least one new genera during middle Pliocene (even colder). Among these hominids, the following are important: Australopithecus afarensis (“Lucy”): 3 to 4 million years old. All fossils come from East Africa. The species exhibits sexual dimorphism and habitual upright bipedalism. Males were slightly larger than females (4 to 5 feet vs. 3.5 to 4 feet; 65 lbs. vs. 45 to 50 lbs.) and possessed a small sagittal crest along the top of the skull 1 (for the attachment of chewing muscles). Brain size was about the same as a modern chimpanzee. A. afarensis has some ape-like physical features. Little is known about this species’ life ways, except some of them lived in open woodlands and along wooded streams in the savannas. Though no tools have been found with this species, it is possible they possessed a toll-culture like that of modern day chimps. On the basis of dental wear, their diet included large amounts of fruit and other soft, easily chewed foods. Australopithecus africanus: 2.5 to 4 million years old. Fossils come primarily from South Africa (at least one possible fossil has been found in East Africa). They were habitual upright bipeds. Little is known about this species’ life ways, except some of them lived in open woodlands and along wooded streams in the savannas and perhaps ventured onto the open savannas. Though no tools have been found with this species, it is possible they possessed a toll-culture like that of modern day chimps. On the basis of dental wear, their diet included large amounts of fruit and other soft, easily chewed foods. Kenyanthropus platyops: 3.5 to 3.2 million years old. Shows a combination of features like those of A. afarensis and A. africanus and foreshadows early Homo. All specimens come from Kenya. They were habitual upright bipeds with brain size about the same as modern chimps or a little larger. Little is known about this species’ life ways, except some of them lived in open woodlands and along wooded streams in the savannas and perhaps ventured onto the open savannas. Though no tools have been found with this species, it is possible they possessed a toll-culture like that of modern day chimps. On the basis of dental wear, their diet included large amounts of fruit and other soft, easily chewed foods. Some paleoanthropologists have suggested that K. platyops is a better candidate for the direct ancestor of Homo than any of the Australopithecines. IV. FOURTH ADAPTIVE RADIATION occurred between 1 and 3 million years ago and produced a number of hominid species and at two new genera during the late Pliocene (still cold). Among these hominids, the following are important: Paranthropus boisei & Paranthropus robustus: 2.2 to 1 million years old. P. boisei lived in East Africa, and P. robustus lived in South Africa. Their brains were the size of those of modern chimps. Their bodies were small like earlier hominids. Their faces, jaws, and teeth were large due to their diet of hard-to-chew foods. Their diet included seeds, nuts, and roots. They lived in dry savannas and woodlands and may have used tools to dig for roots during the dry seasons. Australopithecus garhi: 2 to 3 million years old. Lived in East Africa. Mixed apelike and human-like traits. Fossils found alongside antelope, horse, and other animal bones that had been butchered for meat and shattered for marrow. Possibly the first meat-eating species. Also, possibly first species to make stone tools. V. FIFTH ADAPTIVE RADIATION occurred at the end of the Pliocene, coinciding with the beginning of the first great ice age (climatic fluctuations and glaciation 2 to 1.8 mya) and produced a number of hominid species within the genus Homo. 2 Early Homo: 2 to 2.5 million years old. They are distinct from all previous hominids in the following ways: o Brains are nearly 50% larger o Less facial prognathism (snoutiness) o May have had rudimentary human language skills o Made stone tools o Added meat (scavenged from predatory kills) to their diet o Occupied a number of different habitats (open woodlands, forests lining savanna rivers and savannas) across eastern and southern Africa Homo habilis: 2.3 to 1.5 million years old. They were the first known species to make and use stone tools, Oldowan tools, consisting of sharp flakes knocked off a larger stone core (the leftover core also became a tool). While the exact use of the tools is open to debate, some tools were used to cut meat off of bones and the cores used to smash open bones to get the marrow. Little is known about this species’ life ways or social patterns. They ate fruit, nuts, flowers, and salad and occasionally scavenged meat from the kills of predators. NOTE: The Paranthropus and early Homo forms lived side by side. It is not known, however, whether they recognized each other as hominids. Then, around 1 mya (for unclear reasons) the robust Australopithecines became extinct, leaving only various species of Homo. Homo ergaster: 1.8 to 1.6 million years old. This species has only been found at Lake Turkana in Kenya. The brain size is greater than H. habilis and the skull appears thinner with smaller facial bones than H. erectus. Homo erectus: 1.8 million to 33,000 years old. They were much taller (adult males reached 6 feet) and more lightly built than early hominids. Their brains were 50% larger than the earliest forms of Homo. In fact, some H. erectus had brains as large as modern H. sapiens. Between 1.8 and 1.5 mya, H. erectus populations in Africa continued to make and use Olduwan tools. Then around 1.5 mya, they began making more sophisticated tools, called Acheulian tools. Unlike the opportunistically made and discarded Olduwan tools, Acheulian tools were made for specific tasks. A few things about H. erectus distinguish them from the rest of the hominid forms: o First hominid species to occupy Africa as well as other parts of the world, such as: Georgia (in the former USSR), China, Java, and Italy. o First hominid species for which we have evidence of the use of fire: 1.5 mya in Africa and .5 mya in China. o First hominid species for which we have evidence of the use of clothing, such as prepared animal skins, to keep warm in cold climates. o May have built shelters, such as brush piled up as windbreaks. o First hominid species for which we have evidence of the occasional use of caves as shelters (during winters). o First hominid species for which we have evidence of the use of seeds and nuts. Also, they may have cooked (scavenged) meat. 3 Homo antecessor: 780,000 years old at Gran Dolina in Spain, the oldest hominid fossils in Europe. They had an increased brain size and a modern-looking mid-face; otherwise, they resembled H. erectus. They may represent a failed attempt by an early hominid species to colonize Europe. At one of the sites, there is evidence of butchering—cut marks left by stone tools on non-human animal bones as well as human bones! Homo heidelbergensis: 130,000 to 700,000 years old. This species appeared over a geographically wide region (from Africa, through Europe, and into Asia), including: Germany, China, Ethiopia, Greece, Hungary, and Zambia. Many paleoanthropologists believe that H. heidelbergensis were the direct ancestors of both the H. neanderthalensis and modern H. sapiens. While we know very little about their life ways, we know that around 500,000 years ago, they invented a new tool manufacturing technique that allowed them to mass-produce specifically sized and shaped flakes for specific purposes. They had an increased brain size and were the first species for which we have direct evidence of wooden tools: spears and digging sticks. Homo neanderthalensis: 28,000 to 225,000 years old. This species appeared throughout Europe and today’s Middle East, including: Belgium, Croatia, Germany, France, Iraq, Israel, and Italy. They had an increased brain size and particularly short, stocky, and thick bodies. They made and used tools, such as retouched flakes, spears, and digging sticks and were probably the first big game hunting hominids. They are the first hominid species which appeared to have buried their dead and left behind cave art. They may have also had an early form of language. Paleoanthropologists are conflicted about their role in human evolution. One camp sees Neanderthals as brute ape-men who led to an evolutionary dead end and were replaced by modern H. sapiens. The other camp sees them as compassionate and creative early humans who interbred with modern H. sapiens. 4