Stylistics material

advertisement

علم األسلوب

المستوى الخامس

3313 – 3311 الفصل الثاني

STYLISTICS 303 NJD

Level 5

3 credit hours

Instructor Information:

Inaam Perriman, Ph.D.

Office: Room 17/Building 3

11obile:0507155035

iperriman@ksu.edu.sa

http://ksu.edu.sa/inaam

facebook: Inaam PettitnanM'rabet

Office Hours:

Sunday: 12-13

SMS group: 51681 Stylistics

http://sms.ksu.edu.sa

Course Description: .

This course is required for all undergraduate 5th level translation students.

The course includes the factors that determine the choice of the different

words and structures in the different texts, the study of the varieties of

English, the mutual interaction between the topic used, the functions of

style and the different stylistic devices used in the different

types of writing: literary, advertisements, newspaper. lt concludes by

discussing the stylistic problems in translation.

Course objective:

In addition to understanding the basic topics and terminology of stylistics,

this course

should enable you to do the following:

1. Understand the importance of using appropriate words and structures in

the different texts and contexts.

2. Recognize the different stylistic devices used in the different texts.

3. Develop important critical thinking regarding the impact of the choice

of the different words and structures in the different texts.

4. Gain insight into the stylistic problems that you might encounter in the

process of translating.

5. Gain personal insight into the importance of using the appropriate

language for the different texts and contexts.

Course Philosophy:

Research shows that you learn more when you actively process

information, as opposed to passively listen to professor talk. Therefore, my

goal is to keep traditional lecturing to a minimum in this course. We all

use a fair amount of small group work in class. The topics of this work will

then be processed by the whole class. While it is my responsibility to make

the group task meaningful, you will have the responsibility of making the

group process meaningful. It will be helpful to this process if you prepare

before class.

Attendance:

You are expected to come to class and be on time. Regular attendance is

important and a record of attendance will be kept. The university policy is

that once you miss 50%of the class, for any reason, you will be banned of

the course. In fact, from my experience, students who miss 25% of the

classes fail the course anyway!!

Hopefully, you will enjoy the course enough that will be motivated to

attend.

Academic Honesty:

As you might expect, cheating in any form will absolutelgot be tolerated.

If you submit work that is not your own or engage in other forms of cering,

you will receive an F and the administration will be notified.

Course Requirements

Exams:

Two cumulative exams will be given during the term in addition to

quizzes. Each test is cumulative because research shows that we study

differently if we know we will be tested on material again in future. I want

to encourage this type of deep learning. Exams will be composed of

True/False questions, multiple choice questions, short answer questions,

fill in the blanks questions, give example questions and analyze texts to

look for the different stylistic devices.

Grading Procedures

Final course gra cles will b e b asecl on th e f0llowing:

1st In-term 30%

2nd In-term 30%

Final exam 40%

Final grades will b e assessed according to the following scale:

A 90-100

D 60-69

B 80-89

FBelow 60

C 70-79

Tips for Maximum Performance in this Course

1. Keep up with reading.'Each topic contains a lot of new and interesting

information. Trying to cram so much into your memory the night before a

test is not the correct strategy. Instead, read the topics as we go along. This

will help you retain the information as well as make the class discussion

more meaningful.

2. Ask questionsJBy keeping up with the reading you will know what is

confusing or unclear to you. Ask for clarification in class or send an email

or contact me on the chat box on my site.

3.Be an active participant in class and small group discussion. We will do

a lot of both in this course while traditional lecture will be kept to a

minimum. While it is my task to make the discussion topics meaningful

and relevant, it is up to you to be an active class member in order to get the

most out of them.

Course Calendar (modified)

Week 1

Week 2 Style and Stvlistics

Week 3 Introduction to Stylistic Analysis

Week 4 Varieties of English

WeekS Varieties of English

Week 6 Structure, Style

Week 7 Context + exam.

Week 8 Components of Speech events + 1st exam

Vacation

Week 9 Functions of Language

Week 10 Literary Language + Analysis

Week 11 Exercises

Week 12 Language play in advertising

Week 13 Language play in advertising

Week 14 The Language of Newspaper Reports+exam

Week lS The Language of Newspaper Reports

Essential References

-Hough, Graham, Style and Stylistics, Rotlege, 1962.(H.G.808) Ami!

Salman Library.

-Toolan, Michael, Language, Text and Context: essays in Stylistics,

Rotlege,

1992(L.T.40l,4l) Alisha Library.

- Turner, G.W., Stylistics, Penguin, 1973. (T.G.40l) Ami! Salman Library.

- wales , Katie , A Dictionary of Stylistics , ( W.K 418,003) Alisha Library

- http:// www. hud.ac.uk/mh/english/stylistics .

Exam Dates

1st Interm Saturday : ( week 8 )

2nd Interm Saturday : ( week 14 )

Stylistics

Stylistics is the description and antilysis of the variability of linguistic

forms in actual language use . The concepts of "style" and "syulistic"

variation " in language rest on the general assumption that within the

language system , the same content can be encoded in more than one

linguistic form . Operating at all linguistic levels ( e.g. lexicology , syntax

,text linguistics , and inotonation . stylistic variation across texts . These

texts can be literary or nonliterary in nature . Generally speaking , style

may be regarded as a choice of linguistic means , as deviation from a norm

, as recurrence of linguistic forms , and as comparison .

Considering style as choice, there are a multitude of stylistic factors that

lead the language user to prefer certain linguistic forms to others. These

factors can be grouped into two categories: user-bound factors and factors

.referring.to.the ..situation.where.the.Ianguage.is being used. User-bound

factors include, among others, the speaker's or writer's age; gender;

idiosyncratic preferences; and regional and social background. Situationbound stylistic -factors depend on the given communication situation, such

as medium (spoken vs. written); participation in discourse (monologue vs.

dialogue); attitude (level of formality); and field of discourse (e.g.

technical vs. nontechnical fields), With the caveat that such stylistic factors

work simultane-ously and influence each other, the effect of one, and only

one, stylistic factor on language use provides a statistihypothetical

one-dimensional variety. Drawing on this methodological abstraction,

stylistic research has identified many correlations between specific stylistic

factors and language usc. For example, noun phrases

tend to be more complex in written than in spoken lan- gunge in many

speech communities, and passive voice occurs much more frequently in

technical fields ofdis ec'o"urse than in nontechnical ones. Style , as

deviation from a norm , is a concept that is used traditionally in literary

stylistics , regarding literary language as more deviant than nonliterary

language use . This not only pertains to formal structures such as metrics

and rhyme in poems but to unusual lin-guistic preferences in general,

which an author's poet-ic license'allows. Dylan Thomas's poetry, for

example, is characterized by word combinations that are seman-tically

incompatible at first sight and, thus, clearly deviate from what is perceived

as normal (e.g. a grief ago. once below a time). What actually constitutes

the norm' is not always explicit in literary stylistics, since this would

presuppose the analysis of a large collection of nonliterary texts.However ,

in the case of authorship identification, statistical approaches were .

pursued at a relatively early stage. For example, by counting specific

lexical features in the political letters written by an .anonymous Junius in

the 1770s and comparing them with a large collection of texts from the

same period, and with samples taken from other possible contemporary

authors, the Swedish linguist Ellegfird could identify, in the 1960s, the

most likely author of those letters.

The concept of style as recurrence of linguistic forms is closely related to a

probabilistic and statistical understanding of style, which implicitly

underlies the deviation-from-a-norm perspective. It had already been

suggested in the 1960s that by focusing on actu al language use,

stylisticians cannot help describing

only characteristic tendencies that are based on implic- it norms and

undefined statistical experience in, say, given situations and genres. In the

last resort, stylisticfeatures remain f1exible and do not follow rigid rules,

since style is not a matter of grammaticality, but rather of appropriateness.

What is appropriate in a given context can be deduced from the frequency

of linguistic

devices in this specific ·context. As for the analysis of frequencies, corpus

linguistic methods are becoming increasingly important. With the advent

of personal computers, huge storage capacities, and relevant soft- ware,

it is now possible to compile very large collec- tions of texts (corpus

(singular), corpora (plural), which represent a sample of language use in

general, and thus enable exhaustive searches for all kinds of linguistic

,patterns within seconds. This methodology is based on the general

approach of style as probability, by allowing for large-scale statistical

analyses of

text. For example, by using corpora, the notion of text- type-defined by cooccurrences of specific linguistic features-has been introduced to

complement the extralinguistic

concept of 'genre'. The linguistically

defined text types contradict traditionally and nonempirically

established genre distinctions to a considerable extent. In particular, many spoken and written

genres resemble each other linguistically to a far

greater extent in terms of text-types than previously assumed.

Style as comparison puts into perspective a central aspect of the previous

approaches. That is, stylistic analysis always requires an implicit or

explicit comparison of linguistic features between specific texts, or

between a collection of texts and a given norm, In principle,

stylistically relevant features such as style

markers may convey either a local stylistic effect (e.g. an isolated technical

term in everyday communication) or, in the case of recurrence or cooccurrence, a

global stylistic pattern (e.g. specialized vocabulary

and passive voice in scientific texts).

From the multitude of linguistic approaches to

style, two linguistic schools of the twentieth century

have exerted the most decisive influence on the development, terminology,

and the state of the art of sty listics the Prague School and British

Contextual ism. The central dictum of Prague School linguistics, going

back to the Bauhaus School of architecture, is

form follows function. Firmly-established since the 1920s, some of this

dictum's most important proponents are Lubomir Dolezel, Bohuslav

Havranek, Roman Jakobson, and Jan Mukafovsky. These linguists have

paid particular attention to situation-bound

stylistic variation. A standard language is supposed to have a

communicative and an esthetic function that

result in two different 'functional dialects"': prosaic language and poetic

language. More specific function: .

al dialects may, of course, be ident.ified; for example,

the scientific dialect as a subclass of prosaic language,

which is characterized by what is called the 'intellectualization of

language'-lexicon, syntax, and reference conform to the overall

communicative function

that requires exact and abstract statements.

A very important notion is the distinction between

'automatization' and 'foregrounding' in language.

Automatization refers to the common use of linguistic

devices which does not attract particular attention by the language

decoder , for example , the use of discourse

markers ( e.g. well, you know, sort of, kind of) in

spontaneous spoken conversations. with the usual background pattern, or

the norm , in language use it encompasses those

forms and structures that competent language users

expect to be used in a given context of situation.

Foregrounded linguistic devices, on the other hand, are

usually not expected to be" used in a specific context

and are thus considered conspicuous-they catch the

language decoder's attention (e.g. the use of old-fashioned and/or very

formal words such as epicure,

- improvident, and whither in spontaneous spoken

conversations).Foregrounding thus captures deviations :

from the norm. It is obvious that what is considered as

automat zed and foregrounded language use depends

on the communication situation at hand. In technical

fields of discourse, for instance, specialized vocabulary items tend to be

automatized (e.g. lambda marker

in molecular biology), but in everyday communication

become foregrounded devices.

A different, although conceptually similar, tradition

of linguistic stylistics was established by British linguists in the 1930s and

came to be called British

Contextualism, The most important proponents of

British Contextualism include John Rupert Firth,

context in which language ·is used and, secondly, on

characterized by a clear focus, firstly, on the social

M.A.K. Halliday, and John Sinclair. Their work is

the in-depth observation of natural language use. From

the point of View of British Conceptualists, 'linguists

need to describe authentic language use ill context and

should not confine themselves to invented and isolated

sentences. Additionally, linguistics is not considered

as an intuition-based study of abstract systems of form

as, for example, in the merely formal description of

autonomous syntactic rules (as in Chomsky's

approach to language),' but as the observation-based

and empirical analysis of meaning encoded by form.

This approach allows for insights -into the immense

variation within language. It is a fact that depending

on the context of situation, all speakers use different

'registers' (i.e. different styles of language, depending

on the topic, the addressee, and the medium in a given

context of use). Note that there is, of course, a clear

the Prague schools nonon at functional dialect.

Although largely abandoned by mainstream linguists

in the 1960s and 1970s due to the prevailing

Chomsky an school of thought, it had already been

suggested by Firth in the 1950s that large collections

of text were a prerequisite for an empirical approach to stylistic variation.

Thus, it does not come as a tremendous

surprise that, among others, Sinclair set out to

develop computerized corpora that could be used as

empirical databases,

With corpus linguistics now a standard methodology,

stylistic analyses have reached an unprecedented

degree of explanatory adequacy and empirical accuracy.

For example, stylistic features that are beyond most

linguists' scope of intuition, such as the nonstandard

use of question tags in English-speaking teenagers'

'talk, are now feasible in quantitative terms. More

importantly, there is no longer a bias toward foregrounded

phenomena that tend to catch the linguist's

attention. A computer, in contrast, does not distinguish

between conspicuous and common phenomena and

provides an exhaustive array of all kinds of patterns,

depending solely on the search query. Thus, the fuzzy

concept of 'norm' is about to be put on an empiric

footing since the accessible corpus norm represents

the norm of a language as a whole.

Stylistics is a linguistic branch that is immediately

relevant to foreign language teaching. This applies to .

both linguistic and literary stylistics. Language learners

must know which linguistic devices are preferred

by native speakers in specific contexts. Without such a

linguostylistic competence, communication errors

may be made in interacting with native speakers, such

as using highly formal words in informal settings.

Also, learners must have command of text-typological

knowledge, which is important, for example, in writ- ing essays. As for

literary texts, language learners

should acquire a firm understanding of those levels of description where

stylistic variation may occur (e.g.

by analyzing Hemingway's syntactic simplicity and,

moreover, its function). It should be noted that a specific style is

sometimes ascribed.

to a language. In Its entirety, Although the

underling norms remain largely unspecified, general tendencies of stylistic

preference differ across languages, This is particularly important for

translators,

but also for language learners. It is, for instance, common for German

students of English to transfer the .

German style of academic writing, which is characterized by heavy noun

phrases, to their English essays.

As with any other linguistic branch, stylistics is very much a work in

progress, This is because the

object of inquiry constantly grows, evolving new an d specialized fields of

discourse (e.g. genetic engineerstylistic variation come into existence, such as e-mails,

a now widely used genre that seems to blur the traditional

distinction between spoken and written language.

As for empirical approaches to style, new

corpora make it 'possible to address questions of style

not possible before. Also, recent theoretical developments

will no doubt widen the scope of stylistics,

Drawing on British contextualists ' distinction between

language substance (that is, sound waves in the phonic

medium and printed paper in the graphic medium)

and language form (that is, anything that can be transferred

from one medium into the other), it has been

suggested that stylistic analyses should clearly distinguish

between medium-dependent and medium-independent

stylistic variation. Intonation, for example, is

bound to the phonic medium and shows stylistic variation

that cannot be mapped onto punctuation in a

straightforward and monocausal way. With regard to

the graphic substance, English orthography, albeit

highly standardized, is also affected by stylistic variation,

as deliberate misspellings in the language of

advertising and popular culture (e.g. 2 for to/two/too,

lynx, for links) reveal On the other hand, words and

syntax are linguistic devices that, in principle, are subject

to transfer between media, although there are clear

medium dependent preferences of lexical and syntactic choice that need to

be investigated further.

The objective and unbiased approach to stylistic

variation in authentic language use is a cornerstone of

modern descriptive linguistics. Unlike traditional .

grammar, it clearly rejects the normative .prescription

of one specific style.

References

Biber, Douglas. 1989. Variation across speech and writing Cumbridg

:CambridgeUniversity Press.. Coupland, Nikolas (ed.) 1988. Styles of

discourse.London: Croom Helm

Enkvist, Nils Erik-:-1973: Linguistic stylistics; The Haguc

Mouton.

Esser Jurgen. 1993. English linguistic stylistics. Tubingen: Niemeyeer

2000 Medium-transferability and presentation structure in speech and

writing. Journal of Pragmatics 32.

Garvin, PaulL. (ed.) 1964.APrague school readeron esthetics,

literary structure and style. Washington: Georgetown

university Press.

Halliday ,M.A.K 1978 . Language as a Social semiotic the

Social interpretation of language and meaning London

Arnold

Joos, Martin. 1961. The five clocks: a linguistic excursion into

the five styles of English usage. New York Harcourt, Brace

and World

Leeh, geoffrey, and michael Short. 1981. Style In fiction a

linguistic introduction to English fictional prose. London: Longman.

Semino, Elena, and Jonathan Culpeper (eds.) 2002. Cognitive

srylistics: language and cognition in text analysis.

Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Sinclair, John. 1991. Corpus, concordance. collocarion. Oxford:

Oxford Univcrsity Press.

Weber, Jean Jacques (ed.) 1996. The stylistics reader: from

Roman Jakobson to the present. London: Arnold.

JOYBRATO MUK.HERJ8F

See also Firth, John Rupert; Halliday, M.A.K.

(Michael Alexander Kirkwood)

Stylistics

Introduction

He was a little man, considerably less tban .of middle height, and

enormously stout; hehad a large, fleshy face, clean-shaven, with the

cheeks hanging on each side in great dew-laps,and three vast chins;'

his small features were all dissolved in fat; and, but for a crescent of

white hair at the back of his head, he was completely bald: He

reminded you of Mr. Pickwick. He was grotesque, a figure of fun,

and yet, strangely enough, not without dignity, His blue eyes, behind

large gold-rimmed spectaoles, 'were shrewd and vivacious, and there

was a great deal of determination in his face. He was sixty, but his

native vitality triumphed over advancing years, Notwithstanding his

corpulence hlsmovements were quick, and he walked with a heavy

resolute tread as though he sought to impress his weight upon the

earth, He spoke ·in a loud, gruff voice.

PASSAGB A

Name: Frank Ross

Profession :Accountant

Date of Birth : 17.4.49

Place of Birth: Brimingham

Height: 5' 10"

Colour of Hair : Brown

Colour of Eyes : Blue

Question 1 where would you find a sescription of this kind ?

Question 2 Height is given but no weight why ?

Question 3 what kind of information is given in this description ?

Question 4 Which of the details in Passage A would you expect to find in:

(i) An application for a driving licence

(ii) A Health Service registration form .

Which other detailswould yoU expect to find?

Alternatively (or in addintion) one could provoke discussion by a question

of this form: -v ;:

Question 5 In what kinds of official forms would you expect to find

entries like these:

(i) Marital status:

(ii) Address:

(iii) Degrees and qualifications:

(iv) Religion:

Question 6 Who do you think would write a description like that in

Passage A?

PASSAGE B

He' was about six feet tall, thin, and about thirty-five to forty

years old. He had grey eyes and his hair was fair and curly.

He was wearing a dark blue overcoat.

The same sortof questions can be asked as before:

Question 1 Where would you expect to find a descriptionof this kind ?

Question 2 What kind of information is given in this passage?

Question 3 Who do you think would give a description of this kind?

Question 4 What kind of information appears in Passage A which

does not appear in Passage B ? Why?

Question 5 What kind of information appears in Passage B which

does not appear in Passage A? Why?

PASSAGE C

Frank Ross

Mr ROBS has been employed in this firm as clerk for the past

five years. I have always found him reliable and hardworking

and he has the initiative to take on responsibility when required.

He has a cheerful personality and gets on well with his colleagues.

We now proceed to ask the same questionsas before:

Question l Where would you expect to find a description of this kind ?

Question 2 What kind of information is given in this passage?

Question 3 Who do you think would give a description of this kind?

Question 4 How does the information given here differ from that given in

Passages Band C?

Notes on passages A and B

The following conclusion might be expected to emerge, In Passage

A we have details which are both permanent and personal .They are

provided by the person who is being described and who is Consequently

both the author and the object of the description, Passage

B cannot provide information of this land since it is not available

to observation by a third person, Details like date and place of birth

cannot occur in a description of the Passage B type because they

are not ,open to observation and details regarding wearing apparel

are not included in Passage A type descriptions because they relate

only to temporary appearance.

Notes on passages C (A and B)

This passage represents the land of description to be

found in character references, The information relates to the character

of the person described and contains no detail in common with

the descriptions in either Passage A at Passage R This is not because

such information is not available 'to the describer, who is likely to

have noticed a number of physical characteristics of the person

described during the period of his employment, but because such

information is not relevant to the 'person's: capacity for carrying

out his professional work. Here, then, it is the purpose of the

description which control the selection of detail and in this respect

Passage C has a similar function to Passage A. On the other hand

Passage C is the work of one person, and he (or she) is someone

higher in authority or status than the 'person being described. The

information given' is not precise and permanent in an objective sense,

as it is in Passage A, but has the character of a subjective assessment.

From this point of view the accuracy of the description depends on

the sound judgement of the describer rather as the accuracy of the

description in Passage E depends on the perception and memory of

the describer. In one respect, then, Passage C resembles Passage A

and in another respect it resembles Passage B; burin most respects,

of course , it resembles neither.

Now what, it might be asked, has all this to do with the, under.

standing of literary discourse? The answer is that a close analytic

study of these passages brings to the learners' notice features of

conventional ways of describing which (as it has been argued: in

previous chapters) have to be understood as a necessary prelim]

to understanding the nature of literary description such as is

exemplified by the passage from Somerset Maugham cited at the

beginning of the chapter. What the learner will (one hopes) have

come to recognise through an examination of these passages is that

the information which is given depends on such factors as the purpose

for which the description IS made and on the describer's orientation

or point of view In relation to the person (or other object) he is

describing , whether this constrains what he can observe or the

Objectivity of his. observation. In short, he should be able to say that

a certain detail is not included in a certain conventional kind of

description because it 1S irrelevant or because it is inaccessible to the

describer, that this detail is objective and verifiable whereas that detail

is subjective, and so on. With reference to the first, second and third

persons in the communication situation,

we can say that the learner should, have been made aware that the

different kinds of conventional description we have .considered can

be characterised by reference to the relationship between the first

person describer, the second person to whom the description is

directed and the third person object of description. The accessibility.

exactitude and relevance of information can be accounted for in

terms of these relationships.

At this point we can provide the learners with a simple scheme

representing these different relationships:

III

3rd Person

Who/What is

described

I

1st Person

Describer

II

2nd Person

Who receives'

the description

The describer's orientation is, of course, the relationship between I and III

and the purpose of the description is the relationship between I and II.

With this scheme we can now return to the three passages discussed so far

and see how it can be used to characterise them. In this way we can move

from an informal discovery and discussion to a more exact formulation of

the learners' findings.

The kind of description represented by Passage A, for example,

is compiled partly by II and partly by III. The selection of the kind

of detail is made according to what the 2nd Person requires to know

and the provision of particular information is made by the 3rd Person

himself. So there is no separate 1st Person describer, and in Consequence

there is no problem in deciding on purpose since this is absolutely

determined by II acting as I and no problem of orientation since this is

determined by III acting as 1. This might be shown as follows:

I=II

I=III

Name:

Frank Ross

Profession:

Accountant

Date of Birth: 17.4.49

Place of Birth: Birmingham

etc.

In Passage B, of course, the situation is very different. What. I

describes is controlled by his relationship with III-he may have seen

him/her only once, or several time" he/she might be a complete

stranger or someone quite well known. It is also controlled by what

II needs to know, and 'in the case of a witness or Someone giving

evidence, II will typically subject the describer to questioning or

cross-examination so as to elicit the information he wants, so the

situation here is, in this respect, not unlike that in Passage A, except,

of course, that here I and II are distinct. What II needs to know

brings up the relationship between II, and III.

The purpose of a description is to tell somebody something-which

he needs to know. In many cases (though not in the case of Passage

A, and, for reasons just given, often not in the case of Passage :B

either) this involves the describer's judgement as to what is relevant

and what is not. But it also involves him in a decision as t6 what is

already known' by the person to whom his description is directed:

in other words,' the describer, I , assesses the relationship between

II and III. In the case of Passage ,B, II will probably know nothing

at all about III and so requires the information that I gives for the

purposes of Identification, A person, III, exists and I has seen him:

II needs details from I to enable him to identify III when he sees

him. Potentially, then, the relationship between I and III and II and

III can be the same; though operating, .as it were, in' a reverse

direction. We might represent this in a simple diagram as follows:

PASSAGE B

The dotted line here represents the matching procedure which leads

to identification .

The diagram for Passage A will be different since essentially all

that happens is that information passes from III to II directly after

II has specified which information is required. We might show this as

follows:

PASSAGE A

Here the dotted line indicates that I is a compound of III and II and does

not exist as a separate entity.

Passage C resembles Passage B in that II can relate I's information

to III. But this is not done for the purposes of identification but in

order to arrive at a judgement of qualifications, suitability and so

on and II will compare I's description with information deriving

from other sources such as an application form (usually a Passage A

type description) and his own experience of the person in interview.

Another difference is that there, will be no prompting from II to I

as there is in Passage B. We might express these facts by removing

the parenthesis around III and showing only a single arrow from

I to II

PASSAGE C

A stylistic analysis of passage D ( The literary passage )

Having prepared the ground, then, we can now present the literary

passage as PASSAGE D and proceed to investigate In what respects

it differs from the others. We may begin with the same first question

as before:

Question 1 Where would you expect to find a description of this kind?

Question la Would this description be given by a witness, like the

description in Passage B?

Question 1b Would this description appear in a reference, like the

description in Passage C?

Question 2 What kind of information is given in this passage?

Question 3 How does the information given in this passage differ

from that given in Passage A, Passage B, Passage C?

Question 2a What is the difference between these descriptive details:

He was shrewd

He was sixty

He was a little man

Question 3a In which of three passages you have already

examined would you expect to find details of the following kind

He was shrewd

He was sixty

He was a little man

Question 3b Why do you think it would be strange to find the

following descriptive details in the passages mentioned:

He was shrewd: in passage A

He was sixty: in Passage B

He was a little man: in Passage C

Question 4 Draw a simple diagram like those given for the previous

passages to show the relationship between I, II and III

in this passage.

Question 5 Write brief descriptions of a conventional kind based on

Passages A, B, rind C using 'as much information given

in Passage D as possible but providing more exact

information when required.

Question 6 Write down the expressions in Passage D and in your

A-type and B-type descriptions which refer to the size

of the person described. .

Question 7 What is the difference between the words in Column I

and the words in Column II?

I

small

little

large

II

tiny

minute

vast

enormous

great

Question 8 What kind of words are used to describe the man's size in this

passage 7

Question 9 How is the selection of marked subjective words related

to the absence of a real III as shown in the diagram drawn in answer to

Question 4 ?

Varieties of English

To use language properly, we of course have to know the

grammatical structures of language and their meanings. But

we also have to know what forms of language are

appropriate for given situations.

The Common Core

Many of the features of English are found in all, or nearly all

varieties. We say the general features of this kind belong to

the 'common core' of the language. Take for instance, the

three words children, offspring and kids. Children is a

'common core' term; kids is informal and familiar. It is

safest, when in doubt, to use the 'common core' term; thus

children is the word to use more often. It is part of 'knowing

English' is knowing in what circumstances it would be

possible to use offspring or kids instead children. Below is

another illustration, this time from grammar:

1) Feeling tired, John went to bed.

2) John went to bed early because he felt tired.

3) John felt tired, so he went to bed early.

Sentence (2) is a 'common core' construction. It could be

used in both speech and writing.( 1) is rather formal in

construction, typical of written exposition; (3) is informal,

and likely to occur in relaxed conversation.

Speaking versus Writing

Josef Essberger

The purpose of all language is to communicate - that is, to move

thoughts or information from one person to another person.

There are always at least two people in any communication. To

communicate, one person must put something "out" and another

person must take something "in". We call this "output" (>>>)

and "input" (<<<).

• I speak to you (OUTPUT: my thoughts go OUT of my

head).

• You listen to me (INPUT: my thoughts go INto your head).

• You write to -me (OUTPUT: your thoughts go OUT of your

head).

• I read your words (INPUT: your thoughts go INto my

head).

So language consists of four "skills": two for output (speaking

and writing); and two for input (listening and reading. We can

say this another way - two of the skills are for "spoken"

communication and two of the skills are for "written"

communication:

Spoken:

>>> Speaking - mouth

<<< Listening - ear

-Written:

>>> Writing - hand

<<< Reading - eye

What are the differences between Spoken and Written English?

Are there advantages and disadvantages for each form of

communication?

Status

When we learn our own (native) language, learning to speak

comes before learning to write. In fact, we learn to speak almost

automatically. It is natural. But somebody must teach us to

write. It is not natural. In one sense, speaking is the "real"

language and writing is only a representation of speaking.

However, for centuries, people have regarded writing as superior

to speaking. It has a higher "status". This is perhaps because in

the past almost everybody could speak but only a few people

could write. But as we shall see, modern influences are changing

the relative status of speaking and writing.

Differences in Structure and Style

We usually write with correct grammar and in 'a structured way.

We organize what we write into sentences and paragraphs. We

do not usually use contractions in writing (though if we want to

appear very friendly, then we do sometimes use contractions in

writing because this is more like speaking.) We use more formal

vocabulary in writing (for example, we might write "the car

exploded" but say lithe car blew up") and we do not usually use

slang. In writing, we must use punctuation marks like commas

and question marks (as a symbolic way of representing things

like pauses or tone of voice in speaking).

We usually speak in a much less formal, less structured way. We

do not always use full sentences and correct grammar. The

vocabulary that we use is more familiar and may Include slang.

We usually speak in a spontaneous way, without preparation, so

we have to make up what we say as we go. This means that we

often repeat ourselves or go off the subject. However, when we

speak, other aspects are present that are not present in writing,

such as facial expression or tone of voice. This means that we.

can communicate at several levels, not only with words.

Durability

One important difference between speaking and writing is that

writing is usually more durable or permanent. When we speak,

our words live for a few moments. When we write, our words

may live for years or even centuries. This is why writing is

usually used to provide a record of events, for example a

business agreement or transaction.

Speaker & Listener I Writer & Reader

When we speak, we usually need to be in the same place and

time as the other person. Despite this restriction, speaking does

have the advantage that the speaker receives instant feedback

from the listener. The speaker can probably see immediately if

the listener is bored or does not understand something, and can

then modify what he or she is saying.

When we write, our words are usually read by another person in

a different place and at a different time. Indeed, they can be

read by many other people, anywhere and at any time. And the

people reading our words, can do so at their leisure, slowly or

fast. They can re-read what we write, too. But the writer cannot

receive immediate feedback and cannot (easily) change what has

been written.

How Speaking and Writing Influence Each

Other

In the past, only a small number of people could write, but

almost everybody could speak, Because their words were not

widely recorded, there were many variations in the way they

spoke, with different vocabulary and dialects in different regions.

Today, almost everybody can speak and write. Because writing is

recorded and more permanent, this has influenced the way that

people speak, so that many regional dialects and words have

disappeared. (It may seem that there are already too many

differences that have to be learned, but without writing there

would be far more differences, even between, for example,

British and American English.) So writing has had an important

influence on speaking. But speaking can also influence writing.

For example, most new words enter a language through

speaking. Some of them do not live long. If you begin to see

these words in writing it usually means that they have become

"real words" within the language and have a certain amount of

permanence.

Influence of New Technology

Modern inventions such as sound recording, telephone, radio,

television, fax or email have made or are making an important

impact on both speaking and writing. To some extent, the

divisions between speaking and writing are becoming blurred.

Emails are often written in a much less formal way than is usual

in writing. With voice recording, for example, it has for a long

time been possible to speak to somebody who is not in the same

place or time as you (even though this is a one-way

communication: we can speak or listen, but not interact). With

the telephone and radiotelephone, however, it became possible

for two people to carry on a conversation while not being in the

same place. Today, the distinctions are increasingly vague, so

that we may have, for example, a live television broadcast with a

mixture of recordings, telephone calls, incoming faxes and emails

and so on. One effect of this new technology and the modern

universality of writing has been to raise the status of speaking.

Politicians who cannot organize their thoughts and speak well on

television win very few votes.

English Checker

• aspect: a particular part or feature of something

• dialect: a form of a language used in a specific region

• formal: following a set of rules; structured; official

• status: level or rank in a society

• spontaneous: not planned; unprepared

• structured: organized; systematic

Note: instead of "spoken", some people say "oral" (relating to

the mouth) or "aural" (relating to the ear).

© 2001 Josef Essberger

FORMAL 8: INFORMAL ENGLISH

Summary

Language Styles

Rules of Language Styles

Different Styles between Informal & Formal English

Dictionary of Formal & Informal English

Exercise 1

Exercise 2

2

3

4

6

7

7

Language Styles

There are three main language styles:

1. Formal

2. Semi-Formal

3. Informal

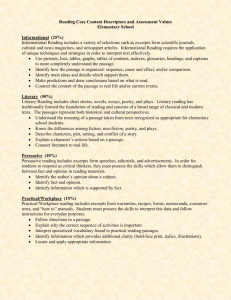

The diagram below illustrates how these styles are rated on a scale of 0 to 10.

Diagram of Formal & Informal English

Rules of Language Styles

The following rules apply to both written and spoken English.

analysis

Language Style: Rules

Writing to ….

Company

Know name of recipient?

No

Formal

Dear Sir or Madam,

Yes

Formal

Dear Sir,

Person

Have spoken or exchanged info?

No , Yes

Are on familiar terms?

No

Semi-formal

Dear Mr. Donald,

Yes

Informal

Dear Guy

Don't know anything about the person who receives letter.

Know title or name of person. Never met or exchanged info.

Know name of person and have exchanged . greetings.

Know person well and on familiar terms.

Different Styles between Informal & Formal English

The follow examples illustrate the main differences between informal and

formal English.

1. Active & Passive Voice

Our technician repaired the fault on 12th June. Now it's your turn to pay

us. Informal

Although the fault was repaired on 12th June, payment for this

intervention has still not been received. Formal

2. Verb Form: Phrasal Verbs & Latinate

The company laid him off because he didn't work much. Informal

His insufficient production conducted to his dismissal. Formal

3. Language: Direct & Formulaic

I'm sorry but ...

I'm happy to say that ... Inforaml

We regret to inform you that ...

We have pleasure in announcing that ... Formal

4. Use of Slang

He had to get some money out of Clhole in the wall ... Informal

He withdrew the amount from an ATM. Formal

5. Personal Form & Nominators

If you lose it, then please contact us as soon as possible. Informal

Any loss of this document should be reported immediately ... Formal

6. Linking Words

The bank can't nnd the payment you say you've made. Informal

Notwithstanding that the payment has been sent the bank fails to

acknowledge it. Formal

7. Revitalised Sentences

Anybody or ,my company . Informal

... any natural person who, and any legal entity which …. Formal

8. Modal Usage

If you need any help give us a call . Informal

Should you require any assistance, please feel free to contact us ... Formal

9. Singular & Plural Person

I can help you to solve this problem. Call me! Informal

We can assist in the resolution of this matter.

Contact us on our toll-free number. Formal

Dictionary of Formal & Informal English

Type Informal

Prep. About ...

Idiom Agree with ...

Conj. And

Idiom Bearing in mind

Conj. Because ...

Verb Begin

Conj. But

Adj. Careful/Cautious

Verb Carry out

Verb Check

Adj. Enough

Verb Fill me in

Verb Find out

Verb Follow

Verb Get

Verb Get in touch

Verb Go over

Verb Has to be

Verb Have to give

Conj. If ...

Conj. If ... or not.

Idiom If you don't ...

Idiom If you've got any questions ...

Idiom In accordance with ...

Idiom In the red

Verb Involve

Idiom Lost

Verb Make sure

Adj. Many

Verb Order

Verb Pay·

Idiom Put in writing

Idiom Sorry!

Verb Supply

Verb Take away

Verb Tell

Verb Trusted

Idiom We don't want to do this ...

Idiom We'll call the law ...

Idiom When we get ...

Idiom Whenever we like '"

Verb Write (e.g. Cheque)

Verb Written

Formal

Regarding / Concerning ...

Be bound by ...

As well as ...

Reference being made to ...

As a result of / due to (the fact) ...

Commence

While / Whereas

Prudential

Effect

Verify

Sufficient

Inform / Tell

Ascertain

Duly observe

Receive

Contact

Exceed

Shall be

Submit

Should ...

Whether ... or not.

Failing / Failure to...

Should you have any queries ...

Pursuant to

Overdrawn

Entail

Inadvertently mislaid

Ensure

Several/Numerous

Authorise

Settle

Provide written confirmation

We.regret ...

Furnish

Withdraw

Disclose

Entrusted

This a course of action we are anxious to avoid ...

We will have no alternative but involving our legal ...

On receipt

Without prior notice ...

Issue (e.g. Cheque)

Shown / Indicated

Summary of Differences between Formal & Informal English

Informal

1. Active Voice

2. Phrasal Verbs

3. Direct Language

4. Possible use of Slang

5. Personal Form

6. Little use of Conjunctions

7. Few Revitalised Sentences

8. Direct Style

9. 1st Person Singular

Formal

Passive Voice

Latinate Verbs

Formulaic Language

No use of Slang

Nominator

Linking Words

Revitalised Sentences

Modal Usage

1st Person Plural

Formal Ianguage

When writing or speaking, we choose the words which seem most suitable

to the purpose and audience. In academic writing we use formal language,

avoiding the use of slang and colloquial language.

Try to learn a range of appropriate language for expressing your opinions

and referring to those of others.

Some of the Ianouaqe in the following examples is more appropriate for

speakinq than writinq. Identify which expressions are too informal.

1. When I look at the situation in emergency wards, with many staff

leaving, it's hard not to worry about how many doctors will be available to

treat patients in the future.

2. If we consider the situation in emergency wards, with increasingly low

staff retention rates, there are concerns about thecapacity of hospitals to

maintain adequate doctor to patient ratios.

3. It's so obvious that people were given jobs just because they were male

or female. I don't think that is an acceptable approach and is even against

the law.

4. It appears that in a number of instances jobs were assigned on the basis

of gender. Given the current anti-discrimination laws, this raises serious

concerns.

In contrast to spoken English, a distinctive feature of academic writing

style is for writers to choose the more formal alternative when selecting a

verb, noun, or other part of speech.

English often has two (or more) choices to express an action or

occurrence. The choice is often between, on the one hand, a verb which is

part of a phrase (often verb + preposition), and a verb which is one word

only. Often in lectures and in everyday spoken English, the verb +

preposition is used (eg speak up, give up, write down); however, for

written academic style, the preferred choice is a single verb wherever

possible.

For example

Informal: The social worker looked at the client's history to find out which

interventions had previously been implemented.

Academic: The social worker examined the client's history to establish

which interventions had previously been implemented.

Exercise 1

Rewrite the sentences in a more academic style using verbs from the list

below.

Note that you may need to change the verb tense.

• investigate

• assist

• raise

• discover

• establish

• increase

• eliminate

1. Systems analysts can

managers in many different ways.

2. This program was

to improve access to medical care.

3. Medical research expenditure has to nearly $350 million.

4. Researchers have

that this drug has serious side effects.

5. Exercise alone will not medical problems related to blood pressure.

6. Researchers have been this problem for 15 years now.

7. This issue was

during the coroner's inquest.

Personal or impersonal style ?

Should you use a personal or impersonal style? Until quite recently, text

books on scientific writing advised students to use an impersonal style of

writing rather than a personal style.

An impersonal style uses:

• the passive voice

• the third person rather than the first person ( it rather than I or we)

• things rather than people as subjects of sentences.

However, overuse of the passive voice may mean that your writing is less

precise,and it may lead to writing which is more difficult to read because it

is less natural than the active voice.

Times are changing, and in some disciplines and sub-disciplines of

Science it is now quite acceptable to use the active voice, personal

pronouns such as I and we, and to use people as subjects of sentences.

Examples of active and passive sentences

Active: I observed the angle to be ...

Passive: The angle was observed to be ...

Active: The authors suggest. ..

Passive: It is suggested ...

Active: We used a standard graphical representation to ...

Passive: A standard graphical representation was used to ...

Examples of thefirst and third person pronouns

First person: I found ...

Third person: It was found that. ..

First person: I assumed that ...

Third person: It was assumed that...

Examples of persons or things as subjects

Person as subject: I noticed...

Thing as subject: Analysis of the raw data indicated...

Person as subject: In this report I show...

Thing as subject : This report presents Impersonal style

Compare the changes in these sentences from informal to academic style

Informal writing

When I look at the situation in emergency

wards, with many staff leaving, it's hard

not to worry about how many doctors will

be available to treat patients in the future.

It's so obvious that people were given

jobs just because they were male or

female. I don't think that is an acceptable

approach and is even against the law.

Academic writing

If we consider the situation in emergency

wards, with increasingly low staff

retention rates, there are concerns about

the capacity of hospitals to maintain

adequate doctor to patient ratios.

It appears that in a number of instances

jobs were assigned on the basis of

gender. Given the current antidiscrimination

laws, this raises serious

concerns.

You will notice that, in general, in academic writing we:

• minimise the use of the personalf in the text: avoid writing

'When flook; f don't think this is an acceptable approach'

• use formal verbs, and fewer verb phrases (verb + preposition),

use consjder rathet than look at

• use impersonal expressions: there are.. , this raises

• use more nouns than verbs: concerns, rather than to worry

• avoid emotional expressions, such as it's so obvious ( it appears is

preferable); justbecause ( assigned on the basis of is preferable)

• aim for concise, often abstract expression, gender, rather than male or

female.

Objective writing

• In general, academic writing aims to be objective in its expression of

ideas. Therefore specific reference to personal opinions, or to yourself as

the performer of actions, is usually avoided.

Expressing opinions

Personal

In my opinion

I believe that. ..

In my view ...

'Objective'

It has been argued that

Some writers claim...

Clearly, ...

It is clear that...

There is little doubt that..

Avoiding too much reference to yourself as agent in your writing

Agent or performer No agent or performer

I undertook the study... The study was undertaken...

I propose to …. It is proposed to ….

In this essay I will examine... This essay examines...

Structure, Style and Context

1.0 Objectives

This book is a short introduction to a large topic: how the structures

of language serve the communicative needs of man. Our communicative

needs span the whole range of our experience, from buying bus

tickets to making love or war. Language, to serve these needs, must

have a similar range, and any natural language, be it English or

Eskimo, is a system of great complexity.

The complex structures of language, however, appear to be built

up with remarkable economy from a limited set of units and processes.

Language, in the words of Van Humboldt, makes infinite

use 'of finite means. Our main focus, then, will be on some of the

basic units and processes of the 'structure' or perhaps better the

'construction' of English.

What we say or write, however, is seldom built, as it were, 'into

the air'. We adapt our English to particular purposes and people,

even from a very early age. Consider the following dialogue between

a rather smallchild and its mother, overheard in a supermarket:

(1) CHILD: Mummy, buy these. [Pointing to a pink box of icecream

cones]

MOTHER: No, not those. [Moving on]

CHTLD: You can, you know, it's your own choice.

'It's your own choice' happens to be true, up to a certain point,

of language as well as of shopping, A language, like a supermarket,

provides its users with a remarkable range of options, some indispensable,

others not. Much of what follows will focus on these.

One particular kind of option is illustrated in the child's two remarks

to its mother. The simple appeal, 'Mummy buy these' contrasts

with the statement 'You can, you know, it's your own choice'.

The latter has a distinctly more adult look; it still functions as an

appeal, but in what seems like a much more sophisticated way.

Between the first remark and the second, the child has switched

styles. Its purpose remains, presumably, the same, but the langnqge

shows a surprising re-adaptation after the mother's 'No, not those'.

A 'style' can be regarded as an adaptation of language to a particular

purpose or audience: adaptations of this kind will be a major theme

of our text.

This wilI involve taking a fresh look at processes of which we ourselves

have been part ever since we started to talk. There is, of course,

some difficulty in achieving a new focus upon what we have regularly

taken for granted since early childhood. As Chomsky (1968) phrased

it in Language and Mind:

Phenomena can be so familiar that we do not see them at all,

important as they may be to our social or personal lives.

1.1 Structure

At tills point, a brief initial illustration of what we mean by a 'structure'

and by the options surrounding it, may be in order. Take the

instruction regularly flashed to aircraft passengers:

(2) FASTEN SEAT BELTS

That this is structured becomes clear as soon as we scramble the

words. It begins to lose shape and its function becomes unclear if

we remake it as

(3) *SEAT BELTS FASTEN

and both shape and function disappear in

(4) *SEAT FASTEN BELTS.

Neither (3) nor (4) is quite 'English'. (4) is more or less what Jacobs

and Rosenbaum (1967) appropriately call 'word-salad'. (An asterisk

* at the beginning of a sequence will mean 'This isn't English' or in

more general terms 'Tills isn't right'.)

FASTEN SEAT BELTS, however, is recognizably English. It has

one of the typical forms of an English imperative, which we can write

informally as:

(5) V NP

i.e. a VERB (V), here fasten, followed by a NOUN PHRASE (NP),

here seat belts. It is easy to make up approximately parallel structures

e.g.

(6) Shut your window

(7) Make fresh tea

and all of these will have a common element of meaning which we

can conveniently call DIRECTIVE or 'command '.

[One must add, however,· that all imperatives are not shaped

exactly like (2). There are one-word imperatives, consisting of a

single verb, e.g. 'Stop!' and more complex imperatives like 'Tell

Daddy supper won't be ready till eight'. And the 'hidden' structure

of imperatives, which we shall be presenting later, is rather more

complex than the crude formula 'V NP' might suggest.]

Here our point is simply that FASTEN SEAT BELTS is immediately

recognizable as an English imperative, partly because it

parallels similar imperatives like (6) and (7) and partly because it

contrasts with non-imperatives like

(8) The passengers fastened their seat belts

which do not fit the imperative pattern. These two principles of

parallelism or analogy between structures of similar meaning and of

contrast between structures of dissimilar meaning, are basic to the

workings of language:

Lewis Carroll was perhaps one of the first to grasp that structures

can be meaningful in themselves. Consider his famousstanza from

Jabberwock y;

(9) 'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe

All mimsy were the borogroves

And the mome raths outgrabe.

This is interpretable up to a point even without the word-meanings

later supplied by Humpty Dumpty. Vie can infer, for instance that

in the world of Jabberwocky toves can be slithy and may gyre; that

some raths are mome. some borogroves mimsy and so on.

Here of course we are responding to structural signals rather than

to word-meanings as such. The slithy toves, for instance, has apparently

one of the characteristic shapes of an English noun phrase

(The plus Adjective plus Noun) and we recognize gyre and gimble

as verbs because they pattern with the auxiliary verb did. Compare:

(10) a) Did gyre and gimble

b) Did swill and guzzle ...

Structural meanings, one might say, are thus up to a point independent of

word-meanings: structures, at any rate, as well as words, can .

in themselves be meaningful.

1.2 Style

A style is a way of doing something. Thus one might speak of a

Japanese style of flower arrangement, Muhammad Ali's style of

boxing or Shakespeare 's style of writing.

Implicit in this view of style is some kind of distinction between

what is done and how (Epstein 1978) as in

(11) WHAT

Flower-arrangement

HOW

a) Japanese-style

b) Classical Seika

c) As executed by Rikun Oishi

The entries in (11) are intended to suggest simply that one can speak

of a style in terms descending from the general to the particular: e.g.

merely as Japanese, or within Japanese flower-arrangements generally,

of the classical 'Seika ' school or within that school of the

work of one particular master, Rikun Oishi. There is thus a strong

association of the concept 'style' both with particular groups of

stylists (e.g. the English Metaphysical or Augustan poets) and within

any given group, with its outstandingly representative individuals,

e.g. Donne or Pope.

Styles, of course, are not peculiar to the fine arts or to the great.

There are styles, e.g. of baking bread, playing rugby or newspaper

reporting and one might well say of a party that it was in the best

Corworst) style of its hostess.

We shall not at this stage involve ourselves with the individualizing

properties of styles - these will be touched upon later - but rather

with the close relationship of styles to structures and the rather

intractable problem of distinguishing the what of a style from the

how.

As a first example take two closely related sentences:

(12) a) Victoria spoiled the puddings

b) The puddings were spoiled by Victoria.

For these the content is virtually identical: (b) is simply the PASSIVE

form of (a), and (a) can be converted into (b) by a simple linguistic

move, the Passive Transformation, which will be presented later.

The difference between (a).and (b) is thus largely stylistic: they are

very nearly identical on the what,differing mainly on the how. There

are evident structural differences, though we shall later see·that the

underlying structures for both sentences - their 'inner' as opposed

to their surface forms - are remarkably alike.

The surface difference is largely one of focus. In one situation

there may be a good reason for starting the sentence with Victoria,

as in (a); in another situation, the puddings, as in (b), may rate first

place.

(There are a few 'trick' sentences, e.g. All hunters chase some foxes,

for which passive and non-passive versions mean, or may mean,

different things, but these need not detain us.)

As another example of differences which can be regarded as

mainly stylistic, take three translations of a verse of the Book of

Ecc1esiastestEcclesiastes 12.1):

(13) a) Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth

(Authorized Version, 1611).

b) Remember also thy Creator in the days of thy youth

(Revised Version. 1881).

c) So remember your Creator while you are still young

(Good News Bible, 1976).

All three of these consist basically of an imperative - e.g. 'Remember

your Creator'. and an indicator of time, e.g. 'while you are still

young. In (a) and (b), this time-indicator or 'adverbial of time' is

structured as a prepositional phrase: 'in the days of thy youth'.

In (c) it is structured as a clause: 'while you are still young'. The

conversion is basically from a structure whose nucleus is the nounphrase

the days of thy youth, to one in which the nucleus is a sentence,

you are stiR! young, The change involves the loss of the noun

days which is concrete and 'imaginable' by comparison with the

perhaps more abstract 'while.' of (c).

(Again the technical concepts of 'clause', 'prepositional phrase'

etc. will be explained later: the simple issue is that the change of

style involves a change of structure.)

There is, of course, a less simple issue, namely that the changes of

style involve changes of content too. The days of (a) and (b) have

fallen away in (c). There is also the change from thy to your. Thy,

for the modern reader, has formal and archaic overtones which the

translators of the modern Good News Bible are avoiding. Thy,

incidentally,

is a 'singular' form, whereas your is either singular or

plural, so that the focus of (a) and (b) on a single person is diffused

in (c).

There is also the important contrast between now, also and SO.

The nOW of (a) anticipates and therefore reinforces the time-adverbial

in the days of thy youth, with a special note of immediacy. Also in (b)

marks the sentence as part of a sequence, but without suggesting·

any particular way in which it links up with what has gone before.

So in (c) is also a connective, but implies a causal connection with the

preceding sentence: the actual sequence in tile Good News Bible is

(14)You aren't going to be young very long.

So remember your Creator in the days of your

youth, before those dismal days and years

come when you will say 'Idon't enjoy life'.

The point of our discussion of (13) is to illustrate that what wesay

is usually affected by how we say it, in other words that we cannot

make an absolute separation between content and style As a more

extreme example, conslder these two exchanges, between, say, an

anny officer (O) and a trainee (T):

(15) a) O: Your hairs a bloody disgrace.

T: Yes sir.

b) O: Report at once to the barber.

T: Yes sir.

In both cases O 's remark may have exactly the same effect: T gets

his hair cut as soon as possible. Both 'O' remarks can thus be roughly

interpreted as 'Get your hair cut'. But they have in fact not a single

word in common and they differ structurally too: the (a) remark is a

statement, the (b) one an imperative.

A further consideration is that the two exchanges of (15) may

reflect quite different situations: there are cases in which Your hairs

a bloody disgrace will not take effect as an instruction, and there are

cases in which Report at once to the barber may be addressed to a

man whose hair is by no means disgracefully long. So that with 15(a)

and 15(b) we have reached a point at which there are differences of

structure, of style, and potentially, of situation too.

This brings us to another and rather different use of the word

style. Compare the following:

(16) Beat till smooth

(17) LAKE MURDER PROBE. DRAMA

(18) Subject to the approval of the Board of the Faculty of Arts,

a candidate may present himself for examination and obtain

credit in not more than two courses additional to those prescribed

in paragraph A 27 above

(19) When your real hair won't do, Dynel will.

We mightwellsay thathere .we have four different styles: .(16) Iooks

like a snippet from a cookery-book, (17) is recognizably a newspaper

headline, (18) a university regulation and (19) from an advertisment.

But these four sentences differ basically not only in style but in

content too: they reflect, to put it briefly, four different ways of

writing adapted to four very different kinds of purpose. We often

use 'style' in this sense when we speak , say , of a legal versus a scientific

style, or of a 'novelistic' style versus a strictly historical one.

Here we have arrived at a second and sometimes rather useful

concept of .style, namely that it is the adaptation of language to particular

purposes or occasions, e.g. of (16) to 'the cookery-book

situation', and so on. Thus the headline

(17) LAKE MURDER PROBE DRAMA

shows a particular adaptation of English (sometimes called 'block

language ') to the purposes of newspaper headlining. (17) could perhaps

be roughly paraphrased as 'There's a fuss (DRAMA) about the

investigation (PROBE) into the MURDER at the LAKE.' Other

interpretations, of course, are possible. The point of interest, however,

is that the paraphrase is substantially longer than the original,

which consists simply of four nouns without any connective words

at all. The headline achieves its brevity by structuring of a particular

kind (,premodification ') which is best shown in a diagram:

(18)

LAKE

MURDER

PROBE

DRAMA

Here LAKE 'nodifies' MURDER, forming the subordinate unit

LAKE MURDER: this as a whole 'modifies' PROBE to form the

unit LAKE MURDER PROBE, which again acts as a modifier

to the 'headword' DRAMA.

The hierarchical organization of (18) into a 'branching tree'

structure as we shall see, is typical of language organization generally.

What is much less typical of 'ordinary' English is an unbroken

sequence of four nouns, though patterns like that of (17) are fairly

common in certain styles, notably those of newspaper headlines

and of certain kinds of advertising copy: compare 'million-dollar

.machine tools' or 'Philips PABX systems technology. '

[Our analysis of Lake as a 'noun' in a structure like Lake Murder

will be justified later.]

1.3 Style and Vocabulary: Lexical Sets

Up to this point our focus has been on the dependence of style on

structure. In fact, as we shall show later, language can be seen as

'structured' at three rather different levels: those roughly speaking

of sentence, word and sound. Each of these three levels must be

explored if we are !o understand the workings of language or to

attempt a full stylistic analysis of a given text. At this point, however,

a brief note on one particular aspect of the relationship of style to

vocabulary may be in order. Take the following recipe:

(19) CHOCOLATE SAUCE

250 ml brown sugar

45 ml cocoa

1 ml cream of tartar

125 ml water

15 ml butter

5 ml vanilla essence

Mix sugar with cocoa and cream of tartar in a saucepan ...Add

water and mix to a paste. Melt and cook for five min over

low heat. Remove from heat, add butter and cool slightly.

Stir in vanilla and serve hot.

Here we have typical structures: the noun phrases listing ingredients

(e.g. 45 ml cocoa) and the brief imperatives (Stir in vanilla

and serve hot) telling us what to do with them. But we have also a

conspicuous set of words characteristic of cookery books: the names

of ingredients - sugar, cocoa, water, butter etc. - and the words of

instruction - mix, add, melt, cook, stir. But though the names are

nouns and the instructions are verbs, both 'belong' to the same art,

namely cookery.

Together they constitute a LEXICAL SET, which we can define

informally as

a group of words relating to a particular field of experience.

This of course is a somewhat flexible notion: just as it is difficult in

practice to say where one field of experience ends and another

begins, so it is with lexical sets. Perhaps the simplest example of a

lexical set is a shopping list:

(20) Pilchards; matches, bread, pencil, light-globes, potatoes ...

and the open-endedness of shopping lists (one could so easily add 'Fetch children at 1230' -) parallels the elasticity of lexical sets: there

is no operational test for membership of any given set.

But since the effect of a text is partly determined by the vocabulary,

lexical sets are often worth looking for. Here, for instance, is the

first stanza of Ben Johnsons 'Song to Celia' (1616) in which we

retain the Elizabethan spelling:

(21) Drinke to me, onely, with thine eyes,

And I will pledge with mine;

Or Ieaue a kiss but in the cup,

And ne not looke for wine.

The thirst, that from the soule doth rise,

Doth aske a drinke diuine:

But might I of lOVE'S Nectar sup,

I would not change for thine.

Here again, some of the words 'hang together' - Drinke, pledge,

CUlP, wine, thirst, nectar and S~JPl- and again some are nouns and some

are verbs. Together, however, they 'sustain' the concepts of thirst,

drinking and their significance in the context of love, focussed in the

word of commitment, pledge.

But the sam.ewords.in a different structural setting, will of course

register in a very different way: 'Mr Jonson liked to drink at the

Mermaid and pledge Doll Tearsheet in 3. cup of wine; "Dolly", he'd

say, "you're the nectar that I'd like to sup".' This fails of the stylistic

effect of (21), though we have of course altered vocabulary as

well as structures.

1.4 Utterances and Texts

At this point it will be useful to introduce a rather neutral term for

'something said': the term UTTERANCE.

Utterances vary considerably in length, complexity and structure.

'Yuk', says a child, recoiling before a spoonful of medicine. This

is a very short utterance. At the other end of the scale are lengthy

sequences such as a news broadcast. or a sermon.

An utterance can be roughly defined as 'any stretch of talk, by one person,

before arid after which there is silence on the part of that

person' (Harris, cit. Lyons: 1968).

The written counterpart of an utterance is a TEXT, which we can

r crudely define, following Harris, as 'a stretch of writing with a

beginning and an end". Texts, like utterances, may be very short

(e.g. a NO PARKING notice) or very long (e.g. Milton's Paradise

Lost). An utterance can be converted into a text simply by writing

it down, and in linguistics and anthropology the term text is often

used for transcripts or recordings of unscripted speech.

1.5 Ear-Language and Eye-Language

There are however, substantial differences between the organization

of language for speech on the one hand, and for writing on the other,

so that 'ear-language' and 'eye-language' are often clearly distinguishable.

Consider first:

(22) Any person who, not being a Post Office employee, enters

this room without the permission of the Postmaster-General

will be prosecuted in terms of Section l00(i) of the Post

Office Act, No. 44 of 1958.

Tills is a notice of a kind often seen in offices where civil service

styles of English prevail, but it is difficult to imagine its being spoken